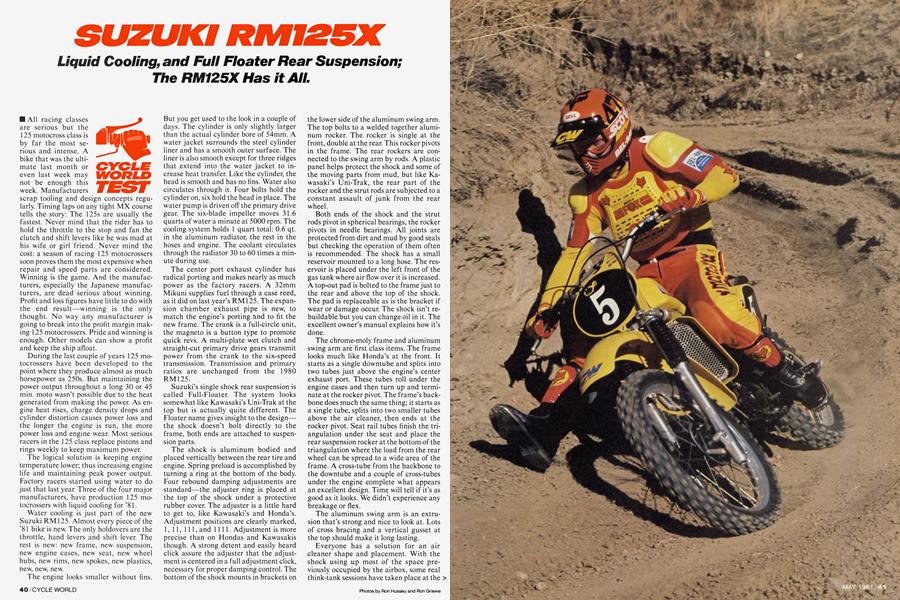

SUZUKI RM125X

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Liquid Cooling, and Full Floater Rear Suspension; The RM125X Has it All.

All racing classes are serious but the 125 motocross class is by far the most serious and intense. A bike that was the ultimate last month or even last week may not be enough this week. Manufacturers scrap tooling and design concepts regularly. Timing laps on any tight MX course tells the story: The 125s are usually the fastest. Never mind that the rider has to hold the throttle to the stop and fan the clutch and shift levers like he was mad at his wife or girl friend. Never mind the cost: a season of racing 125 motocrossers soon proves them the most expensive when repair and speed parts are considered. Winning is the game. And the manufacturers, especially the Japanese manufacturers, are dead serious about winning. Profit and loss figures have little to do with the end result—winning is the only thought. No way any manufacturer is going to break into the profit margin making 125 motocrossers. Pride and winning is enough. Other models can show a profit and keep the ship afloat.

During the last couple of years 125 motocrossers have been developed to the point where they produce almost as much horsepower as 250s. But maintaining the power output throughout a long 30 or 45 min. moto wasn’t possible due to the heat generated from making the power. As engine heat rises, charge density drops and cylinder distortion causes power loss and the longer the engine is run, the more power loss and engine wear. Most serious racers in the 125 class replace pistons and rings weekly to keep maximum power.

The logical solution is keeping engine temperature lower; thus increasing engine life and maintaining peak power output. Factory racers started using water to do just that last year. Three of the four major manufacturers, have production 125 motocrossers with liquid cooling for ’81.

Water cooling is just part of the new Suzuki RM 125. Almost every piece of the ’81 bike is new. The only holdovers are the throttle, hand levers and shift lever. The rest is new: new frame, new suspension, new engine cases, new seat, new wheel hubs, new rims, new spokes, new plastics, new, new, new.

The engine looks smaller without fins.

But you get used to the look in a couple of days. The cylinder is only slightly larger than the actual cylinder bore of 54mm. A water jacket surrounds the steel cylinder liner and has a smooth outer surface. The liner is also smooth except for three ridges that extend into the water jacket to increase heat transfer. Like the cylinder, the head is smooth and has no fins. Water also circulates through it. Four bolts hold the cylinder on, six hold the head in place. The water pump is driven off the primary drive gear. The six-blade impeller moves 31.6 quarts of water a minute at 5000 rpm. The cooling system holds 1 quart total: 0.6 qt. in the aluminum radiator, the rest in the hoses and engine. The coolant circulates through the radiator 30 to 60 times a minute during use.

The center port exhaust cylinder has radical porting and makes nearly as much power as the factory racers. A 32mm Mikuni supplies fuel through a case reed, as it did on last year’s RM 125. The expansion chamber exhaust pipe is new, to match the engine’s porting and to fit the new frame. The crank is a full-circle unit, the magneto is a button type to promote quick revs. A multi-plate wet clutch and straight-cut primary drive gears transmit power from the crank to the six-speed transmission. Transmission and primary ratios are unchanged from the 1980 RM125.

