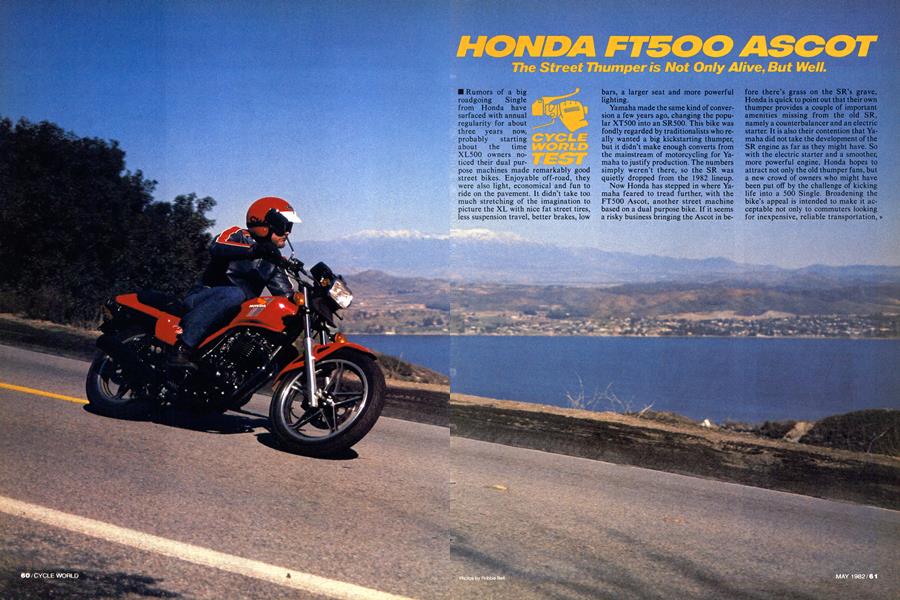

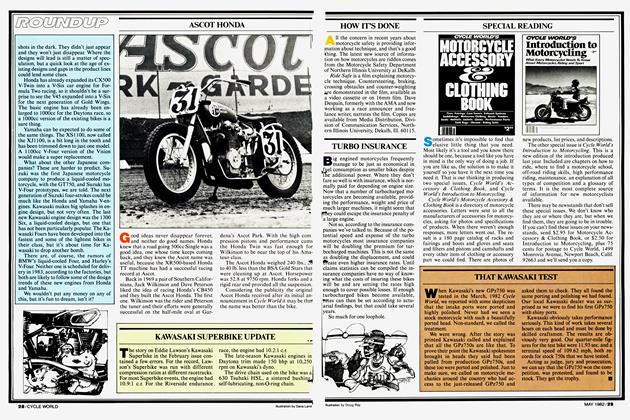

HONDA FT500 ASCOT

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Street Thumper is Not Only Alive, But Well.

Rumors of a big roadgoing Single from Honda have surfaced with annual regularity for about three years now, probably starting about the time XL500 owners noticed their dual purpose machines made remarkably good street bikes. Enjoyable off-road, they were also light, economical and fun to ride on the pavement. It didn't take too much stretching of the imagination to picture the XL with nice fat street tires, less suspension travel, better brakes, low

bars, a larger seat and more powerful lighting.

Yamaha made the same kind of conversion a few years ago, changing the popular XT500 into an SR500. This bike was fondly regarded by traditionalists who really wanted a big kickstarting thumper, but it didn’t make enough converts from the mainstream of motorcycling for Yamaha to justify production. The numbers simply weren’t there, so the SR was quietly dropped from the 1982 lineup.

Now Honda has stepped in where Yamaha feared to tread further, with the FT500 Ascot, another street machine based on a dual purpose bike. If it seems a risky business bringing the Ascot in be-

fore there’s grass on the SR’s grave, Honda is quick to point out that their own thumper provides a couple of important amenities missing from the old SR, namely a counterbalancer and an electric starter. It is also their contention that Yamaha did not take the development of the SR engine as far as they might have. So with the electric starter and a smoother, more powerful engine, Honda hopes to attract not only the old thumper fans, but a new crowd of owners who might have been put off by the challenge of kicking life into a 500 Single. Broadening the bike’s appeal is intended to make it acceptable not only to commuters looking for inexpensive, reliable transportation, >

but to hard-core sport riders as well. A dual purpose machine for the road, if you will.

You can feel the Ascot’s XL heritage as soon as you sit on it. The FT has low, flat handlebars but there’s no stretching down and forward to reach them. The high steering head, dirt bike style, puts the bars straight out ahead of you at easy arm’s length. Seen side by side, drawings of the XL and FT frames show them to be remarkably similar, but there are still some differences.

The Ascot gets bigger frame pipes than the XL—the front downtube, for instance, has a diameter of 38.1mm vs. 34mm for the XL—and gusseting is different around the steering head. Not heavier, just different because of a change in frame loading. Honda says the larger tubing in the frame is partly for strength and partly to give the frame a heftier, more solid look that street riders

are supposedly used to. Most other frame changes have to do with bracketry, such as making a place to bolt the centerstand and providing attachment points for a longer seat.

Suspension travel has also been reduced, of course. The Ascot has 6.3 in. of front fork travel and 3.5 in at the swing arm, where the XL had 8.0 in and 7.0 in., respectively. The leading axle front forks use dual low friction bushings for reduced stiction and have air caps with separate filler valves. The forks also have a very solid looking machined aluminum brace bolted across the tops of the sliders, adding extra rigidity to an already healthy set of fork tubes. The cross brace is held on by four alien screws with plastic caps over them to keep dirt and moisture out. The rear swing arm is boxsection steel tube and uses CR type adjusters. These have sliding axle carriers inside the swing arm tube, adjusted by draw bolts at the swing arm ends. Stamped marks on the axle carriers are used for alignment, and a decal on the

swing arm warns when the chain is stretched to replacement length.

Rear shocks have five spring preload positions, but no variable damping adjustment. They are mounted “upsidedown,” with the shock body at the top and the rod end attached to the swing arm. The spring preload adjuster is at the top of the shock, protected from road crud by the swoopy-looking molded sidecover.

Honda has begun using cast aluminum wheels in place of ComStars on several of its new bikes this year. The Ascot joins the 750 Nighthawk, Sabre and Magna in having cast wheels, and the word is more will be coming though this way in the future. Honda still maintains the ComStar is a good wheel and an excellent compromise between the ride characteristics of spoked and cast wheels, but admits there is still a segment of the buying public who think ComStars look cheap.

In the past, Honda was supposedly unhappy with the uniformity and quality of cast wheels, but they claim casting and testing techniques have now improved. All their cast wheels are now' pressure tested—from the outside in—at 60 psi to check for leaks or other flaws before they go on the bikes. In any case, the wheels are a handsome, symetrically spoked design that looks a lot less stamped out than the ComStars.

Beyond general frame dimensions, the Ascot’s kinship to the XL also shows up in the engine, which is very little changed for street use. Except for the carb, oil sump, exhaust plumbing and electric starter, there is no difference between them. The engine is a sohc four-valve Single with a slightly undersquare bore and stroke of 89 x 90mm. The cam rides directly on the aluminum of the head casting and is driven by a Hy-Vo chain driven off a sprocket at the right side of the crank. Chain slack is taken up by a spring loaded slipper that now has an automatic adjuster, so the owner doesn’t have to keep an ear cocked for chain rattle and wonder if it’s time to get out the wrench again.

The four valves are opened by two forked rocker arms, accessible under separate exhaust and intake valve covers. Valve adjustment is by lock nut and screw adjuster, each with the usual tiny square nub that has to be gripped by a special Honda tool no longer provided in Honda tool kits.

Two intake valves provide greater" valve area and better flow than a single large valve, with lower reciprocating weight for the individual valves so the cam and valve springs can handle them better. Honda might have made do with a single exhaust port, but using two smaller exhaust pipes allows the exhaust system ' to clear the main dowmtube on the frame without an offset port. Also, smaller tubes can be bent more sharply away from

front wheels and fenders on long-travel suspensions like those on the XL and XR. Better cooling around the ports is another benefit. The Ascot’s pipes join just beneath the engine and flow into a well tucked-in muffler on the right side of the bike.

The FT engine uses dual counterrotating balancers to offset the vibrations of the big Single. One is located on a shaft in front of the crank and the other spins on the left end of the transmission mainshaft. Both are driven off the crank by a single roller chain. The weights have been slightly rebalanced to provide the smoothest engine operation at normal highway cruising speeds.

The clutch, driven by a straight cut gear off the crank, has been beefed up a bit on all the 500 Singles this years. Slightly heavier clutch springs are used and the clutch basket is now stronger at the base of the clutch plate fingers. The steel plates have thickened from 1.2mm to 1.6mm to handle the added punishment of hard launches on road surfaces

that don’t allow much tire spin. Pavement doesn’t move when the bike accelerates, while dirt does.

