THE DAYTONA 100

The Race Got Shortened, Baker Got a Win and Everybody Else Got Tired of Talking

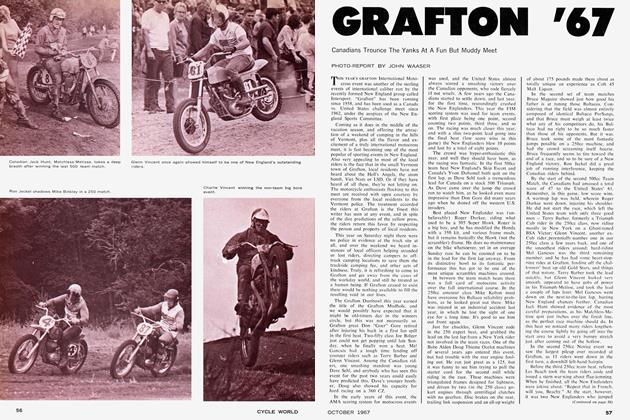

John Waaser

Daytona is always full of surprises, never mind that the actual racing usually follows the form book and the usual winners can find their way to the winner’s stand with their eyes closed.

For the 40th anniversary of the Daytona 200 the weather, the teams, the tire people and the governing bodies all combined, er, efforts, which is not the right word, to give the fans more surprises than even the longtime crowd expected:

The Daytona 200, which is supposed to be 200 miles on Sunday, was actually the Daytona 100.

And the actual competition, the struggle of man against man and men against machines, took place half a day before the bikes rolled onto the starting grid.

Daytona Speedweek 1977 was a week that almost wasn’t.

From the racer’s standpoint, it may well have been one of the shortest Daytona weeks ever. Monday it rained. Scratch Monday. Tuesday, Goodyear discovered a batch of tires which had been improperly cured, and they recalled them for shipment back to the factory. Scratch Tuesday. Wednesday is Amateur Day, so the professionals can scratch Wednesday. Thursday saw a couple of brief practice sessions before it rained again, so scratch Thursday, normally the first day of qualifying. That meant that most riders had to sort their machinery, and qualify, in what was left of Friday after you subtract the novice race and the Superbike Production bash. It was a hectic schedule, made even worse by the fact that by Friday the pits were filling with foreign tourists for whom pit passes had been arranged as part of their excursion, people who held illegitimate press passes, or those who just snuck in with borrowed passes, or no pass at all.

Saturday afternoon brought the running of the Daytona 200, which was held in the tech garage in the pits, and in the lounge area of the Goodyear building.

Before the explanation, some background: Those of us who came to Daytona to watch Gary Nixon and his silver Erv Kanemoto-prepared privateer Yamahas do in the opposition were to be disappointed. This is the third brand of bike Erv has tuned for Gary, and it is significant that they felt a Yamaha was their best chance to beat the factories. Gary fell during practice early in the week, and broke his wrist, thus cutting short his Daytona event and placing his whole European schedule in doubt, though he should be ready to ride by the end of April or middle of May.

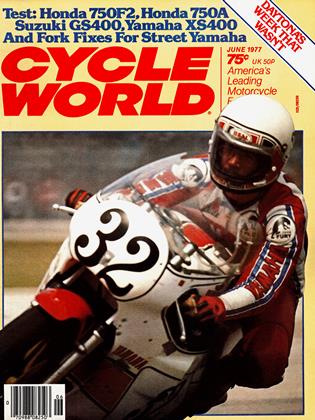

Steve Baker, with his new factory Yamaha ride, set a new track record in qualifying, beating perennial pole-sitter Ken Roberts by nine one-hundredths of a second. Roberts said the track was still a little damp from Thursday’s rain while he was qualifying. They had leaned the mixture to get maximum power for qualifying, and it began to seize as he crossed the line, so it would seem that if they had backed off'about a tenth of a notch, he might have taken the pole. But Robert’s week was like that.

