Above all, Yamaha is secretive. When a reporter visiting the factory in Japan asked Mr. N. Hata, director of motorcycle engineering, about Kenny Roberts’ aluminum-framed Grand Prix racebike, Mr. Hata only smiled. He wouldn’t discuss the bike, wouldn’t even confirm its existence.

Mr. Hata did say that the reason Yamaha crushes works racebikes at the end of each season is to preserve secrecy. The company doesn’t want technology incorporated into racers to fall into the hands of anybody.

The Yamaha used in 1978 by Kenny Roberts to become the first American 500cc World Champion didn't end up in a museum, but instead was destroyed to fulfill the factory’s desire to hold technological cards close to the vest.

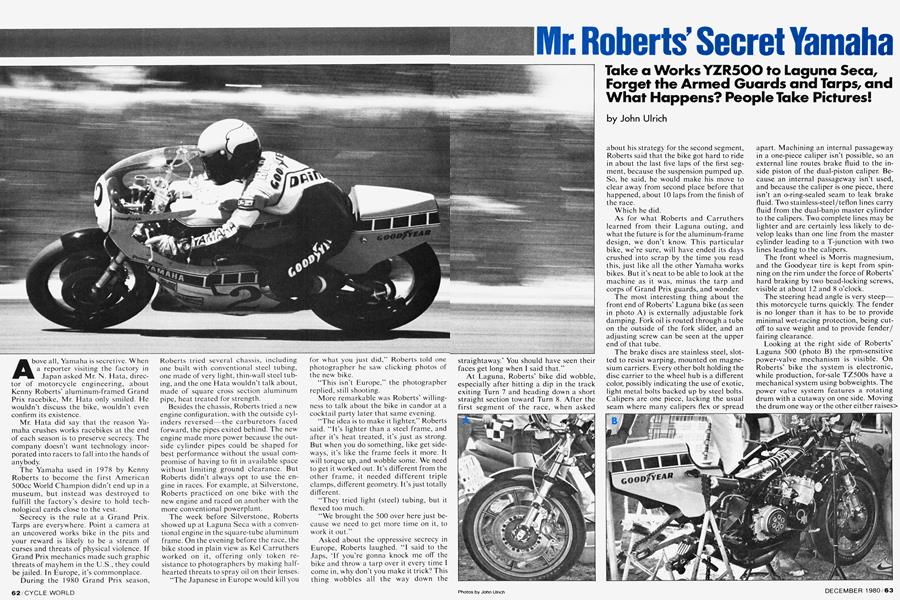

Secrecy is the rule at a Grand Prix. Tarps are everywhere. Point a camera at an uncovered works bike in the pits and your reward is likely to be a stream of curses and threats of physical violence. If Grand Prix mechanics made such graphic threats of mayhem in the U.S., they could be jailed. In Europe, it’s commonplace. During the 1980 Grand Prix season, Roberts tried several chassis, including one built with conventional steel tubing, one made of very light, thin-wall steel tubing, and the one Hata wouldn’t talk about, made of square cross section aluminum pipe, heat treated for strength.

Besides the chassis, Roberts tried a new engine configuration, with the outside cylinders reversed—the carburetors faced forward, the pipes exited behind. The new engine made more power because the outside cylinder pipes could be shaped for best performance without the usual compromise of having to fit in available space without limiting ground clearance. But Roberts didn’t always opt to use the engine in races. For example, at Silverstone, Roberts practiced on one bike with the new engine and raced on another with the more conventional powerplant.

The week before Silverstone, Roberts showed up at Laguna Seca with a conventional engine in the square-tube aluminum frame. On the evening before the race, the bike stood in plain view as Kel Carruthers worked on it, offering only token resistance to photographers by making halfhearted threats to spray oil on their lenses.

“The Japanese in Europe would kill you for what you just did,” Roberts told one photographer he saw clicking photos of the new bike.

“This isn’t Europe,’’ the photographer replied, still shooting.

More remarkable was Roberts’ willingness to talk about the bike in candor at a cocktail party later that same evening.

“The idea is to make it lighter,’’ Roberts said. “It’s lighter than a steel frame, and after it’s heat treated, it’s just as strong. But when you do something, like get sideways, it’s like the frame feels it more. It will torque up, and wobble some. We need to get it worked out. It’s different from the other frame, it needed different triple clamps, different geometry. It’s just totally different.

“They tried light (steel) tubing, but it flexed too much.

“We brought the 500 over here just because we need to get more time on it, to work it out."

Asked about the oppressive secrecy in Europe, Roberts laughed. “I said to the Japs, ‘If you’re gonna knock me off the bike and throw a tarp over it every time I come in, why don’t you make it trick? This thing wobbles all the way down the straightaway.’ You should have seen their faces get long when I said that.”

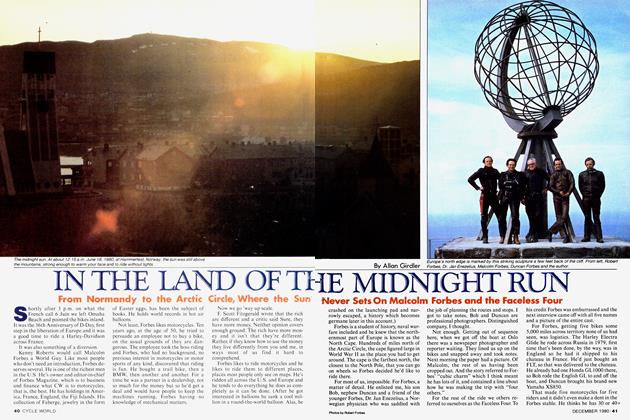

Mr. Roberts' Secret Yamaha

Take a Works YZR500 to Laguna Seca, Forget the Armed Guards and Tarps, and What Happens? People Take Pictures!

YZR500

John Ulrich

At Laguna, Roberts’ bike did wobble, especially after hitting a dip in the track exiting Turn 7 and heading down a short straight section toward Turn 8. After the first segment of the race, when asked about his strategy for the second segment, Roberts said that the bike got hard to ride in about the last five laps of the first segment, because the suspension pumped up. So, he said, he would make his move to clear away from second place before that happened, about 10 laps from the finish of the race.

Which he did.

As for what Roberts and Carruthers learned from their Laguna outing, and what the future is for the aluminum-frame design, we don’t know. This particular bike, we’re sure, will have ended its days crushed into scrap by the time you read this, just like all the other Yamaha works bikes. But it’s neat to be able to look at the machine as it was, minus the tarp and corps of Grand Prix guards, and wonder.

The most interesting thing about the front end of Roberts’ Laguna bike (as seen in photo A) is externally adjustable fork damping. Fork oil is routed through a tube on the outside of the fork slider, and an adjusting screw can be seen at the upper end of that tube.

The brake discs are stainless steel, slotted to resist warping, mounted on magnesium carriers. Every other bolt holding the disc carrier to the wheel hub is a different color, possibly indicating the use of exotic, light metal bolts backed up by steel bolts. Calipers are one piece, lacking the usual seam where many calipers flex or spread apart. Machining an internal passageway in a one-piece caliper isn’t possible, so an external line routes brake fluid to the inside piston of the dual-piston caliper. Because an internal passageway isn’t used, and because the caliper is one piece, there isn’t an o-ring-sealed seam to leak brake fluid. Two stainless-steel/teflon lines carry fluid from the dual-banjo master cylinder to the calipers. Two complete lines may be lighter and are certainly less likely to develop leaks than one line from the master cylinder leading to a T-junction with two lines leading to the calipers.

The front wheel is Morris magnesium, and the Goodyear tire is kept from spinning on the rim under the force of Roberts’ hard braking by two bead-locking screws, visible at about 12 and 8 o’clock.

The steering head angle is very steep— this motorcycle turns quickly. The fender is no longer than it has to be to provide minimal wet-racing protection, being cutoff to save weight and to provide fender/ fairing clearance.

Looking at the right side of Roberts’ Laguna 500 (photo B) the rpm-sensitive power-valve mechanism is visible. On Roberts’ bike the system is electronic, while production, for-sale TZ500s have a mechanical system using bobweights. The power valve system features a rotating drum with a cutaway on one side. Moving the drum one way or the other either raises> or lowers the exhaust port height of the cylinder. By lowering the exhaust port height the engine makes more power at low rpm, while raising the exhaust port height makes the engine produce more power at high rpm. So the power valve system gives the best of both worlds—lowend power to come off the turns, and maximum high-rpm power to fly down the straights. The power valve system uses push-and-pull cables just like the ones seen on banks of slide-throttle carburetors on multi-cylinder street bikes. A close look at the cable drum on the cylinders shows that two ranges of operation can be selected, probably to allow tuning for specific tracks.

There have been rumors that Yamaha is experimenting with the power valve system on the intake ports as well, but Roberts’ bike at Laguna had conventional piston-port induction—no power valves, and no reed valves as used on the TZ750.

On the left side of the front wheel, Carruthers used two screws to hold the tire bead. On the right, he used three.

The tach is driven off the clutch, with asbestos wrapped around the cable at one point to keep it from being burned on the exhaust pipe. The aluminum plate located at the end of the crankcase probably holds the fairing off the engine cases, or keeps it from contacting the pipe.

Look at the right footpeg. Did it acquire that radical bevel from Roberts dragging it as it folds up, or was it made that way?

The rear brake caliper is aluminum, two piece, off an early model OW31 TZ750.

In photo C it becomes clear why one racer looked long and hard at Roberts’ bike, shook his head and walked away muttering “It’s hard to find a steel part on that thing.”

Note the fairing mounts. Aluminum. The clutch housing screws? Titanium. Controls? Aluminum.

Of course there is the usual trickery. The carburetors are magnesium-bodied Mikunis with short velocity stacks and the Mikuni equivalent of the power jet—an enrichening circuit which comes into play at 3/4-full throttle, depending upon the length of the circuit tube.

After pulling the clutch, Carruthers can remove the transmission shafts through the side of the cases. That changes transmission work from a split-the-cases ordeal into a 15-20 min. operation. That makes it feasible for Roberts to come in from a practice session, tell Carruthers that he’d like to try a slightly different second-gear ratio, and then make the next practice on the same bike.

The bulge on the side of the outside cylinder is a huge transfer port. The same thing is seen in the latest TZ125s and TZ250s, and frees engine tuning from the old constraint of the outside wall of the cylinder casting.

The monoshock has a short spring, and preload can be adjusted by rotating a threaded collar along the threaded body of the shock. Damping may also be adjustable, judging by the screws on the side of the body, but we’re not sure.

Note the brake pedal and the swing arm pivot shaft—they’re hollow to save weight.

The shift pedal on the left side of the bike (photo D) is drilled, too, and the linkage allows for pedal height adjustment as well. The countershaft sprocket has the usual swiss-cheese (lots of holes) treatment, and the countershaft itself is dished at the end of save a few ounces.

You can bet that the ignition system used isn’t anything like the system seen on TZs for sale, and the radiator looks bigger than the ones found on production TZ750s.

The exhaust pipes have very fat midsections, but the number four cylinder pipe must be dented here and there to fit over the transmission and under the frame rails and exit on the right side, all in the interests of ground clearance.

Photo E shows a large reinforcing section between the upper and lower rails of the bike’s swing arm, illustrates how the exhaust pipes exit, and gives the general idea of the view everybody else usually gets of Roberts. Just to remind everybody who’s up front, the tailpiece carries— What else?—a number one. (3