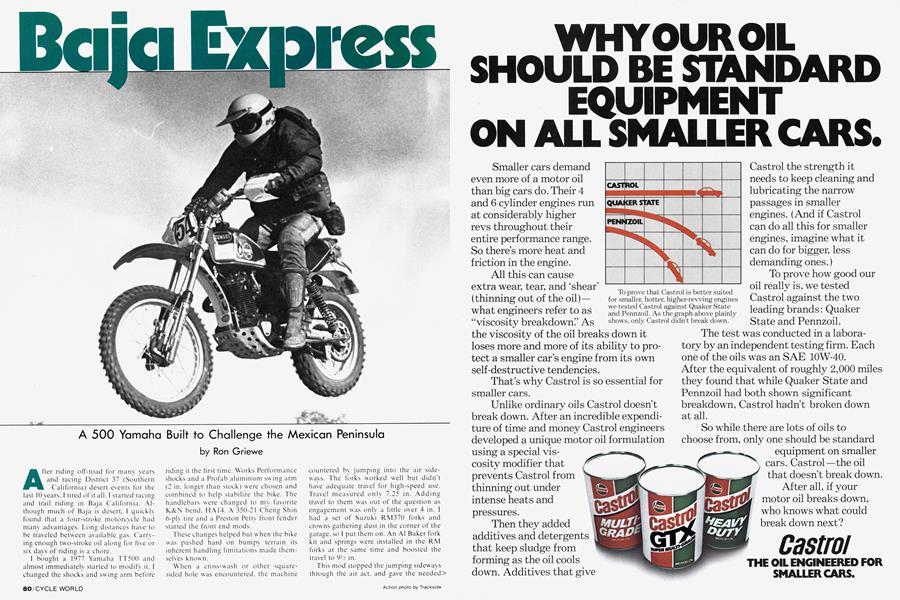

Baja Express

A 500 Yamaha Built to Challenqe the Mexican Peninsula

Ron Griewe

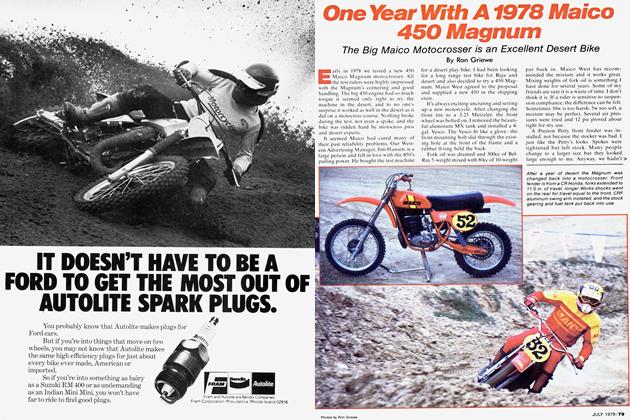

After riding off-road for many years and racing District 37 (Southern California) desert events for the last 10 years. I tired of it all. I started racing and trail riding in Baja California. Although much of Baja is desert. I quickly found that a four-stroke motorcycle had many advantages. Long distances have to be traveled between available gas. Carrying enough two-stroke oil along for five or six days of riding is a chore.

I bought a 1977 Yamaha TT500 and almost immediately started to modify it. I changed the shocks and swing arm before riding it the first time. Works Performance shocks and a Profab aluminum sw ing arm (2 in. longer than stock) were chosen and combined to help stabilize the bike. The handlebars were changed to my favorite K&N bend. HA 14. A 350-21 Cheng Shin 6-plv tire and a Preston Petty front fender started the front end mods.

These changes helped but w hen the bike was pushed hard on bumpy terrain its inherent handling limitations made themselves known.

When a cross-wash or other squaresided hole was encountered, the machine countered by jumping into the air sideways. The forks worked well but didn't have adequate travel for high-speed use. Travel measured only 7.25 in. Adding travel to them was out of the question as engagement was only a little over 4 in. 1 had a set of Suzuki RM370 forks and crow ns gathering dust in the corner of the garage, so I put them on. An AÍ Baker fork kit and springs were installed in the RM forks at the same time and boosted the travel to 9Vi in.

This mod stopped the jumping sideways through the air act. and gave the needed > travel . . . but. On high-speed sliding-type corners, a hesitation in the handling before entering the corner was noticed. This was a little spooky but the cause couldn’t be pinpointed. “Must be frame flex,” I convinced myself.

Naturally the next mod was a custom frame. I chose a chrome-moly one made by Profab. It has almost the same geometry (head angle, engine placement, etc.), but has several advantages over the Stocker. First, by using chrome-moly tubing and a remote oil tank made from aluminum, the frame weight is reduced by almost 9 lb. The remote oil tank rests under the seat and thus helps lower the center of gravity.

Profab owner Pete Wilkins felt the stock frame geometry was good, so he used the same basic layout on his chrome-moly unit. He also equipped the special frame with mounting brackets that would accept all of the TT’s stock components if the buyer desired. Unfortunately the design didn’t prove popular and has since been dropped from production.

A Suzuki PE250 aluminum gas tank was installed on the new frame. It holds 3.2 gal. of gas without being restrictive or ugly. More padding was also added to the front part of the stock seat. A Preston Petty IT rear fender found its way into the package at the same time. The frame gave a much more solid feel to the bike and it no longer felt like it was bending in the middle when a gully was crossed at high speed. But the handling quirk going into high-speed sliders still existed. Hmmm.

About this time my friend Jim Hansen started telling me that fork flex was the problem. “Nonsense,” was my reply. “You have been reading too many magazines.” Finally while in the desert testing another bike, I had the photographer take a picture of the TT in a sweeping high-speed corner. When the prints came back, sure enough, the side force was bending the forks enough that the tire was rubbing against a fork tube.

A set of Betor leading axle forks was acquired from Hatch Accessories. Profab’s beautifully machined aluminum triple clamps mated the forks to the now highly modified bike.

Heavy-duty stainless steel spokes from Hallcraft were installed on D.I.D. rims. All of the spookiness disappeared and a very plush 10 in. of wheel travel resulted. The bike now steered almost as well as a Maico and felt rock steady.

The 38mm Betors had soft springs so air caps were installed. Fourteen psi seemed right. The oil seals started to weep the first ride and replacement was made using Yamaha YZ seals. The Betors work without flaw. They soak up the tiniest of bumps and glide over the biggest without a whimper.

Many small items have also been > changed throughout the project: A Gunnar Gasser throttle pulls the slide on a 38mm Lectron carburetor. Hand guards protect knuckles from cactus and brush. A K&N plug holder and kill button ride on the bars. A home-made brake pedal uses a Husky brake rod. Graham Sheetmetal side number plates to fit a YZ250 have been adapted to the Profab frame. A hollow YZE swing arm bolt and Profab chromemoly axles are used. The heavy exhaust pipe has been replaced with one from Jardine.

I also started to experiment with front tires. The one I settled on is a 3.25 Metzeler. It doesn’t work quite as well as a 3.50 Cheng Shin in deep sand but excels every place else.

Engine development has been almost constant. To get the engine to produce competitive power and still live through a 600or 700mile Baja event has been a real problem. Getting enough power proved much easier than making it stay together. After much frustration and costly breakdowns, the combination that has worked for me is:

— IO1/? to 1 Venolia forged piston.

—Web #88 cam

—S&W valve springs and retainers —38mm Lectron carb with velocity stack —K&N air filter —Ported head —NGK BP8E plug —External Mallory condensor #25010 —Jardine megaphone pipe

Once the engine produced enough power, rapid rear tire and chain wear became a serious problem. Some of them were completely wasted in less than 200 miles. After much experimenting" one tire stood out from the rest: A Barum 460-18 Six-Days tire. Seven to eight hundred miles of Baja at racing speeds was possible without chunking problems. After 800 racing miles the Barum was still usable for another 300-400 miles of normal trailing, fhe Barum is also reasonably priced (usually under $40 retail).

The chain problem was solved using D.I.D.’s super good TR chain. Even under extremely bad conditions, the TR has held up exceptionally well.

The stock steel rear sprocket is durable but I had trouble shearing the stock sprocket studs. Hardened replacement (from Profab) bolts that go through the hub and locking nuts cured that problem.

For a while it seemed as if a front sprocket was worn out every time I checked it. A Malcolm Smith 17T front sprocket cured this annoyance. I even had one of them go more miles than the steel rear one!

After one and one-half years of development and piles of dollars, a good Baja road burner has finally taken shape. Was it worth all the money and work? Sometimes I wonder. But, as with any custom-built scoot, I have the pleasure of knowing I won't see another one exactly like it. And when I jump on it and take off through Baja for a few days, I know it is going to handle well and be reasonably reliable. It is still heavy (270 lb. with ½ tank gas), but the weight isn't noticed so much on Baja's dirt roads. And, when I pull in to get gas, I don't have to mix oil with it. In case you are interested in building a custom TT, here are some costs. (Best you sit down first!)

continued on page 86