Gary Scott, now sponsored by Evel Knievel in his bid to become Number l as a privateer, has not had luck on his side in the first couple of events this year. Gary needed to do well at Daytona. Most of the point leaders could not be expected to pick up any points here, but Ken Roberts probably would, and Ken could also expect to be a big threat before the end of the year. But all week long Gary suffered minor problems; he was scraping the exhaust pipes so he jacked up the bike, but then it wobbled, so he had to find a compromise. By qualifying time he hadn’t even sorted out his braking points.

Dave Emde had Romero’s old bike. While it was a competitive mount in its day, the new ones brake a whole lot better and charge much harder off the corners.

The best foreigners were the Australians except for Cecotto. Hansford and Sayle were getting around in Yamahalike times. And Australian privateer, Warren Willing, who seemed to be under the wing of Kel Carruthers, qualified 3rd fastest. This was Warren’s third year at Daytona. He picked up his new TZ750 a week before the race, equipped it with air forks, and other modifications, and prepared to ride to win. He felt his two prior experiences at Daytona would be on his side, and he certainly seemed to experience few surprises—at least until the results were posted.

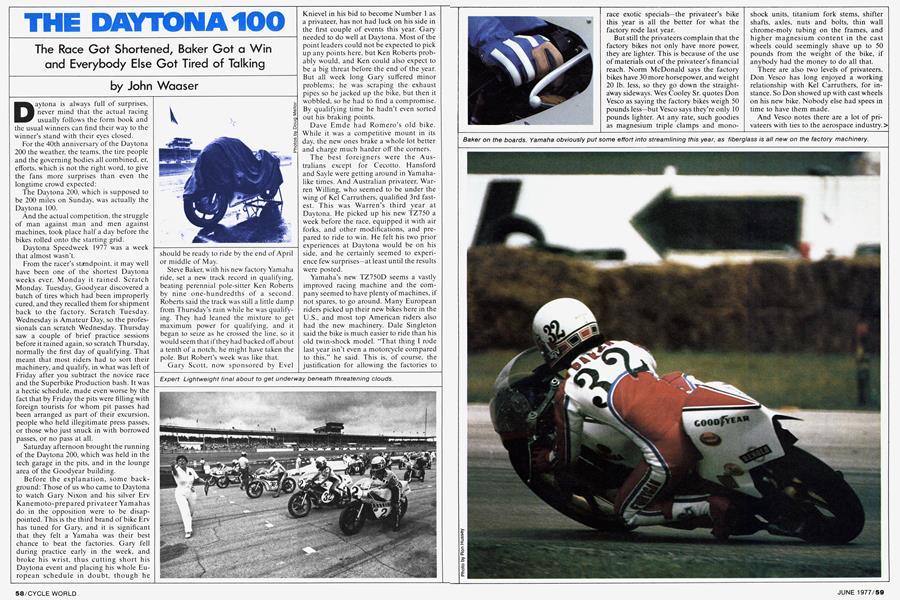

Yamaha’s new TZ750D seems a vastly improved racing machine and the company seemed to have plenty of machines, if not spares, to go around. Many European riders picked up their new bikes here in the U.S., and most top American riders also had the new machinery. Dale Singleton said the bike is much easier to ride than his old twin-shock model. “That thing I rode last year isn’t even a motorcycle compared to this,” he said. This is, of course, the justification for allowing the factories to race exotic specials—the privateer’s bike this year is all the better for what the factory rode last year.

But still the privateers complain that the factory bikes not only have more power, they are lighter. This is because of the use of materials out of the privateer’s financial reach. Norm McDonald says the factory bikes have 30 more horsepower, and weight 20 lb. less, so they go down the straightaway sideways. Wes Cooley Sr. quotes Don Vesco as saying the factory bikes weigh 50 pounds less—but Vesco says they’re only 10 pounds lighter. At any rate, such goodies as magnesium triple clamps and monoshock units, titanium fork stems, shifter shafts, axles, nuts and bolts, thin wall chrome-moly tubing on the frames, and higher magnesium content in the cast wheels could seemingly shave up to 50 pounds from the weight of the bike, if anybody had the money to do all that.

There are also two levels of privateers. Don Vesco has long enjoyed a working relationship with Kel Carruthers, for instance. So Don showed up with cast wheels on his new bike. Nobody else had specs in time to have them made.

And Vesco notes there are a lot of privateers with ties to the aerospace industry. They have things like hard-chromed aluminum monoshock units which even a well-off dealer can’t afford, and a few titanium parts of their own. At any rate, there’s plenty of fuel for both sides of the factory versus privateer argument. Truly the saddest part is that everybody feels they must ride a Yamaha to have any chance at all.

And while Yamaha had a garage rented out to sell spare parts at dealer net prices to any competitor at Daytona, they reportedly only brought eight sets of 1977 brake pucks, and their 40 sets of pistons were sold out the first day.

Having an equal hold on the market was Goodyear. It was uncommonly cold in Florida during the tire testing periods so the tires held up better than they could be expected to under racing conditions. Also the ground had frozen, creating frost heaves on the back stretch. There was talk of a dog-leg on the front straight to slow the riders down, and from Tuesday on there was talk of splitting the race. That would be a hassle of major proportions for most riders, since wheels were not available for the new machines. The only riders who had two wheels for the 1977 bikes were those who had two bikes.

It certainly is a far cry from the day when almost all races, both dirt and pavement, were won on the same Pirelli tires we could chunk the tread off of in moderately zesty street riding.

Michelin could not supply tires to the bulk of the field, and Dunlop has been virtually out of the Daytona 200 tire (oops, tyre) business for years now. So Goodyear was in the position of calling the shots. At one point during a riders meeting, Bob Work, who tunes Steve Baker’s machinery, defended the tire companies, stating it was the fault of the race track, not the tire companies, that the tires wouldn’t last. That certainly put the shoe on the other foot, because the most staunch advocate of running the full 200 miles was none other than track president Bill France.

Work had modified the rear ends of Baker’s and Cecotto’s bikes to eliminate the aluminum cap which fits over the end of the swing arm, on which the chain adjusters pull. He had welded a notched steel plate onto the end of the swing arm—something any privateer could do if he had enough notice. The factory fast guys came to Daytona planning to be ready to change tires. The privateers did not, and by the time they found out they might have to, it was too late to make that kind of modification. Work had practiced tire changing to the point where he was quoting 38 seconds as the time required to change a tire for Baker or Cecotto. Actually, most people doubt he could do it in that length of time under racing conditions, where the brake, axle, chain, and tire are all tqo hot to touch, and besides, the question was academic for anyone other than factory teams, since there were no wheels available.

The first plan was to have everybody black-flagged after 32 laps, then have Goodyear people inspect every tire—if they said you must change, then you would not have been allowed back on the track without new rubber. The restart would have been an hour after the black flag. That seemed like the best plan to the AMA officials. It got Goodyear off their backs, but it put them under fire from the promoter and the privateers. For a while there were rumors that the black flag would be on lap 36, instead of lap 32. That had the Kawasaki people up tight, as it would allow the Yamahas to complete the first part of the race with only one fuel stop while requiring the Kawasakis to make two.

Officials called a riders meeting for Saturday at high noon. Many riders didn’t show up—predominately the factory hotshots. Gary Scott insisted the AMA take attendance and fine the no-shows, per the rulebook. (Gary himself forgot all about a rescheduled meeting at 3 p.m. until we reminded him.) Officials agreed to a rider demand for a warm-up lap before the restart, since many riders would have no opportunity to scuff in tires during practice, because of the lack of spare wheels. Steve McLaughlin was cheered loudly when he mentioned the race changes every time, and the riders don’t know what to prepare for. He suggested pulling a couple of plug leads on the factory bikes.