Suzuki’s single shock rear suspension is called Full-Floater. The system looks somewhat like Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak at the top but is actually quite different. The Floater name gives insight to the design— the shock doesn’t bolt directly to the frame, both ends are attached to suspension parts.

The shock is aluminum bodied and placed vertically between the rear tire and engine. Spring preload is accomplished by turning a ring at the bottom of the body. Four rebound damping adjustments are standard—the adjuster ring is placed at the top of the shock under a protective rubber cover. The adjuster is a little hard to get to, like Kawasaki’s and Honda’s. Adjustment positions are clearly marked, 1, 11, 111, and 1111. Adjustment is more precise than on Hondas and Kawasakis though. A strong detent and easily heard click assure the adjuster that the adjustment is centered in a full adjustment click, necessary for proper damping control. The bottom of the shock mounts in brackets on the lower side of the aluminum swing arm. The top bolts to a welded together aluminum rocker. The rocker is single at the front, double at the rear. This rocker pivots in the frame. The rear rockers are connected to the swing arm by rods. A plastic panel helps protect the shock and some of the moving parts from mud, but like Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak, the rear part of the rocker and the strut rods are subjected to a constant assault of junk from the rear wheel.

Both ends of the shock and the strut rods pivot in spherical bearings, the rocker pivots in needle bearings. All joints are protected from dirt and mud by good seals but checking the operation of them often is recommended. The shock has a small reservoir mounted to a long hose. The reservoir is placed under the left front of the gas tank where air flow over it is increased.

A top-out pad is bolted to the frame just to the rear and above the top of the shock. The pad is replaceable as is the bracket if wear or damage occur. The shock isn’t rebuildable but you can change oil in it. The excellent owner’s manual explains how it’s done.

The chrome-moly frame and aluminum swing arm are first class items. The frame looks much like Honda’s at the front. It starts as a single downtube and splits into two tubes just above the engine’s center exhaust port. These tubes roll under the engine cases and then turn up and terminate at the rocker pivot. The frame’s backbone does much the same thing; it starts as a single tube, splits into two smaller tubes above the air cleaner, then ends at the rocker pivot. Seat rail tubes finish the triangulation under the seat and place the rear suspension rocker at the bottom of the triangulation where the load from the rear wheel can be spread to a wide area of the frame. A cross-tube from the backbone to the downtube and a couple of cross-tubes under the engine complete what appears an excellent design. Time will tell if it’s as good as it looks. We didn’t experience any breakage or flex.

The aluminum swing arm is an extrusion that’s strong and nice to look at. Lots of cross bracing and a vertical gusset at the top should make it long lasting.

Everyone has a solution for an air cleaner shape and placement. With the shock using up most of the space previously occupied by the airbox, some real think-tank sessions have taken place at the factories. Suzuki’s engineers may have come up with the best design yet. Rather than try to fit an odd shaped single air cleaner in an even odder shaped airbox, they used two air cleaners. So what, you say. Yamaha’s first Monoshock also had two air cleaners, and they were miserable to maintain. Suzuki’s approach is different and effective. The airbox fits around the shock and forms a place for a single flat foam filter on each side. Using a flat filter, or actually two flat filters on each side, one coarse foam, one fine foam, has several advantages. Incoming air isn’t restricted, the filters are easy to make, and they don’t have glued seams to come apart. But the design goes beyond the obvious when looked at carefully. Each side has its own water drain and water that gets splashed into the air intake opening hits a baffle plate, then gets routed around the filter foam and exits the one-way drain. Each filter is squeezed between a plastic waffle shaped grid that has plastic pegs to keep the foam pieces in place. The sealing edge on each grid is raised so complete sealing is easy even when ungreased. Additionally, the outside cover is a male/female fit.

It’s not often we see a bike with new hubs at both ends. But the Suzuki has them. And both are fresh designs. The shape of each is different from anything we’ve seen before. They are more or less conical shapes with strengthening ribs that do double duty as cooling fins. Brake drums are recessed deeply into the hub so the loading on spokes is more even when the brakes are applied. Backing plates are recessed also and combined with the straight-pull spoke design lend a strange new appearance.

Straight-pull spoke designs have been reputed as being stronger and needing less

maintenance. Bending a spoke sharply after leaving the hub like most designs, makes the spoke weaker at the bend. Most break at or near the bend when problems occur. Eliminating the bend means the spoke is stronger than one that’s bent. It’s also much easier to replace straight-pull spokes if one does bend. Recessing the backing plate also allows the spoke flange on the drum side to extend past the backing plate. Spoke replacement is easier and broken spoke ends don’t fall into the brake drum where they can rip up the braking components.

