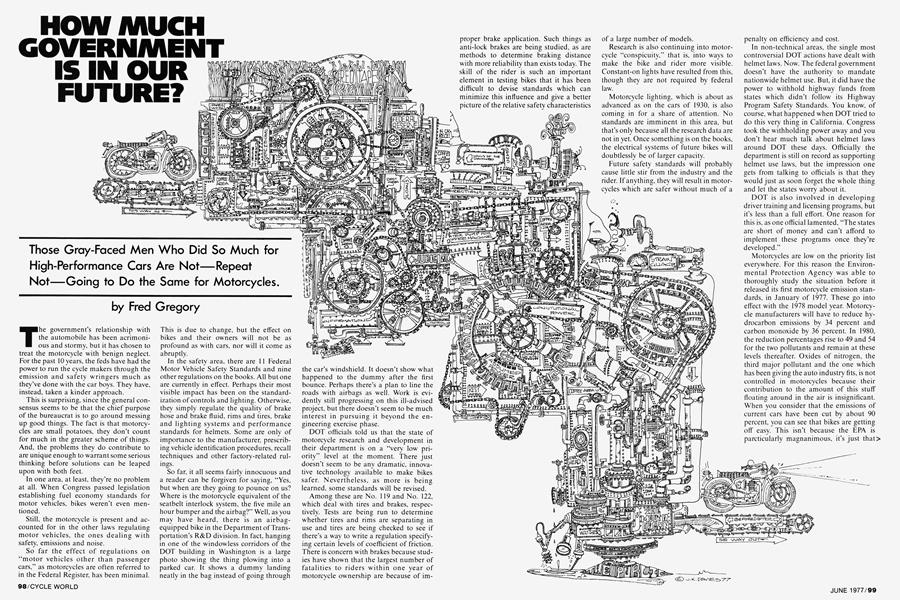

HOW MUCH GOVERNMENT IS IN OUR FUTURE?

Those Gray-Faced Men Who Did So Much for High-Performance Cars Are Not—Repeat Not—Going to Do the Same for Motorcycles.

Fred Gregory

The government's relationship with the automobile has been acrimonious and stormy, but it has chosen to treat the motorcycle with benign neglect. For the past 10 years, the feds have had the power to run the cycle makers through the emission and safety wringers much as they’ve done with the car boys. They have, instead, taken a kinder approach.

This is surprising, since the general consensus seems to be that the chief purpose of the bureaucrat is to go around messing up good things. The fact is that motorcycles are small potatoes, they don’t count for much in the greater scheme of things. And, the problems they do contribute to are unique enough to warrant some serious thinking before solutions can be leaped upon with both feet.

In one area, at least, they’re no problem at all. When Congress passed legislation establishing fuel economy standards for motor vehicles, bikes weren’t even mentioned.

Still, the motorcycle is present and accounted for in the other laws regulating motor vehicles, the ones dealing with safety, emissions and noise.

So far the effect of regulations on “motor vehicles other than passenger cars,” as motorcycles are often referred to in the Federal Register, has been minimal.

This is due to change, but the effect on bikes and their owners will not be as profound as with cars, nor will it come as abruptly.

In the safety area, there are 11 Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards and nine other regulations on the books. All but one are currently in effect. Perhaps their most visible impact has been on the standardization of controls and lighting. Otherwise, they simply regulate the quality of brake hose and brake fluid, rims and tires, brake and lighting systems and performance standards for helmets. Some are only of importance to the manufacturer, prescribing vehicle identification procedures, recall techniques and other factory-related rulings.

So far, it all seems fairly innocuous and a reader can be forgiven for saying, “Yes, but when are they going to pounce on us? Where is the motorcycle equivalent of the seatbelt interlock system, the five mile an hour bumper and the airbag?” Well, as you may have heard, there is an airbagequipped bike in the Department of Transportation’s R&D division. In fact, hanging in one of the windowless corridors of the DOT building in Washington is a large photo showing the thing plowing into a parked car. It shows a dummy landing neatly in the bag instead of going through the car’s windshield. It doesn’t show what happened to the dummy after the first bounce. Perhaps there’s a plan to line the roads with airbags as well. Work is evidently still progressing on this ill-advised project, but there doesn’t seem to be much interest in pursuing it beyond the engineering exercise phase.

DOT officials told us that the state of motorcycle research and development in their department is on a “very low priority” level at the moment. There just doesn’t seem to be any dramatic, innovative technology available to make bikes safer. Nevertheless, as more is being learned, some standards will be revised.

Among these are No. 119 and No. 122, which deal with tires and brakes, respectively. Tests are being run to determine whether tires and rims are separating in use and tires are being checked to see if there’s a way to write a regulation specifying certain levels of coefficient of friction. There is concern with brakes because studies have shown that the largest number of fatalities to riders within one year of motorcycle ownership are because of improper brake application. Such things as anti-lock brakes are being studied, as are methods to determine braking distance with more reliability than exists today. The skill of the rider is such an important element in testing bikes that it has been difficult to devise standards which can minimize this influence and give a better picture of the relative safety characteristics of a large number of models.

Research is also continuing into motorcycle “conspicuity,” that is, into ways to make the bike and rider more visible. Constant-on lights have resulted from this, though they are not required by federal law.

Motorcycle lighting, which is about as advanced as on the cars of 1930, is also coming in for a share of attention. No standards are imminent in this area, but that’s only because all the research data are not in yet. Once something is on the books, the electrical systems of future bikes will doubtlessly be of larger capacity.

Future safety standards will probably cause little stir from the industry and the rider. If anything, they will result in motorcycles which are safer without much of a penalty on efficiency and cost.

In non-technical areas, the single most controversial DOT actions have dealt with helmet laws. Now. The federal government doesn't have the authority to mandate nationwide helmet use. But, it did have the power to withhold highway funds from states which didn't follow its Highway Program Safety Standards. You know, of course, what happened when DOT tried to do this very thing in California. Congress took the withholding power away and you don't hear much talk about helmet laws around DOT these days. Officially the department is still on record as supporting helmet use laws, but the impression one gets from talking to officials is that they would just as soon forget the whole thing and let the states worry about it.

DOT is also involved in developing driver training and licensing programs, but it's less than a full effort. One reason for this is, as one official lamented, "The states are short of money and can't afford to implement these programs once they're developed."

Motorcycles are low on the priority list everywhere. For this reason the Environ mental Protection Agency was able to thoroughly study the situation before it released its first motorcycle emission stan dards, in January of 1977. These go into effect with the 1978 model year. Motorcy cle manufacturers will have to reduce hy drocarbon emissions by 34 percent and carbon monoxide by 36 percent. In 1980, the reduction percentages rise to 49 and 54 for the two pollutants and remain at these levels thereafter. Oxides of nitrogen, the third major pollutant and the one which has been giving the auto industry fits, is not controlled in motorcycles because their contribution to the amount of this stuff floating around in the air is insignificant. When you consider that the emissions of current cars have been cut by about 90 percent, you can see that bikes are getting off easy. This isn't because the EPA is parcticularly magnanimous, it's just that the motorcycle is not that big a part of the problem. They’ve also taken into consideration the difficulties of “packaging” emission gear on bikes. It’s one thing to tuck a catalytic converter beneath the floorboard of a sedan; putting one of the high-temperature devices on a motorcycle is something else again.

As it is, relying on data provided by manufacturers, the EPA figures that the cleanup will cost about $47 per bike, on the average.

If anything, future safety standards will result in motorcycles which are safer without much of a penalty on efficiency and cost.

As with autos, an emission test will have to be met before a motorcycle can be sold in this country. With one notable exception. manufacturers will be able to make bikes which pass this test by relying on “relatively unsophisticated” technology. The EPA speculates that improvements in fuel metering, porting and ignitions will be all that’s required.

The exception is the two-stroke motorcycle. There’s no way these will pass the test. In a couple of years, they’ll be just a memory. This holds true for on-the-road or dual purpose two strokes; you’ll still be able to buy them for off-road use.

The EPA is also in charge of regulating noise, but this is being studied and it will be some time before final rulings are published. Consequently, it is difficult to predict at this point what effect there will be on motorcycle technology and cost.

Another area where the federal government is involved is land use policy. The Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management are both under a mandate to develop land use strategies. Their final decisions will certainly affect off-road riders. The American Motorcyclist Association has been active in presenting the rider's case here, and there are indications that at least these interests won’t be ignored.

“Yes, but when are they going to pounce on us?”

After years of covering the government’s often bitter relationship with the auto industry, I was pleasantly surprised that the same lack of cooperation is not evident with regard to dealings among the feds and the cycle business. The people in Washington with whom I spoke were unanimous in their praise for the cooperation they’ve had from the motorcycle industry. They found a positive attitude and a willingness to provide data and information that is rare in such dealings. This, it seems to me, has helped get rules and regulations which appear to be reasonable and fair. When this happens, it is only to the benefit of the well being and the pocketbook of the consumer.