Charlie Watson explained the AMA had wanted to make only the hot-shots change the tires, but the plan was scrapped by Goodyear honchos, because of the legal climate. Watson raised his voice: “You keep pressuring Yamaha, keep pressuring anybody—Kawasaki, anybody—keep pressuring Goodyear, we ain’t going to have a damn tire to race on; you’ll have no race.” Charlie emphasized that Goodyear, more than anybody, had cooperated with the AMA to give them tires that are safe.

McLaughlin drew another round of applause when he insisted that Goodyear should be at the rider’s meeting to explain why the race should be stopped early, instead of making just the fast guys come in for a change. Somebody mentioned that the FIM rules had to be considered, as well as the AMA rules.

Bob Work arrived and said, “I don’t think it’s just the three riders. Goodyear told us (here he paused, then continued in an ominous voice) they wouldn’t last. But Stevie Baker will go up there if you want 200 miles.”

continued on page 64

Mel Parkhurst, the AMA’s Manager of Professional Competition said, “It has gone past that point—it’s either that or we shorten the race or do something about the middle or Goodyear withdraws all their tires and nobody runs on anything.”

Mike Baldwin, the fiesty little redhead who has made his mark in the production class the last year or so, spoke up. “Eighty percent of the riders came here to run a 200-mile race—maybe even more than that. There’s a small percentage who can’t go the whole race. Now if there’s a 500mile Daytona car race out there, they come in and they change tires four or five times if they have to. And that’s taken into consideration, because for a car it’s a disadvantage. If I can go 200 miles on one set of tires and some of the guys can’t do it, the race goes 200 miles because I came to Florida to go 200 miles.” You had best believe that little dissertation brought thunderous applause from the assembled riders.

That’s the biggest difference between the viewpoints of the AMA and Goodyear, and that of the riders. It does matter to the officials if even one man can’t go the whole 200 miles in reasonable safety. These days, even inherently unsafe sports are expected to be safe, and the courts are likely to find negligence by other than the deceased in the event of a sports death. For the privateers, it’s clearly a tortoise and hare syndrome. The slow guys believe (heck it’s their only chance) that if the fast guy wears out and has to stop, then the slow guy who can keep on going deserves to win the race. Remember the howl the four-stroke devotees put up when they made fuel stops mandatory, even though the two-strokes were the only ones who couldn’t carry enough fuel to go the distance?

The promoter’s viewpoint as expressed by a rider, is “What the hell would happen to the Indy 500 if it was the Indy something else?” The promoter figures he has an institution, and if it’s changed, people won’t come back. You have to admit, the “Daytona 200” has a nicer ring to it than, say, the “Daytona 180.” Journalist Jack Mangus proposed it could be shortened to 200 kilometers, and nobody would know the difference—and there are those who believe that a shorter, tighter race, is more exciting. But again, the privateers feel, perhaps wrongly, that they can outlast the factory bikes, and therefore the length of this race is their only chance.

Charlie Watson kept coming back to the legal aspects. “I’m a little small motorcycle dealer, and I’ve already been confronted with it. We have consumer protection laws.”

Gary Scott mentioned that he was on the AMA National Championship committee, and he had been assured by Bill Boyce that “there will be one green flag, and there will be one checkered flag for this 200 mile race.” The standard AMA argument to this seemed to be, “That was last year.”

Even amid all the sentiment for going the full 200 miles, the riders’ biggest, and most valid complaint, seemed to be they simply had not had enough notice to prepare for a tire change. The AMA had no answer for that one, either. At about that point, Don Brymer walked in. As a promoter, he has a keen interest in knowing just how much input the riders have to the race program—and just how drastically the AMA can get away with changing the program at the last minute. The AMA wisely decided they weren’t getting anywhere this way. They obviously hadn’t expected such a display of rider solidarity against the proposed change. They adjourned the meeting, and called another one for three o’clock—riders only; no mechanics, sponsors, or members of the press.

Ron Pierce had qualified 7th fastest, but a Goodyear man told him, “Ron, I don’t think you’re going to have any trouble at all.” Even after it was all settled Sunday morning. Pierce turned to Mel Parkhurst and asked, “What do you suggest I do? Just not ride, or what?” He wanted to know who he could sue.

At the three o’clock meeting, the referee announced the whole affair would go before an FIM jury. The AMA would be represented by Bill Boyce. Mel Parkhurst. and Charlie Watson. There would be one representative each from Australia. France. Holland. Italy. Japan. England. Belgium, and Canada, and they were still looking for someone from Germany. Somebody mentioned Mexico, w hich only had one rider entered, and everybody broke into a loud guffaw when someone hollered. “What about California?" Not such a dumb question, since California had 2U times as many entries as the largest foreign contingent. It was decided the United States would have two reps, and Charlie declined to suggest a proper place for the riders to go and elect their reps. Elected were Steve McLaughlin and Gary Scott—certainly two of the most adamant advocates of a single. 200-mile race. Steve Baker went along as some sort of special envoy, since he was one of the three riders Goodvear was most concerned about, and he was perfectly willing to ride a single 200-mile race.

McLaughlin felt it would be wise to have some sort of a backup plan—and proposed two 100 mile legs, in case the jury wouldn't buy the 200 miler. But the vocal riders were adamant. “Don't settle for no restart or nothing." said one. Steve had visions of a rider boycott. “The French, the Spanish, the Italians, the Germans, all are on our side." Then they disappeared into the lounge area of the Goodyear garage, where they stayed for about an hour. (It seemed much longer.)

When they emerged. Bill France Jr. took Steve and Gary to the Union 76 garage lounge, in an effort to find out the true feelings of the American riders, and he explained to them that it was the Americans who mattered to him, and nobody else. His own position was plain. He wanted the full 200-mile race.

After the meeting, the jury met in closed session to ponder three alternatives; a 200-mile race, a shortened race, or two 100-mile legs. The original plan, to blackflag the event after 32 of the 52 laps, was scrapped. There was a very real possibility that the fast guys might have to go 200 miles. Warren Willing was not sure he could go 200 miles on one tire, and said he would try to w'ork it out beforehand, that it might depend to some extent on how' it felt out there. Randy Cleek's crew said they would try to have somebody from Goodyear there to inspect the tire during the second gas stop, and if advised changing it, they would do it right then rather than bringing him in for another stop. They agreed that heat would make it difficult to change the tire since the parts w'ould be too hot to touch.

Gregg Hansford thought the riders w'ould stick together better in Europe, and that had this been a European race, there was a good likelihood it would go the 200 miles.

Canadian rep Jim Allen thought the two 100-mile segments would put the event in line with the rest of the world. He said McLaughlin didn't support it, but he clearly thought Steve w'as talking for Steve, not for the American riders. The answer to that, however, is that Steve's feelings were well known, and the riders elected him—so he certainly did speak for the riders. Apparently it was Bill Boyce who originally suggested the two 100-mile segments as the only way around the FIM rules.

continued on page 116

continued from page 67

The decision was not announced to the riders until 6 p.m. on Saturday.

The weather forecast said showers between one and three o’clock Sunday afternoon. In the Sunday morning rider’s meeting. Mel Parkhurst announced, “We have waived the 60 percent rule to go in accordance with the FIM code, which takes precedence in this event, so if we can run off the first 100 miles, the national points, prize money, the whole bit will be paid, and it will be called a race.” Charlie Watson added that they must make an attempt to start the second leg, hence if it rains, the decision to grid for the second leg could be held off as late as 5:30 p.m. Bill France must have been tearing his hair out.

Steve McLaughlin explained the riders had lost their boycott power, largely because the foreign riders wanted their FIM points more than anything else, and the decision reached by the jury would enable the FIM points to be paid if the event went 50 percent of the way. Also, of course some Americans would ride even if the rest called a boycott. Someone mentioned that Steve’s father, whenever he was angry with the promoters, used to talk all the riders into going slow, running a parade, to make a sham of the race. Then when the flag dropped, out front would be John McLaughlin, going full tilt, while the rest of the riders got used to the idea that they’d been had. “What good is it going to do not to ride?” came an anonymous shout.

Mel Parkhurst said the riders have no appreciation for the AMA’s position. Phil McDonald came up with an old New England idea. He suggested running the second leg backwards to even tire wear. Parkhurst grinned widely. But the AAMRR has used this technique often at Loudon, and cited the ability to get an extra couple of races out of a tire as one of the chief advantages of the “Noduol” layout.

Meanwhile, back in the pits, Kenny Roberts’ crew was changing the engine in Kenny’s bike. The full crew plus one extra were working on it. Erv Kanemoto had been pressed into service, such was the rush. Kenny had come in from practice, and while the engine seemed to be runing all right, a plug check showed some metal all over the plugs in cylinders one and two. Kei Carruthers made a prompt decision that there was time to change an engine, but not enough time to look at it, find something wrong with the other one, and then change an engine. Kenny would be running the race on his spare engine.

Riders were cautioned that they must take the checkered flag in each segment to be scored in that segment—that is, unless they crossed the line after the winner had taken the checkered flag, they would receive 80 points for that leg toward their overall score. Moreover, for FIM points, they must complete 75 percent of the laps completed by the leader. The purse would be divided according to overall finish only, with no pay for the finish in each leg, because of the late decision to go with two legs. They were also cautioned to keep racing all the way through Turn One on the cool-down lap, as that is where the timers are, and in the event of a tie in points, if both riders had completed the same number of laps, total elapsed time could be used to break the tie.

continued on page 120

continued from page 116

Also, while AMA rules allow the starter to throw the green flag for th second and third waves at any point between five and 10 seconds after the preceeding wave, at this event, the full 10 seconds would be used. Naturally, the riders in the second and third waves wanted that one reconsidered.

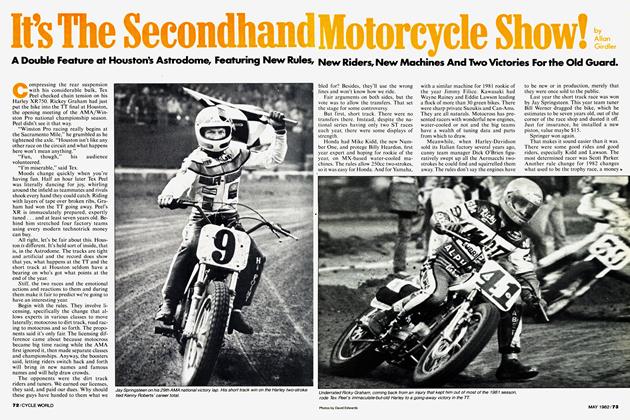

The green flag flew promptly at one o’clock, and Ken Roberts came by just a whisker ahead of Steve Baker on the first lap. While Roberts has twice been the fastest qualifier, he has never won here, and he wanted it. Again on the second lap, it was Ken ahead of Steve. Virginio Ferari pulled out of the pits two laps behind the field, with shift bothers. Skip Aksland came into the pits with a fried clutch, as Roberts and Baker switched the advantage on the next go-round. Australians Gregg Hansford and Warren Willing were running right behind the Roberts/Baker duel. Steve McLaughlin pitted; after having problems sorting his machinery all week, he had walked away from a flat tire in Sunday morning practice, but had to use his turtle bike, and felt it wasn’t worth the effort, so he parked it. Johnny Cecotto came into the pits and retired with an oil leak while running fourth. He explained it wasn’t giving him any traction problems, but David Emde had had traction problems trying to follow the Venezualan. Dave went down in the chicane on the first lap, taking Ron Mass and Mike Baeder with him, presumably because of Cecotto’s oil.

Gary Scott pulled into the pits with a seized engine, thus ending his hopes for a good share of the national points. The high wind was plaguing the riders out there, and many were complaining about heat coming up from the bike.

