UP FRONT

FOOLS LIKE US

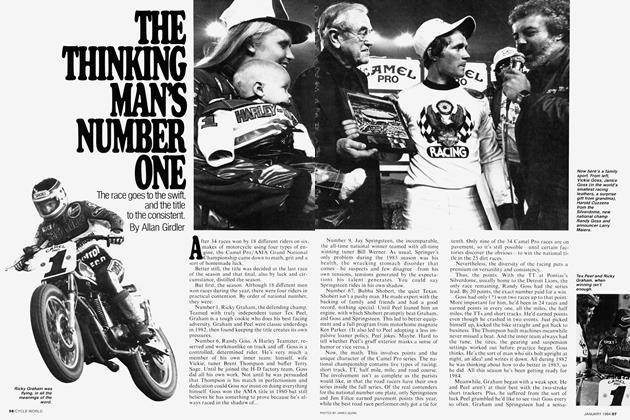

Allan Girdler

Back when I was a political reporter the newspaper where I worked was always engaged in some sort of political campaign. One day I mentioned to my boss that we were going to get whipped in the struggle of the moment, for reasons not connected to the issue, and that I didn’t like it. Well, he asked, would you prefer that we only get into fights we know we can win?

I hadn’t thought of it quite that way. No, I said, of course not. Just what the issue was I’ve long since forgotten but his lesson has stuck .with me. With that thought in mind, I present two connected propositions;

Japanese motorcycles have character, and . . .

They have character because the men who design and build and sell them like motorcycles.

There may be a generation or experience gap here. Younger riders or newcomers to the sport may not have noticed this dispute at all. They may be surprised to learn that their brand and the three competing brands were not too long ago lumped together and condescended to as cookie-cutter bikes, clones collectively known as the UJM, short for Universal Japanese Motorcycle. It happened. There used to be a man, now retired from the motorcycle press, who took people into his shop and displayed his European sports bike. Look long and well, he preached. That’s a real motorcycle and they won’t be with us much longer. Soon mass production and market research and cooperative unions and big-buck advertising budgets will drive all real motorcycles like this one from the market.

I say it’s spinach.

I say this with some surprise. That American and European bikes have character has never been a question. Everybody knows that the Davidson family

rides. When I walk through the pits at the races and see the head man for BMW’s west coast office wrenching on the production bike I say hi, not what are you doing here? I know what he’s doing. He’s doing what he likes. That Triumph testers raced on the Isle of Man wasn’t news. In fact, one British critic notes that when a BSA engineer was lectured for wearing riding clothes in the executive dining room, that was a sign the end was near. And that Count Agusta bankrolled the racing team to world titles because he plain loved engines, well, of course. And the same goes for Sr. Bulto.

But it hasn’t gone like that for the Japanese. When they first arrived in the U.S., I missed it. Oh, I sort of knew there were such things as Hondas and Suzukis. I saw high school girls riding them but I spent more time looking at the girls than the machines. They weren’t motorcycles. Harleys and rat BSAs were what I could afford, Triumphs were what I’d have when I got rich. They were motorcycles. Japanese motorcycles were . . . something else.

Honda and Suzuki and Yamaha and Kawasaki paid me no mind. The Cubs and Dreams and Super 90s got bigger and

more popular and more people rode them and they began winning races and setting records and so forth and suddenly they had 90 percent of the market except we purists were supposed to not like them because they had nothing but speed and reliability. No character. Peas in a pod. Tape over the name and you can’t tell ’em apart.

This may have been true, in part, at one time. I picked up the clues when I first went to Japan five years ago. We saw giant factories and teeming production lines and gleaming test centers and countless crates of bikes on their way to the rest of the world.

We didn’t see any motorcycles. Instead, there was two-wheel transportation buzzing everywhere, harried housewives and proper city gents riding newer versions of those step-through 70s. No dressers, no cafe racers, no motocross kids, no stoplight warriors. At the races 20,000 people had come by bus and train, maybe 100 on motorcycles. The factory men knew production, but not production racing. Bikes were for building and selling, but not riding.

We human beings are not creatures of the mind. Expertise isn’t enough. If the staff of this magazine was transferred intact to Woman’s Day, or World Tennis we’d last about six weeks. We know the magazine business and how to select pictures and correct spelling and meet deadlines. But we aren’t women or tennis players and we’d be producing a magazine for somebody else. We’re motorcycles nuts and we’re at our best putting out a magazine for motorcycle nuts, like us.

Enter the UJM. I think the best consumer product in the history of the world was the American V-Eight. Nothing before or since met the needs of so many people, for so long a time at such reasonable cost. Second place goes to the Japanese step-through on the same grounds. The Cubs and 90s were perfect in their> time and place. They did what they were supposed to do. They did it so well becausç the men who designed and built them understood firsthand what they were making for whom.

There was a limited market for the stepthroughs in the U.S. and Europe. There was more business to be done in larger, faster and more complicated motorcycles. The Big Four supplied the new demand'. They had the engineering know-how and the production skill and they improved the motorcycleas a machine beyond all expectations.

But they were building for somebody else. There was a translation problem. Not language. You can speak Dutch or Nor* wegian and like Harleys. I don’t speak Italian but I have a Ducati Single, all pol-' ished and on display because I think it’s the best looking Single ever made. The translation gap comes when you’re building a product for people not like you, to be used under conditions you’ve never experi* enced. You get a machine that’s all mind and no heart. Science but no soul and that’s why for a time there was such a thing as the UJM, the forgettable motorcycle.

During the past few years this has changed. Not in one great leap. At no time did we notice any major addition of emotional content. Á

Instead, we’ve gradually come to realize that the major challenge of our test" program is simply to correctly describe the test bike’s character. The facts are easy. We run the bikes at the track and with the computer and weigh them on the certified scales and double check the fac-^ tory’s specifications and so forth. We set down the lap times of the motocrossers, the quarter-mile speeds for the sports bikes, the load and fuel capacities of the touring machines and make our comments on the brakes and still, we haven’t captured the motorcycle’s soul.

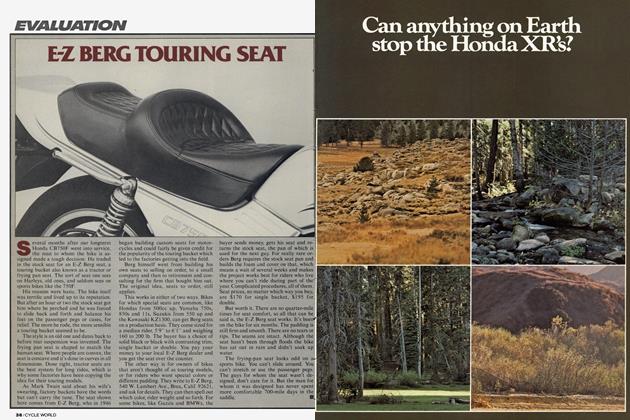

Well now, just what is this thing called1 character? It can’t be defined, or mea-, sured. Instead we know it and feel it. The closest we can come to pinning the quality down is to say how different are the models of outwardly similar size and shape. The Honda XR250 and Yamaha TT250 are as different as two four-stroke 2500^ playbikes can be. The Kawasaki GPzl 100 and Suzuki GS1100 are as close in performance as two ticks of the stopwatch, while some of us liked one and some the other and nobody was indifferent to either.

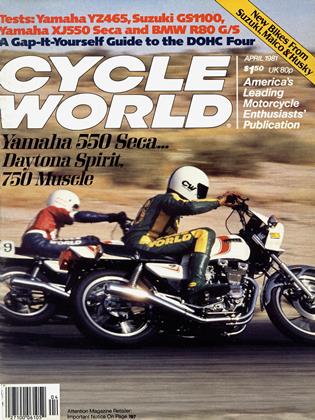

The Honda, Kawasaki and Suzuki 750 Fours are the same way. We haven’t at this* writing been on the Yamaha 750 Four, but there’s no doubt it won’t be like the other 750s. We all fell in love with the 550 Seca.

What it means is character. Japanese > motorcycles are not all alike.

How this came about began to unfold when I went to Japan last year. Another odd thing about people: Eve seen my wife every day for half our lives and I don’t understand her at all. But visit a foreign country, a very different culture a few times and right away, I’m an expert. As an old Japan hand I warned the others on the trip that they wouldn’t see motorcycles as we know them in the U.S. About that time we walked out of the hotel and hiked to the shrine and were nearly run over by all the bikes. It was a national holiday. The shrine and park were halfway along northern Japan’s version of Racer Road, a neat series of twisting mountain roads up, then another series down. Every scratcher in the district was there with his 250 or 400 Twin, fitted out with rearsets and clip-ons. They were having a wonderful time, much better than I, who had slunk to the back of the bus.

On down the road we saw proper businessmen. Riding Harleys and BMWs< There were 750 Fours and 500 Twins and dual-purpose Singles with enduro gear.

On to the races. During the Suzuka Eight-Hour I walked from the pits across to the stands and parking area.

It looked like Daytona, Assen, the Isle of Man. Motorcycles parked in rows as far as the eye could see. Riders in BelstafT jackets. Couples in his-and-her leather1 touring suits and replica racing suits. Mud-covered touring machines with the rider asleep on the grass, having ridden so long and hard he’d sleep through the race and wouldn’t care because being at Daytona, Assen, IOM or Suzuka is enough.

This is being done despite handicaps we< westerners don’t have. There is a Japan, Inc. Official policy in Japan is that bikes and cars are for sale, not home use. Fuel prices are frightful. Japan doesn’t have a highway system. There’s one toll road. No autoroutes, motorways or Interstates. There are crippling taxes, special riding tests, limits on riding downtown, on the highway. And we’ve always been told the Japanese are the most cooperative, least individualistic of people, but here they are, scraping pegs and riding dirt bikes up Mt. Fuji and mortgaging the house to buy Harleys.

Off to the factory. Out at Honda’s test^ track they rolled out the NR500. Turned out we were the first westerners, first reporters to ride the Great Red Hope. But not the first non-racers. Mr. Irimajiri, the racing wizard, did just what Lord Hesketh or Edward Turner or Willie Davidson would have done. He pulled rank and went* for a ride.

The shop apron was packed with Honda technicians. They didn’t get to ride but they’re on the team and that strange little GP bike flies their flag. If wishes were horsepower the NR500 would top out at 275 mph.

continued on page 200

continued from page 10

At the dirt proving ground one of the test riders was supposed to lead us around. Five years ago the press went so fast the factory testers retired with engine troubles invisible to the western eye. This time we can hardly keep the guy in sight.

Back at the track. I wandered down pit row, away from the gleaming factory bikes and into the clubmen ranks. There’s a Yamaha motocross engine, a 400, crammed into a road race frame. No, it’s not fast, they sign-language, but it’s fast enough to make the field and it’s the only engine we had, and if it holds together, who knows? (Sorry to say we never learned how the engine would hold up. The frame broke. But they weren’t the slowest bike there.)

Another surprise. A pit with twice as many machines as it has room for. Freaky machines; cobbled frames painted by brush, suspension systems I can’t describe, engines assembled from cast-off parts, a practice I used to indulge in myself which is how I know the signs.

It’s Honda R&D. Not the factory team. Sort of the opposite. These are the designers and draftsmen and accountants and clerks, no rank, no serial numbers. All the nutball racing fans have been saving and scrimping and designing their own racers. They’re out there just because they like to build engines and try ideas the supervisors brushed off and to ride as fast and well as they can. I am reminded of the European enduro crazies, the whacky Dutchmen and Germans and Italians who show up with leading-link front ends, center-point steering, screwball stuff like that except that every so often some inventor comes up with a system that we know as the DeCarbon shock, or Mono-shock rear suspension. I think of the English drag racers with supercharged Vincents, the road racers flogging BSA Bantams—all-time classic definition of The Hopeless Case— to breathtaking speeds.

I got it. This is where the character comes from. The men behind the Seca 550, GS 1100, GPz and CR450 are no longer working on a translated order for a motorcycles for some rider far away. The Honda 750 isn’t like the Kawasaki 750 or the Suzuki 750 or the Yamaha 750 because each is the product of different inputs from men with their own private enthusiasms. They are building for their friends and neighbors and fellow club members and by extension for bikers all around the world. They are building for fools like us.

And they’re doing it right because they are fools like us.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue