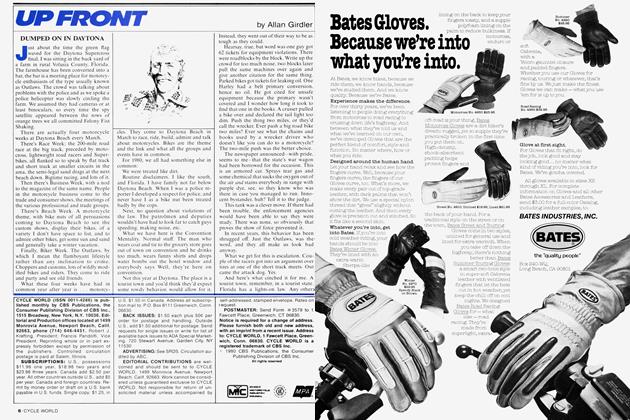

Nailing It Down

Picking the Right Lock or Alarm Requires More Than a Look at the Box.

Peter Egan

Anyone who ever parked a motorcycle on a dark street and walked off to a five-hour double feature knows the feeling. You look back over your shoulder one last time and think, “Nice Bike. I hope it's there when I get back.” All through the movie people around you laugh and have a good time, while you remain mildly troubled, remembering how vulnerable your bike looked sitting by the curb. Others enjoy life, while you fret and mentally calculate the cash value of all those trick parts and accessories. An uncomfortable feeling, and one case where a touch of paranoia is justified.

Some 50,000 motorcycles vanished from the streets and alleys of America last year, destined to reappear in the hands of satisfied new owners, or as discount parts. In sheer numbers, big displacement Japanese multis won Most Ripped-Off honors, led by the Honda 750 in its many permutations. No brand or model, however, proved immune to theft. (We know of a case where a Wards 125 was stolen, though later found less than a mile away.) Compared with cars, the recovery rate on stolen bikes is poor. In states where police are given money and encouragement to track down motorcycles, chances are about 50-50 a missing bike will be found; in> other states the odds are less heartening. And half of all recovered cycles come home damaged or stripped.

In other words, there is just cause for worry. Bad guys are not a product of the imagination; they are really out there. Shifty operators abound.

Back in the days when men were men and horse thieves were hanged until proven innocent, people were more cavalier about securing their transportation. They threw a couple of leather straps around a wood rail and went about their business, whistling “Buffalo Gals” or “Camptown Races.” We’re more civilized now. We have theft insurance and security systems. While a good insurance policy will ease the sting of motorcycle loss and give the victim a temporary sense of wellbeing, there are still some problems. The great tradition of collective responsibility, it turns out, has you and your friends paying quarterly installments on all the world’s stolen bikes. And they are not cheap. The sting returns at premium time. Even if you can afford and collect insurance, Blue Book retail is often a sad substitute for a favorite motorcycle. Some machines, like faded blue jeans and comfortable old shoes, are irreplaceable. Also, few insurance policies pay you for walking home at two in the morning. So unless your cycle had a bad rod knock just off warranty, there’s no bright side to having it stolen.

Fortunately, Science now offers a wide selection of gear designed to make motorcycle theft annoying or inconvenient, if not always impossible. Ranging in complexity from medieval to high-tech, the current lineup includes padlocks, chains, cables, giant U-bolts, brake locks, buzzers, horns, and pagers. Broken down into their respective functions, anti-theft devices fall into three categories: (1) those that prevent a bike from being rolled or lifted; (2) those of the whoopee-cushion school, which make loud, embarrassing noises and draw attention to themselves; and (3) others designed to inform the owner, discreetly, that his machine is being fiddled with.

We decided to procure a representative sampling of the crimestoppers on the market, live with them a while, then weigh their various merits and drawbacks; i.e., cost, convenience, and likely effectiveness.

That last one was the clincher. How do you test the effectiveness of an anti-theft rig without exposing it to the skills of a bona fide motorcycle salvage artist? And what limits do you set? Obviously, if a thief has enough time and equipment, any motorcycle can be stolen. Rumors of outrageous tools of theft float through motorcycle lore like bad dreams; stories of trucks with hydraulic cranes that lift bikes away in the night, bolt cutters with nine-foot handles, and so on. And on a more primitive level you’ve got four guys with plenty of tattoos and toothpicks who can heave a full-dress Electra Glide right into the back of a pickup while you search for dimes in a nearby phone booth.

The problem is, not all motorcycle thieves are created equal; they vary a lot in skill and the ability to premeditate. The joyriding kid who finds a key in the ignition switch may ignore a bike with locked forks and a chain through the spokes, whereas a pro can smash a fork lock and snap a chain in seconds. There is no single test to determine whether a piece of hardware will save your motorcycle. A good design will simply discourage a larger segment of the thieving public. How successfully you convert your bike to an immovable object depends not only on which lock and/or alarm you choose, but on the expertise of the person coveting your goods.

With those variables in mind, we installed, used, and later tried to disarm or destroy a variety of security systems now on the market. For implements of destruction we kept it simple, using bolt cutters, pliers, hacksaws, chisels and hammers. Torches, power tools, and other 007 exotica were judged too noisy or flashy for the average thief (if there is such a person) and unbefitting the practical nature of this survey. We wanted to know: First, does the thing work? Does it really latch, honk, transmit, or whatever it’s supposed to do? Second, is it easy to use or such a hassle you can’t be bothered? A good design doesn’t discourage use. And. third, is there any chance it will keep a motorcycle from being stolen? Or can it be rendered useless by a tech editor or a child with hand tools? Cost is mentioned too, though that is a problem of personal judgment and income.

Here’s what we found:

Campbell Padlock

Campbell Chain Co.

399 E. Market St.

York, Pa. 17402

Commencing with the simplest things, we tried a heavy-duty padlock made by the Campbell Chain Co. The lock has a solid stainless steel body and a 7/16 x 4-inch shackle with the word “Hardened” stamped on it.

Padlocks—even those with long shanks— are not very useful by themselves on most motorcycles. Harleys generally have fork brackets designed to accept a padlock, but most bikes have no good place to attach one. A padlock can be hooked over the chain or through the sprockets or fender supports on certain models, but only at the risk of motorcycle damage. It wouldn’t do to forget and take off with a lock on the chain; hard on the countershaft sprocket.

The alternative is to get a good chain or cable loop. Choices of chain are endless, and you can choose one from whatever^ weight/cost bracket suits your needs. There are some truly massive nauticalstyle chains available, but most cyclists prefer one that can be carried easily (or worn, if you’re into that sort of thing). We used the padlock on an ACCO Guardian chain, bought through Honda of Mineolh for $18.95. The chain is made of %-in. hardened steel (no one advertises softened* steel in the lock business), is 5 ft. long and vinyl coated. The vinyl has worn away because the chain has been in daily use by a staff member, but the links themselves proved impossible to break or saw. +-

Not so with the padlock, unfortunately. Our bolt cutters got a good grip on the'1 curve of the shank and neatly severed the lock, right through the “Hardened.” The lock did appear to be surface hardened, however; the hacksaw skated around and refused to bite anywhere on the shank oj body.

The best thing about chains and locks is* that they look mean and forbidding, and, if they are large and heavy, suggest the same qualities in their absent owners. Whether they work or not depends on the quality of the weakest link, either lock or chain. Take your bolt cutters when you go shopping.

Chains also have the advantage of being available in any length deemed necessary to wrap up vital parts of a motorcycle, and they can be stored compactly. A canvas bag is a good idea for bikes without some kind of luggage. Chains don’t stay put very well under a bungee, and dangling ends., make a nasty combination with drive chains and rear wheels. >

Maxim 75-11 Cable Lock

Maxim Lock Co.

Chicago, 111. 60618 Cost: $42.95

The Maxim 75-11 is a 6-ft. length of half in. tempered steel cable, coated with black vinyl and held together at its ends by a lock body of 1 % in. cold rolled steel. Halves of the body are secured by a “Seven Tumbler Tubular Key Lock with 800,000 Possible Key Combinations.” The same company also makes a Maxim 75-1 with five-eighths in. cable, but the larger lock (1% in.) prevented it from fitting through cast wheel spokes on some of our test bikes. The smaller model is a foot shorter and easier to roll up and stow.

The Maxim 11 can be zipped into a tank bag, or tied down to the passenger seat with a bungee cord. The cable is long enough to pass through the rear wheel, frame, and over the seat. It will also link the bike to a small tree, lamp post, etc., or to another motorcycle.

Hardware on the Maxim works fine, once you get the hang of lining up the bolt cutaway with the holes in the lock body. Its only drawback (or advantage) in daily use is that you feel compelled to use it even for quick stops. Otherwise somebody might see the neatly coiled cable sitting under your bungee cord and steal it. Lock theft at $42.95 being no laughing matter, the cable went on—grudgingly—at gas station pit stops. Stop & Go stores, and fast food joints. Which is the whole idea, of course. No natural law says your bike can’t be stolen just because you won’t be gone very long.

Because the value of any cable is in the collective strength of its individual strands, we picked on them a few at a time. Which worked pretty well. Our war surplus bolt cutters from Taiwan had no trouble chewing all the way through in about one minute. The cable resisted instant clipping because of its springiness. A hacksaw sliced through the Maxim in two minutes of noisy, sustained effort.

The lock itself was unmoved by our best destructive efforts; no amount of pounding, chiseling, or splitting its halves with a wedge had any effect.

Because the Maxim can be cut, its main value is in preventing the roll-away or joyride theft. Equipment is needed to snap the cable, so those without tools will leave the bike (or at least the frame) alone. Parking the cycle in a public place should afford some protection from all but the most brazen bolt cutter and hacksaw owners. Advantages? The cable can remain locked around a pole or rail at a daily parking spot so you don’t have to carry it with you, and one lock will work for two motorcycles. Used with an alarm, the cable will also save the casual thief the trouble of tripping an alarm before he discovers the bike is rigged.

Kryptonite

Kryptonite Bike Lock Corp.

95 Freeport St.

Boston, Mass. 02122 Price: $39.95

The Kryptonite is essentially a 16-in. Ubolt of hardened steel with a 6-in. shackle that locks the open end. The steel is covered with black vinyl to protect the4 motorcycle, and it locks with the same tubular-style key found on all the other locks we tested. The U-bar is long enough to pass through both rear shocks and the rear wheel, front fork and wheel, or fronj the frame to a fence or pole.

First impression of the Kryptonite that it feels like a big chunk of metal to carry around on a motorcycle. It weighs only 3.3 lb., however, and will fit into the (padded) bottom of most tank bags or across the passenger seat if you travel solq. Kryptonite is supposedly the material that gave Superman fits, and we didn’t faremuch better with it. We were unable to break, bend, or saw the lock. We tried filing off the outer surface before sawing and got nothing but toothless hacksaw blades for our effort. Bolt cutters made no

-£

impression on the steel shaft or lock, nor did twisting a 5-ft. lever through the Kryp-„ tonite while it was locked in a vise. We chilled the steel with compressed Freon, then hammered and twisted. Nothing. Someone somewhere probably knows how to break the thing, but we couldn’t. A cutting torch would be a good remedy for lost key.

Like all locks, the Kryptonite protects only the pieces it encircles, and, like cable, must be used to keep people from walking off with it. Other than that, and having to carry it around, the Kryptonite has few disadvantages.

Stop & Lock

Stop & Lock Co.

411 Tamal Plaza, Box 533 Çorte Madera, Calif. 94925 Price: $49.95

r A more compact variation on the rollprevention theme is the Stop & Lock. This is a mechanical device, mounted at the rear axle, which works by holding the rear brake fully applied or by sliding a dead bolt through holes in the disc brake rotor hub, depending on the bike’s design. We installed the dead bolt model on a Suzuki GS750L. On a GS the Stop & Lock body replaces the stock brake caliper arm, the body being a nicely machined piece of aluminum. When parking, the rider simply takes the hardened steel dead bolt out oYhis pocket, slides it through a hole in the fiew caliper arm, and engages a hole in the brake rotor. A lock in the aluminum case pins the dead bolt so it can’t be removed. On leaving, the owner unlocks and pockets the bolt and rides off. The only equipment carried is a set of keys and a 3 in. long, five£ighths in. steel bolt (bound to resurrect all those old BMW ignition key jokes, “Are you happy to see me, or do you own a Stop & Lock?”).

Installation time on the Stop & Lock will vary from one motorcycle model to another. Directions for the Suzuki 750 /£rsion recommended that the exhaust sys:em be dropped out of the way so the rear ixle could be slid back to remove and> replace the caliper arm. On the L model, however, it was simpler to detach the upper shock mounts and drop the swing arm below the pipes. In other words, installation was easier than rear wheel removal on the GS—but the lock is nearly impossible for a thief to dismantle because it cannot be removed once the deadbolt is in position.

Contrary to a commonly expressed fear, there is no way the lock can suddenly drop into place on the highway, bringing the bike to a smoking halt; the locking bolt has to be removed for the cycle to roll.

The Stop & Lock keeps your rear wheel from turning; simple as that. Any thief without the means to lift the bike or put the rear end on rollers will have to leave the motorcycle where it sits. We were unable to break the lock; the dead bolt could not be hammered or twisted out, and with the bolt in place the lock body was immovable. We tried some full-rev burnouts to see if the bolt (or rear brake hub) would weaken or snap, but merely tortured the clutch and killed the engine.

A strong point of the lock is its simplicity and convenience; it demands no hauling of cumbersome hardware. On the minus side, it does allow a motorcycle to be stripped down to nothing but a frame, rear wheel, and Stop & Lock. Also, there is no way to secure the bike to a solid object or other motorcycle. But for its intended purpose-preventing the machine from being rolled or ridden away—the Stop & Lock works.

DAI 1000

Product Development Corp.

740D Sierra Vista Avenue Mountain View, Calif. 94043 Price: $59.95

Moving from nuts and bolts to electronic wizardry, we have the DAI 1000. The DAI is a sound-sensitive alarm system. It consists of a microphone, horn, and control unit, all linked together by short sections of wire and connected to the motorcycle battery. The microphone is embedded in a rubber block with a concave cutaway, so that it can be tie-wrapped to a motorcycle frame with the mike facing inward. The horn comes as a compact, inch-wide cylinder with its own strap and can be attached anywhere beneath the seat, tank or sidecovers. We found space for it on the Suzuki 750 (well on its way to becoming the most theft-proof motorcycle on earth) beneath the seat, next to the airbox.

The control unit is a little smaller than a deck of cards and has to be mounted where you—and no one else—can get to the on-off switch. Under the seat or in a locked compartment is best. It helps if you can get to it quickly, because clumsy fiddling with keys may set it off. The Suzuki had space for it beneath the seat, so we stuck it to the rear fender with the two-sided backing tape provided.

The control box has an on-off switch and two adjusting screws, one for sound sensitivity and the other for setting time delay. The latter gives you anywhere from eight to 20 sec. to slam the seat, remove the keys, and getthehellouttathere before the alarm wakes up.

The sensitivity control offers a wide range of responsiveness to noise; at its highest setting it will beep like crazy with no more provocation than the nearby rustle of a fat lady in nylons. Set on low, you can drop it off a six-story building. It takes a while to zero in on the appropriate adjustment. We finally arrived at a setting which allowed the seat to be opened— carefully—to defuse the alarm without tripping it, yet the horn would sound if the sidestand were folded up or the forks swung full-lock. The alarm could be set off by loud shouting at very close range (it liked “Hello!” best; was unmoved by expletives). Other noises in the room; dropped screwdriver, running air compressor, etc. had no effect.

The sensing unit was selective in responding to frame noise, preferring the hard, mechanical click or tap to softer sounds, such as sitting on the seat or rolling the motorcycle down the street. Starting the engine set it off every time.

Unfortunately, we had trouble getting a consistent sensitivity level. Heavy breathing might set the alarm off in the evening, but slightly more commotion was needed the next morning. Except for this latitude of operation the alarm performed reliably and could easily be heard from inside most buildings (office, house) providing no Led Zeppelin albums were played.

Snipping wires on an alarm is a less fair test of its design than, say, cutting a cable or padlock which sit out for everyone to see. The elements of surprise and subsequent dismay are the most important virtues in any alarm system. It is possible, however, to remove sidecovers and snip battery ground wires on most bikes, thereby cutting power to the alarm, without making much noise. We were able to do it on the DAI 1000, but then we knew it was there. With the unit well hidden beneath the seat, most people won’t.

Cobra

Micronics International, Inc.

P.O. Box 6319 Anaheim, Calif. 92804 Prices: Alarm, $59.95; Pager, $149.95; Purchased together, $199.95

The Cobra is a motion-sensitive alarm that trips its horn when a small ball bearing is tipped or rolled across the circuitry in. its control box. A transmitter and pager are available as an add-on, so if somebody jostles your bike in the parking lot or garage, a high-pitched beep from your pocket lets you know. What you do after that is your problem.

The basic alarm and horn setup is quick and easy to install. On the Suzuki 750 we attached the sensing unit to the side of the battery with the stock rubber battery strap. The horn bolted neatly under an airbox bracket. The transmitter, which we mounted inside the fiberglass tailpiece* took longer to install because wires on the alarm circuit had to be tapped into and no connectors were provided. No big thing, unless it’s Sunday and the hardware store is closed.

continued on page 116

continued from page 52

The alarm is set by riding the motorcycle, or turning the ignition switch on for at least 10 sec. and shutting it off again. When you park the bike and switch the ignition off, the sensing unit waits 60 sec. and then arms itself. If the cycle is shaken or moved any time after that, the alarm goes off. It then beeps loudly for 20 sec. and resets. Any further disturbance will trip it again. The pager continues to beep until manually shut off. The whole system can be disarmed by quickly flicking the ignition on and off once.

A wire-embedded-in-tape antenna is provided for the transmitter. The company recommends that the antenna be installed as far from the metallic mass of the bike as possible; i.e., around the inside of a fairing or—if there is no fairing—inside the top seam of the seat. The ideal, for long-range transmission, is to connect the transmitter to a CB antenna, and wired jacks are provided for that purpose.

We taped the factory-supplied wire antenna around the inside of a full touring fairing and found the range to be very good. The alarm tripped the pager from a quarter mile away, over buildings and through walls. Because no competent motorcyclist should ever travel more than a quarter mile on foot, that transmission radius seemed adequate for all occasions. Using a CB antenna should push the range beyond the limits of human endurance.

The alarm detected all attempts to jostle or move the Suzuki, and went off'when we removed the sidecovers or opened the seat. The motorcycle could be used normally with no thought given to the alarm system. All switching is done with the ignition key, so there are no games with seat latches or secret compartments.

The pager seems a worthwhile option for anyone using an alarm. The public, jaded no doubt by too many Corvettes bleating away in supermarket parking lots, does not respond with much alacrity to pulsing horns. We set off'both the DAI and the Cobra in all kinds of places during our test without arousing curiosity. No angry mobs of villagers armed with torches and pitchforks swarmed to our rescue. No one asked just what we thought we were doing. The local Fahrenheit 451 police helicopter passed benignly overhead without so much as a token swoop. Unless you hear the alarm yourself, don’t expect outside help. And beyond hearing distance, only a pager will put you on alert.

The trouble with pagers, of course, is that they force you to do something. There you are, sleeping one off, when a voice says, “Wake up. dear. There’s someone in the garage messing with your bike.” Time for action. You can either call the police or stroll down to the garage yourself. “Say, that’s a nice motorcycle,” you tell the intruder as you calmly slip some birdshot into your favorite Belgian mantlepiece. “Is it yours?”

And so on. Either way, you at least know something is amiss. (By way of mention without comment, the people at Cobra tell us many Harley owners have written to say they would like an optional horn switch that allows only the pager to work, so they can catch meddlers red-handed. In the same questionnaire, most Honda owners preferred that both horn and pager function.)

Other than high cost, a disadvantage of sound and radio alarms is that they rely on people for physical restraint of the motorcycle; if no one intercedes, the machine can be ridden or carried away. Locks and chains, on the other hand, make a cycle hard to move but offer no protection from stripping or vandalism. The answer, for the truly security conscious, is probably a combination of alarm and lock. If the bike is stolen anyway, there is satisfaction in knowing you’ve been hit by a pro, rather than losing your motorcycle to a common bungler. You tried.

Beyond security systems, one or two other tricks are worth considering. Police departments concur that, while alarms and hardware are fine, there is no substitute for keeping a motorcycle out of sight. A bike that sits on the same front lawn every night is noticed. It becomes a minor landmark for people who cruise. Hiding it from view in a garage, hallway, or behind a fence will do wonders for reducing the drive-by trade. Even a cycle cover is better than nothing, because it discourages identification of a sought-after model. Throw a cover over a Z-l and it looks just like a fully-chopped Grin'dlay-Peerless with mudflaps.

If alarm technology and secret hiding spots fail, the best hope of recovery lies in proper vehicle ID. An owner can greatly improve chances a bike will be identified and returned by engraving Social Security or driver’s license numbers on every possible piece of the machine. That way a motorcycle isn’t rendered anonymous when the frame and engine numbers are gound off with an emery stone. And, down at Headquarters, you are spared trying to identify your blue 750 by the amount of chain lube on the rear wheel.

One last theft deterrent should not be overlooked, because it is probably the cheapest. It eliminates all concern with locks, alarms, vehicle ID, and recovery; makes worry and anxiety a thing of the past. It was suggested during this test that the best theft prevention is simply to own a motorcycle nobody else wants; a bike with such abysmal performance and so little redeeming aesthetic value, that even the lowest, most corrupt elements of society are loath to deal with it; a motorcycle dented by the tips of 10 ft. poles. While we’ve done no empirical testing, our managing editor has used this system for years, and it seems to work very well. 9