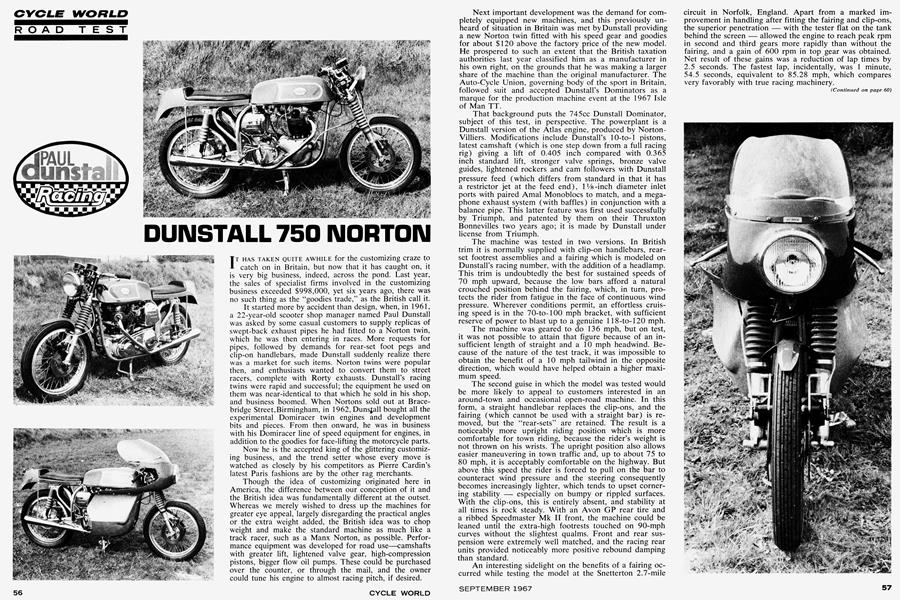

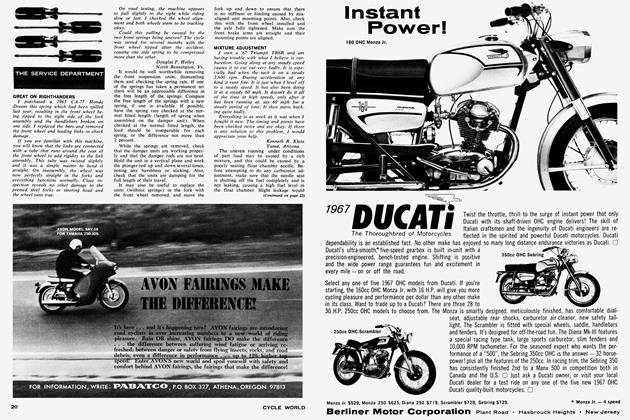

DUNSTALL 750 NORTON

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

IT HAS TAKEN QUITE AWHILE for the customizing craze to

catch on in Britain, but now that it has caught on, it is very big business, indeed, across the pond. Last year, the sales of specialist firms involved in the customizing business exceeded $998,000, yet six years ago, there was no such thing as the "goodies trade," as the British call it.

It started more by accident than design, when, in 1961, a 22-year-old scooter shop manager named Paul Dunstall was asked by some casual customers to supply replicas of swept-back exhaust pipes he had fitted to a Norton twin, which he was then entering in races. More requests for pipes, followed by demands for rear-set foot pegs and clip-on handlebars, made Dunstall suddenly realize there was a market for such items. Norton twins were popular then, and enthusiasts wanted to convert them to street racers, complete with Rorty exhausts. Dunstall's racing twins were rapid and successful; the equipment he used on them was near-identical to that which he sold in his shop, and business boomed. When Nortons sold out at Bracebridge Street, Birmingham, in 1962, Dunsjall bought all the experimental Domiracer twin engines and development bits and pieces. From then onward, he was in business with his Domiracer line of speed equipment for engines, in addition to the goodies for face-lifting the motorcycle parts.

Now he is the accepted king of the glittering customizing business, and the trend setter whose every move is watched as closely by his competitors as Pierre Cardin's latest Paris fashions are by the other rag merchants.

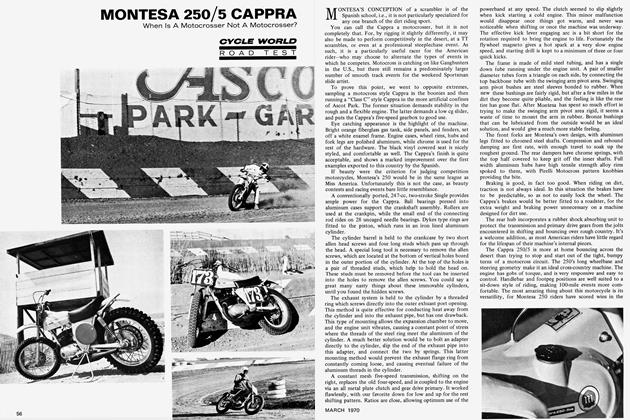

Though the idea of customizing originated here in America, the difference between our conception of it and the British idea was fundamentally different at the outset. Whereas we merely wished to dress up the machines for greater eye appeal, largely disregarding the practical angles or the extra weight added, the British idea was to chop weight and make the standard machine as much like a track racer, such as a Manx Norton, as possible. Performance equipment was developed for road use—camshafts with greater lift, lightened valve gear, high-compression pistons, bigger flow oil pumps. These could be purchased over the counter, or through the mail, and the owner could tune his engine to almost racing pitch, if desired.

