MOTOCROSS

COMPETITION GUIDE

If any type of racing has caught the eye and attention of American youth, it is motocross. Tracks dot the countryside. Around population centers of the United States there may be two or three or even four road race tracks or dirt tracks, but there are bound to be dozens of motocross tracks with almost as many local race sanctioning bodies as there are tracks.

Anybody can walk into a motorcycle store tomorrow and buy a motocrosser off the showroom floor for less than $2000. That's not possible with, say, a road racer, especially not a Superbike.

Motocross has attracted such enthusiasm that an entire industry supplying trick-looking jerseys, leathers, nylon racing pants, gloves, helmets, visors, goggles, boots has sprung up and flourished with the sport.

Ever heard of high school teams being organized for road racing or dirt track? Probably not. But high school motocross has been around for half a decade.

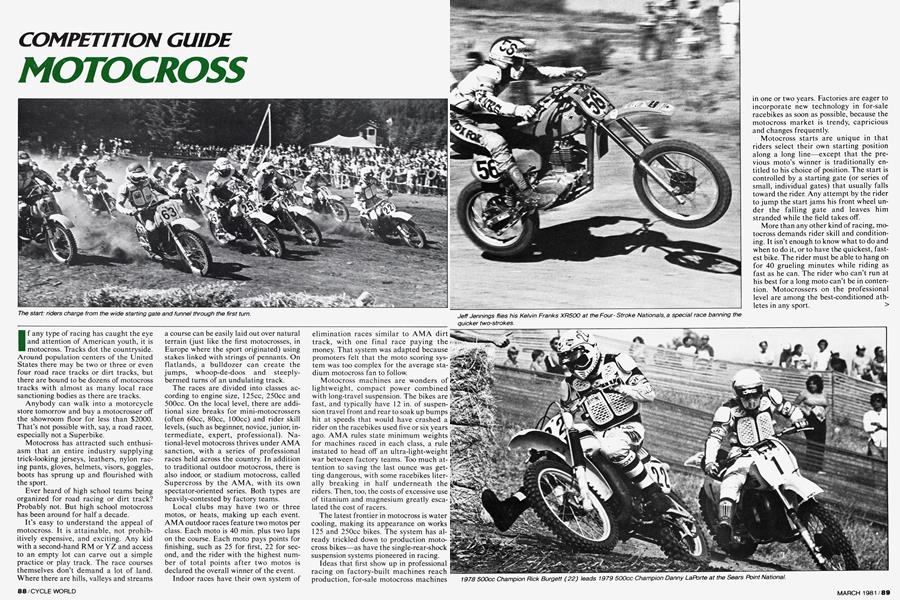

It's easy to understand the appeal of motocross. It is attainable, not prohibitively expensive, and exciting. Any kid with a second-hand RM or YZ and access to an empty lot can carve out a simple practice or play track. The race courses themselves don't demand a lot of land. Where there are hills, valleys and streams a course can be easily laid out over natural terrain (just like the first motocrosses, in Europe where the sport originated) using stakes linked with strings of pennants. On flatlands, a bulldozer can create the jumps, whoop-de-doos and steeplybermed turns of an undulating track.

The races are divided into classes according to engine size, 125cc, 250cc and 500cc. On the local level, there are additional size breaks for mini-motocrossers (often 60cc, 80cc, lOOcc) and rider skill levels, (such as beginner, novice,junior, intermediate, expert, professional). National-level motocross thrives under AMA sanction, with a series of professional races held across the country. In addition to traditional outdoor motocross, there is also indoor, or stadium motocross, called Supercross by the AMA, with its own spectator-oriented series. Both types are heavily-contested by factory teams.

Local clubs may have two or three motos, or heats, making up each event. AMA outdoor races feature two motos per class. Each moto is 40 min. plus two laps on the course. Each moto pays points for finishing, such as 25 for first, 22 for second, and the rider with the highest number of total points after two motos is declared the overall winner of the event.

Indoor races have their own system of elimination races similar to AMA dirt track, with one final race paying the money. That system was adapted because promoters felt that the moto scoring system was too complex for the average stadium motocross fan to follow.

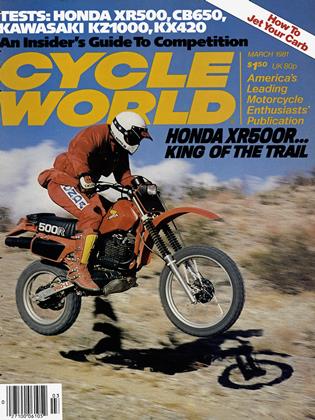

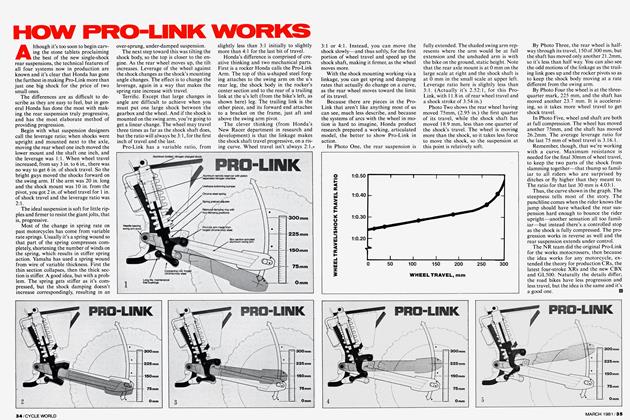

Motocross machines are wonders of lightweight, compact power combined with long-travel suspension. The bikes are fast, and typically have 12 in. of suspension travel front and rear to soak up bumps hit at speeds that would have crashed a rider on the racebikes used five or six years ago. AMA rules state minimum weights for machines raced in each class, a rule instated to head off an ultra-light-weight war between factory teams. Too much attention to saving the last ounce was getting dangerous, with some racebikes literally breaking in half underneath the riders. Then, too, the costs of excessive use of titanium and magnesium greatly escalated the cost of racers.

The latest frontier in motocross is water cooling, making its appearance on works 125 and 250cc bikes. The system has already trickled down to production motocross bikes—as have the single-rear-shock suspension systems pioneered in racing.

Ideas that first show up in professional racing on factory-built machines reach production, for-sale motocross machines in one or two years. Factories are eager to incorporate new technology in for-sale racebikes as soon as possible, because the motocross market is trendy, capricious and changes frequently.

Motocross starts are unique in that riders select their own starting position along a long line—except that the previous moto's winner is traditionally entitled to his choice of position. The start is controlled by a starting gate (or series of small, individual gates) that usually falls toward the rider. Any attempt by the rider to jump the start jams his front wheel under the falling gate and leaves him stranded while the field takes off.

More than any other kind of racing, motocross demands rider skill and conditioning. It isn't enough to know what to do and when to do it, or to have the quickest, fastest bike. The rider must be able to hang on for 40 grueling minutes while riding as fast as he can. The rider who can't run at his best for a long moto can't be in contention. Motocrossers on the professional level are among the best-conditioned athletes in any sport.