Blake Yamaha XS750

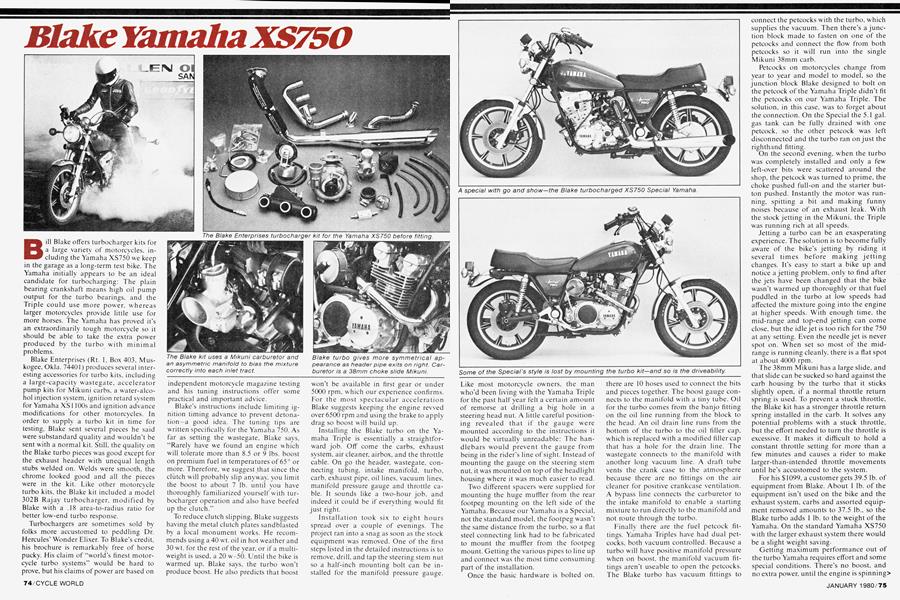

Bill Blake offers turbocharger kits for a large variety of motorcycles, including the Yamaha XS750 we keep in the garage as a long-term test bike. The Yamaha initially appears to be an ideal candidate for turbocharging: The plain bearing crankshaft means high oil pump output for the turbo bearings, and the Triple could use more power, whereas larger motorcycles provide little use for more horses. The Yamaha has proved it’s an extraordinarily tough motorcycle so it should be able to take the extra power produced by the turbo with minimal problems.

Blake Enterprises (Rt. 1, Box 403, Muskogee. Okla. 74401) produces several interesting accessories for turbo kits, including a large-capacity wastegate, accelerator pump kits for Mikuni carbs, a water-alcohol injection system, ignition retard system for Yamaha XS1100s and ignition advance modifications for other motorcycles. In order to supply a turbo kit in time for testing, Blake sent several pieces he said were substandard quality and wouldn't be sent with a normal kit. Still, the quality on the Blake turbo pieces was good except for the exhaust header with unequal length stubs welded on. Welds were smooth, the chrome looked good and all the pieces were in the kit. Like other motorcycle turbo kits, the Blake kit included a model 302B Rajay turbocharger, modified by Blake with a .18 area-to-radius ratio for better low-end turbo response.

Turbochargers are sometimes sold by folks more accustomed to peddling Dr. Hercules’ Wonder Elixer. To Blake’s credit, his brochure is remarkably free of horse pucky. His claim of “world's finest motorcycle turbo systems” would be hard to prove, but his claims of power are based on independent motorcycle magazine testing and his tuning instructions offer some practical and important advice. Blake’s instructions include limiting ignition timing advance to prevent detonation—a good idea. The tuning tips are written specifically for the Yamaha 750. As far as setting the wastegate. Blake says. “Rarely have we found an engine which will tolerate more than 8.5 or 9 lbs. boost on premium fuel in temperatures of 65° or more. Therefore, we suggest that since the clutch will probably slip anyway, you limit the boost to about 7 lb. until you have thoroughly familiarized yourself with turbocharger operation and also have beefed up the clutch.”