Steve Baker, in the lead, was one of the first to come in for fuel, and he took on a full load in 3.8 seconds. Roberts came in for his fuel stop a lap or two later, and only took on a partial tank load from a hand-held can. There are reasons for taking on less fuel than the great “tower in the sky.” For one thing, less fuel means less weight—and that weight is up very high, which affects handling, as well as acceleration. But Kenny’s stop took longer by a tenth of a second. Kenny also got a fast Goodyear check.

continued on page 128

continued from page 120

Larry Koop came in for a botched fuel stop. They didn’t even have the gas on the track side of the pit wall when he stopped his bike. Then Skip Aksland came in and they didn’t get his fuel tank cap closed. He had to stop while all of his crew members ran to close it—and the guy holding the gas can dropped it, spilling gas all over pit row.

Three laps from the end, Ron Pierce came in with severe vibration—main bearings, as predicted, said Ron, who indicated the Mack pipes would spin to 12,000 rpm, just like a 250.

Baker won the first leg by 28 seconds, just as light showers began to fall. Roberts, with the spare engine not pulling as strongly as he’d like, experiencing brake problems up front, and bothered enough by heat coming off the bike to actually change fairings between heats, was content to settle for 2nd in that leg, hoping he could win the next leg, and therefore the overall points. Bud Aksland indicated Kenny didn’t like the new aluminum calipers on the front. They save a lot of weight, but Bud felt they distorted when they got hot, thus inducing fade. (Baker loves them, says they give more feel than the old iron brake calipers, which could lock up the wheel.)

Baker indicated he had no problems at all out there, except for being bothered by the heat, and Bob Work indicated Steve’s tire could probably have gone the full 200 miles. Wes Cooley said he had maybe half a millimeter of tire wear, and took the opportunity to call for a minimum weight rule, minimum quantity of 200 bikes available for the public, and a claiming rule for the entire motorcycle with the price set at $500 over factory retail.

Hansford’s and Willing’s bikes were not running as well as they had in practice, but by now it was raining so hard that everybody knew there would be no second leg. Hansford’s crew felt that 4th place was a creditable finish, and it certainly was far enough forward to break up the Yamaha string.

At 4:30 they made official what everybody had known all along—the track could not be made ready for the second leg after dark, and so the race would be called at the 100-mile mark. They posted the results, and 6th-place Warren Willing found himself listed as 23rd. It turned out his own scorer had missed him the first lap, and the AMA score keepers had all missed him as well. Not one scorer showed him completing the first lap, but all the AMA scorers had blanks shown in about the area where he was running, and enough people came to his aide that the officials credited him with his deserved 6th position. “Whoever decided to use three-digit numbers for the European riders really screwed up,” said Yamaha’s Ken Clark.

Only three foreign riders have ever won the Daytona 200, and it was won this year by an American. The foreigners did dominate the top 10 positions here, so Clark may have a point.

In a written “Statement from Race Officials,” dated Saturday, March 12, 1977, it is stated that, “Officials said that the format of 200 consecutive miles will be resumed in 1978.” In view of this year’s performance, that promise seems perhaps a bit empty, so I asked Mel Parkhurst, “Who decided they’re going to go with 200 miles next year?”

“Promoter’s Clause . . .” replied Mel. “We agreed with that just to get this (bleep bleep) race run off. I’m sure it will go 200 one way or the other next year. There’s no reason we can’t get set up to do the same thing the cars do. If a guy can’t go the distance on tires, then he’ll just have to prepare to come in and change them.”

Kenny Roberts had another car-like suggestion which seemed out of place for him. He advocated reducing carburetor size to 28 mm maximum.

If you look at Parkhurst’s statement carefully, you’ll see two possibilities. First, that the AMA is prepared to pull a carbon copy of this year’s scene again next year. And second, that they’re prepared to face the problem like men, and deal with it in a manner satisfactory to everyone. [5]