TOOLS OF THE TRADE

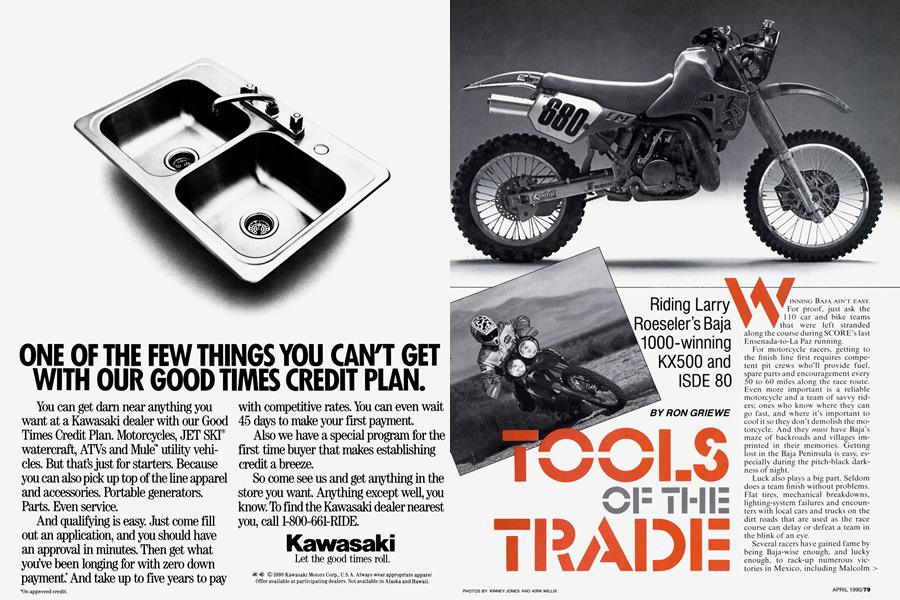

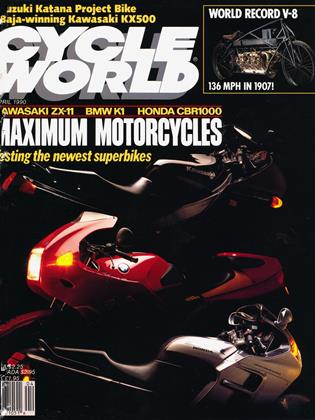

Riding Larry Roeseler's Baja 1000-winning KX500 and ISDE80

RON GRIEWE

WINNING BAJA AIN'T EASY. For proof, just ask the 110 car and bike teams that were left stranded

along the course during SCORE’S last Ensenada-to-La Paz running.

For motorcycle racers, getting to the finish line first requires competent pit crews who’ll provide fuel, spare parts and encouragement every 50 to 60 miles along the race route. Even more important is a reliable motorcycle and a team of savvy riders; ones who know where they can go fast, and where it’s important to cool it so they don’t demolish the motorcycle. And they must have Baja’s maze of backroads and villages imprinted in their memories. Getting lost in the Baja Peninsula is easy, especially during the pitch-black darkness of night.

Luck also plays a big part. Seldom does a team finish without problems. Flat tires, mechanical breakdowns, lighting-system failures and encounters with local cars and trucks on the dirt roads that are used as the race course can delay or defeat a team in the blink of an eye.

Several racers have gained fame by being Baja-wise enough, and lucky enough, to rack-up numerous victories in Mexico, including Malcolm > Smith, J.N. Roberts, Mike Patrick, AÍ Baker, Scott Harden, Dan Ashcraft and Dan Smith. But no one comes close to matching Larry Roeseler’s record number of Baja 500 and 1000 wins. Roeseler, 32, has conquered each race an amazing six times.

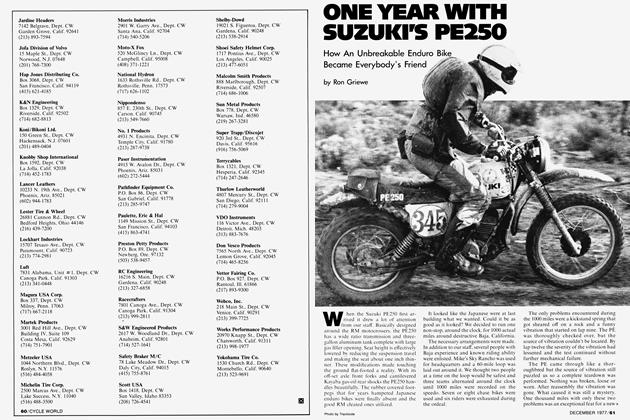

Roeseler’s most-recent win came at the 1989 Baja 1000 in November, where he teamed with Ted Hunnicut Jr. and Danny LaPorte on the Team Green Kawasaki KX500 you see here. The victory didn’t come without drama. Riding the last one-third of the race, Roeseler had increased his team’s lead to a comfortable 30 minutes. Then, 30 miles from the finish, and flat-out in fifth gear (the big Kawasaki is geared for 116 miles per hour on pavement), the bike's drive chain broke, knocking the countershaft sprocket and its retaining clip off the transmission shaft.

Roeseler wasn't carrying a chainbreaker because the team’s Tsubaki chains had proven so reliable in past races, but he did have a spare master link, and, using a rock for a hammer, he managed to get the chain back together. Keeping the countershaft sprocket in place, minus its retaining clip, was solved by riding with his boot heel placed against the sprocket, allowing Roeseler to limp into the next pit area. A mad dash from that pit to the finish gave the team the overall win by a scant six minutes.

Roeseler’s in-the-field ingenuity has been perfected during 27 years of off-road riding. His ability to keep a bike running has helped him become one of America’s best riders at the yearly International Six Day Enduro, where he's won nine gold medals, two silver medals and one bronze.

With Roeseler’s experience and input, Kawasaki has been able to put together a formidable off-road team, much like Husqvarna’s once-dominant crew, of which Roeseler was also a member. Roeseler’s 1000-winning KX benefits greatly from his considerable off-road acumen, and riding it gave us some insight into the amount of modifications necessary to build a competitive Baja bike.

Team Green started with a standard KX500 motocrosser, using the stock frame, swingarm, wheels and brakes. The engine was sent to ProCircuit, a Southern California offroad shop, where the head was modified, the cylinder porting was altered and the company’s exhaust pipe was installed.

Pro-Circuit’s modifications increased the power of the KX engine so it could pull the extremely tall final gearing needed for 100-mph-plus charges across dry-lake beds. Pro-Circuit also altered the valving of the stock KYB fork and shock so the bike could better deal with Baja’s highspeed obstacles.

Sitting on Roeseler’s KX500 two months after the Baja race, you’d have bet that the suspension was too soft, but riding the KX500 soon dispels that opinion. The suspension is remarkable, isolating the rider from any jarring when he’s blasting into cross-ditches at speed. The overall ride is extremely comfortable and controlled, and, yes, the KX is very stable at high speeds.

The powerful, responsive KX500 engine isn’t at all fussy, starting easily (well, for a 500), and delivering a smooth flow of power that builds steadily from just above idle and gets progressively stronger as it stretches into a top end that goes on until tomorrow. There’s never any burst of power, just a steady stream that urges the bike forward.

The bike’s easy-to-use power delivery, tall gearing and smooth suspen-

sion gave Roeseler and company a leg-up on the competition. And, according to Rpeseler, the bike was content to run at maximum engine revolutions for as long as the rider dared. “It runs so well when it’s wound out in fifth that I start feeling guilty,” says Roeseler. “Three hundred miles of this year’s 1000 course were on paved roads. Teddy Hunnicut had one 30-mile section of pavement that was nearly straight. He kept the bike pegged the whole distance without an engine problem. In fact, the engine went the whole race without any problems. And, as you can tell after riding it, the engine’s original piston and ring are still in good shape; the compression is still good.” And, indeed, the KX500 did run incredibly well, despite its 17hour, 1000-mile ordeal.

Actually, everything on the KX500 still performed well, and that’s a compliment to the riders’ performances as well as the handiwork of Pro-Circuit and Team Green’s racing department, which built many special parts for the Baja KX.

For example, the accessory fuel tank, a 3.5-gallon unit from IMS, was modified by cutting out its screw-on filler opening and grafting on a roadracing-type, spring-loaded, quickfiller. Rapid pit stops might not seem like a necessity in a long-distance event like the 1000, but with up to 20 pit stops required in the race, the compounding effects of sluggish stops can be devastating.

Providing enough electricity to power a couple of large, halogen headlights was more involved. Team Green left the stock ignition alone, adding an external lighting system to the end of the stock KX ignition rotor. An ignition rotor from a KZ900 streetbike was bolted to the end of the stock rotor, and then a KZ ignition cover, complete with its eight lighting coils, was attached to a machined adapter plate bolted to the 500’s ignition cover mounts. The extra depth of the 900 cover interfered with the stock shift lever, so the lever had to be shortened slightly. During daylight hours, the stock KX500 ignition cover was used, with the modified lighting-coil system being bolted in place just before dark, a job that consumed only a few minutes.

Team Green also fabricated a lightweight, quickly attached lightbar for the KX500. The complete unit can be installed without tools, again, shaving time lost in the pits. A single gang-plug connects the halogen lights to the power source.

Keeping lights bright at low engine revs is always a problem on dirtbikes.

A battery added to the system will cure the problem, but batteries don’t like the jolts of off-road racing, and there's always the problem of spilled battery acid. Team Green experimented with a new-style, solid-state battery mounted on the lightbar, but vibration soon ruined it. The solution came when the small battery was moved to the pocket of the rider’s enduro jacket, connected to the bike’s lighting system via a short wiring harness and a quick-plug.

How effective were the lights? “They work great,” Roeseler says. “They stay bright regardless of the engine’s speed. There were sections of the course where I couldn’t have gone any faster in the daylight. We use two different lights, one is a spot that puts the light way out there, the other spreads the light so that visibility is good close up.”

Another special item on the KX is a tiny aluminum canister used to hold the tickets issued at each of the race’s checkpoints as proof of the vehicle having completing that section of the course. Most race cars and motorcycles use an empty beer can ducttaped to the vehicle to hold the pieces of paper. But a beer can is often a problem when strapped to the handlebar of a motorcycle, where it interferes with control cables. Hence Team Green’s small, finely crafted canister.

This attention to small details is one of Larry Roeseler’s, and Team Green’s, secrets to winning long, difficult races like the 1989 Baja 1000, where Kawasaki riders also won the 125cc and 250cc classes. And you can place your bets on Team Green being every bit as competitive next year, even as its lead rider approaches an age when most racers have stopped being competitive.

‘T still love to race, and I ride every day that I can,” Roeseler beams. “Maybe I can get lucky and add another couple of Baja 1000 wins to my record. That would be great.” Ê3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

April 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

April 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

April 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupMichelin Pulls Out of U.S. Bike-Tire Market

April 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

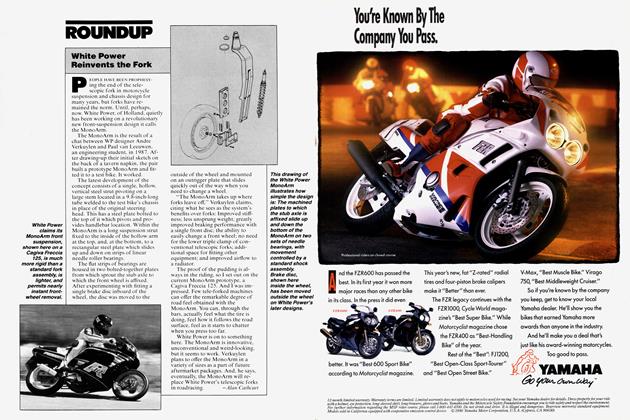

RoundupWhite Power Reinvents the Fork

April 1990 By Alan Cathcart