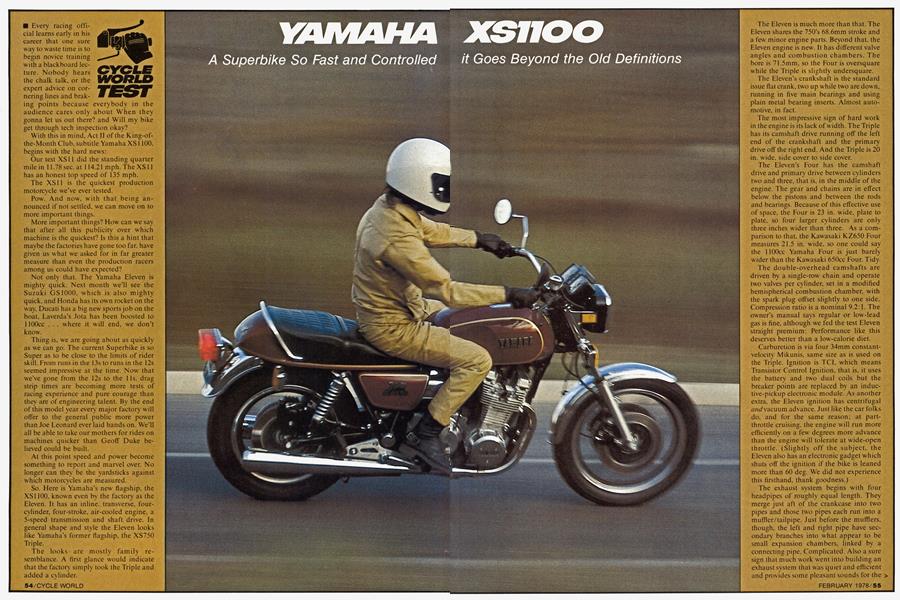

YAMAHA XS1100

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Superbike So Fast and Controlled it Goes Beyond the Old Definitions

Every racing official learns early in his career that one sure way to waste time is to begin novice training with a blackboard lecture. No body hears the chalk talk, or the expert advice on cornering lines and braking points because everybody in the audience cares only about When they gonna let us out there? and Will my bike get through tech inspection okay?

With this in mind. Act II of the King-ofthe-Month Club, subtitle Yamaha XS1100, begins with the hard news:

Our test XS11 did the standing quarter mile in 11.78 sec. at 114.21 mph. The XS1 has an honest top speed of 135 mph.

The XS11 is the quickest production motorcycle we’ve ever tested.

Pow. And now, with that being an nounced if not settled, we can move on to more important things.

More important things? How can we say that after all this publicity over which machine is the quickest? Is this a hint that maybe the factories have gone too far, have given us what we asked for in far greater measure than even the production racers among us could have expected?

Not only that. The Yamaha Eleven mighty quick. Next month we’ll see th Suzuki GS1000, which is also mighty quick, and Honda has its own rocket on the way, Ducati has a big new sports job on the boat, Laverda’s Jota has been boosted to 1 lOOcc . . . where it will end, we don know.

Thing is, we are going about as quickly as we can go. The current Superbike is so Super as to be close to the limits of rider skill. From runs in the 13s to runs in the 12s seemed impressive at the time. Now that we’ve gone from the 12s to the 11s, drag strip times are becoming more tests of racing experience and pure courage than they are of engineering talent. By the end of this model year every major factory will offer to the general public more power than Joe Leonard ever laid hands on. We’ll all be able to take our mothers for rides machines quicker than Geoff Duke believed could be built.

At this point speed and power something to report and marvel over. No longer can they be the yardsticks against which motorcycles are measured.

So. Here is Yamaha’s new flagship, the XS1100. known even by the factory as the Eleven. It has an inline, transverse, fourcylinder, four-stroke, air-cooled engine, a 5-speed transmission and shaft drive. In general shape and style the Eleven looks like Yamaha’s former flagship, the XS750 Triple.

The looks -are mostly family resemblance. A first glance would indicate that the factory simply took the Triple and added a cylinder.

The Eleven is much more than that. The Eleven shares the 750’s 68.6mm stroke and a few minor engine parts. Beyond that, the Eleven engine is new. It has different valve angles and combustion chambers. The bore is 71.5mm, so the Four is oversquare while the Triple is slightly undersquare.

The Eleven’s crankshaft is the standard issue flat crank, two up while two are down, running in five main bearings and using plain metal bearing inserts. Almost automotive, in fact.

The most impressive sign of hard work in the engine is its lack of width. The Triple has its camshaft drive running off the left end of the crankshaft and the primary drive off the right end. And the Triple is 20 in. wide, side cover to side cover.

The Eleven’s Four has the camshaft drive and primary drive between cylinders two and three, that is, in the middle of the engine. The gear and chains are in effect below the pistons and between the rods and bearings. Because of this effective use of space, the Four is 23 in. wide, plate to plate, so four larger cylinders are only three inches wider than three. As a comparison to that, the Kawasaki KZ650 Four measures 21.5 in. wide, so one could say the llOOcc Yamaha Four is just barely wider than the Kawasaki 650cc Four. Tidy.

The double-overhead camshafts are driven by a single-row chain and operate two valves per cylinder, set in a modified hemispherical combustion chamber, with the spark plug offset slightly to one side. Compression ratio is a nominal 9.2:1. The owner’s manual says regular or low-lead gas is fine, although we fed the test Eleven straight premium: Performance like this deserves better than a low-calorie diet.

Carburetion is via four 34mm constantvelocity Mikunis, same size as is used on the Triple. Ignition is TCI, which means Transistor Control Ignition, that is, it uses the battery and two dual coils but the breaker points are replaced by an inductive-pickup electronic module. As another extra, the Eleven ignition has centrifugal ¿/«¿/vacuum advance. Just like the car folks do. and for the same reason; at partthrottle cruising, the engine will run more efficiently on a few degrees more advance than the engine will tolerate at wide-open throttle. (Slightly off the subject, the Eleven also has an electronic gadget which shuts off the ignition if the bike is leaned more than 60 deg. We did not experience this firsthand, thank goodness.)

The exhaust system begins with four headpipes of roughly equal length. They merge just aft of the crankcase into two pipes and those two pipes each run into a muffler/tailpipe. Just before the mufflers, though, the left and right pipe have secondary branches into what appear to be small expansion chambers, linked by a connecting pipe. Complicated. Also a sure sign that much work went into building an exhaust system that was quiet and efficient and provides some pleasant sounds for the rider. Which the system does.

Also impressive is the engine mounting system, in rubber biscuits sandwiched between the engine mount brackets and the frame mounts. These biscuits are tuned and compressed by struts, one for the front mounts and one for the rear. (When we saw the pilot Elevens at the Yamaha plant, we also saw their test equipment. They have a computer which measures the vibrations of both the engine and the frame, egad, and then they build the mounts and insulation so the vibrations cancel each other.

Primary drive is Ely-Vo chain, with a cush drive on the shaft which takes the drive from the chain to the clutch, on the right behind the crankcase. Then comes the gearbox proper and then the drive turns a right angle, with a ring gear driving a pinion at the front of the driveshaft.

The driveshaft itself is new and has an automotive-type U-joint at the front and a splined slip joint at the rear. The XS750 has a constant-velocity U-joint at the pivot.

The CV joint is a better system, in theory, but Yamaha’s tech people say the CV joint must be larger for a given stress than a plainer car-type unit. The Eleven has more power and the U-joint must fit a limited space, hence the simpler system.

Because Yamaha has made the Eleven engine narrow for its displacement, the engine is also long, approximately one inch longer than the Triple, crankshaft center to swing arm pivot.

The Eleven’s wheelbase is fully three inches longer than the 750’s and at is a long w heelbase for any bike.

Attention has been paid to stiffness, frame is double cradle and is quite wide at the swing arm pivot, which takes the force from the driving wheel, and at the steering head, where there braces and overlap

ping plates, all to avoid the dreaded wobble which made earlier Superbikes so infamous.

Suspension needs mention only for the record, being telescopic forks and shocks/ springs on a normal sort of shaft-drive ssving arm, albeit the various parts are good and big. The rear springs have the usual provision for pre-load. So do the fork springs, with a rubber cap covering a pushand-twist cam which is adjusted with a screwdriver. Good touch and one seen on other large Yamahas this year.

There’s one disc brake in back and two in front, again like the XS750 except larger. Wheels are cast aluminum and the Eleven has self-canceling turn signals, a fuel gauge, the usual set of warning lights. The long wheelbase allows the generous fuel tank to be fairly narrow because it can also be long.

If there is a penalty for this otherwise carefully done chassis/engine/drivetrain, it must be weight; with half a tank of fuel the Eleven tips the scales at 601 lb.

In operation, the engine is nearly faultless. The carbs are fitted with a two-stage choke and warm-up lever. You pull all the way out and the engine fires in a few turns, no matter how cold. After a couple seconds the lever can be pushed in one notch.to keep JHe the engine at a fast idle while you

don helmet, gloves, etc. Then push the lever all the wav in and ride away.

For the first few' hundred miles, there is the impression that there is no powerband as such. Turning the throttle simply brings on a great burst of smooth, silent power, as much as any mortal can use, instantly. Not until the rider is used to this will the throttle be more than cracked. When that happens, the Eleven jumps forward at unbelievable speed, until the needle runs past 6 thou.

Then the power gets stronger.

The figures are incredible. They do not speak for themselves, though, because the plain figures don’t do justice to the acceleration on tap.

The Eleven delivers a physical rush and an emotional rush, all in one great silent leap. The tach needle spears into the red, the next gear snicks into place and the bike jumps forward again. The brute power at the low end spins the back tire, jacks the rear of the bike and tries to walk the beast sideways unless the rider has the machine dead straight. And it keeps right on building, through the traps in fourth and on up to that top speed.

About that. The usual test is a half-mile run at the certified radar gun. The Eleven did that at 126 mph, with more on tap. This bike is faster than the normal test. We have no place where we can legally run a machine of this potential flat out w hile one of the crew-the man who drew the short straw, as you’d guessstands on the white line and reads the numbers as the rocket past just inches away.

continued on page 60

What we have done is observed 135 mph on the tach. We’ve seen Elevens top that, with a slight downhill run, at Yamaha’s test track. We are thus willing to say the Eleven’s top speed is 135.

The old rule still holds. There is no substitute for cubic centimeters. Because the Eleven has all this power at all engine speeds, there seldom is a need to downshift or even to plan a passing drill more than a second in advance. Just turn the tap and around you go, or up you go, or anything.

And it’s quiet. . . but not that quiet. At full power the exhaust issues a pleasant little snarl, which sounds like a contradiction until you hear it.

Smooth? My word yes. All the engineering talk of rubber mounts and sympathetic tuning sounds like just talk. And then the skeptic realizes that the mirrors are clear as a camera’s viewfinder. The grips have not so much as a tingle. Another outfit had the word first, but still, the Eleven glides along.

Enough of this rapture. If there is a section of drivetrain not quite up to the engine’s standards, it’s the gearbox. Not the ratios, although seems as if this much power would allow a wider spread between fourth and fifth, that is, an almost-overdrive for easy cruising on the flat.

But that could be an option. Better they work first on the gearshift.

BMW has a clunk, and the Yamaha Eleven has a clank. Especially in the lower .gears, whether the clutch is used completely or fanned, no matter if the lever is leaped on or prodded with all deliberate speed, it clanks. Seems to be there as a result of something else. Inspection of a dismantled gearbox (No, we didn't break it. Fart of the factory’s training equipment) shows a progression in the size and spacing of the dogs which engage the various little wheels. The dogs for first are widely spaced, the dogs for fifth are closely spaced and so forth. This allows the gear wheels to engage with each other smoothly and provides some clearance and takes up some of the shock, which can’t be avoided in an engine this big and strong. No big thing, anyway, and one which doubtless will be reduced as the factory gets more practice.

Braking performance is impressive more for the work done well than for actual stopping distances, which were about average. The Eleven weighs a bunch and the three discs stop the Eleven with no drama. At full braking the rear wheel is almost completely unloaded and at that extreme it did skip the rear tire off the ground a couple times. We experienced nothing like this on the road, indeed, the riders who weren’t at the track were surprised to hear it happened. They found the brakes powerful and trouble-free.

The word for the Eleven’s handling is stable. Remember those three inches added to the wheelbase. Eleven vs XS750? One inch is between front axle and crankshaft centerline, the second is from crankshaft to swing arm pivot and the third is from pivot to rear axle. Evenly distributed, then. The Eleven is long and likes to go straight. It’s nicely balanced fore and aft. so it doesn’t want to go straight against the rider’s will and we’d guess, not having the equipment which proves this, that the bike has a fairly high polar moment of inertia, meaning the mass is spread out within the wheelbase. Engineers say this makes the mass less likely to change direction, a good attribute for a sporting bike this size. (A low polar moment, allowing darts and instant flicking from side to side, is the better way for a smaller sports machine.)

In sum, what you have is a motorcycle that’s happy at speed; while the speed itself may be enough to cause second thoughts, the rider never has the slightest hint that the bike itself is about to do anything except go where pointed.

Cornering clearance is fine. A peg may touch down if desired but there’s not much point in such bravado. The Eleven is too damned big to be pitched about. What the Eleven likes most is smoothness; firm pressure on the bars to lean it into the turn and no sudden moves once committed to the turn. Naturally one must be careful with the power unleashed coming out. And if the rider tries to do two things at once, for instance braking and turning or getting quickly on the power while still getting into cornering attitude, the Eleven will shake its head, slowly but with the meaning plain: Enough.

It’s coming from the suspension, which is tuned for road riding, rather than from a flexible frame or some such horror. Hard to complain overmuch about this because it doesn’t happen except at maximum, where the public road rider has no business being nyway.

And yet. a little suspension tuning uldn’t hurt. The ride of course has been sted and calibrated for the sporting man. with perhaps an extra dash of g comfort thrown in. For the that's w'hat the Eleven delivers, hile there is this shortcoming at eed. there’s also a gap or two in the ns. The rear wheel will bottom p dip, and on older sections of the erstate the front and back set up someg of a hobby-horse effect. Only on e roads, mind, and older ones at that, distances between breaker strips etting the suspension engineers tten about when they made their tions.

onomics begin with the bars, shaped Id wheelbarrow-style dictated by w heelbase and the length of the tank.

>n. Even though the tank is >ng. it’s also long enough to stretch one of the shorter chaps here: legs too far apart for long rides, he said. Grips are too small and too hard. Nip over to the Kawasaki store and (with coat collar up) latch onto the grips from the Zl-R. (This also applies to Honda, Suzuki. Ducati et al.) The seat seemed a bit too soft and too square after a couple hours in the saddle. The canceling signals are universally approved and need no more review. There don’t appear to be any service problems, what with the electronic ignition and Yamaha’s cleverly hinged rear fender and little keeper cables to secure the swing arm when the rear wheel must come off.

The shaft drive is mostly noticeable here because of the chain’s absence. No jangle, no spray cans. The length of the machine and the swing arm serve to minimize the rise and fall of the chassis, so apparent in the smaller, shorter and lighter BMW models.

The Eleven’s seat is semi-permanent, being held by four bolts. There are separate helmet locks and stowage compartments for tools, etc., and the little space behind the seat is used for the mysterious black box, which no owner in sound mind would mess with.

The penalty for that whopping great engine and dazzling speed is of course paid at the gas station. The Eleven got 40 mpg on normal test, dropping into the 30s when used with, uh, vigor. Even so, there are smaller engines in slower bikes that don’t do much better, or as well, maybe.

Philosophy is the key with a model like that. Does anybody need this much engine, this much speed? No. Are we entitled to have our choice when we pay our money? Damn straight we are. A lot of enthusiasts are making that choice, so now Yamaha has something for them.

The something goes beyond the numbers.

One of our crew rode the Eleven to Husqvarna’s 1978 show. After the show, several of the pro Husky riders and tuners spotted the Eleven. (They like motorcycles of all kinds, just as we do.)

“Is it as scary as they say?”

“Scary? Not at all. Quick is what it is. Here, give it a try.”

Now. These are ISDT enduro riders, fearless competitors who roar up hills that would sprain Superman’s ankle.

They all wanted to try the Eleven and each man came back with his eyes big as hard-boiled eggs. Oh, the speed, the power, the rush.

They also came back with new respect for our road man. Gosh, to ride something that fast, in public, out there on that hard black stuff with the trucks and the semiconscious.

“Listen, on your way home, you be careful, hear?”

Not to worry. The Yamaha XSÎ1 is a benchmark motorcycle, not because of the speed but because it’s so civilized. The Eleven offers power that doesn't tend to corrupt.

YAMAHA

XS1100

$2989

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsThe Troubleshooters

February 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

February 1978 By A.G. -

Roundup

RoundupShort Strokes

February 1978 By Tim Barela -

Features

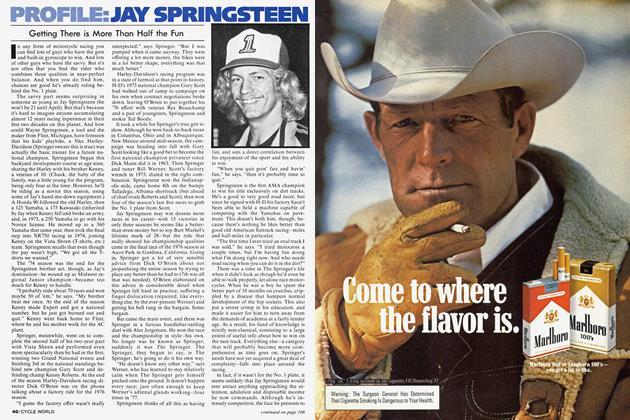

FeaturesProfile: Jay Springsteen

February 1978 -

Competition

CompetitionThoughts From the Back of the Wrecker

February 1978 By Peter Vamvas