To reduce clutch slipping. Blake suggests having the metal clutch plates sandblasted by a local monument works. He recommends using a 40 wt. oil in hot weather and 30 wt. for the rest of the year, or if a multiweight is used, a 20 w~50. Until the bike is warmed up, Blake says, the turbo won’t produce boost. He also predicts that boost won’t be available in first gear or under 5000 rpm. which our experience confirms. For the most spectacular acceleration Blake suggests keeping the engine revved over 6500 rpm and using the brake to apply drag so boost will build up. Installing the Blake turbo on the Yamaha Triple is essentially a straightforward job. Off come the carbs, exhaust system, air cleaner, airbox, and the throttle cable. On go the header, wastegate, connecting tubing, intake manifold, turbo, carb, exhaust pipe, oil lines, vacuum lines, manifold pressure gauge and throttle cable. It sounds like a two-hour job, and indeed it could be if everything would fit just right.

Installation took six to eight hours spread over a couple of evenings. The project ran into a snag as soon as the stock equipment was removed. One of the first steps listed in the detailed instructions is to remove, drill, and tap the steering stem nut so a half-inch mounting bolt can be installed for the manifold pressure gauge.

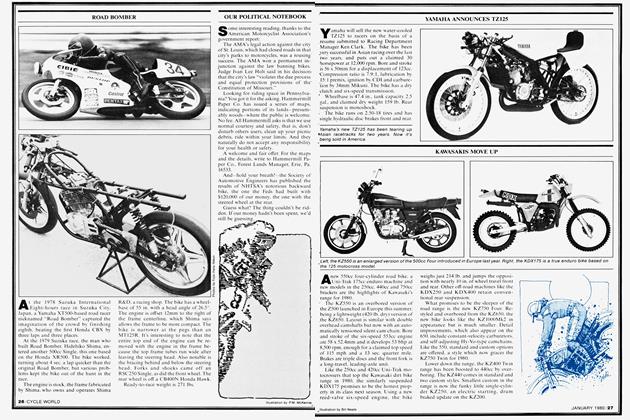

Like most motorcycle owners, the man who’d been living with the Yamaha Triple for the past half year felt a certain amount of remorse at drilling a big hole in a steering head nut. A little careful positioning revealed that if the gauge were mounted according to the instructions it would be virtually unreadable: The handlebars would prevent the gauge from being in the rider’s line of sight. Instead of mounting the gauge on the steering stem nut. it was mounted on top of the headlight housing where it was much easier to read.

Two different spacers were supplied for mounting the huge muffler from the rear footpeg mounting on the left side of the Yamaha. Because our Yamaha is a Special, not the standard model, the footpeg wasn’t the same distance from the turbo, so a flat steel connecting link had to be fabricated to mount the muffler from the footpeg mount. Getting the various pipes to line up and connect was the most time consuming part of the installation.

Once the basic hardware is bolted on.

there are 10 hoses used to connect the bits and pieces together. The boost gauge connects to the manifold with a tiny tube. Oil for the turbo comes from the banjo fitting on the oil line running from the block to the head. An oil drain line runs from the bottom of the turbo to the oil filler cap, w hich is replaced with a modified filler cap that has a hole for the drain line. The w^astegate connects to the manifold with another long vacuum line. A draft tube vents the crank case to the atmosphere because there are no fittings on the air cleaner for positive crankcase ventilation. A bypass line connects the carburetor to the intake manifold to enable a starting mixture to run directly to the manifold and not route through the turbo.

Finally there are the fuel petcock fittings. Yamaha Triples have had dual petcocks, both vacuum controlled. Because a turbo will have positive manifold pressure when on boost, the manifold vacuum fittings aren't useable to open the petcocks. The Blake turbo has vacuum fittings to

connect the petcocks w ith the turbo, which supplies the vacuum. Then there’s a junction block made to fasten on one of the petcocks and connect the flow from both petcocks so it will run into the single Mikuni 38mm carb.