Next important development was the demand for completely equipped new machines, and this previously unheard of situation in Britain was met byDunstall providing a new Norton twin fitted with his speed gear and goodies for about $120 above the factory price of the new model. He prospered to such an extent that the British taxation authorities last year classified him as a manufacturer in his own right, on the grounds that he was making a larger share of the machine than the original manufacturer. The Auto-Cycle Union, governing body of the sport in Britain, followed suit and accepted Dunstall's Dominators as a marque for the production machine event at the 1967 Isle of Man TT.

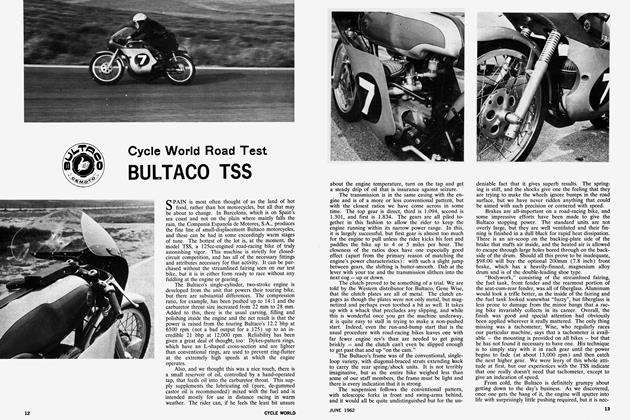

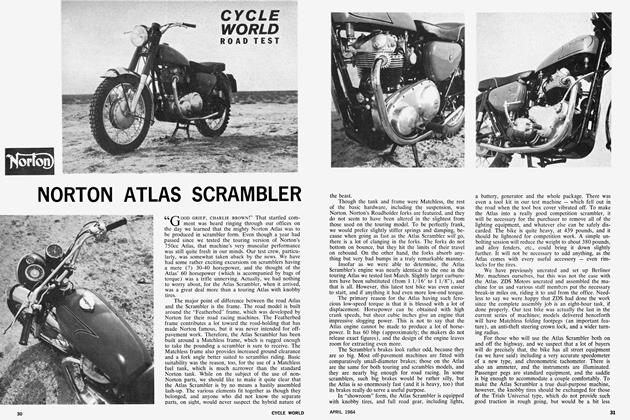

That background puts the 745cc Dunstall Dominator, subject of this test, in perspective. The powerplant is a Dunstall version of the Atlas engine, produced by NortonVilliers. Modifications include Dunstall's 10-to-l pistons, latest camshaft (which is one step down from a full racing rig) giving a lift of 0.405 inch compared with 0.365 inch standard lift, stronger valve springs, bronze valve guides, lightened rockers and cam followers with Dunstall pressure feed (which differs from standard in that it has a restrictor jet at the feed end), lVs-inch diameter inlet ports with paired Amal Monoblocs to match, and a megaphone exhaust system (with baffles) in conjunction with a balance pipe. This latter feature was first used successfully by Triumph, and patented by them on their Thruxton Bonnevilles two years ago; it is made by Dunstall under license from Triumph.

The machine was tested in two versions. In British trim it is normally supplied with clip-on handlebars, rearset footrest assemblies and a fairing which is modeled on Dunstall's racing number, with the addition of a headlamp. This trim is undoubtedly the best for sustained speeds of 70 mph upward, because the low bars afford a natural crouched position behind the fairing, which, in turn, protects the rider from fatigue in the face of continuous wind pressure. Wherever conditions permit, an effortless cruising speed is in the 70-to-100 mph bracket, with sufficient reserve of power to blast up to a genuine 118-to-120 mph.

The machine was geared to do 136 mph, but on test, it was not possible to attain that figure because of an insufficient length of straight and a 10 mph headwind. Because of the nature of the test track, it was impossible to obtain the benefit of a 10 mph tailwind in the opposite direction, which would have helped obtain a higher maximum speed.

The second guise in which the model was tested would be more likely to appeal to customers interested in an around-town and occasional open-road machine. In this form, a straight handlebar replaces the clip-ons, and the fairing (which cannot be used with a straight bar) is removed, but the "rear-sets" are retained. The result is a noticeably more upright riding position which is more comfortable for town riding, because the rider's weight is not thrown on his wrists. The upright position also allows easier maneuvering in town traffic and, up to about 75 to 80 mph, it is acceptably comfortable on the highway. But above this speed the rider is forced to pull on the bar to counteract wind pressure and the steering consequently becomes increasingly lighter, which tends to upset cornering stability — especially on bumpy or rippled surfaces. With the clip-ons, this is entirely absent, and stability at all times is rock steady. With an Avon GP rear tire and a ribbed Speedmaster Mk II front, the machine could be leaned until the extra-high footrests touched on 90-mph curves without the slightest qualms. Front and rear suspension were extremely well matched, and the racing rear units provided noticeably more positive rebound damping than standard.

An interesting sidelight on the benefits of a fairing occurred while testing the model at the Snetterton 2.7-mile circuit in Norfolk, England. Apart from a marked improvement in handling after fitting the fairing and clip-ons, the superior penetration — with the tester flat on the tank behind the screen — allowed the engine to reach peak rpm in second and third gears more rapidly than without the fairing, and a gain of 600 rpm in top gear was obtained. Net result of these gains was a reduction of lap times by 2.5 seconds. The fastest lap, incidentally, was 1 minute, 54.5 seconds, equivalent to 85.28 mph, which compares very favorably with true racing machinery.

(Continued on page 60)

In terms of sheer acceleration, the Dominator is quicker up to 100 mph than, say, a 499cc Manx Norton or 496cc G50 Matchless, in spite of being approximately 95 pounds heavier. Drill for taking the standing-start performance figures was to rev the motor to 6,000 rpm, then drop the clutch smartly and spin off the mark for about 25 feet before the tire bit again. Drastic though the treatment may sound, it saved abusing the clutch on a high bottom gear and consistently returned times under 13 seconds, with a terminal speed of over 100 mph. (A standard unfaired Atlas has a maximum of around 115 mph, turns the quarter in 15 seconds, with a terminal speed of 92 mph).

Although the new Amal concentric-bowl carburetors are now being fitted to many British production mounts, Dunstall has so far failed to obtain as good results with them as with the superseded Monoblocs. For some reason, an Atlas fitted with concentrics lacks bottom-end power, and this has been reflected in relatively inferior standingstart acceleration figures on previous tests. Until the concentric proves superior, Dunstall is sticking to Monoblocs.

A claimed benefit of the exhaust balance pipe is a power boost in the middle rpm range because of the effect the balance pipe exerts on the exhaust resonance.

The megaphone-pattern silencers are patented and designed to provide an extractor effect for the exhaust gases. Up to about 3,500 rpm, the level of exhaust noise is acceptably low and torque is such that these revs need never be exceeded in towns or built-up areas — 3,500 in top is equivalent to 68 mph. From 4,000 upward, the exhaust note becomes louder, but the distinctive feature is that the note is deep-throated, and because it does not have the sharp, high-pitched note of a small-capacity four-stroke or two-stroke, it is not obtrusive or offensive.

A characteristic feature of Dunstall's engines is their smoothness. This is no accident, but comes from careful assembly and preparation. In standard form, the Atlas has never been the smoothest of units and sharpening it for higher performance might have aggravated the roughness, but this has proved unfounded. It is without any noticeable vibration period, and at peak rpm, is smoother than most production big twins at half that engine speed.

Standard Norton brakes are among the most powerful in production, but this is not to say they cannot be improved. A radical, and unique, departure are the Lyster twin-disc hydraulically operated brakes which Dunstall now offers as part of his conversion service. Tested under racing conditions — surely the stiffest test — the discs proved extremely powerful fade-free stopping. Operation is light and positive, without any lost motion in the linkage to the hydraulic master cylinder, and it is sufficiently sensitive to allow delicate and easily controllable braking on tricky surfaces, such as wet or greasy streets. When making a series of maximum-effort stops from 120 mph, the front tire could be made to squeal from that speed right down to zero without actually locking the wheel. Stopping from 125 mph to standstill took 215 yards. Only snag with discs is the problem of rust in wet or damp weather, but the disc discoloration clears on the friction surface after the brake has been used. Experiments are in hand to find a permanent cure.

Bright red fiberglass is used for the fairing, fuel tank and seat unit. The fairing has detachable side panels, finished in metallic gray, for access to the engine; the matching speedometer and rev counter, with an ammeter and light switch, are mounted in a raised facia in the nose of the fairing. Finish of the fiberglass work and chromeplated parts is of a high quality. Although the Dominator is intended as a super-sporting roadster, provision is made for carrying a passenger in reasonable comfort on short runs. With a small gas tank holding 3 Vi gallons, range is no more than 140 miles between refilling.

For those accustomed to push-button starters, a few shocks are in store; the Atlas engine was never intended for striplings. It starts on the second or third swing from cold, after liberal flooding of both carburetors (cold starting chokes are not fitted) and with the throttles set slightly open; but a really beefy effort is needed with a good follow-through on the crank. A throttle setting of one-third open is required when the engine is warm.

That, then, is the Dunstall Dominator — a specialist mount for those who want more suds than any other current production machine can offer. Dunstall makes no proud claims, but he could justifiably say it is the fastest machine generally available anywhere in the world today.

DUNSTALL

750 NORTON

$1,340