Sustained high speed running on the highway can also cause higher peak engine temperatures than the usual fastand-slow off road riding, so a small finned sump has added 0.4 qt to the oil capacity for better cooling. Part of the new sump casting is a cup-like oil filter with a replaceable paper filter element. The oil level is checked with a plastic dipstick on the right side of the engine.

So much for the small-time improvements. The big addition to the FT engine, of course is the electric starter.

As might be expected, Honda worried a bit about bolting an electric starter to the Ascot. Big Single tradition has it that Real Motorcyclists can start their own bikes, thank you, without the intercession of added weight and electrical gear. Starting a thumper is just a matter of knowing the ritual and, as Henry says, holding your mouth just right.

Usually.

But as owners of SR500s and most earlier Singles know, when a 500 doesn’t want to start, it really doesn’t want to start. And you can become a very, very tired would-be motorcyclist trying to find out why not. With that in mind, Honda decided the small penalty in weight was worth the convenience of an electric starter. Going electric also allowed them to leave off the compression release and the kick starter (meaning the bump-start is now required technique for those with flat batteries).

Starting the bike on a cool morning makes you glad Honda decided to put an electric starter on the 500. Unless the carb is primed just right with a couple flicks of the throttle and accelerator pump, the engine can crank over for several seconds on full choke before firing. Not a hard bike to start, but each time you hear that piston issue a muffled “tupff!” as it rises and falls you are thankful you didn’t have to personally heave your weight up on a kick starter and give it a giant lunge. An electric starter is also >

nice at stoplights when the bike decides it’s time to go on reserve, but you haven’t switched the petcock position. In short, it saves a lot of trouble, particularly for running around on short errands.

While the starter mechanism works very well, if a bit noisily, it is clearly an afterthought, bolted on behind the cylinder rather than integrated into the cases. The starter motor drives a ring gear on the left side of the crank through a reduction box. The starting gear is positively engaged by a solenoid until the engine fires and the gear is thrown back out of mesh on a Bendix-type shaft. This provides the slip-free torque to crank the big Single over, while preventing the engine from revving the starter motor into oblivion.

To handle the extra load of the starter,

the FT has a 12v, 14ah battery and a 170w charging system regulated to increase charge in low and medium rpm range so the battery stays well charged. The system also includes a regulator for the headlight which shuts off peak output to the light, but produces a stronger beam at lower rpm.

Once the Ascot fires on full choke, you can quickly reduce it to about half choke and the engine settles down to a nice even idle. The engine warms up quickly and the handlebar-mounted choke knob can be pushed all the way in after a few blocks of riding. The carburetor on the FT is a 35mm CV with an accelerator pump, rather than the 32mm slide throttle carb used on the XL, and it works beautifully. In fact, quite a few street bikes out there could take carburetion and rideability lessons from the Ascot. There are no flat spots on acceleration, no lag, hesitation, lean surge or other signs

of ill temper we’ve come to fear from big pistons and cylinders leaned-out to keep the EPA happy. There’s never any reluctance in taking the bike for a quick jaunt because it runs so well during warm up and responds to throttle movement without balking. The only hint of any leanness is a muffled burble or, at higher rpm, an occasional backfire when the throttle is suddenly backed off.

Noise laws have seen to it that the exhaust note is not the 500 thumper bellow of yesteryear, but at least the Ascot has a low-respectable exhaust note rather than the more lawnmowerish sound of the old SR500 or the new 450 Hawk.

Clutch feel is light and positive and the gearshift works smoothly without protest or missed gears. The Ascot’s internal gearbox ratios are the same as those on the XL, but the rear sprocket has dropped a tooth for slightly higher gearing. At 60 mph the engine is turning only about 4400 rpm. With a smooth, counterbalanced Single this pace seems pleasant and almost leisurely, especially with the engine firing one fourth as often as a Four.

As might be expected, the Ascot has a broad powerband. It pulls solidly from 3000 rpm up, but loses its stump-pulling feel if the revs drop too low. Below 3000 rpm it will buck and falter if any sort of roll-on is attempted. From 3000 to 4000 rpm the power builds rapidly, and above 4000 the power curve feels relatively flat to redline.

The Ascot weighs 374 lb. with half a tank of fuel. This is about 6 lb. heavier than the SR500 Yamaha, which was itself no record lightweight in the history of 500 Singles. But either bike feels light and easy to handle after you’ve climbed off the average multi. Claimed power output for the FT is 33 bhp; again, a good but not remarkable figure for a 500.

