DRAG RACING

COMPETITION GUIDE

The principles of organized drag racing are scarcely more complicated than the street racing found in any American city. However, equipment is used to ensure fair starts and accurate measurement of the time it takes a bike to reach the finish line (elapsed time) and the speed it is traveling at the finish (terminal speed). And as in all organized racing, rules and regulations exist to promote safety and improved, closer competition.

Official drag racing takes place on a straight, level stretch of asphalt one-quarter-mile (1320 ft.) long, with about an equal distance beyond the finish line for racing vehicles to slow down and stop. After racing and slowing down, vehicles return to the starting area on return roads that lead away from one side of the drag strip.

Drag racing starts are controlled by a “Christmas tree.” The tree is actually a post fitted with two vertical rows of yellow, green and red colored spotlights, the post itself either being planted in the ground or suspended from wire cables like a traffic signal. The colored lights on the post reminded somebody, somewhere, sometime of a Christmas tree, and that's where the name came from.

Smaller, yellow lights on top of the tree are connected to electric eye cells in each of the dragstrip's two lanes. When a rider moves his bike into the exact, proper posi-

tion in his lane for starting, his bike's front wheel breaks two side-by-side light beams. Each beam controls one of the small, yellow staging lights atop the tree, and when both lights are on, the bike is staged and the starter can activate the tree by remote control. Each lane has its own staging lights.

Below the staging lights on each side of the tree are several amber lights, then one green light and one red light. The amber lights warn the rider that the start is coming, and at some amateur drag races at some strips as many as five amber lights

will flash on in sequence (at half-second intervals) before the green light signals the rider to go.

Typically, an amateur rider comes to the starting line, stages his machine, then watches as the tree blinks:

Yellow.

Yellow.

Yellow.

Green!

If the rider leaves the starting line— moving his bike's front wheel out of the staging light beams—before the green light, then he red lights, and the red light at the bottom of the tree comes on. That means that he jumped the start and loses the race on that technicality, even if he is the first to the finish line.

In the case of professional drag racing classes, there is only one yellow light before the green, and the green light typically follows the yellow light by only onethird of a second.

When the bike leaves the starting line, the front wheel no longer breaks the staging light beams, and that triggers the timing devices. At 1320 ft., the bike crosses the finish line light beam, stopping the electronic clocks, which determine elapsed time from the start.

But 66 ft. before the bike reaches the finish line lights, it first breaks the first mph light. At 66 ft. after the finish line lights, the bike breaks another mph light beam. The time it takes for the bike to cross the 132 ft. (one-tenth of one quarter mile) between the first mph light and the second mph light is used to calculate the bike's terminal speed. Terminal speed, then, is actually an average of the bike's speed between the first mph light and the second mph light.

Because a computer is tied into the timing equipment, not all drag racing must be between relatively equal competitors starting at the same time—which is called heads up racing. Instead, unequal machines or riders can be started through a system of handicap, or bracket racing.

In bracket racing, a rider makes several practice runs before the race, to determine how fast he can go with his machine. Then he dials in his speed, predicting to officials how fast he will go.

For example, let's say that a rider rode his CBX at the drag strip and turned elapsed times of 12.12 sec., 12.09 sec., and 12.10 sec. in the three practice runs. He decides that he can go 12.10 sec. in the bracket race, so tells that elapsed time to the officials.

When the rider goes to the starting line with his CBX, he looks over and sees another rider on a Kawasaki KZ440, who has dialed in an elasped time of 14.65 sec. The officials in the timing tower feed the elapsed time dial-ins of each rider into the starting computer. The riders stage, and the starter pushes the go button. The lights on the Kawasaki rider's side of the tree send him on his way before the CBX pilot's lights even begin to flash. By the time the CBX rider has gotten the green light, he is leaving the starting line exactly 2.55 sec. after the Kawasaki rider. In theory, the two bikes should reach the finish line at precisely the same time, but as in the case of all human efforts, that mathematical perfection doesn't occur. Instead, one rider or the other misses a shift, doesn't start perfectly, shifts at the wrong rpm, doesn't tuck in just right, whatever. Or maybe one rider turns an elapsed time quicker than his dial-in, and is disqualified for breaking out of his bracket.

While bracket racing is popular on a local participation level, national-level professional and sportsman drag racing is heads up, with dozens of complicated classes designed to even up the competition. Class formulas state how much every kind of bike must weigh based on displacement and engine type, allowing for pushrod, single overhead camshaft and double overhead camshaft engines with two valves per cylinder or four valves per cylinder. A Suzuki GS1 100 with dohc and four valves per cylinder, for example, is required to weigh more on the starting line than is a dohc Kawasaki KZ 1000 with two valves per cylinder. Machines are weighed after each pass, the rider (with equipment such as leathers and helmet) sitting on the bike as it is weighed. If a combination of motorcycle and rider isn't heavy enough to suit the formula, lead weights are typically bolted on to the front downtubes, ahead of the engine.

At the races, riders are matched in pairs for eliminations. The winner of each round of eliminations is paired with another

eliminations winner until just two—in theory the quickest two—riders are left. The finals between those two riders determines the winner of the race.

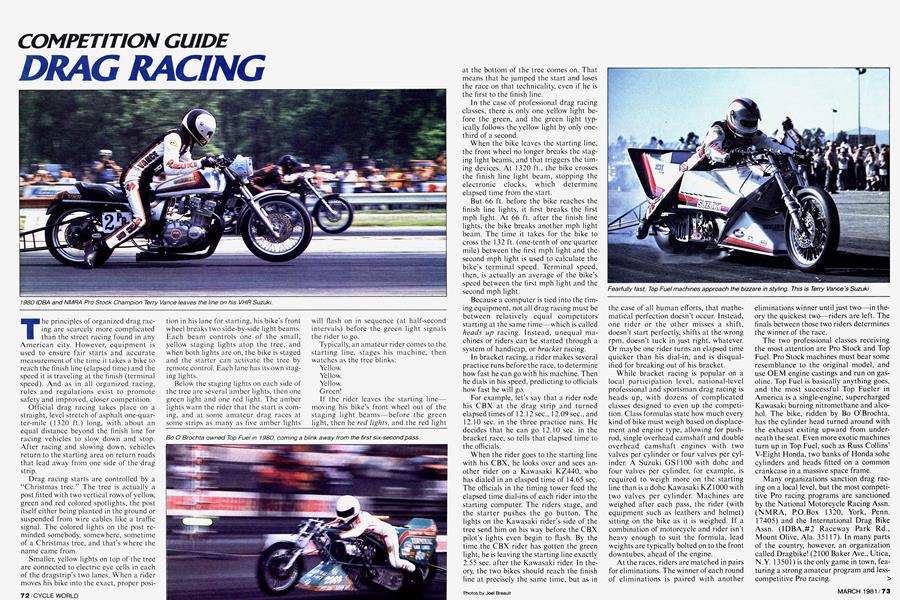

The two professional classes receiving the most attention are Pro Stock and Top Fuel. Pro Stock machines must bear some resemblance to the original model, and use OEM engine castings and run on gasoline. Top Fuel is basically anything goes, and the most successful Top Fueler in America is a single-engine, supercharged Kawasaki burning nitromethane and alcohol. The bike, ridden by Bo O'Brochta, has the cylinder head turned around with the exhaust exiting upward from underneath the seat. Even more exotic machines turn up in Top Fuel, such as Russ Collins' V-Eight Honda, two banks of Honda sohc cylinders and heads fitted on a common crankcase in a massive space frame.

Many organizations sanction drag racing on a local level, but the most competitive Pro racing programs are sanctioned by the National Motorcycle Racing Assn. (NMRA, P.O.Box 1320, York, Penn. 17405) and the International Drag Bike Assn. (IDBA,#2 Raceway Park Rd., Mount Olive, Ala. 35117). In many parts of the country, however, an organization called Dragbike! (2100 Baker Ave., Utica, N.Y. 13501) is the only game in town, featuring a strong amateur program and lesscompetitive Pro racing.