Eight Hours of Suzuka

The Race Ain't Over 'Til The Fat Man Crashes

John Ulrich

"The push,” I said to myself between breaths as I strained with the weight of my Moriwaki Kawasaki, struggling to move it forward against the resistance of gravity and the lumpy grass lining Japan’s Suzuka circuit, “is what . . . makes . . . endurance racing . . . different.

“The push . . . after the crash . . . with still ... a chance ... of finishing well . . .” You can’t crash in a sprint race and have any hope of a good finish, that’s for sure. Yet I knew that even as I struggled and heaved and sweated trying to roll my damaged bike back to the pits, that if I could just get there without losing too much time, if my partner and I could still ride it in spite of the damage, that maybe, just maybe, by the end of the eight long hours of racing we could be up near the front in this, my first World Championship endurance race.

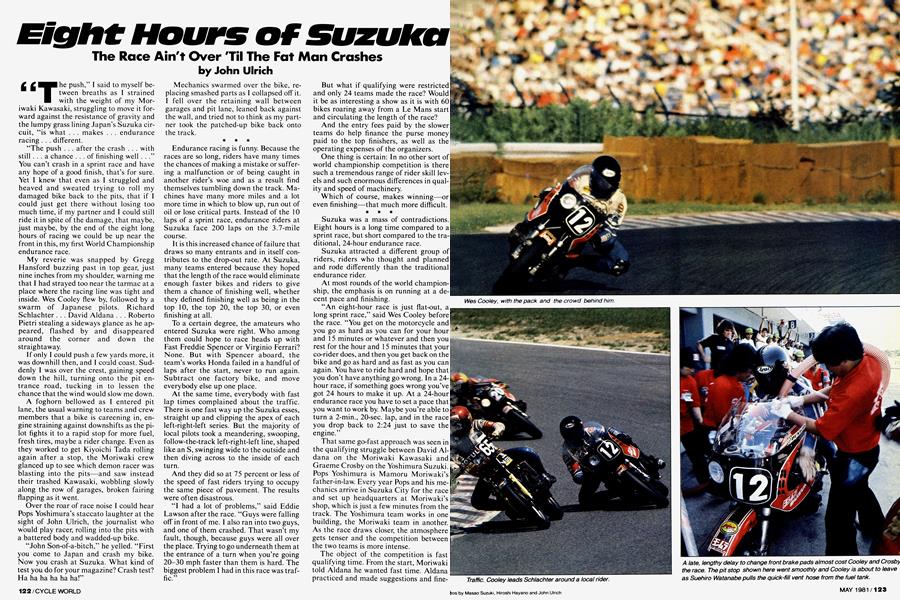

My reverie was snapped by Gregg Hansford buzzing past in top gear, just nine inches from my shoulder, warning me that I had strayed too near the tarmac at a place where the racing line was tight and inside. Wes Cooley flew by, followed by a swarm of Japanese pilots. Richard Schlachter . . . David Aldana . . . Roberto Pietri stealing a sideways glance as he appeared, flashed by and disappeared around the corner and down the straightaway.

If only I could push a few yards more, it was downhill then, and I could coast. Suddenly I was over the crest, gaining speed down the hill, turning onto the pit entrance road, tucking in to lessen the chance that the wind would slow me down.

A foghorn bellowed as I entered pit lane, the usual warning to teams and crew members that a bike is careening in, engine straining against downshifts as the pilot fights it to a rapid stop for more fuel, fresh tires, maybe a rider change. Even as they worked to get Kiyoichi Tada rolling again after a stop, the Moriwaki crew glanced up to see which demon racer was blasting into the pits—and saw instead their trashed Kawasaki, wobbling slowly along the row of garages, broken fairing flapping as it went.

Over the roar of race noise I could hear Pops Yoshimura’s staccato laughter at the sight of John Ulrich, the journalist who would play racer, rolling into the pits with a battered body and wadded-up bike.

“John Son-of-a-bitch,” he yelled. “First you come to Japan and crash my bike. Now you crash at Suzuka. What kind of test you do for your magazine? Crash test? Ha ha ha ha ha ha!”

Mechanics swarmed over the bike, replacing smashed parts as I collapsed off it. I fell over the retaining wall between garages and pit lane, leaned back against the wall, and tried not to think as my partner took the patched-up bike back onto the track.

Endurance racing is funny. Because the races are so long, riders have many times the chances of making a mistake or suffering a malfunction or of being caught in another rider’s woe and as a result find themselves tumbling down the track. Machines have many more miles and a lot more time in which to blow up, run out of oil or lose critical parts. Instead of the 10 laps of a sprint race, endurance riders at Suzuka face 200 laps on the 3.7-mile course.

It is this increased chance of failure that draws so many entrants and in itself contributes to the drop-out rate. At Suzuka, many teams entered because they hoped that the length of the race would eliminate enough faster bikes and riders to give them a chance of finishing well, whether they defined finishing well as being in the top 10, the top 20, the top 30, or even finishing at all.

To a certain degree, the amateurs who entered Suzuka were right. Who among them could hope to race heads up with Fast Freddie Spencer or Virginio Ferrari? None. But with Spencer aboard, the team’s works Honda failed in a handful of laps after the start, never to run again. Subtract one factory bike, and move everybody else up one place.

At the same time, everybody with fast lap times complained about the traffic. There is one fast way up the Suzuka esses, straight up and clipping the apex of each left-right-left series. But the majority of local pilots took a meandering, swooping, follow-the-track left-right-left line, shaped like an S, swinging wide to the outside and then diving across to the inside of each turn.

And they did so at 75 percent or less of the speed of fast riders trying to occupy the same piece of pavement. The results were often disastrous.

“I had a lot of problems,” said Eddie Lawson after the race. “Guys were falling off in front of me. I also ran into two guys, and one of them crashed. That wasn’t my fault, though, because guys were all over the place. Trying to go underneath them at the entrance of a turn when you’re going 20-30 mph faster than them is hard. The biggest problem I had in this race was traffic.”

But what if qualifying were restricted and only 24 teams made the race? Would it be as interesting a show as it is with 60 bikes roaring away from a Le Mans start and circulating the length of the race?

And the entry fees paid by the slower teams do help finance the purse money paid to the top finishers, as well as the operating expenses of the organizers.

One thing is certain: In no other sort of world championship competition is there such a tremendous range of rider skill levels and such enormous differences in quality and speed of machinery.

Which of course, makes winning—or even finishing—that much more difficult. * * *

Suzuka was a mass of contradictions. Eight hours is a long time compared to a sprint race, but short compared to the traditional, 24-hour endurance race.

Suzuka attracted a different group of riders, riders who thought and planned and rode differently than the traditional endurance rider.

At most rounds of the world championship, the emphasis is on running at a decent pace and finishing.

“An eight-hour race is just flat-out, a long sprint race,” said Wes Cooley before the race. “You get on the motorcycle and you go as hard as you can for your hour and 15 minutes or whatever and then you rest for the hour and 15 minutes that your co-rider does, and then you get back on the bike and go as hard and as fast as you can again. You have to ride hard and hope that you don’t have anything go wrong. In a 24hour race, if something goes wrong you’ve got 24 hours to make it up. At a 24-hour endurance race you have to set a pace that you want to work by. Maybe you’re able to turn a 2-min., 20-sec. lap, and in the race you drop back to 2:24 just to save the engine.”

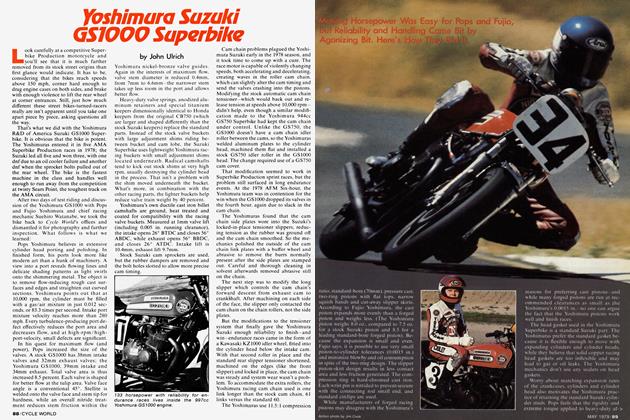

That same go-fast approach was seen in the qualifying struggle between David Aldana on the Moriwaki Kawasaki and Graeme Crosby on the Yoshimura Suzuki. Pops Yoshimura is Mamoru Moriwaki’s father-in-law. Every year Pops and his mechanics arrive in Suzuka City for the race and set up headquarters at Moriwaki’s shop, which is just a few minutes from the track. The Yoshimura team works in one building, the Moriwaki team in another. As the race draws closer, the atmosphere gets tenser and the competition between the two teams is more intense.

The object of the competition is fast qualifying time. From the start, Moriwaki told Aldana he wanted fast time. Aldana practiced and made suggestions and finetuned the suspension and when qualifying came he went out and blazed around the track in 2 min., 17.69 sec., the only rider in the 2:17 bracket. Moriwaki beamed.

Crosby’s group qualified later. Crosby looked at Aldana’s time on the official results sheet, gritted his teeth and rode onto the track. After several fast laps and with darkness about to call an end to timed practice, Crosby pulled into the pits to confer with Pops. Learning that he was still a few tenths of a second slower than Aldana, Crosby took a deep breath and shot out onto the course again, riding like' a wildman. Suddenly Crosby flashed by the finish line and shouts rang out from the Yoshimura pit.

Crosby’s time was 2:17.62, making him fast qualifier by a margin of 0.07 sec. over Aldana.

Hearing the news, Aldana slumped in. the seat of Moriwaki’s car, resting his elbows on his knees and his face in his hands.

“It’s times like this that you wonder why you even bother to race,” moaned Aldana.

Aldana’s visible disappointment shocked the experienced European endurance racers.

“That is stupid!” said a mechanic for the French Suzuki distributor’s team. “Qualifying times mean nothing! This is an endurance race.”

Not quite. It was Suzuka.

“This race is very different from other World Championship Endurance races because this race is more like a Grand Prix,” said Johann Van Der Wal of the Dutch Honda distributor’s team. “Many people enter this race and they are very good entrants.”

There is more to it than that. At most endurance races the emphasis is on running at a decent pace and finishing. Endurance bikes were never as fast as American Superbikes and didn’t have to be. Experimenters showed up at the races with all sorts of home-built motorcycles using single-shock rear suspension systems (common now but only seen on endurance bikes five years ago) and center-hub' steering.

Honda came into endurance racing with salaried riders and reliable machines and quick-fills and trained mechanics and fast pit stops and limitless financial resources and cleaned up against the homebuilt privateer bikes. Honda won and won and won, and promoted, and publicized, and advertised and made endurance racing into a big deal. It became a world championship, but the emphasis was still on plodding along and finishing.

At a typical 24-hour race, bikes run on very hard tires that last eight hours between changes.

In 1978, Americans Mike Baldwin and Wes Cooley rode a Yoshimura Suzuki Superbike at Suzuka, blazing around the track to win easily. They ran relatively soft tires and changed wheels (with fresh tires already mounted) mid-way through the event. Honda’s endurance champions Christian Leon and Jean-Claude Chemarin were lapped before they retired.

Now everybody who plans to be competitive at Suzuka runs relatively soft tires and changes wheels mid-way through the race.

The bikes are different, too.

“There are many fast bikes at Suzuka,” said Helmut Dahne, a West German who has done well in European endurance races. “It is not like in Europe, where there are only a few fast bikes. That makes it very difficult, because our bike is not so fast.”

(Dahne’s bike was fitted with an RSI000 engine, using parts built by Honda RSC for endurance racing.)

Suzuka, as short and as different as it is compared to the traditional European races, illustrates what is happening to endurance racing, how it is changing.

Fast is how endurance racing is changing. Fast riders, fast bikes. Suzuki and Kawasaki noticed the endurance crowds and publicity and Honda’s advertisements and the obvious connection between racing four-strokes and selling four-strokes, and became interested. They brought in fast riders and built fast bikes and learned how to keep those fast riders upright and those fast machines together for the duration. To meet the challenge Honda brought in its own fast riders and increased horsepower and for the first time in years faced reliability problems.

Cooley and Crosby won at Suzuka. Cooley is American Superbike Production Champion two years running, 1979-1980. Crosby won the Daytona Superbike race, the Formula One TT World Championship, and finished fourth in a 500cc World Championship Grand Prix.

Eddie Lawson and Gregg Hansford were second on a works, single-rear-shock Kawasaki. Lawson is U.S. 250cc Champion, 1980 Daytona 250cc winner and was second in 1980 Superbike points. Hansford has won several 250cc and 250cc World Championship Grands Prix, along with national championships in Australia.

Third at Suzuka were Marc Fontan and Herve Moineau on a Honda France RSI000, three laps behind. Fontan was fifth in the 1980 Daytona 200 on a TZ750, and, with Moineau, won the 1980 Assen Eight Hour and the 24-hour in Belgium, also finishing second in Italy and fifth in Austria. The pair won the Endurance World Championship with their finishes, the first time in five years that Leon and Chemarin didn’t take the title.

At the 1980 Bol d’Or, a non-championship 24-hour, Freddie Spencer (who led the 1980 Daytona 200 by 60 sec. when his bike broke) and David Aldana (who battled for the 1979 Daytona 200 lead until his Yamaha seized; and finished sixth, first on a four-stroke, at Dayton 1980) teamed on a Honda to lead four of the first seven hours before their RSI000 blew up. Fontan crashed twice, (requiring stitches the second time), while Leon and Chemarin retired with engine trouble.

Meanwhile, Pierre Samin and Frank Gross rode a perfect example of a very fast bike, a factory Suzuki GS1000R created with the assistance of Pops Yoshimura, and with that bike they won the 1980 Bol d’Or. Gross replaced Jean-Bernard Peyre, killed in a street accident in Paris. Peyre led the endurance standings before his death, finished fourth (with Samin) at Suzuka, and might have brought Suzuki and Yoshimura their first endurance championship had he not died.

World Champion Fontan won’t be endurance racing in 1981, instead going off to do the Grand Prix circuit. Christian Leon was lured to Suzuki after the 1980 season, and died while testing a GS1000R in Japan. But Honda France will be back, this time with Americans Aldana and Baldwin. To compete in endurance races this year, it will take a factory-backed four-stroke, a Yoshimura Suzuki or works Kawasaki or Honda, ridden by sprint racers. When the transformation is eventually complete, World Championship endurance racing will be dominated by outstanding fast guy riders on outstanding factory machines. While the idea that an amateur or privateer has a chance by riding consistently and finishing may persist, the chance of it happening will fade.

In isolated cases, maybe there will be another result like the Spanish 24-hour in 1980, where a Ducati won against a sparse entry on a hazardous street circuit. But overall, the idea of privateers cruising around and winning after the factories crash and burn or blow, the idea of amateur victory by attrition, must fade. The onslaught of fast guys and fast bikes will make it so.

I wasn’t alone in having crashed at Suzuka. Ron Pierce had been hurt when his Honda’s brakes failed in practice. Wes Cooley destroyed his bike, stepping off in mid-week practice. Reigning endurance champion Christian Leon broke his collarbone before the race. Australian Mick Cole, 1979 Suzuka winner, dropped the Yoshimura Suzuki at mid-race, and Eddie Lawson ran into it and fell. Countless other riders, their machines, and parts of their machines littered the pavement before the end of the eight hours.

And many recovered.

The practice crashes were easy for the factory teams. When Pierce fell, Freddie Spencer was left without a partner. But when Leon crashed, that freed up Italian 500cc GP star Virginio Ferrari, hired by Honda to replace Jean-Claude Chemarin, Leon’s usual partner, who was injured at an earlier event. So Honda teamed Spencer and Ferrari on Leon’s bike.

When Cooley crashed, he was unhurt, but his Yoshimura Suzuki's frame was bent. The next morning a little truck rolled up with a new chassis and gas tank, built overnight at the Suzuki factory racing shop.

It was a little harder for the non-factory teams, if only because they lacked spare bikes, which meant riders often missed the two-daily, one-hour practice sessions during repairs.

