LAGUNA SECA

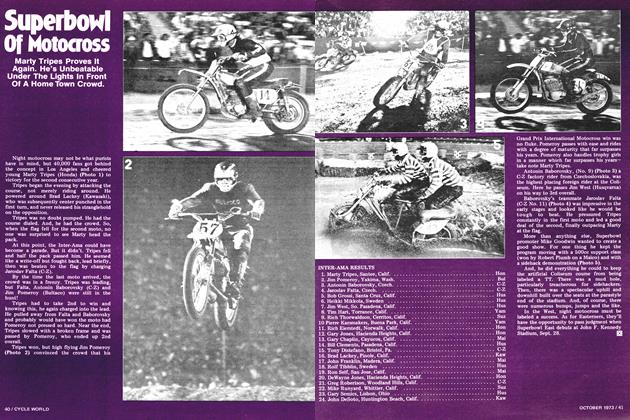

When King Kenny Roberts Comes Home To Play, No One Can Stand In His Way

John Ulrich

Formula One

"It’s easy to forget just how good Kenny Roberts really is,” a reporter confessed to Ken Clark, Yamaha’s National Racing Manager.

“The thing people don’t realize,” replied Clark, “is that he’s getting better. It isn’t like he’s hit a plateau or anything, he’s actually improving all the time.”

Kenny Roberts is the reigning 500cc World Champion. He spends most of his time racing in Europe, so it’s easy for someone in the United States to get the idea that maybe somebody will beat Roberts when he returns to the U.S.

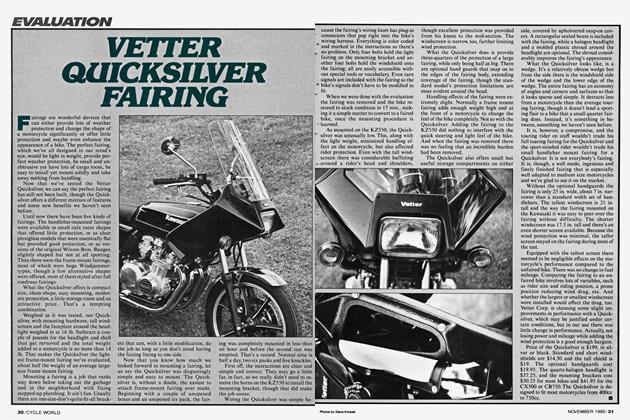

Somebody with something to prove, somebody like Fast Freddie Spencer on Erv Kanemoto’s TZ750.

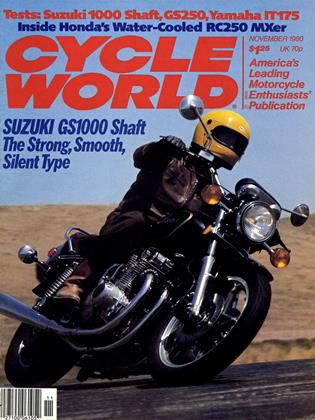

Kenny Roberts returned to the United States for the Laguna Seca Formula One round of the Winston Pro Series, a race sponsored by Champion Spark Plugs. Formula One rules allow 750cc two-strokes with intake.restrictors, 1025cc anythinggoes-except-supercharging four-strokes, and unrestricted 500cc two-strokes. Roberts brought with him a YZR500 complete with an aluminum frame made of square cross-section tubing, exotica the likes of which had never graced America before.

Spencer didn’t beat Roberts.

It was a runaway.

For anybody harboring the belief that Kenny Roberts could be beaten at Laguna Seca this year, Roberts’ homecoming demonstration was like being shaken out of a deep sleep and slapped across the face with a dead mackerel.

It was impossible not to notice how good Kenny Roberts really is.

* * *

In all fairness, young Mr. Spencer was at a disadvantage. His Kanemoto Yamaha had 250cc of engine displacement on Roberts’ YZR500, but it also weighed about 65 lb. more.

