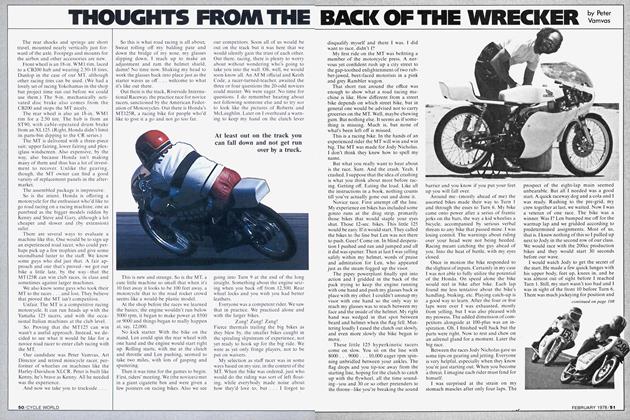

THE TROUBLESHOOTERS

UP FRONT

Allan Girdler

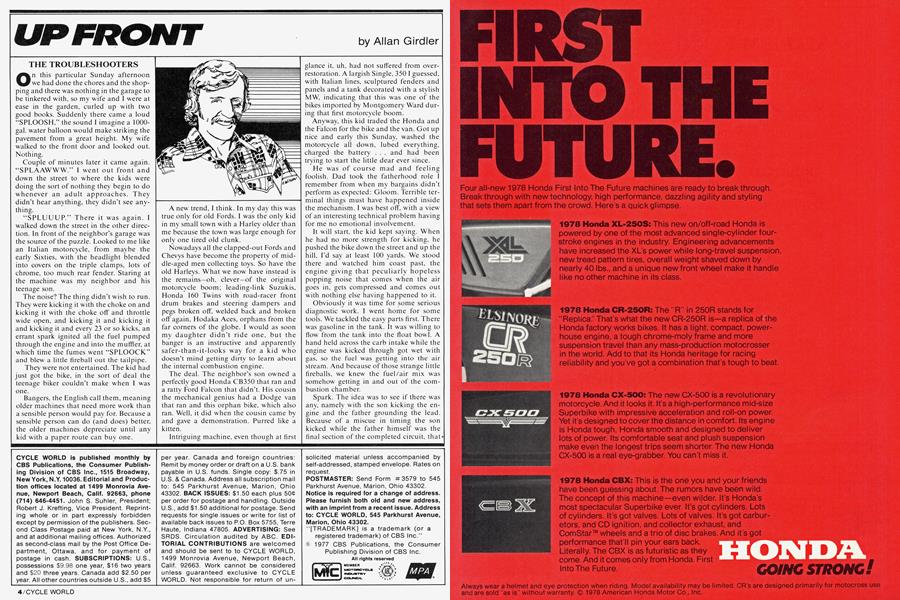

On this particular Sunday afternoon had done the chores and the shopping and there was nothing in the garage to be tinkered with, so my wife and I were at ease in the garden, curled up with two good books. Suddenly there came a loud "SPLOOSH," the sound I imagine a 1000gal. water balloon would make striking the pavement from a great height. My wife walked to the front door and looked out. Nothing.

Couple of minutes later it came again. “SPLAAWWW.” I went out front and down the street to where the kids were doing the sort of nothing they begin to do whenever an adult approaches. They didn’t hear anything, they didn’t see anything.

“SPLUUUP.” There it was again. I walked down the street in the other direction. In front of the neighbor’s garage was the source of the puzzle. Looked to me like an Italian motorcycle, from maybe the early Sixties, with the headlight blended into covers on the triple clamps, lots of chrome, too much rear fender. Staring at the machine was my neighbor and his teenage son.

The noise? The thing didn’t wish to run. They were kicking it with the choke on and kicking it with the choke off and throttle wide open, and kicking it and kicking it and kicking it and every 23 or so kicks, an errant spark ignited all the fuel pumped through the engine and into the muffler, at which time the fumes went “SPLOOCK” and blew a little fireball out the tailpipe.

They were not entertained. The kid had just got the bike, in the sort of deal the teenage biker couldn’t make when I was one.

Bangers, the English call them, meaning older machines that need more work than a sensible person would pay for. Because a sensible person can do (and does) better, the older machines depreciate until any kid with a paper route can buy one.

A new trend, I think. In my day this was true only for old Fords. I was the only kid in my small town with a Harley older than me because the town was large enough for only one tired old clunk.