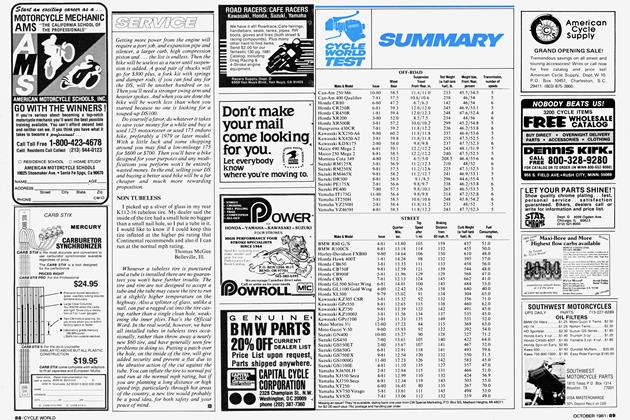

At the drag strip the Ascot turned a quarter mile time of 14.67 sec. at 85.38 mph and topped out in the half mile at 94 mph. This is just slightly faster than the times we got on the 1980 SR500 (14.74 sec. at 85.06 mph and 93 mph in the half mile), but not enough quicker that you’d notice the difference from the rider’s seat. Putting it up against a current Twin, the Ascot is almost 1 sec. and 6 mph slower through the quarter than the new 450 Hawk.

As with many bikes, however, drag strip times tell only a part of the story. Typical of machines with reasonable power to weight ratios rather than high ultimate horsepower, the Ascot accelerates quickly and is responsive at lower speeds but begins to fade a bit when it has to push bike and rider through the air at speeds above 75 mph. On most level roads the Ascot is doing well to peg its 85mph speedometer, unless the rider is tucked in.

This is not to say the bike feels overworked or overrevved on the highway—

One Cylinder Done Right

ice looking bike,’’said the guy at the illigas station. “New Honda Twin?” No, we explained, this was the new Honda Ascot, a 500cc Single. It looked a little bit like a Twin because it had two exhaust pipes, but that was because it had a four-valve head with two separate exhaust ports.

He stood back and took another look, puzzled. “Why would anyone want a 500 with just one cylinder?”

Where to start.

Those who view motorcycling with a casual outside interest, like our friend at the station, have probably looked around and concluded that most motorcycles get more cylinders as they get bigger, and that only dirt bikes or small street bikes for beginners pull up to the gas pumps in Single form. For the most part, that observation is correct.

In a former era the roadgoing thumper may have been the mainstay of daily transport and road racing, but these days there are precious few 500cc single cylinder BSAs, Nortons, Velocettes, Guzzis, AJs, Matchlesses, Sunbeams, Rudges, (enough!) etc. rolling down the highways to remind us of their former popularity. In fact, the only modern, mass-produced roadgoing Single, Yamaha’s SR500, has been dropped from the lineup after only three years of production.

Why so few road bikes in this traditional form? Edward Turner, tireless designer of British Twins, wrote a technical paper back in the Thirties enumerating the faults of the big Single. Among them: vibration from poor primary balance; heavy drive train components to handle the hammer blows of one large piston

(rather than the gentle patter of two or more smaller ones); cranky starting; a greater likelihood of detonation, and a thoroughly confused fuel/air mixture in the stop-and-start flow of the great big intake tract. Overall, he said, vibration in the 500 Single made the engine its own worst enemy.

Yet none of this discouraged people from producing, buying, selling, collecting and relishing 500 Singles for years thereafter, right up to the present. If you could ask all these past and present owners to reduce the appeal of the big thumper to a single descriptive word, that word would probably be Simplicity. For many people who like to tinker with their own motorcycles, (or hate to) there is something satisfying about one rubber fuel line leading to one carburetor that feeds an only child of a piston fired by a solo spark plug, high tension lead and coil. You can trace this oneness through the bottom end as well. The happy side effects of this simplicity are ease of maintenance, narrowness, economy and relatively light weight. And a Single sounds nice going down the road. You can hear and feel combustion at work.

So there are good and bad things about big Singles.

But what if someone came along and eliminated some of the bad things? Wouldn’t it be nice if you could have a big thumper that started easily, vibrated less than a lot of Twins and had spot-on carburetion?

Yes it would. And Honda has to be commended for doing just that and keeping the thumper tradition alive in the showroom and on the road.

it’ll cruise at an easy 70 mph all day—but it just doesn’t have the horsepower to overcome greater wind resistance as speeds approach the 90 to 100 mph range. At anything in the neighborhood of legal road speeds, however, the Ascot cruises with a pleasant, relaxed gait and responds to throttle movement with instant, lively acceleration.

Where the Ascot really shines is on curving roads. For a fast Sunday morning ride in the country or down some canyon road the bike is a joy to ride. It feels like a narrower Hawk with better low-end throttle response. And that is to say the machine does almost nothing to come between the rider’s wishes and where the bike goes in a corner. Neutral handling, rock-like stability, excellent cornering clearance and light weight all work together to make fast curves something you get through on will, rather than muscle power. Narrowness and light weight, es-

pecially, make side-to-side cornering transitions easy. A hard application of power mid-corner will move the rear tire out at a predictable rate, but the front tire stays planted and never feels as though it’s going away.

Sporting riding brings out the best in the Ascot’s appeal to the dirt track look. The pegs plant the rider’s feet directly beneath his center of gravity and the high, wide bars make it easy to lever the bike into tight turns.

In cruise mode, though, the bars, pegs and instruments seem a little too high, and the pegs too far forward. We’d guess Honda expects the Ascot to be used more in town, where the dirt track stance helps, and less on long trips, where it doesn’t.

The seat is comfortable, but has a mild banana/sling contour. This works well enough for short trips or sport riding, but on the long haul it’s hard to move rearward and stretch your back muscles. The

seat wants the rider to sit in its low, front section, and if he moves back, gravity or a quick touch of the brakes will slide him forward again. This is only a minor annoyance on a bike that is otherwise comfortable, even for tall people. The rear pegs look high and the back half of the seat appears short, but passengers of all but huge dimensions found the rear seat comfortable on day rides.

The Ascot has single disc brakes front and rear with twin-piston calipers. Brake feel is good, and while the FT didn’t set any new records for short stops, it hauled down from 30 mph in 31 ft. and from 60 mph in 143 ft., good normal distances for a current sport bike. One rider complained that the rear disc was overly sensitive, but a slightly lighter touch with the right toe cures that problem after a little familiarity.

Instrumentation on the Ascot is simple and straightforward. It has rectangular >

shaped tach and speedometer pods with turn, high beam and neutral lights between them. The horn, turn signals and high/low beam headlight switch are well separated and easy to reach on the left cluster. The rectangular halogen headlight has plenty of reach and puts out a nice wide beam on low, though we still prefer the appearance of big, round headlights on motorcycles.

In styling the Ascot, however, Honda has made no attempt to make the bike look like an old or traditional design. The rectangular instruments, integrated seat and tank and the upswept flying-cape look of the body panels are all done in current Honda sport bike style. No wire spoked wheels, teardrop tanks or round headlights.

The Ascot managed 61 mpg on our test loop, and dropped to a low of only 48 mpg during some hard mountain riding. The gas tank looks small but holds 3.4 gal., enough to propel the bike about 164 mi. to reserve and just over 200 mi. before it runs dry.

We frequently get letters from both new and veteran riders bemoaning the weight, cost, complexity, senseless flash, and difficulty of repair with many of the new high-tech bikes and their turbos, fuel injection systems, digital readouts, brain boxes and so on. There are still people who like to buy and maintain their own bikes without ever going near a dealer’s repair shop, and those who prefer to rebuild their own engines when necessary.

In the Ascot, Honda has produced an alternative to complexity, a sort of antithesis to its own CX500 Turbo. The FT is a simple, ruggedly built motorcycle with ample power, good handling, reasonable comfort, easy starting, low vibration and a strong, proven engine that produces good mileage. And it’s just light enough to put some of the fun back in riding for people who have wearied of big, heavy bikes. Like many roadsters from the premulti era, you can take the Ascot on almost any kind of road without fear of getting stuck or wallowed in. As we' discovered on one weekend trip, the FT works as well on dirt and gravel roads as it does on pavement. The bike has enough sporting flair to appeal to old hands, yet is economical enough to attract commuters and new riders. List price on the Ascot is only $2198.

Historically, few companies have been as successful as Honda at taking an unusual engine configuration and overwhelming any public objection with technical refinement. And now that the big street thumper can be regarded as something unusual, Honda has managed, to do it again. They’ve built a 500cc roadgoing Single that starts and doesn’t shake. IS

HONDA

FT500 ASCOT

$2198