It was easy to see where the weight was lost from Roberts’ 500—the frame was the main thing, square aluminum rails * weighing a bunch less than equally-strong steel tubing. Beyond that, it was difficult to find a steel part on the motorcycle. Aluminum, magnesium, titanium parts were everywhere. A factory bike loses its pounds in even more subtle ways than replacing steel bolts with titanium or aluminum bolts. Like having a thinner, lighter, more expensive fairing. Or building a fuel Hank made of thinner aluminum sheet than production TZs.

Still, Freddie qualified second fastest, behind Roberts, at 1:08.535. Roberts had the pole position, qualifying first at 1:08.141.

It wasn’t obvious yet, but Roberts had another advantage over Freddie.

A pyschological advantage.

The advantage of having been battlehardened in the GP wars, racing on the edge at what one observer tagged “the extreme level.” Roberts fights for every GP win he gets, and like serious contender Randy Mamola (who wasn’t racing at Laguna under orders from Suzuki GB, the English not being willing to risk Randy’s excellent position in the World Championship chase in an unimportant colonial race) is always looking for any advantage he can get.

Watching Roberts race in Europe is like seeing a man fighting for his life . . . and sometimes qualifying seventh anyway. Racing Grand Prix is 100% business, no foolin’ around, everything counts on this race—or the next one, which is often only one week away. The strain of having to be at 100% week after week hardens and hones a rider.

Freddie Spencer is obviously good. He has established himself as being the fastest American regularly competing in American races.

But while Roberts and Mamola constantly race on the edge, Spencer often easily goes faster than the guys he has to race against in the U.S., as seen at Daytona 1980.

In Europe earlier this year, Roberts told some friends how much faster his new Grand Prix Yamaha was, a bike with the two outside cylinders turned around with the exhaust pipes exiting rearward and the carburetors facing forward.

But Trevor Tilbury, one of Roberts’ mechanics, expressed his doubts, pointing out that Roberts won three Grands Prix in quick order on his older bike—the machine he brought with him to Laguna— while he hadn’t done so well on the new bike.

An observer asked Tilbury if Roberts had tested the bikes back to back. “In that first half of the race,” Spencer would say later, “I wasn’t pushing as hard as I could, and he wasn’t pushing as hard as he could. I was kind of waiting to see how things went, then I was gonna try to get around him and run it up. But when we started pushing a little bit, I couldn’t even accelerate hard off the turn with it. The suspension was hopping around and it chewed up the tire so bad, got the tire much hotter. It was those closing laps when somebody would have to take a stab (at winning), and as it was, there was nothing I could do.”

No, answered Tilbury. Kenny doesn’t like to test different bikes back to back.

They’re both 500s, thought the ob-r server, yet Roberts doesn’t like to test them back to back. The guy must run at the limit all the time, marveled the ob-, server, because anything that is a little different might give him some trouble, maybe unload him. Maybe not at a certain level of riding, but at the extreme level.

As Kenny himself said, 500 GP is about guys who can ride out of control, yet under control.

On the edge.

* * *

Coming to California for Laguna Seca must have been a big load off Roberts’ shoulders. At Laguna Seca he had maybe one guy to race against—Freddie Spencer.

At Laguna, any man who could beat Roberts would have his fame and fortune" assured.

At Laguna, Kenny Roberts was on vacation.

* * *

Wes Cooley qualified third fastest, turning 1:10.441 on his Yoshimura Suzuki GS1000. Newcomer Nick Richichr* (1:10.594), Gennady Luibimsky (1:10.619) and John Bettencourt

(1:10.995) were the only others in the 1:10 qualifying range.