Takasago aluminum rims are still used. They are famous for being soft and bending easily. The ones on the Suzuki are thicker and hold up as well as any on the market. Even the stock Bridgestone tires are very good. They are soft rubber compounds and grip well on most types of ground. Doesn’t matter what rider level you are, even our pro testers liked them.

The RM is one of the few motocross machines from Japan that still has a side stand. Dealers like them, racers don’t. Anyway, the unit is well designed and easily removed for racing.

It’s hard to complain about a bike with so many major pieces that've been so radically redesigned, especially true when the new pieces work as well as they do on the X. But it would be nice if the shift lever folded, and the throttle was a straight-pull design, and the hand levers were doglegged.

End of complaints. They’re minor anyway. The rest of the bike is so good nobodys going to worry about buying a folding shift lever.

Starting the RMX is a straight forward affair. Pull the choke on, kick the lever a time or two, and the engine is running. Now, warm it up for 5 min. . . . that’s what the owner’s manual says. Quite a different approach from an air cooled engine. Setting still for 5 min. with the engine running could burn up an air cooled 125. Engine tones are different from an engine that’s water cooled. The layer of water and doubled steel liner around the piston deadens much of the ring associated with twostrokes. The engine sounds potent and torquey blipping the throttle while engine temperatures stabilize. A high frequency buzz comes through the nicely padded RM seat but disappears as soon as the clutch is released.

Finding fault with the bike while on the track is nearly impossible. If it does anything wrong, our pro, intermediate and novice riders couldn’t detect it. Engine power is strong. The first quarter throttle doesn’t do a whole lot, like any highly tuned 125. After a quarter throttle, hold on. The RMX even pulls heavier riders at incredible rates of acceleration. Shifting is precise and quick. Forget the clutch once moving, just jam the next gear. Gear ratios are perfect for the engine’s power output and there is a gear for every track condition. Just peg the throttle and shift, shift—-and like any 125 motocrosser— shift again if in doubt. Don't worry about overwinding the engine if the throttle is left to the stop while shifting, the ignition has an automatic rev limiter built-in. If revs go too high, the ignition cuts out, saving the owner from buying engine parts like rods and cases.

Being first into the first corner is no problem on the RM. And you may have to have one to get there first. We raced the bike at the pro, intermediate and novice levels. It won the drag to the first corner in every event it was entered in. Several races were heavy with new YZ125 waterpumpers; the RM pulled them easily. We didn’t get the chance to race a new Kawasaki or Honda 125 so don’t know about them yet. But, the bike didn’t get outdragged by any 125 we raced it against, including several highly modified pro racer’s 125s.

Getting the X stopped once into the first corner is no problem either. Brakes at both ends are near perfection. The full-floating rear doesn’t chatter or lock the suspension on rough downhills and rider feel and control are great. The front is equally strong and controllable. Lever pressure is light and rider feel excellent.

Several riders voiced concern about the radiator placement. The plastic air scoop looks as if it would hit a tall rider’s knees. And it does. But it doesn’t interfere with control and although the rider can feel it, > it’s no problem. Part of the reason the rider is able to touch the scoop is because he can move so far forward on the bike. The flat topped tank allows rider weight placement far forward on the chassis. Great for those slippery corners where the front tire wants to skate.

SUZUKI RM125X

$1579

Handling is neutral. Cornering techniques are completely up to the rider; the RMX doesn’t have any preference. It’ll take the tight inside line, ride high on the berm, low on the berm, slide, or simply ride through, whatever the rider wishes. The same, do-anything-the-rider-wishes handling is available overjumps. Front up, front down, full-lock cross-up—all are easy if the rider has the ability.

Suspension compliance and control are perfect. Forget about the back of the bike kicking over lipped holes and such, it won’t happen. Getting the rear wheel to kick is almost impossible. The rear suspension just soaks up the bump, never transfering the jolt to the rider. No jump is big enough to bottom the rear either. The sus-

pension is progressive and absorbs even the hairiest drops without complaint. We experimented with different damping settings but liked the stock 1 1 position best. Spring preload for the rear felt too soft before we rode the bike. Under actual use, it is perfect as is.The forks are nearly as good. The damping felt a little stiff and the balance between front and rear suspension was improved considerably by changing the fork oil to 5 weight. We used the stock oil level setting, 6.6 in. from the top of the bottomed out fork tubes. The front then felt too soft in the shop, but proved perfect on the track for our easier riders. Our pros added 2 psi of air to prevent bottoming.

We didn’t have one mechanical failure with the new RM. And we gave it every opportunity to break. It was raced to first place in the novice, intermediate and pro classes at local MX tracks. We didn’t find one rider who didn’t like the little buzz bomb. Even confirmed big bore riders thought the bike was a blast to ride. And after all, isn’t fun the name of the game? 0