When lady racer Gina Bovaird, who Moriwaki asked me to ride with, crashed our bike during Tuesday practice, the Japanese doctors diagnosed a broken little finger and predicted that she could ride in a few days. It took one day to fix the bike. One more practice session was lost recovering the bike when I got a fiat front tire out on the course. A sudden storm took another practice when we were caught without rain tires.

The delay didn’t matter, and the 12-in. clutch lever Moriwaki manufactured to make shifting easier for Gina didn't help. Her hand turned deep blue and her onelap attempt at riding Thursday was hopeless—she couldn’t hold on. (Back in Los Angeles, she would learn that her hand was broken in five places, requiring immediate surgery).

So Pops Yoshimura recommended one of the riders he sponsors in Japanese club races, Yoshitada Higiwara, who dutifully showed up the next day to ride with me. With a round face, a crinkly, omniscient smile and a chunky build, Hagiwara looked like he belonged in a shrine receiving incense, which is why his friends called him Buddha Man.

With a little luck, even crashing during the race wasn’t necessarily a serious problem. When Cole crashed and took Lawson with him, Lawson jumped to his feet, picked up his works Kawasaki, kickstarted the engine and rejoined the race within 45 seconds. The crash probably cost Lawson and Hansford the race but at least they finished second to Crosby and Cooley—by 40 sec. after eight hours.

Akitaka Tomie and Kiyoichi Tada— riding another Moriwaki Kawasaki finished 10th in spite of Tomie crashing twice during the race. And Johan Van Der Wal picked up his Honda, re-installed the gas tank (flung 30 ft. when the bike tumbled off the track in the first turn), push-4 started the engine and carried on. With partner Bert Struyk, Van Der Wal worked his way from 43rd to ninth in the remaining hours of the race.

Which isn’t to say that everybody got off scot-free. The French Kawasaki distributor’s team was finished when Christian Huguet was hurt in the first hour. And when Cole fell off the bike he shared with U.S. F-l Road Racing Champion Richard Schlachter, he dislocated his shoulder, ending the team’s ride.

Okay, I’ll admit that dreams of riding a steady race and outlasting the factories to grab my share of endurance glory motivated my trip to Japan. Suzuka has always been a big race in Japan. For 1980 the biggest motorcycle event in Japan became a world championship race, the first chan> pionship round of any type held there in over a decade. Over 70,000 people came to watch the race in 1979, many riding their bikes nonstop from all parts of the country. The enthusiasm for autographs from foreign riders alone was worth the trip, said riders who had already been there, and the entry list for Suzuka 1980 was the most incredible roster of talent ever seen in endurance racing. I wanted to ride so much that I would have ridden a kangaroo, providing it was a reasonably fast kangaroo. I had it in my mind that keeping my head and convincing my partner to do the same would ensure a good finish.

continued on page 183

continued from page 128

I hadn’t counted on Gina falling in practice.

And I hadn’t counted on making a mistake in a fast turn and watching in slowmotion horror as the bike flipped upright and pitched me off the high side.

The bike hit the wall on its fourth or fifth bounce, but 1 slidby some miracle—down the track instead of off it on a tangent. A rider I almost hit crashed, as did one or two others, but they were up and gone before 1 could breathe again or move from the spot just off the track where 1 had crawled after my slide stopped.

1 rode another stint, after Hagiwara took the patched-up bike out for an hour, and was amazed to find that 1 could still ride at all.

When I handed off to Hagiwara again at the third hour, I felt loosened up and reasonably fit again. But it didn’t matter, because the front tire—evidently

damaged in my crash— blew out its sidewall in the fourth hour and pitched Hagiwara over the handlebars just after he shifted into fifth gear on the back straightaway. If there was anything still usable on the bike, it might have been the carburetors, but everything else—frame, cylinder head, cases, forks, wheels—was destroyed. Hagiwara had broken ankles and wrists but seemed in good spirits after the race. Buddha Man Hagiwara was seated serenely on a parts cart when a mechanic wheeled him into the pits. When he saw me, he apologized for crashing the bike.