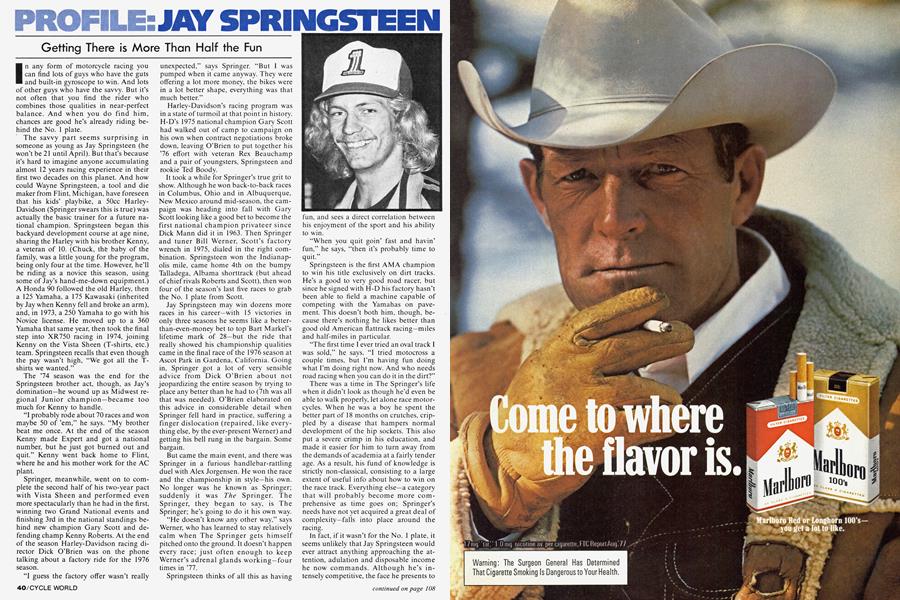

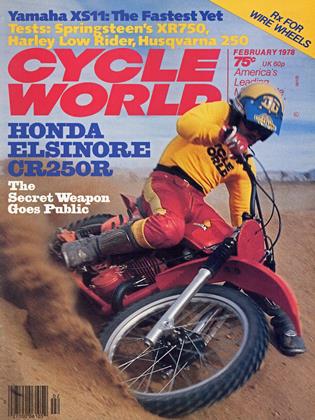

PROFILE: JAY SPRINGSTEEN

Getting There is More Than Half the Fun

In any form of motorcycle racing you can find lots of guys who have the guts and built-in gyroscope to win. And lots of other guys who have the savvy. But it’s not often that you find the rider who combines those qualities in near-perfect balance. And when you do find him, chances are good he's already riding behind the No. 1 plate.

The savvy part seems surprising in someone as young as Jay Springsteen (he won’t be 21 until April). But that’s because it’s hard to imagine anyone accumulating almost 12 years racing experience in their first two decades on this planet. And how could Wayne Springsteen, a tool and die maker from Flint, Michigan, have foreseen that his kids’ playbike, a 50cc HarleyDavidson (Springer swears this is true) was actually the basic trainer for a future national champion. Springsteen began this backyard development course at age nine, sharing the Harley with his brother Kenny, a veteran of 10. (Chuck, the baby of the family, was a little young for the program, being only four at the time. However, he’ll be riding as a novice this season, using some of Jay’s hand-me-down equipment.) A Honda 90 followed the old Harley, then a 125 Yamaha, a 175 Kawasaki (inherited by Jay when Kenny fell and broke an arm), and, in 1973, a 250 Yamaha to go with his Novice license. He moved up to a 360 Yamaha that same year, then took the final step into XR750 racing in 1974, joining Kenny on the Vista Sheen (T-shirts, etc.) team. Springsteen recalls that even though the pay wasn’t high, “We got all the Tshirts we wanted.”

The ’74 season was the end for the Springsteen brother act, though, as Jay’s domination—he wound up as Midwest regional Junior champion—became too much for Kenny to handle.

‘T probably rode about 70 races and won maybe 50 of ’em,” he says. “My brother beat me once. At the end of the season Kenny made Expert and got a national number, but he just got burned out and quit.” Kenny went back home to Flint, where he and his mother work for the AC plant.

Springer, meanwhile, went on to complete the second half of his two-year pact with Vista Sheen and performed even more spectacularly than he had in the first, winning two Grand National events and finishing 3rd in the national standings behind new champion Gary Scott and defending champ Kenny Roberts. At the end of the season Harley-Davidson racing director Dick O’Brien was on the phone talking about a factory ride for the 1976 season.

“I guess the factory offer wasn’t really unexpected,” says Springer. “But I was pumped when it came anyway. They were offering a lot more money, the bikes were in a lot better shape, everything was that much better.”

Harley-Davidson’s racing program was in a state of turmoil at that point in history. H-D’s 1975 national champion Gary Scott had walked out of camp to campaign on his own when contract negotiations broke down, leaving O’Brien to put together his ’76 effort with veteran Rex Beauchamp and a pair of youngsters, Springsteen and rookie Ted Boody.

It took a while for Springer’s true grit to show. Although he won back-to-back races in Columbus, Ohio and in Albuquerque, New Mexico around mid-season, the campaign was heading into fall with Gary Scott looking like a good bet to become the first national champion privateer since Dick Mann did it in 1963. Then Springer and tuner Bill Werner, Scott’s factory wrench in 1975, dialed in the right combination. Springsteen won the Indianapolis mile, came home 4th on the bumpy Talladega, Albama shorttrack (but ahead of chief rivals Roberts and Scott), then won four of the season’s last five races to grab the No. 1 plate from Scott.

Jay Springsteen may win dozens more races in his career—with 15 victories in only three seasons he seems like a betterthan-even-money bet to top Bart Markel’s lifetime mark of 28—but the ride that really showed his championship qualities came in the final race of the 1976 season at Ascot Park in Gardena, California. Going in, Springer got a lot of very sensible advice from Dick O’Brien about not jeopardizing the entire season by trying to place any better than he had to (7th was all that was needed). O’Brien elaborated on this advice in considerable detail when Springer fell hard in practice, suffering a finger dislocation (repaired, like everything else, by the ever-present Werner) and getting his bell rung in the bargain. Some bargain.

But came the main event, and there was Springer in a furious handlebar-rattling duel with Alex Jorgensen. He won the race and the championship in style—his own. No longer was he known as Springer; suddenly it was The Springer. The Springer, they began to say, is The Springer; he’s going to do it his own way.

“He doesn’t know any other way,” says Werner, who has learned to stay relatively calm when The Springer gets himself pitched onto the ground. It doesn’t happen every race; just often enough to keep Werner’s adrenal glands working—four times in ’77.

Springsteen thinks of all this as having fun, and sees a direct correlation between his enjoyment of the sport and his ability to win.

“When you quit goin’ fast and havin’ fun,” he says, “then it’s probably time to quit.”

Springsteen is the first AMA champion to win his title exclusively on dirt tracks. He’s a good to very good road racer, but since he signed with H-D his factory hasn’t been able to field a machine capable of competing with the Yamahas on pavement. This doesn’t both him, though, because there’s nothing he likes better than good old American flattrack racing—miles and half-miles in particular.

“The first time I ever tried an oval track I was sold,” he says. “I tried motocross a couple times, but I’m having fun doing what I’m doing right now. And who needs road racing when you can do it in the dirt?”

There was a time in The Springer’s life when it didn’t look as though he’d even be able to walk properly, let alone race motorcycles. When he was a boy he spent the better part of 18 months on crutches, crippled by a disease that hampers normal development of the hip sockets. This also put a severe crimp in his education, and made it easier for him to turn away from the demands of academia at a fairly tender age. As a result, his fund of knowledge is strictly non-classical, consisting to a large extent of useful info about how to win on the race track. Everything else—a category that will probably become more comprehensive as time goes on; Springer’s needs have not yet acquired a great deal of complexity—falls into place around the racing.

In fact, if it wasn’t for the No. 1 plate, it seems unlikely that Jay Springsteen would ever attract anything approaching the attention, adulation and disposable income he now commands. Although he’s intensely competitive, the face he presents to the world is consistently good-natured, affable and rather shy with strangers. When he’s not actually riding his motorcycle sideways down some stretch of blue groove dirt track, he’s either (A) in transit or (B) celebrating life and liberty with the friends he’s acquired in two seasons of almost perpetual motion. Obviously, B is a function of A, and Springer admits that he takes considerable pleasure in being sealed up in his van with a supply of rock ’n roll tapes (along with other small sensory selfindulgences) as he sails from one track to the next.

continued on page 108

continued from page 40

“It’s like gypsies,” he says, savoring the concept. “I travel about nine or 10 months out of the year, and there’s not really much of an off-season.”

When there is, Springsteen goes home for some hunting and fishing, the former being another worry for O’Brien ever since he learned that his national champion managed to put a shot through the calf of his own leg in a hunting mishap after the ’76 season. Springer also takes to the woods from time to time on one of the two Yamaha XT500s he owns (“You probably shouldn’t tell about those,” he informs us). Most recent acquisition in The Springer’s toybox is a matched set of Kawasaki Jet Skis; four of them. The guiding philosophv, apparently, is to stay in motion as much as possible.

As far as the business part of being in motion is concerned. Springer’s plan, augmented by three years’ experience on the tour, is to be tops at his game again in 1978. If he’s successful, he'll be the first rider to take three straight titles since Carroll Resweber won four in a row (1958 through

1961). Jimmy Chann scored three straight—1947. ’48 and '49—and only two other riders have had three-career championships—Joe Leonard and Markel.

The Springer formula for following these tough acts: “I’ll just go out there and do the same thing I did last year and the year before that.”

What he means is, he’ll have fun.— Tony Swan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsThe Troubleshooters

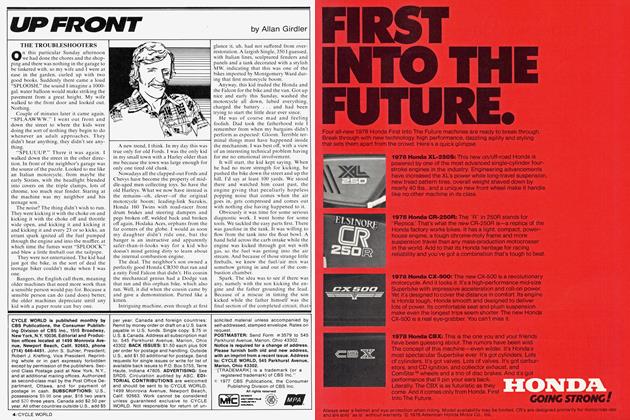

February 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

February 1978 By A.G. -

Roundup

RoundupShort Strokes

February 1978 By Tim Barela -

Competition

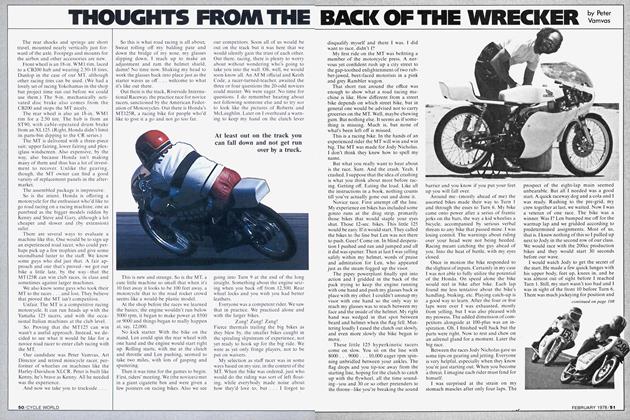

CompetitionThoughts From the Back of the Wrecker

February 1978 By Peter Vamvas -

Features

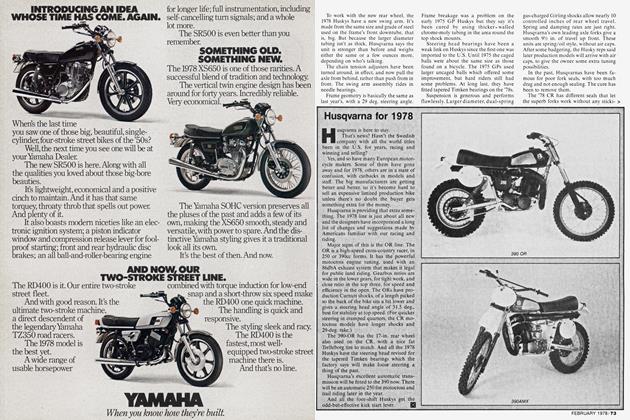

FeaturesHusqvarna For 1978

February 1978