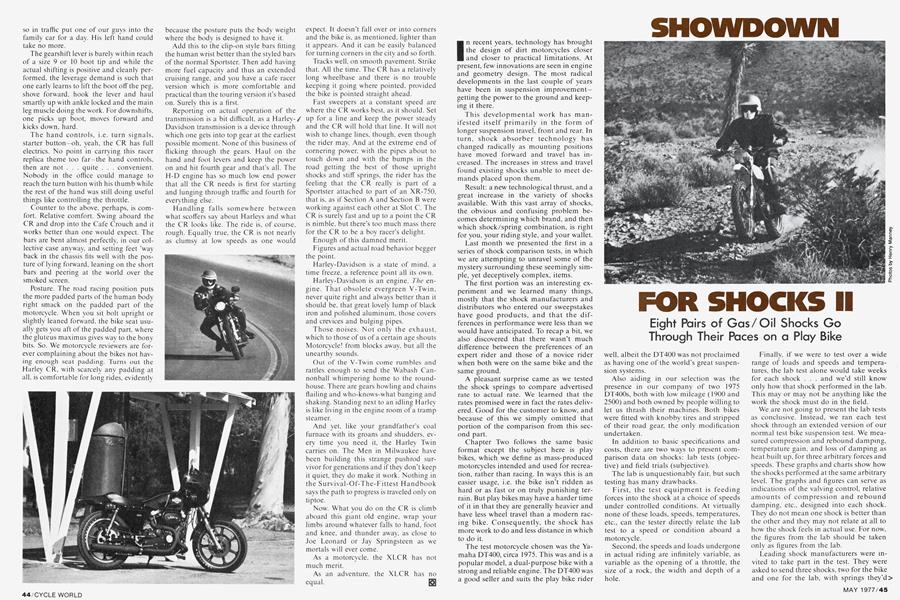

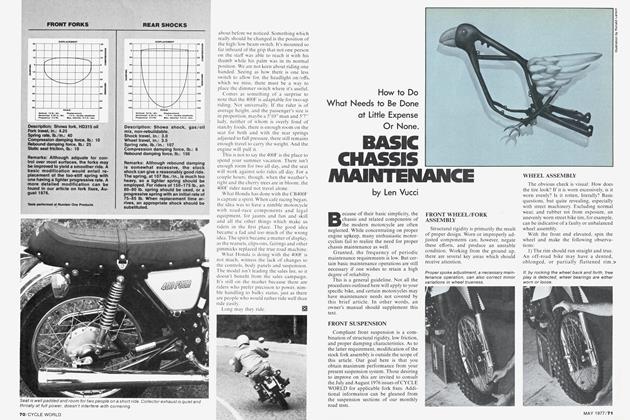

SHOWDOWN FOR SHOCKS II

Eight Pairs of Gas/ Oil Shocks Go Through Their Paces on a Play Bike

In recent years, technology has brought the design of dirt motorcycles closer and closer to practical limitations. At present, few innovations are seen in engine and geometry design. The most radical developments in the last couple of years have been in suspension improvement-getting the power to the ground and keeping it there.

This developmental work has manifested itself primarily in the form of longer suspension travel, front and rear. In turn, shock absorber technology has changed radically as mounting positions have moved forward and travel has increased. The increases in stress and travel found existing shocks unable to meet demands placed upon them.

Result: a new technological thrust, and a great increase in the variety of shocks available. With this vast array of shocks, the obvious and confusing problem becomes determining which brand, and then which shock/spring combination, is right for you, your riding style, and your wallet.

Last month we presented the first in a series of shock comparison tests, in which we are attempting to unravel some of the mystery surrounding these seemingly simple, yet deceptively complex, items.

The first portion was an interesting experiment and we learned many things, mostly that the shock manufacturers and distributors who entered our sweepstakes have good products, and that the differences in performance were less than we would have anticipated. To recap a bit, we also discovered that there wasn’t much difference between the preferences of an expert rider and those of a novice rider when both were on the same bike and the same ground.

A pleasant surprise came as we tested the shock springs to compare advertised rate to actual rate. We learned that the rates promised were in fact the rates delivered. Good for the customer to know, and because of this we simply omitted that portion of the comparison from this second part.

Chapter Two follows the same basic format except the subject here is play bikes, which we define as mass-produced motorcycles intended and used for recreation, rather than racing. In ways this is an easier usage, i.e. the bike isn’t ridden as hard or as fast or on truly punishing terrain. But play bikes may have a harder time of it in that they are generally heavier and have less wheel travel than a modern racing bike. Consequently, the shock has more work to do and less distance in which to do it.

The test motorcycle chosen was the Yamaha DT400, circa 1975. This was and is a popular model, a dual-purpose bike with a strong and reliable engine. The DT400 was a good seller and suits the play bike rider well, albeit the DT400 was not proclaimed as having one of the world’s great suspension systems.

Also aiding in our selection was the presence in our company of two 1975 DT400s, both with low mileage (1900 and 2500) and both owned by people willing to let us thrash their machines. Both bikes were fitted with knobby tires and stripped of their road gear, the only modification undertaken.

In addition to basic specifications and costs, there are two ways to present comparison data on shocks: lab tests (objective) and field trials (subjective).

The lab is unquestionably fair, but such testing has many drawbacks.

First, the test equipment is feeding forces into the shock at a choice of speeds under controlled conditions. At virtually none of these loads, speeds, temperatures, etc., can the tester directly relate the lab test to a speed or condition aboard a motorcycle.

Second, the speeds and loads undergone in actual riding are infinitely variable, as variable as the opening of a throttle, the size of a rock, the width and depth of a hole.

Finally, if we were to test over a wide range of loads and speeds and temperatures, the lab test alone would take weeks for each shock . . . and we’d still know only how that shock performed in the lab. This may or may not be anything like the work the shock must do in the field.

We are not going to present the lab tests as conclusive. Instead, we ran each test shock through an extended version of our normal test bike suspension test. We measured compression and rebound damping, temperature gain, and loss of damping as heat built up. for three arbitrary forces and speeds. These graphs and charts show how the shocks performed at the same arbitrary level. The graphs and figures can serve as indications of the valving control, relative amounts of compression and rebound damping, etc., designed into each shock. They do not mean one shock is better than the other and they may not relate at all to how the shock feels in actual use. For now, the figures from the lab should be taken only as figures from the lab.

Leading shock manufacturers were invited to take part in the test. They were asked to send three shocks, two for the bike and one for the lab, with springs they’d > recommend for the Yamaha DT with a medium weight rider.

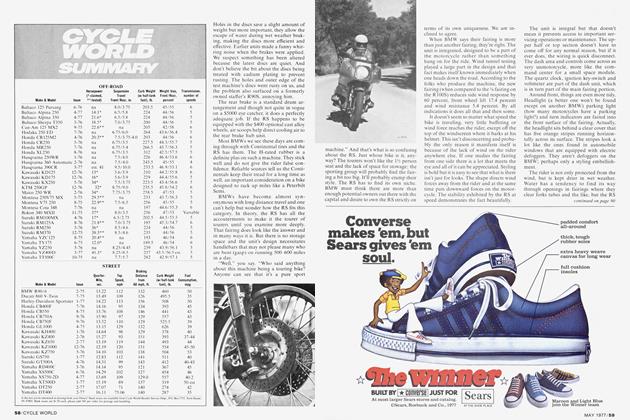

Nine firms accepted the invitation. The makes, models and specifications, are as follows:

ARNACO LTR-1

Arnaco, Inc. 13431 Saticoy St. North Hollywood, Calif. 91605 Shock price: $109.95/pr. Spring price: 23.95/pr. Rebuildable? yes Construction: The Arnaco is a single-wall design. Shock body and spring end are machined from billet aluminum. Internally, a pressurized damping fluid/nitrogen mixture is used in conjunction with a patented system of valving. Travel: 3.5 in. (89 mm) Pre-load adjustment? yes Piston rod diameter: 0.562 in. (14.3 mm) Remarks: Includes a complete selection of spacers and hardware, and a special tool for extremely easy preload adjustments. Offered in 11-inch to 17-inch lengths, the shocks are designed for specific motorcycle applications.

GIRLING 52928E

Lucas Industries North America Two Northfield Plaza Troy, Mich. 48090 Shock price: $71.50/pr. Spring price: 12.20/pr. Rebuildable? no Construction: Girling gas shocks are steel single-wall type. They utilize a pressurized oil/nitrogen mixture. Travel: 3.75 in. (95 mm) Pre-load adjustment? yes Piston rod diameter: 0.488 in. (12.4 mm) Remarks: The quoted price includes a necessary mounting kit. This kit includes bushings and spring retainers. Preload can be adjusted in 10 mm increments by using multiple retainers.

KONI 76F-1250SP1

Bikoni Ltd. 150 Green St. Hackensack, N.J. 07601 Shock price: $68.00/pr. Spring price: 12.00/pr. Rebuildable? yes Construction: The Koni is a steel singlewall shock, utilizing a gas/oil mixture for compression displacement. The footvalve of the shock is externally adjustable. Rebound damping may be tuned, or a compensation made for wear. Travel: 3.25 in. (83 mm) Pre-load adjustment? yes Piston rod diameter: 0.461 in. (11.7 mm) Remarks: The Koni shocks were tested in the minimum damping position. Rebound damping is approximately double for the maximum setting.

MICKEY THOMPSON 36-320-H1

Mickey Thompson Products 2701 East Anaheim St. Wilmington, Calif. 90744 Shock Price: $60.00/pr.* Spring price: $12.00/pr. Rebuildable? no Construction: M/T shocks are single-wall DeCarbon type. It is of the single-tube variety, and is charged to a pressure of 24 atmospheres (350 psi.). Travel: 3.5 in. (89 mm) Pre-load adjustment? yes Piston rod diameter: 0.410 in. (10.4 mm) Remarks: Four damping rates are available from H1 (soft) to H4 (hard). Heim (swivel) ends are available for an additional $5.00/pr. ^Direct mail order price.

MULHOLLAND LTG 130F

Mulholland (Interpart) 230 W. Rosecrans Ave. Gardena, Calif. 90248 Shock price: $89.95/pr. Spring price: 27.95/pr. Rebuildable? yes Construction: The shock body is a steel dual-wall design. Gas is contained within a bladder located between the inner and outer walls. A finned aluminum heat sink is fitted to the lower body for additional cooling. Travel: 4.0 in. (102 mm) Pre-load adjustment? no Piston rod diameter: 0.482 in. (12.25 mm) Remarks: The LTG series shock is available in two damping rates. In addition to rebuilding kits, replacement components may be purchased which allow damping rates to be changed by the user.

NUMBER ONE PRODUCTS FP3301-S

Number One Products 4931 N. Encinita Ave. Temple City, Calif. 91780 Shock price: $69.95/pr. Spring price: 24.95/pr. Rebuildable? yes Construction: Number One shocks have steel bodies, and are dual-wall construction. A bladder filled with freon gas is located between the inner and outer walls for compression displacement. An aluminum coolor is provided for heat dissipation. Travel: 4.0 in. (102 mm) Pre-load adjustment? yes Piston rod diameter: 0.492 in. (12.5 mm) Remarks: Shocks can be ordered in three damping rates: soft, medium or firm. We tested the soft pair. Besides offering rebuilding kits, the factory makes available components for altering original damping rates.

RED WING G-330-85 (medium)

Marubeni America 200 Park Ave., New York, N.Y. 10017 Shock price: $61.90/pr. Spring price: 27.95/pr. Rebuildable? no Construction: The Red Wing is a steel body single-tube DeCarbon type shock. Nitrogen gas, at 18 atmospheres (265 psi), is segregated from the oil by the floating piston. Travel: 3.4 in. (86 mm) Pre-load adjustment? yes Piston rod diameter: 0.488 in. (12.4 mm) Remarks: Damping is available in three rates: soft, medium, and hard.

S&W H525-3

S&W Engineered Products 2617 Woodland Anaheim, Calif. 92801 Shock price: $63.90/pr. Spring price: 14.10/pr. Rebuildable: no Construction: S&W shocks are steel double-wall units. They utilize a freon-filled nylon cell located in the cavity between inner and outer walls for compression displacement. Travel: 4.1 in. (104 mm) Pre-load adjustment? yes Piston rod diameter: 0.488 in. (12.4 mm) Remarks: S&W’s 1976 model shocks were used for this test. An improved 1977 version should be currently available.

WORKS PERFORMANCE

Works Performance Products 20970 Knapp St. Chatsworth, Calif. 91311 Shock price: $114.50/pr. with springs. Rebuildable? yes Construction: Works Performance shocks utilize a steel single-wall body, upon which is cast a finned aluminum heat sink/top mount. Compression displacement is handled by the nitrogen/oil mixture. Travel: 5.0 in. (127 mm) Pre-load adjustment? no Piston rod diameter: 0.500 in. (12.7 mm) Remarks: Works Performance shocks are not listed by model numbers. Instead, motorcycle model and use and rider weight should be given. The proper shock will then be supplied. Shocks can also be custom built for a particular need.

FIELD TRIALS

For our first shock evaluation test last month, we used an expert desert racer for our primary test rider. Because we were testing racing shocks, we felt this would yield the most valid results.

For this test of play bike shocks, we used two riders whose abilities we shall term middle-of-the-road. We think most people who seriously ride this type of bike fall in the range between novice and expert. Utilizing riders within this range should give conclusions that would be more applicable to the majority than if we again relied on an expert.

Our riders are of comparable ability, but one rides faster than the other, by choice. > We felt that if their inputs correlated, this would further increase the populace to whom the results would be applicable.

The test was run over the same six-mile course utilized for last month’s test. This course contains a potpourri of terrain, very representative of just about anything one would encounter.

In order to minimize subjectivity, the riders were not allowed to discuss anything regarding the testing with each other until after its completion.

Each rider rode the course on the stock shocks. This was done to familiarize him with the course so that he could concentrate on the performance of the shocks without having to concentrate on where he is going. This also served to give him some base reference point for his evaluation.

No sooner had the two riders returned from their exploratory runs than the rest of the crew ran into a problem all too familiar with those of us who buy new things for our bikes: Some of the shocks didn’t quite fit the motorcycles. Two were not the same length as the others, or the stock shocks (about which more later). Five of the pairs on hand had mounting bushings and sleeves wider than the Yamaha mounting brackets.

This is understandable, as there are literally hundreds of applications for a basic shock type. What the original manufacturers and aftermarket firms do is build, buy and sell general models in various dimensions and damping rates.

This is not to criticize. This is to say economics play a part here. If the makers couldn’t do this, there would be far fewer firms in business and their products would cost much more than they do.

In this case, representatives of three firms, Arnaco, Koni and S&W, were present for the field trials. They expected to observe: instead, they spent the morning shaving shock bushings and sleeves.

The Arnaco, Mulholland, S&W and Works Performance shocks bolted right on. The Mickey Thompsons could not be used. Their mounting eyes were wider than the Yamaha brackets and nothing short of a grinder would have been able to trim them to fit. The M/T shocks were put back in the truck. The other four pairs were worked on and used.

As a consumer note, the shock suppliers were aware of this problem and they do what they can. Most shocks are sold with installation kits, consisting of washers, for spacing, and sleeves to allow use of different size stock bolts within the same bushing.

RIDER REACTIONS

When the riders knew where to go, a new pair of shocks and springs was put on each bike and they rode the course again, as quickly as felt comfortable. At the end of each loop they dictated their reactions, traded bikes, and went around again, until they had ridden each of the eight pairs of shocks.

Because the order of testing is bound to influence reactions, we’ll present rider comments in the order the shocks were tested.

ARNACO LTR-1

Slow: “The first reaction for me was how much better these shocks are than the stock shocks. I guess I was going faster, too. and the front end seemed overworked; 1 didn’t notice that with the stock rear shocks. There was good wheel control and I went up the hillclimb with no trouble, sitting down.”

Fast: “These shocks are a good match for the bike. The rear wheel stays on the ground through all types of terrain. They work especially well in the whoop-dees and the bike was stable through the rocky section. I like them.”

S&W

Slow: “They felt softer and more comfortable than the first pair but the rear wheel seemed to return to the ground slowly and it kicked a bit under power. Front end jumping like mad. I think anybody who puts new shocks on one of these better go for a fork kit at the same time.”

Fast: “These work well in all situations but the inadequacy of the stock front end was really noticeable. They tended to kick the back end up a bit. If the forks were as firm as they should be, the shocks would work fine.”

WORKS PERFORMANCE

Slow: “The firmest so far. You can feel the stutter bumps more and they’re not as comfortable. They do land well, but the ride is just plain hard.”

Fast: “These give a harsh ride and the suspension never really worked. The back end was loose and the front was twitchy, especially in the sand wash. When I hit some whoops at speed the back wheel kicked ’way high. These just don’t work on this bike.”

Note: The shocks tested on this occasion were 14-in. long, fully F/2-in. longer than stock. They changed the bike’s geometry, which is why the handling deteriorated.

Works Performance has no catalog. Instead, the customer tells the company what bike he has and the company sends the shock they recommend. Before the field > tests, we asked Works Performance if they truly wanted to submit this longer model shock and they said yes, they did, that they feel the extra travel is worth the geometry changes. We don’t agree.

KONI

Slow: “They felt the stiffest so far. I could especially feel the stutter bumps and I think they gave me the hardest workout yet. They do handle well, though.”

Fast: “They skated around and felt loose on the hard, flat sections. The shocks seemed to be loosening up, as if they were breaking in. A softer spring probably would make them work right.”

MULHOLLAND LTG

Slow: “They feel firm but not as much as some of the earlier shocks. The front and rear wheels seem to be bouncing but working together, if you can make anything from that. They seemed to bottom where the others didn’t and I felt like the bike wasn’t steering as well.”

Fast: “They work OK going slow but seemed too soft at higher speeds. The back end would bottom and then would kick up pretty hard. They were just too soft for going fast on anything except the flat sections. Felt like the back end was packing down.”

NUMBER ONE PRODUCTS

Slow: “Oh boy. I didn’t know what the hell was going on. Felt not too bad at first but when I got into the sand wash I couldn’t steer. Slapping the tank all over the place. How can the shocks make a change like that? When I was back on hard ground the bike steered fine except the rear wheel was kicking up and kicking sideways. What is this?”

Full Stop. Inspection revealed the shocks had been mounted with no preload. The rear end sagged and was extremely low, resulting in another geometry change. The preload was set correctly and the second rider set out.

Fast: “These felt soft at low speeds and I thought they'd bottom as I went faster. But when I did, the shocks kept up and worked well for the whole loop. They were especially stable on the whoop-de-doos. I could get the front wheel in the air, and landing hard on the back still didn’t bottom them.”

So. Another note here, namely that proper assembly and set-up can make as much difference as the shocks themselves.

GIRLING

Slow: “You may not want to tell me this, but ... are these shocks taller? The bike feels high and much firmer. Steered fine, jumps better than that. The ride is rough, but these shocks work.”

(The Girlings were in fact longer than the stock shocks, but they weren’t as long as the Works Performance shocks. What this rider was actually noting was the difference in height between the tall Girlings and the Number Ones without preload.)

Fast: “Really hard at low speeds. They feel more like struts than shocks. The rear end kicked at all speeds but not quite as badly at high speed. Steering felt too quick.”

(More of the same, in that both sets of longer-than-stock shocks affected the DT’s handling to the point it was hard to separate the shock action from the geometry change.)

RED WING

Slow: “The rear kicks a little and the back wheel floats a little. Seemed like a good ride in a straight line, with good control and good on the stutter bumps, but it seemed like it was hopping too much on the big bumps.”

Fast: “Whew! Those were really kickers, the hardest yet. I don’t think the suspension moved much and I felt every bump and rock the back wheel hit. These probably would work on a more radical bike, but not on a play bike like this.”

CONCLUSIONS

There are two sets of conclusions, general and specific, and even the specific findings are pretty general.

On the high end of the subjective reactions are Arnaco and S&W, because both riders liked them. Number One should be in the top, too; when properly assembled, they did as well. Works Performance and Girling seemed handicapped by their extra length, so the comments on them apply to something other than damping and control. For the rest, our two riders believed they were too firm or soft. Both men weigh 150 lb., by the way, so a rider who weighs more or less, or whose play bike is heavier or lighter than the DT400, can make allowances for circumstances.

Looking back now at the lab tests, the chart shows Arnaco, Number One and S&W shocks to have fairly similar readings in our sample checks. Perhaps as important, their spring rates are close; Arnaco and S&W supplied progressive springs with identical rates and Number One went slightly softer on the soft end and harder on the firm end.

Mind, these are fallible people. Note that one rider said the Koni springs were too stiff, while the Konis had the softest springs in the group.

Getting even more personal and subjective, for what it’s worth, the S&W shocks and springs were appropriated by a member of the editorial staff. And the owner of one of the DTs was promised some good shocks in trade for the use of his scooter. He’ll try the Arnacos and the Number Ones and pick the pair that suits him best.

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

Take your time in ordering shocks. Be sure first that the extended length is the same as stock. Aftermarket shocks will> improve handling. Longer or shorter shocks will modify handling. There are good reasons for doing this, but such changes should not be done until and unless the modifier has a good idea of what changes he’s after and how to get them.

ARNACO

GIRLING

KONI

MICKEY THOMPSON

MULHOLLAND

NUMBER ONE

RED WING

s&w

WORKS PERFORMANCE

Unless you have experience in this field, we’d suggest first removing one of the old shocks and measuring its length, center of mount to center of mount. If you have 12‘/2-in. shocks, replace them with 12'/2-in. shocks.

While you’re measuring, check the width of the mounting bracket. Be ready to pad the new bushing with washers, or to file down the bushing. In either case, don’t plan on fitting the new shocks out in the woods. Do so at home, where the tools are.

Consider experimenting with spring rates. Because play bikes go everywhere, they will benefit from having a soft initial ride on road or trail, and a stiff spring at the end of travel, to handle those drops and jumps. Many shock manufacturers offer either single rate or progressive springs. If your brand does this, take the progressives.

Either way, spring rate has an important effect on shock performance and on handling. Shocks are expensive. Springs aren’t. Begin with the recommended rate and be thinking about going one step harder or softer, whichever way the ride feels to you. Making this even easier, we’re told some shops will let you trade or even try out new springs until you have some you like.

If there is a winner in this comparison test, it is all of us. The clearest reaction from the test riders was how much better the bikes felt with good shocks. Every shock in this group was better than the factory-fitted units, and the gap from original to aftermarket was wider than was the gap between any of the test units. Pick a reputable brand and you’ll have a better motorcycle. Bí