Petcocks on motorcycles change from year to year and model to model, so the junction block Blake designed to bolt on the petcock of the Yamaha Triple didn’t fit the petcocks on our Yamaha Triple. The solution, in this case, was to forget about the connection. On the Special the 5.1 gal. gas tank can be fully drained with one petcock, so the other petcock was left disconnected and the turbo ran on just the righthand fitting.

On the second evening, when the turbo was completely installed and only a few left-over bits were scattered around the shop, the petcock was turned to prime, the choke pushed full-on and the starter button pushed. Instantly the motor was running, spitting a bit and making funny noises because of an exhaust leak. With the stock jetting in the Mikuni, the Triple was running rich at all speeds.

Jetting a turbo can be an exasperating experience. The solution is to become fully aware of the bike’s jetting by riding it several times before making jetting changes. It’s easy to start a bike up and notice a jetting problem, only to find after the jets have been changed that the bike wasn’t warmed up thoroughly or that fuel puddled in the turbo at low speeds had affected the mixture going into the engine at higher speeds. With enough time, the mid-range and top-end jetting can come close, but the idle jet is too rich for the 750 at any setting. Even the needle jet is never spot on. When set so most of the midrange is running cleanly, there is a flat spot at about 4000 rpm.

The 38mm Mikuni has a large slide, and that slide can be sucked so hard against the carb housing by the turbo that it sticks slightly open, if a normal throttle return spring is used. To prevent a stuck throttle, the Blake kit has a stronger throttle return spring installed in the carb. It solves any potential problems with a stuck throttle, but the effort needed to turn the throttle is excessive. It makes it difficult to hold a constant throttle setting for more than a few minutes and causes a rider to make larger-than-intended throttle movements until he's accustomed to the system.

For his $1099, a customer gets 39.5 lb. of equipment from Blake. About 1 lb. of the equipment isn’t used on the bike and the exhaust system, carbs and assorted equipment removed amounts to 37.5 lb., so the Blake turbo adds 1 lb. to the weight of the Yamaha. On the standard Yamaha XS750 w ith the larger exhaust system there would be a slight weight saving.

Getting maximum performance out of the turbo Yamaha requires effort and some special conditions. There’s no boost, and no extra power, until the engine is spinning> at least 6000 rpm and the throttle’s wide open. Just rolling the throttle on at normal cruising speeds or around town doesn’t spin the tire or flatten eyeballs or start the adrenalin flowing. The Yamaha just slowly picks up speed under those conditions. Even when the engine is spinning over 6000 rpm it takes a while for boost to build up, and as soon as it starts building up it’s time to shift to a higher gear and wait for the boost to pick back up again.

It is possible, however, to bang the Triple into first gear, hold the throttle wide open until nine thou, slam the gearshift lever up into second and feel the front tire reach for the sky like the bad guy in a John Wayne Western. And when the throttle is held open, keeping the gases flowing through the engine, the Yamaha lurches through the first three gears almost as fast as the rider can shift. In fourth or fifth there’s enough load on the engine so the bike loses its jack rabbit feeling and slows down the rate of acceleration.

Initial dragstrip performance wasn’t all we had hoped for. On the first day of testing the Yamaha ran 12.63 sec. at 106.13 mph compared to the stock time of 13.44 sec. at 97.82 mph. After running the other turbo bikes and gaining more experience with turbo acceleration and lag, the boost was cranked up by one turn on the wastegate, boosting pressure to just over 10 psi. At that pressure the Yamaha was still running without detonation on premium fuel and the times dropped to 12.30 sec. at 108.82 mph.

In order to get boost in first gear and improve times, the test rider had to rev the motor repeatedly at the lights and take off with the motor at 9000 rpm. Suffice it to say proper acceleration on a turbo requires special technique and practice.

Top speed of the turbo Yamaha at the half mile was 125 mph, slightly more than the 122 mph it’s geared for at red line. Stock top speed was 114 mph at the half mile.

Put in perspective, the turbo Yamaha is more than a second quicker in the quarter and 11 mph faster, which is a substantial improvement. But a stock 1980 Honda CB750 can do the quarter mile in 12.54 sec. at 106.13 mph and any of the fast thousands are quicker in the quarter mile.

Of all the turbocycles evaluated, the Blake was the least fun to ride. Most of the shortcomings of the Blake turbo are in the carb. The throttle cable might just as well have been connected to a shock spring, as the throttle return spring. It was stiff enough to give the dragstrip tester pains in his throttle wrist.

Arnold Schwarznegar could use the Blake’s Mikuni carb spring for leg exercises.

When the carb was opened the Yamaha didn’t accelerate evenly or smoothly at normal speeds. Going into a corner and making a seemingly small adjustment in throttle position would result in a huge change in engine speed, making the Yamaha lift or lower on its shaft drive. It was necessary to warm up the Yamaha before riding and for the first 15 min. in the morning the motor would still die at stop signs. All this was after the jetting was sorted out.

In day-to-day operation the turboequipped Triple was rideable, but not enjoyable transportation. When test riders simply needed to go home or out to lunch or to the bank the Triple sat in the garage while a CX500 or KE250 or XS Eleven was used for transportation. It ain’t easy being tough.

Sound level of the turbo Yamaha, measured by the California Highway Patrol method, was 87 db(A), five decibels louder than the stock Yamaha. The difference in sound was apparent to riders and bystanders, but interestingly enough, the increased sound level seems much higher to riders than listeners.

The car people have convinced lots of innocent folks that turbos provide the power when it’s needed, along with improved economy and reduced emissions; the turbo-equipped Yamaha didn’t convince any test tiders of any of these things. Getting power was difficult because the turbo was too big for the engine. A smaller turbo providing boost at lower engine speeds and less ultimate boost would have been better for normal use. After all, when the wastegate is set to 7 psi, who needs a turbo capable of blowing the head off a motorcycle if only the machine would rev that high? Then there’s the economy. Because the Yamaha didn’t lend itself to highway cruising with the stiff throttle, it didn’t get ridden much out on the highway. Mileage with the turbo installed dropped to an average of 35 mpg, from an average of around 45 mpg the Triple usually turns in. If the carb jetting could have been set closer that could be improved. Finally, there’s the matter of emissions. Without a complete warehouse of equipment, it’s impossible to give a precise evaluation of exhaust emissions. Those people who have tried turbos on cars have found some emissions to be reduced by a properly designed and installed turbo. In any case, installing a turbo on a 1978 or later model motorcycle would be considered tampering by the Govt, and therefore illegal in most places for street use. We didn’t get caught, though.

What must be sacrificed to get those thrills is substantial. First there’s the $1099 cost of the basic package and the day’s labor to install it. Then there’s the increased difficulty of riding the bike with the turbo installed; the stiff throttle return spring, irregular idle, and spotty carbure -tion. It’s even difficult for a rider to keep his left foot on the footpeg because the turbo exhaust pipe wraps around the side of the motorcycle, by the footpeg, interfering with the footpeg.

It all boils down to a matter of application. The Blake turbo, like the other turbo kits available for motorcycles, is essentially a piece of racing hardware. For all practical purposes, if performance on the street is the criterion, the Blake turbo on the Yamaha Triple is not as satisfactory as either a stock Yamaha Triple or a larger displacement motorcycle. But that’s not the point. The point is that a turbo can greatly increase the power of any motorcycle it’s mounted on, as the Blake turbo surely does.

The Blake turbo is a complete package, with generally good equipment supplied. Installation as easy as the ATP turbo and the installation and tuning instructions were good, though including some questionable mounting. The system fit the Yamaha reasonably well, with some sacrifices in ergonomics, as where the muffler wraps around the footpeg.

For all its impracticality, the Blake turbo was for an instant—an instant in which a Kawasaki KZ1000 rider bore a look of total timidity—worthwhile.