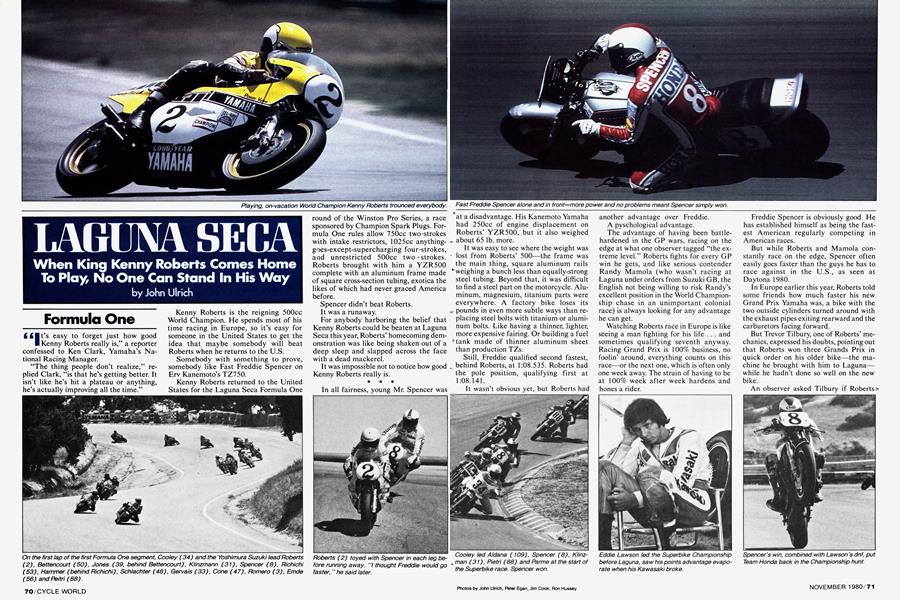

Always a fast starter on his big four-, stroke, Cooley jumped into the lead off the start, chased closely by Roberts, Bettencourt, and Mark “Snark” Jones. Two seconds back came Harry “Nosmo” Klinz-^ mann, Spencer, Richichi, Bruce Hammer, Rich Schlachter, Steve Gervais and Mike Cone in a clump.

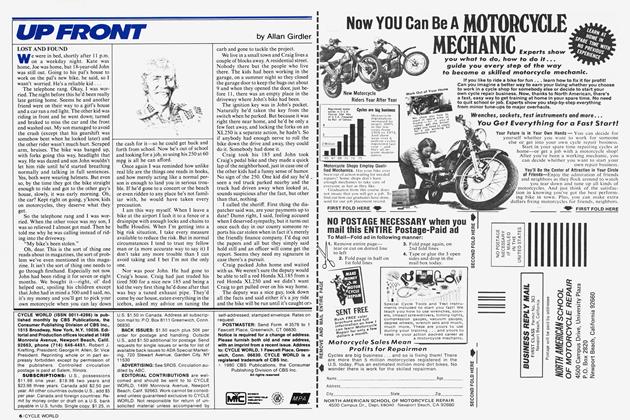

And then it was Roberts and Spencer, going away. Jones crashed hard when his front tire went flat. Cooley and Schlachter battled, Schlachter waving his fist at* Cooley and gesturing to officials, trying unsuccessfully to demand a black flag for Cooley’s four stroke, which was blowing oil everywhere. Bettencourt was close behind, and when Cooley heard some bad, crank-failure-type-noises at the downshifts for the corkscrew turn, he went, straight off the track and parked, nearly taking still-racing Bettencourt with him. Roberts and Spencer traded the lead in what might have looked like a race, but which was revealed for what it was by the stopwatch. Play. Games. Wheelies for the crowd.

The lap times tell the story. 1:1 Os, 1:11s, a few 1:09s for most of the first race. On the 23rd lap Roberts dropped the charade and turned up the wick, cutting a series of1:08s, notching back to 1:09s, building a cushion which would grow to 13 seconds by the finish.

Spectators could witness the troubles Spencer described later—the bouncebounce-slide out of turn 7, an action often almost ending in a high-slide when Spencer tried to come off the turn hard in spite of the bike. But then, Roberts’ aluminum-framed 500 had a twichiness of its own exiting that turn in the closing laps, a wobble that lasted all the way from turn 7 to turn 8 and which didn’t seem to bother Roberts at all.

The view from third, from aboard Richard Schlachter’s Bob MacLeanowned Yamaha TZ750, was a realistic one. “Kenny and Freddie really took off,” Schlachter would tell reporters in the pits. “If I tried to stay up with them I might have crashed.”

Bettencourt, in fourth, had his most exciting moment when a Chihuahua ran across turn 1 just as Bettencourt arrived there. “I almost passed out,” said Bettencourt. “That was the most exciting moment. The neatest thing was watching Kenny for three laps. It was like a dream—here I am right behind Kenny Roberts, and Spencer was behind me for two laps.”