Nowadays all the clapped-out Fords and Chevys have become the property of middle-aged men collecting toys. So have the old Harleys. What we now have instead is the remains—oh, clever—of the original motorcycle boom; leading-link Suzukis, Honda 160 Twins with road-racer front drum brakes and steering dampers and pegs broken off, welded back and broken off again, Hodaka Aces, orphans from the far corners of the globe. I would as soon my daughter didn’t ride one, but the banger is an instructive and apparently safer-than-it-looks way for a kid who doesn’t mind getting dirty to learn about the internal combustion engine.

The deal. The neighbor’s son owned a perfectly good Honda CB350 that ran and a ratty Ford Falcon that didn’t. His cousin the mechanical genius had a Dodge van that ran and this orphan bike, which also ran. Well, it did when the cousin came by and gave a demonstration. Purred like a kitten.

Intriguing machine, even though at first glance it. uh, had not suffered from overrestoration. A largish Single, 350 I guessed, with Italian lines, sculptured fenders and panels and a tank decorated with a stylish MW, indicating that this was one of the bikes imported by Montgomery Ward during that first motorcycle boom.

Anyway, this kid traded the Honda and the Falcon for the bike and the van. Got up nice and early this Sunday, washed the motorcycle all down, lubed everything, charged the battery . . . and had been trying to start the little dear ever since.

He was of course mad and feeling foolish. Dad took the fatherhood role I remember from when my bargains didn’t perform as expected: Gloom. Terrible terminal things must have happened inside the mechanism. I was best off, with a view7 of an interesting technical problem having for me no emotional involvement.

It will start, the kid kept saying. When he had no more strength for kicking, he pushed the bike down the street and up the hill, I’d say at least 100 yards. We stood there and watched him coast past, the engine giving that peculiarly hopeless popping noise that comes when the air goes in, gets compressed and comes out with nothing else having happened to it.

Obviously it was time for some serious diagnostic work. I went home for some tools. We tackled the easy parts first. There was gasoline in the tank. It was willing to flow from the tank into the float bowl. A hand held across the carb intake while the engine was kicked through got wet with gas, so the fuel was getting into the air stream. And because of those strange little fireballs, we knew the fuel/air mix was somehow getting in and out of the combustion chamber.

Spark. The idea was to see if there was any, namely with the son kicking the engine and the father grounding the lead. Because of a miscue in timing the son kicked while the father himself was the final section of the completed circuit, that» is, he had the spark lead still in his hand.

He jumped about, arms flailing. Good strong spark, I noted calmly.

The plug looked wet, so we wiped it and dried it with a match, a trick that the experts say doesn’t actually do anything. Makes me feel better, though, to see the tip all nice and dry.

More kicking, same lack of engine cooperation. Must be the timing. Oh. I forgot to note that the force needed to kick the engine through, and the puffs from the exhaust pipe and gasps and pops from the intake had persuaded us the engine did have compression and the valves were working.

Peering at the engine up close seemed to indicate the ignition system beneath the left-hand side cover. That meant removing umpteen Allen-head bolts and the entire cover, preceded by the shift lever. Thank goodness the Europeans—I was told later by another neighborhood kid who collects bangers that the Monky Ward motorcycles were actually Güeras, made under contract—do not have the fondness for Phillips heads so prevalent across the other ocean.

Eventually we got to peer solemnly at the points themselves, complete with mechanical advance outboard of the plate with points and adjustment. Not knowing the brand of bike made it hard to know the proper point gap but by carefully cranking the engine through we figured the gap was about 0.015-in., a safe setting. And the points broke just about top dead center, also within reason if not scientific enough for the Grand Prix racers.

In short, an hour or two of carefully checking everything had got us to where we knew everything was fine . . . except that the engine wouldn’t run. All we could do was resolve to learn the make of engine and get a manual so we could find what normal procedure had been violated: If normal expertise won’t work, it’s gotta be an abnormal unit, right?

So the neighborhood skilled mechanic, me, trudged home. Later than I had expected. Supper was being kept warm in the oven.

Postscript: The bright cousin came over next day and found the spark plug itself had broken inside, so the spark was getting to the plug—dad already knew that—but it wasn’t getting to the business end of the plug. The sort of devilish defect anybody could have overlooked, I think.

But I still haven’t gotten around to going over and getting all my tools back.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue