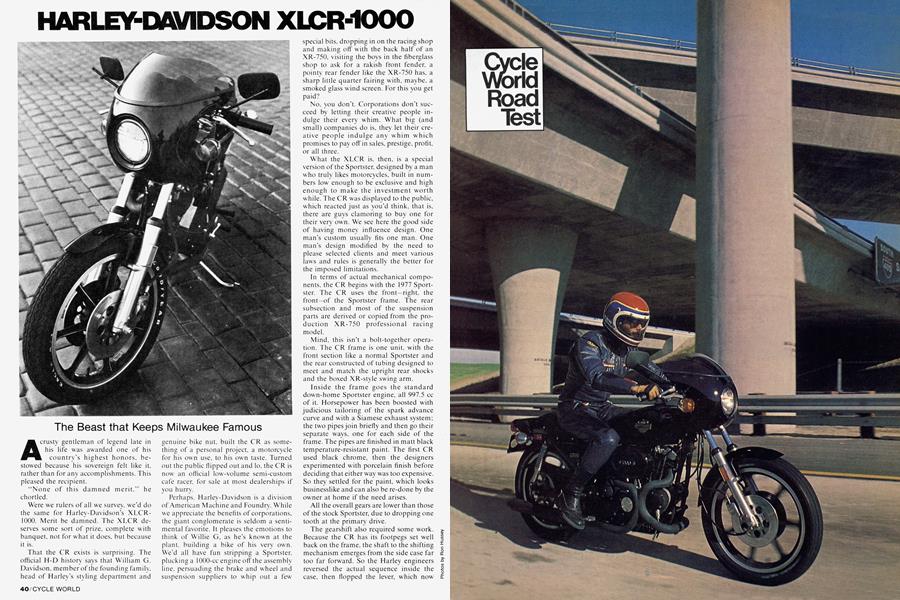

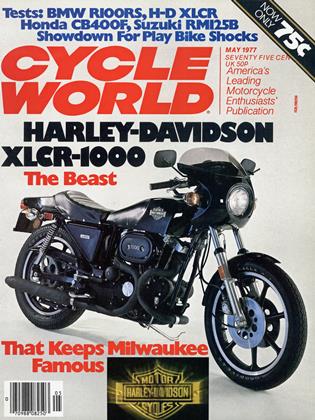

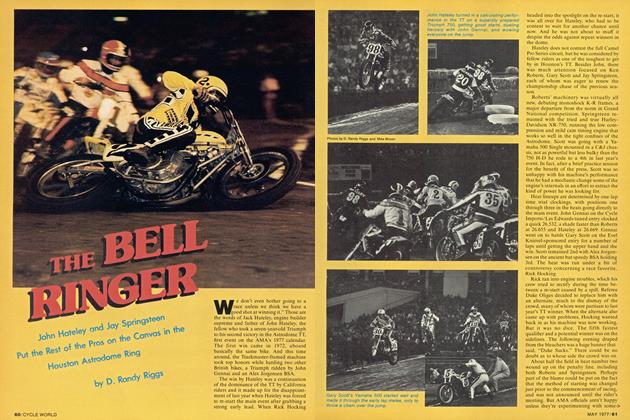

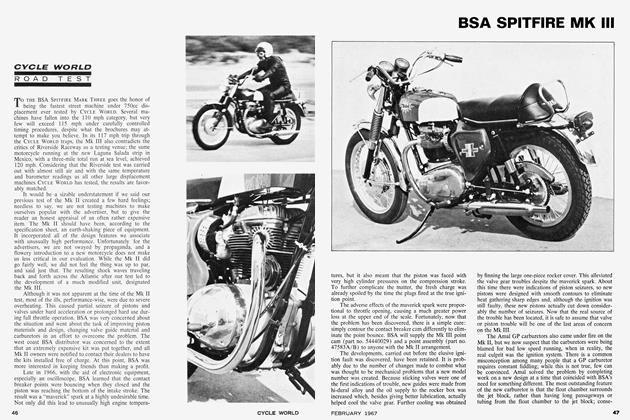

HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLCR-1000

The Beast that Keeps Milwaukee Famous

A crusty gentleman of legend late in his life was awarded one of his country’s highest honors, bestowed because his sovereign felt like it, rather than for any accomplishments. This pleased the recipient.

“None of this damned merit,” he chortled.

Were we rulers of all we survey, we'd do the same for Harley-Davidson’s XLCR1000. Merit be damned. The XLCR deserves some sort of prize, complete with banquet, not for what it does, but because it is.

That the CR exists is surprising. The official H-D history says that William G. Davidson, member of the founding family, head of Harley’s styling department and genuine bike nut, built the CR as something of a personal project, a motorcycle for his own use, to his own taste. Turned out the public flipped out and lo. the CR is now' an official low-volume semi-custom cafe racer, for sale at most dealerships if you hurry.

Perhaps. Harley-Davidson is a division of American Machine and Foundry. While we appreciate the benefits of corporations, the giant conglomerate is seldom a sentimental favorite. It pleases the emotions to think of Willie G, as he’s known at the plant, building a bike of his very own. We’d all have fun stripping a Sportster, plucking a 1000-cc engine ofl’the assembly line, persuading the brake and wheel and suspension suppliers to whip out a few special bits, dropping in on the racing shop and making off with the back half of an XR-750, visiting the boys in the fiberglass shop to ask for a rakish front fender, a pointy rear fender like the XR-750 has, a sharp little quarter fairing with, maybe, a smoked glass wind screen. For this you get paid?

No, you don’t. Corporations don’t succeed by letting their creative people indulge their every whim. What big (and small) companies do is, they let their creative people indulge any whim which promises to pay off in sales, prestige, profit, or all three.

What the XLCR is, then, is a special version of the Sportster, designed by a man who truly likes motorcycles, built in numbers low' enough to be exclusive and high enough to make the investment worth while. The CR was displayed to the public, which reacted just as you’d think, that is, there are guys clamoring to buy one for their very own. We see here the good side of having money influence design. One man’s custom usually fits one man. One man’s design modified by the need to please selected clients and meet various laws and rules is generally the better for the imposed limitations.

In terms of actual mechanical components, the CR begins with the 1977 Sportster. The CR uses the front—right, the front—of the Sportster frame. The rear subsection and most of the suspension parts are derived or copied from the production XR-750 professional racing model.

Mind, this isn’t a bolt-together operation. The CR frame is one unit, with the front section like a normal Sportster and the rear constructed of tubing designed to meet and match the upright rear shocks and the boxed XR-style swing arm.

Inside the frame goes the standard down-home Sportster engine, all 997.5 cc of it. Horsepower has been boosted with judicious tailoring of the spark advance curve and with a Siamese exhaust system; the two pipes join briefly and then go their separate ways, one for each side of the frame. The pipes are finished in matt black temperature-resistant paint. The first CR used black chrome, then the designers experimented with porcelain finish before deciding that either way was too expensive. So they settled for the paint, which looks businesslike and can also be re-done by the owmer at home if the need arises.

All the overall gears are lower than those of the stock Sportster, due to dropping one tooth at the primary drive.

The gearshift also required some work. Because the CR has its footpegs set well back on the frame, the shaft to the shifting mechanism emerges from the side case far too far forward. So the Harley engineers reversed the actual sequence inside the case, then flopped the lever, which now runs back toward the peg. The sequence is of course the mandated one; down for first, up for the rest.

Cycle World Road Test

The rear shocks, by look and lab test, seem to be those used on the regular model. They are moved back on the swing arm and mount upright, so the change in leverage gives the feeling of a stiffer spring. This also reduces wheel travel, of which the CR has little to spare.

Front forks are also Sportster, unchanged. The brakes are from KelseyHayes, dual discs in front and one disc in back and have not appeared on any previous Flarley. Wheels are Morris, cast alloy. They look good and surely add strength as well as cafe style.

Style—as well as styling—comes first from the fiberglass front fender. Then we move to the fairing which, except for the headlight, must have been directly done from a road-race fairing. The rear body section and fender are fiberglass, in one piece. The fender shape is inspired by the road-race XR-750. which is to say it looks like a normal fender uncurled from the wheel and stretched straight back by the force of supersonic winds. Zoom. Atop the fender and center section is one of the smaller motorcycle seats, actually a molded length of high-density foam covered by a Naugahyde pad held to the fiberglass with snaps.

The handlebars are replica clip-ons, actually a short length of chromed tubing with two bends and the standard Harley grips and controls at the ends. The controls are also standard H-D, cleverly simple, as in the light throttle return spring and the push buttons at left and right for the turn signals, which cannot be left on by mistake as your thumb gets tired.

A completely unexpected bonus is the fuel tank, which at 4 gal. capacity is nearly twice the size of the 1977 Sportster, at 2.2 gal. Presumably the road-racer look allows for a larger tank than the chopper look or whatever look they were after when they fitted the peanut tank.

In total, more good news. Something about the Harley-Davidson image of giant mechanical pieces gives the impression of weight. Fact is, at 515 lb. the CR is lighter than many more sophisticated multis and is only 7 lb. heavier than the stock Sportster. Our weights are taken with half a tank of fuel, so you can figure that 6 lb. of this is the extra gallon, meaning the fiberglass bodywork makes up for the added muffler and front disc. Nicely planned, anyway.

SUSPENSION DYNO TEST

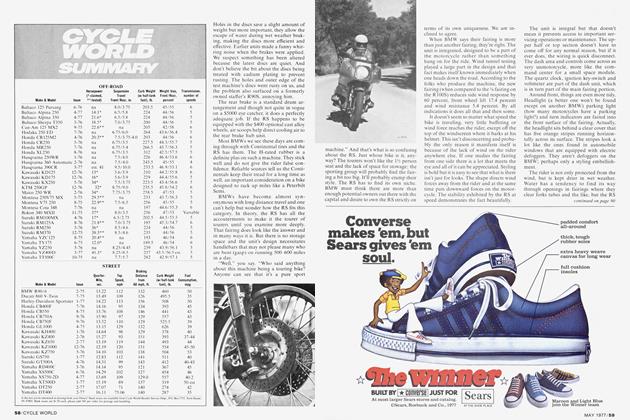

FRONT FORKS

Description: Showa fork, HD315 oil Fork travel, in.: 7.0 Engagement, in.: 6.0 Spring rate, lb./in.: 47 Compression damping force, lb.: 12 Rebound damping force, lb.: 47 Static seal friction, lb.: 20

Remarks: These are the same forks as used on the Sportster, and feel like it. The 47 lb. spring is far too stiff—a progressive spring with an initial rate around 30 lbs. should work well. Damping is okay, but high seal friction reduces suspension compliance somewhat. A switch to better seals should cure that.

REAR SHOCKS

Description: Gabriel shock, gas/oil mix, non-rebuikiable. Shock travel, in.: 2.2 Wheel travel, in.: 2.3 Spring rate, lb./in.: 100 Compression damping force, lb.: 22 Rebound damping force, lb.: 116

Remarks: Again, the rear shock is the Sporster unit, but the stiff Sportster ride is magnified by the nearly vertical shock angle. A softer spring might help, but the short shock stroke would allow the bike to bottom out too easily. An accessory shock with progressive springing is a must here.

Tests performed at Number One Products

Performance is at least as good as the image. The lower gearing and extra power more than compensate for the weight, so at 13.08 sec. for the standing quarter-mile the CR falls right into the middle of the superbike pack. The factory chaps were a bit miffed at our results. They took the bike to a different strip in the dawn’s misty light and ran a best E.T. of 12.79 sec. Use those figures, they suggested. We declined, as the only fair comparison comes from running all test bikes at the same place with the same riders and the same time of day. Even so, it’s fair to note that the CR is under some circumstances quicker than this test proves.

Brake performance was, well, poor. At low speed, the CR stopped in average distance, but from 60 mph, the CR used up more room than any comparable large road machine in recent memory, more distance even than the stock Sportster, despite the extra front disc and the rear disc.

The dual front brakes are the culprit. The braking pads are made of hard material. Harley-Davidson tech people say thev tried softer pads and got quicker stopping with less effort but they feared the rate of wear would be higher than the buyer expected. So they picked pads which will last a long time.

Adding to that, the hard pads require extreme muscular effort. Speaking fancifully, anybody with the strength to squeeze the front brake into locking the wheel doesn’t need brakes at all; if a locomotive looms, he’ll backhand it out of the way.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON

XLCR-1000

$3595

Miles-per-gallon was a pleasant surprise; not quite as good as the stock Sportster, but as good as other big bikes. Strange, that this old pushrod engine working against those huge gears and all can do as well as a modern dohc powerplant, but it does.

Note: The test CR came with 49-state mufflers. The tests show the CR with the mufflers for every place else to be three decibels louder than California permits road bikes to be. Harley has quiet mufflers in the works, for California buyers. They offered a set for the test. We declined. Worth saying, though, that the quiet mufflers likely will add a few tenths to the quarter-mile time and subtract a mile or so from the miles per gallon.

Enough figures. Riding the CR is, first off, different. In several ways.

If you’ve ever wondered what life would be like if you were 50 lb. lighter and 6 in. shorter than you are, no matter how heavy or tall you are, the CR will show you. The brake requirements have been mentioned. The clutch is the same, that is, an hour or so in traffic put one of our guys into the family car for a day. His left hand could take no more.

The gearshift lever is barely within reach of a size 9 or 10 boot tip and while the actual shifting is positive and cleanly performed, the leverage demand is such that one early learns to lift the boot off the peg, shove forward, hook the lever and haul smartly up with ankle locked and the main leg muscle doing the work. For downshifts, one picks up boot, moves forward and kicks down, hard.

The hand controls, i.e. turn signals, starter button—oh, yeah, the CR has full electrics. No point in carrying this racer replica theme too far—the hand controls, then are not . . . quite . . . convenient. Nobody in the office could manage to reach the turn button with his thumb while the rest of the hand was still doing useful things like controlling the throttle.

Counter to the above, perhaps, is comfort. Relative comfort. Swing aboard the CR and drop into the Cafe Crouch and it works better than one would expect. The bars are bent almost perfectly, in our collective case anyway, and setting feet ’way back in the chassis fits well with the posture of lying forward, leaning on the short bars and peering at the world over the smoked screen.

Posture. The road racing position puts the more padded parts of the human body right smack on the padded part of the motorcycle. When you sit bolt upright or slightly leaned forward, the bike seat usually gets you aft of the padded part, w here the gluteus maximus gives way to the bony bits. So. We motorcycle reviewers are forever complaining about the bikes not having enough seat padding. Turns out the Harley CR, with scarcely any padding at all. is comfortable for long rides, evidently because the posture puts the body weight where the body is designed to have it.

Add this to the clip-on style bars fitting the human wrist better than the styled bars of the normal Sportster. Then add having more fuel capacity and thus an extended cruising range, and you have a cafe racer version which is more comfortable and practical than the touring version it’s based on. Surely this is a first.

Reporting on actual operation of the transmission is a bit difficult, as a Harley-/ Davidson transmission is a device through which one gets into top gear at the earliest possible moment. None of this business of flicking through the gears. Haul on the hand and foot levers and keep the power on and hit fourth gear and that's all. The H-D engine has so much low end power that all the CR needs is first for starting and lunging through traffic and fourth for everything else.

Handling falls somewhere between what scoffers say about Harleys and what the CR looks like. The ride is, of course, rough. Equally true, the CR is not nearly as clumsy at low' speeds as one would expect. It doesn’t fall over or into corners and the bike is, as mentioned, lighter than it appears. And it can be easily balanced for turning corners in the city and so forth.

Tracks well, on smooth pavement. Strike that. All the time. The CR has a relatively long wheelbase and there is no trouble keeping it going where pointed, provided the bike is pointed straight ahead.

Fast sweepers at a constant speed are where the CR works best, as it should. Set up for a line and keep the power steady and the CR will hold that line. It will not wish to change lines, though, even though the rider may. And at the extreme end of cornering power, with the pipes about to touch down and with the bumps in the road getting the best of those upright shocks and stiff springs, the rider has the feeling that the CR really is part of a Sportster attached to part of an XR-750, that is, as if Section A and Section B were working against each other at Slot C. The CR is surely fast and up to a point the CR is nimble, but there’s too much mass there for the CR to be a boy racer's delight.

Enough of this damned merit.

Figures and actual road behavior begger the point.

Harley-Davidson is a state of mind, a time freeze, a reference point all its own.

Harley-Davidson is an engine. The engine. That obsolete evergreen V-Twin, never quite right and always better than it should be, that great lovely lump of black iron and polished aluminum, those covers and crevices and bulging pipes.

Those noises. Not only the exhaust, which to those of us of a certain age shouts Motorcycle! from blocks away, but all the unearthy sounds.

Out of the V-Twin come rumbles and rattles enough to send the Wabash Cannonball whimpering home to the roundhouse. There are gears howling and chains flailing and who-knows-what banging and shaking. Standing next to an idling Harley is like living in the engine room of a tramp steamer.

And yet. like your grandfather’s coal furnace with its groans and shudders, every time you need it, the Harley Twin carries on. The Men in Milwaukee have been building this strange pushrod survivor for generations and if they don’t keep it quiet, they do make it work. Nothing in the Survival-Of-The-Fittest Handbook says the path to progress is traveled only on tiptoe.

Now. What you do on the CR is climb aboard this giant old engine, wrap your limbs around whatever falls to hand, foot and knee, and thunder away, as close to Joe Leonard or Jay Springsteen as we mortals will ever come.

As a motorcycle, the XLCR has not much merit.

As an adventure, the XLCR has no equal. g