Richichi, a mechanic from Queens, New York City, nailed down fifth after passing Gene Romero for good. Romero, meanwhile, was completely dejected with his sixth place finish. He wouldn’t find out until later that the reason he couldn’t go faster was that his bike’s frame was badly bent from a crash caused by a lappee at Loudon, the damage being so severe that the front and rear wheels wouldn’t line up, the bike wanting to fall into right handers and resist turning left. All Romero was sure of was that he was mad. He called the bike junk, berated its power, handling and brakes, and declared that he and tuner Don Vesco were through as a team.

David Emde was seventh in the first leg, ahead of Miles Baldwin, Harry Klinzmann (whose front brakes acted up, requiring several pumps at every turn due to faulty caliper installation), and Texas privateer Mike Cone.

* * *

“Were you really racing at any time during the first leg?” a reporter asked Roberts between heats.

“No,” Roberts replied, shaking his head.

* * *

Between legs, after changing to fresh tires, Kanemoto drained the oil from the> Yamaha’s monoshock and found it to be more foam than liquid. He refilled the monoshock with oil and Spencer headed for the grid.

Cooley’s Suzuki rolled to the back of the starting grid, complete with a new engine and a new right clip-on, inspection between races revealing the old one to have cracked through its mounts. Hammer would start well behind as well, having pitted with a seized steering damper in the first leg.

* * *

“Do you have any plan for the second leg?” Roberts was asked before he strapped on his helmet.

“I’ll hang back for awhile, then race for awhile. If Freddie is doing 1:08s, I’ll make my bid earlier. But if he’s doing 1:09s and 1:10s I’ll wait until about 10 laps from the finish. This thing is hard to ride during the last five laps because the suspension pumps up and the tires slide, so I’ll probably want to make my move with about 10 laps to go.”

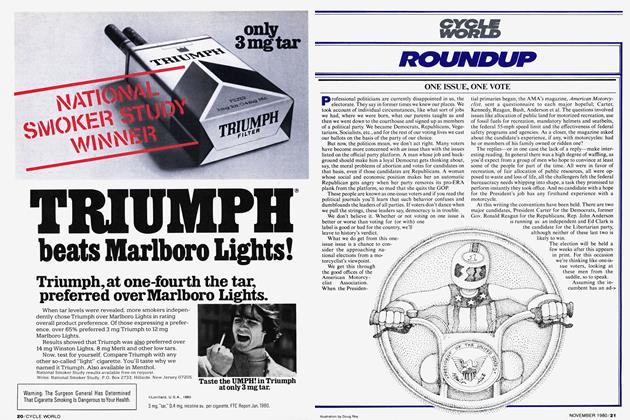

This time, Roberts led the start, and again Roberts and Spencer left third-place Schlachter and fourth-place Bettencourt behind. But this time, when Roberts flexed his skill for all to see, he did it precisely 15 laps from the finish, and brought the times down to an official new lap record of 1:07.28 and banged off a string of four laps in the 1:07s and five in the 1:08s, followed by cruising 1:09s. That was enough for Roberts to lap Schlachter and everyone else except Spencer. The last two laps, Spencer’s Yamaha barely ran, spitting and popping, firing two cylinders with a disabled ignition.

By finishing third overall, Schlachter gained enough points over non-finishing rival Cooley that he retained his AMA F-l championship for another year.

OVERALL RESULTS

Superbike

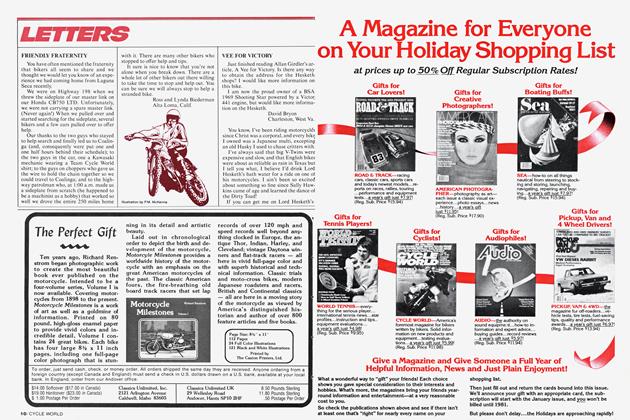

£ Cl plain got beat,” said Superbike ProIduction Champion Wes Cooley. “Spencer was just going faster, same as last year. I got a good start, and then he went by me when we caught a slower rider. He went by me so fast, got around that guy, I hesitated for a second and that was where he put the first 20 feet on me. After that he just went a little quicker and a little faster.”

That was the story of the Superbike Production race. Maybe the Yoshimura mechanics could have changed the rear tire on Cooley’s Vetter Suzuki, instead of starting the race with the same rear tire used in qualifying. Perhaps a fresher tire would have eliminated or improved the sliding rear end problem Cooley was forced to deal with late in the race, but maybe not. But Spencer complained of a sliding rear tire as well.

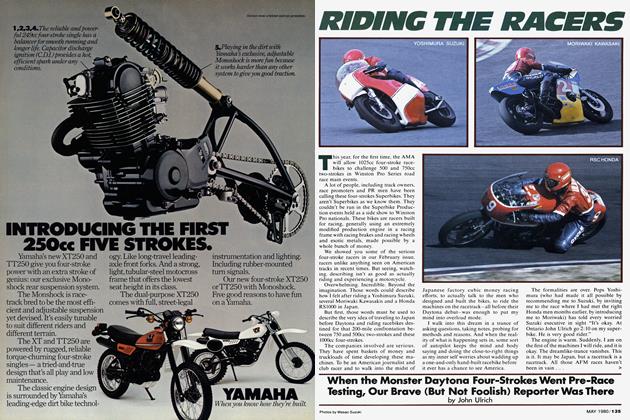

Done right, a four-valves-per-cylinder engine should hold an advantage over twovalves-per-cylinder engines in that more intake valve area is exposed per degree of crankshaft rotation, improving low end and mid range power and resulting in a better launch off the corners. The fourvalve Hondas didn’t exploit that theoretical advantage earlier in the season because they lacked the total valve area of the Yoshimura Suzukis—the Hondas didn’t use big enough intake valves.

But lately the Hondas have been running just fine, especially off the corners. Team Honda’s chief racing mechanic, Udo Geitl, will admit to developing new camshafts that radically improve the powerband of the Honda engine, but says nothing about larger valves.

No matter. The result of more power in the right places, no mechanical failures and Fast Freddie’s brilliant riding was simply that Spencer won. Six laps into the race Spencer passed Cooley for the lead, and slowly pulled away.

David Aldana was third on his Kawasaki Motors Corp. Superbike, a long way back and obviously fighting and wrestling the motorcycle all the time.

“When they (Wes and Freddie) started leaving, I thought to myself that 16 points (in the Superbike Championship) is better than throwing it away,” Aldana confessed later.

“Spencer did a few scaries in turn nine,” said Randy Hall, the Kawasaki engineer in charge of the Superbikes. .

“Yeah,” answered Aldana. “That’s that edge you have to be on to win. Cooley was on it, too. I could ride like I did for third all day, but to win takes riding right on that edge of being out of control and crashing. I wish I could have stayed with them, but I couldn’t. Another thing is that I picked the wrong (rear) tire, that 2190 (Goodyear) instead of a 2460.”

Behind, the privateer and semi-privateer battle raged. Harry Klinzmann had his Racecrafters Kawasaki in what appeared to be a secure fourth until the bike’s clutch basket disintegrated two laps from the finish. That left Roberto Pietri and his Larry Worrell-tuned Honda in fourtfi after fighting off the charges of privateers Carry Andrew (who owns, built and tunes his KZ1000 out of his Van Nuys, California high-performance shop, HyperCycle), Mike Spencer (Champion Motorcycles KZ650) and Chuck Parme (Champion/Kal Gard KZ 1000). In his strongest ride of the year, Pietri turned one lap at 1:11.89, a time that would have been competitive for the 1978 Superbike win.

Parme, hurting from breaking his hand at Atlanta, was faced with his hand going numb, the engine refusing to rev out down the straights and a new, trick thin-wall set of fork tubes flexing terribly.

Parme’s combination of problems was enough for Mike Spencer, self-sponsored service manager at Champion Motorcycles, (a Kawasaki dealer in Costa Mesa, California), to put his 855cc home-built KZ650 into sixth place to stay.

What about Eddie Lawson? Lawson had a strong 12-point lead in Superbike Production Championship points coming into Laguna, and saw it all evaporate when his bike blew second gear during a movie filming session just before timed qualifying. Lawson moodily missed qualifying while Kawasaki mechanics replaced his bike’s engine with one rejected by Aldana the day before in practice. Team Kawasaki’s only assembled spare engine was already in Aldana’s bike. So the mechanics fixed what they thought was wrong with the faulty engine, put it in Lawson’s bike, and learned to their dismay (when they fired up the machine just in time for the start of the race) that it ran on only three cylinders. Lawson rode it that way, working his way from last to ninth, before the engine started making serious mechanical failure-type noises, and Lawson pitted. That turned the Superbike points lead over to Cooley with 88 points, making Lawson second with 85 points and Aldana and Freddie Spencer tied for third with 79 points each.

RESULTS

250 Expert

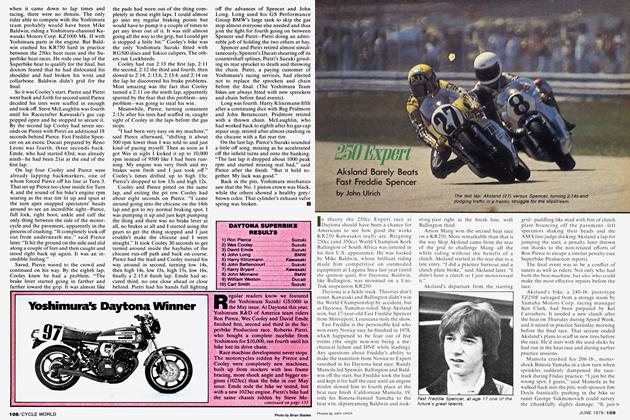

CCI better go and get my back protecItor,” said Eddie Lawson just before the start of the Laguna Seca 250 Expert race, as he walked from the grid into the pits. “If I’m gonna crash, it’s gonna be in this one.”

Lawson was mad. He had gone to Laguna Seca leading the Superbike Production championship, and had seen his points lead vanish, blown away by a transmission broken into shrapnel in his qualifying engine and a wayward camshaft in his race engine. Lawson had only two bikes to ride at Laguna, one Superbike and one 250. The Superbike race was history, and he hadn’t finished.

Winning the 250cc race on his Steve`-Johnson-tuned KR250 (the only non-Ya maha in the race) would at least salvage some of his dignity, plus pay him a $5000 Kawasaki win bonus.

In the pits, Lawson slipped a blue foam back pad between his t-shirt and leathers, then returned to the grid. - Lawson was serious. Lawson won.

Glen Shoper led the start and stayed in front for two laps until Lawson worked his way into the lead. Then, as Lawson pulled away, Shopher held second for three laps, then third as Dave Busby got by. When ,~Shopher crashed on oil left in the cork screw (oil which had already taken out John Glover on the second lap), the finish ing order was partially set-Lawson alone in first, Busby by himself in second despite continuing suspension problems.

The one rider who Lawson most ex pected to give him competition, Gennady Luibimsky, had crashed on cold tires on the first lap, after missing the warm-up lap.

All that remained was for Colorado's Rusty Sharp to get clear of Dan Chiv ington for third, which Sharp did in spite of starting the race on used tires, an eco nomical move good for the privateer wal let but hard on lap times. Sharp's move away from Chivington was visibly accom panied by on-the-edge riding and grim determination.

Lawson, on the other hand, looked al most calm as he dealt with a transmission popping out of gear and reeled off a steady series of 1:12 laps, 10 of them in all, rang ing from 1:12.2 to 1:12.9, his other laps being a mix of 1:13s, 1:14s, and a heavy traffic 1:15.

I hat's more like it," said Lawson at terwards. "I race for the money. If I couldn't get paid to race, I'd just ride my dirt bike, go trail riding in the desert. Give me that bonus money!"

RESULTS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue