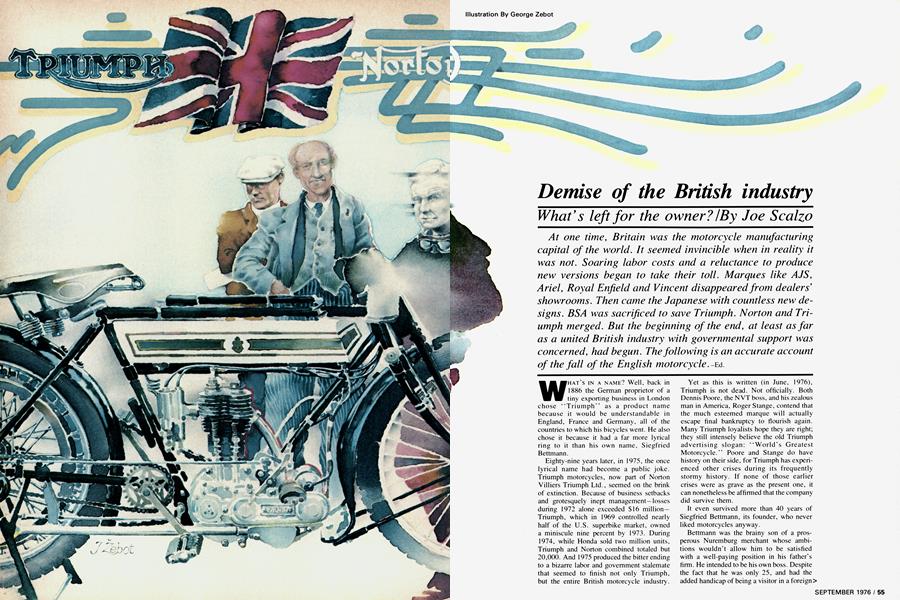

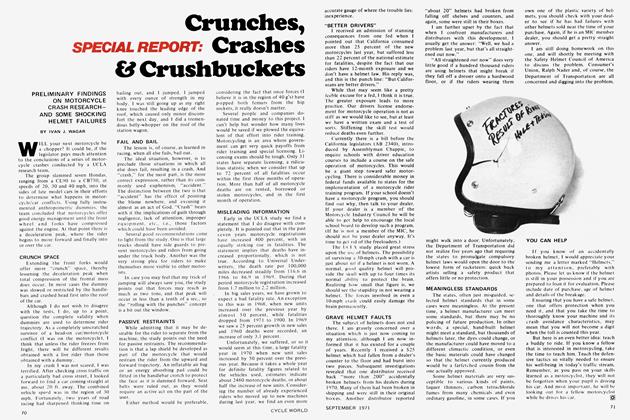

Demise of the British industry

What's left for the owner?

Joe Scaizo

At one time, Britain was the motorcycle manufacturing capital of the world. It seemed invincible when in reality it was not. Soaring labor costs and a reluctance to produce new versions began to take their toll. Marques like AJS, Ariel, Royal Enfield and Vincent disappeared from dealers’ showrooms. Then came the Japanese with countless new designs. BSA was sacrificed to save Triumph. Norton and Triumph merged. But the beginning of the end, at least as far as a united British industry with governmental support was concerned, had begun. The following is an accurate account of the fall of the English motor cycle. -Ed.

WHAT’S IN A NAME? Well, back in 1886 the German proprietor of a tiny exporting business in London chose “Triumph" as a product name because it would be understandable in England, France and Germany, all of the countries to which his bicycles went. He also chose it because it had a far more lyrical ring to it than his own name, Siegfried Bettmann.

Eighty-nine years later, in 1975, the once lyrical name had become a public joke. Triumph motorcycles, now part of Norton Villiers Triumph Ltd., seemed on the brink of extinction. Because of business setbacks and grotesquely inept management—losses during 1972 alone exceeded $16 million— Triumph, which in 1969 controlled nearly half of the U.S. superbike market, owned a miniscule nine percent by 1973. During 1974, while Honda sold two million units, Triumph and Norton combined totaled but 20,000. And 1975 produced the bitter ending to a bizarre labor and government stalemate that seemed to finish not only Triumph, but the entire British motorcycle industry.

Yet as this is written (in June, 1976), Triumph is not dead. Not officially. Both Dennis Poore, the N VT boss, and his zealous man in America, Roger Stange, contend that the much esteemed marque will actually escape final bankruptcy to flourish again. Many Triumph loyalists hope they are right; they still intensely believe the old Triumph advertising slogan: “World's Greatest Motorcycle.’’ Poore and Stange do have history on their side, for Triumph has experienced other crises during its frequently stormy history. If none of those earlier crises were as grave as the present one, it can nonetheless be affirmed that the company did survive them.

It even survived more than 40 years of Siegfried Bettmann, its founder, who never liked motorcycles anyway.

Bettmann was the brainy son of a prosperous Nuremburg merchant whose ambitions wouldn’t allow him to be satisfied with a well-paying position in his father’s firm. He intended to be his own boss. Despite the fact that he was only 25, and had the added handicap of being a visitor in a foreign country, Bettmann achieved his goal when he founded the Triumph Cycle Co. It took the company barely two years to outgrow its London headquarters.

With the assistance of a junior partner— another young German named Mauritz Schulte—Bettmann began selling Triumph “directorships” to investors. Large and small contributors were encouraged. Finally the merchant’s son had sufficient money to move the growing business quarters to Coventry in the industrial midlands.

Raising funds this way pleased Bettmann so much that he seems to have reused the method frequently; in 1907, for instance, Dunlop came in with an investment of nearly £45,000 in a deal that made Bettmann and Schulte joint managers and resulted in Triumph’s third move to larger quarters.

But Schulte apparently objected to his countryman’s selling so many directorships and said so. There was to be more and more dissension between the two as the years wore on. In their authorized biography The Story of Triumph Motorcycles, Harry Louis and Bob Currie give Bettmann most of the credit for holding Triumph together, noting that he was the business brain and Schulte merely the chief engineer and designer.

Not, in those early days, that that much “designing” occurred. Bicycles, not motorcycles, continued to be the staples of the newly incorporated Triumph Cycle Co. Ltd. Though the first motorized tricycle had appeared in England as early as 1884, it was years before motor-driven cycles were taken seriously at Triumph. Finally, after some tentative attempts, the first motorized Triumph appeared in 1902: a Belgian Minerva engine of one horsepower clipped to the front of a bicycle frame, complete with pedals.

By 1903 Triumph was producing 500 such units a year, but was still so uncertain about them that it continued using other people's parts. The 1904 Triumph, for example, borrowed a J.A. Preswich pump engine.

Schulte produced the first Triumph engine in 1905, and it was considered unremarkable, but in following years the engineer couldn't decide between twoand four-stroke power. Even deciding where to mount the engine in the frame was a problem. Little serious consideration was given to the suspension, meaning that year to year, as new components were tried, a Triumph might alternately have too soft a suspension ... or none at all. Gradually and perhaps grudgingly, features such as gearboxes, clutches, kickstarters, and magneto ignitions found their way onto Triumphs. Production increased until, by 1909, 3000 Triumphs were being produced yearly. Although still unremarkable mechanically, Triumphs were famous for their reliability and fine workmanship. And this tradition continued for decades, until the big collapse in the ’70s.

Schulte's conservatism may have been what kept Triumph afloat financially. The motorcycle, a still new and not fully accepted toy, was fighting for acceptance. Competition was keen, with as many as 100 factories slugging it out for sales. Most were tiny and underfinanced and disappeared quickly, but Schulte's biographers credit him with creating “the first truly reliable motorcycle to be put on sale.” He wasn’t blind to progress, however, and as early as 1913 was thinking about a vertical twin-cylinder engine. Still cautious and conservative, he eventually rejected it because he couldn’t find a way to beat the vibration.

Yet for all Schulte’s work and Bettmann’s ambition, their company was never more than modestly profitable, although the fact that it survived those difficult early years is itself a tribute. But Bettmann didn’t like motorcycles. He chose to believe that the biggest profits could still be made from bicycles.

A fantastically self-assured person who thought he could do no wrong (in 1907, angry about financial losses, Triumph investors were ready to make Bettmann walk the plank, but found him an unwilling scapegoat; during a stockholders meeting the German took to the podium and argued heatedly with his dissenters, justifying his position), Bettmann became a Coventry councilman in 1907 and, incredibly enough, city mayor in 1914. This at a time when his homeland and England were going to war. Not only that, but throughout World War I and until 1929, Bettmann operated a second bicycle-producing plant deep inside Germany.

World War I, more than anything else, established the motorcycle’s viability. It certainly established Triumph. Armies on both sides needed motorcycles for dispatch riders, and 30,000 Model H 500cc Triumphs were supplied to Britain and her allies during the war years.

But the evidence seemed to leave Bettmann unmoved: following the war, with the European economy in ruins, he argued for slowing motorcycle production and accelerating the company’s less-expensive bicycle line. Others at Triumph leaned toward the automobile, and Bettmann, perhaps surprisingly, heeded their advice. In 1923 Triumph began manufacturing cars beginning with a little puddle-jumper good for 47 mph flat out.

Mauritz Schulte was no longer there to see it. After putting 32 years of his life into Triumph, and designing “the first truly reliable motorcycle,” his share of the company was bought out by Bettmann, with whom he was no longer on speaking terms. The sizable sum he took away from Triumph did not appear to please Schulte, who died two years later.

With Schulte gone, Triumph motorcycles ceased being conservative. New designers had begun tooling up for high-performance models. Ricardo & Co. produced a splendid four-valve cylinder head engine and called it the Triumph R; riders who raced them on the Isle of Man complained that the added horsepower had outpaced frame development. The year 1920 saw the first all-chain transmission, 1922 dry-sump lubrication, 1923 a unit-construction 350cc Model LS; and in 1925 a mass-produced and inexpensive Model P came into being.

Even at reduced prices, none of these Triumphs sold very well. England was suffering from devastating inflation, crippling labor strikes and, in 1926, the massive General Strike. Other companies were going out of business while Triumph struggled to simultaneously turn out motorcycles, bicycles and cars. The bicycle end of the business—to what must have been Bettmann’s chagrin—was sold off in 1932. Yet the following year a remarkable Triumph 650cc vertical Twin called the Model 5 Sportster appeared.

Designed by the Englishman Val Page, the Model 5 was big, bold, and impressed everyone but the Triumph management. Their reaction was to palm it off to Alfa Romeo in exchange for the rights to the Italians’ eight-cylinder MK 8C car engine. The engine would be used to power an elegant Triumph automobile called the Gloria Dolomite.

Only three such cars were actually built, but the staggering expense helped to send Triumph careening toward bankruptcy. Siegfried Bettmann, now in his dotage, was apparently judged responsible for the disaster and demoted from managing director to vice-chairman. Times were clearly changing. To Lloyds’ bank, which temporarily owned Triumph, it seemed that the day of the motorcycle had ended; car production had clearly to be accelerated. The motorcycle division of Triumph was to be sold.

For £50,000 it passed, in 1936, into the hands of a dedicated motorcycle believer named Jack Y. Sangster. An astute businessman who had already achieved success in the automobile business, Sangster was the son of the owner of the Ariel Company, which had ceased car production to build motorcycles. Enthusiastically, Sangster declared that the newly financed Triumph Engineering Corp. would “Be controlled and managed by men who are motorcycle specialists.”

In spite of that, Sangster's first move was to invite old Bettmann, who was less than a “motorcycle specialist," to serve as chairman. But Bettmann was quickly removed from that post and replaced by the strong-willed individual whose name to this day remains synonymous with Triumph: Edward Turner.

Turner was a short, pompous sort of man, and those who remember him best contend that he'd have made an excellent Prime Minister. He was outspoken and sure of his own and Triumph's place in the world. He, personally, coined the slogan “World’s Greatest Motorcycle.” Because he was so short and so conscious of effect, the little Englishman had props put beneath his office desk so that he could look down at all who came to see him.

As an engine designer, Turner was an acknowledged genius.

And it was all self-taught knowledge. As a 14-year-old ship's radio operator in the Navy, Turner had studied and mastered engineering in his spare time. During the ’20s he built a 350cc overhead cam engine of his own. Later, working at Ariel, he designed one of the fabled motorcycles of all time: the Ariel Square Four.

But like most creative people, Turner was at times irascible. Currie and Louis describe him charitably as, “not being the easiest man to work with.” As Triumph's managing director Turner insisted that things be run his way or no way at all. Jack Sangster backed him up by giving Turner, his pet since his years at Ariel, absolute authority. Later, during World War II, a quarrel caused Turner to quit Sangster and Triumph; two years later, however, Sangster invited Edward back to Triumph and gave him more authority than ever.

Turner’s dictatorial methods had been revealed in 1936, his first year at Triumph. Deciding that wages at the Coventry plant were too high, he gave assembly line workers the option of working for less or being laid off. Although today’s heavily unionized English workers would find this impossible to credit, the Triumph assemblers agreed to stay on.

Turner also completely rebuilt Triumph’s sales and marketing organizations, despite the fact that he had little experience in such fields. His penny-pinching was notorious, although perhaps justified by the hard economic times in which he lived. If, for instance, he felt he could sell, say, 3000 units, he would hedge and produce only 2500, thereby assuring Triumph at least that many sales. (Years later, in 1975, a consulting team of accountants would criticize Triumph’s exclusive concern for “short term” profits, a holdover from the earliest Turner days).

In spite of all the other claims on his time, Turner didn’t neglect his engineering duties, for he was Triumph’s chief engineer too. What made him a legend at Triumph, and established his continuing reputation as a genius, was his 1937 break-through engine, the 500T Speed Twin. Years ahead of its time, it was regarded as the inspiration for all future parallel Twins. He had designed it, Turner said, because “it gives better torque, runs at higher revolutions than a single-cylinder and with less strain to its components, is faster accelerating, more durable, and easier to silence and cool.” A hot engine, the Speed Twin could hit 90 mph on the measured mile; with it, Triumph was able to challenge Norton, the other British cycle company, in the highperformance field. But Triumph, unlike Norton, disavowed racing as a factory policy. “Let Norton lose its bloody shirt racing,” Edward Turner sniffed. He added: “Today’s racing machines are special from wheel to wheel, and there is nothing that can be translated into production.”

Turner was saying that racing could not be used as a testing laboratory and he was right. But, because his mind didn't run that way, he neglected to consider the public relations and advertising value of racing. He never changed his policy, nor did Triumph's American exporters until 1970, when they spent $400,000 racing in one spectacular season. But by then, as it turned out, it was already too late to do them any good.

Despite an occasional error, it appears that Turner did a reasonably good job of holding the struggling Triumph Corp. together in the days immediately preceding the second world war. Although everyone knew that war was coming, and that the army would be calling upon Triumph for motorcycles again, Triumph was caught flat-footed and had no such machines available. Turner had just lost his wife in a tragic highway accident and was perhaps preoccupied with his grief. In any case, on November 14, 1940, Triumph was still gearing up for wartime production when squads of Luftwaffe bombers plastered the plant and much of Coventry.

Although not a single Triumph workman was killed, the headquarters was reduced to a crumpled, smoking skeleton.

Turner and his boss Jack Sangster were for rebuilding the facility immediately. But the War Damage Commission refused to grant permission. The old Triumph headquarters was too close to downtown Coventry and might attract further bombing raids. Triumph should instead rebuild four miles away, in a less populated area near the main Coventry-Birmingham road. Three decades later, the village in which the new plant was eventually erected would be the site of a different type of battle. Its name was Meriden.

Four-stroke racing revivali

Joe Scaizo

With the British decline, interest in four-strokes for sportsman racing diminished, even in the big-bore classes. And why not? There were no new concepts to offset the onslaught of European and Japanese two-strokes that offered lighter weight, more power and easier maintenance. Then a funny thing happened. First Honda, then Yamaha, began producing four-stroke Singles for the dirt. Before long, some found their way to the race track, leading to a revival, of sorts, of four-stroke-only racing. This type of racing provides an outlet for purchasers of Japanese machines and British owners alike.-Ed.

jMT CARLSBAD, CALIF., this Sept. 19, the pipey shriek of two-strokes, the sound that more than any other is associated with motocross in the ’70s, will be blissfully absent. Nostalgic ears will instead be attuned to the husky basso profundo of older but still willing BSAs, Ariels, Nortons and, of course, Triumphs. The U.S. Four-Stroke National Championships will have begun.

Riding the backs of these awe-inspiring four-strokes (this type of competition is known in some areas as dinosaur racing), will be famous names from motorcycling's past, individuals who once made their reputations on such warhorses: Feets Minert, Preston Petty, C.H. Wheat, the great Englishman Jeff Smith and his former World Championship rival, Rolf Tibblin.

These are the men from the old days who haven’t raced seriously in years. And yet nostalgia and the lure of this one race are enough to temporarily draw them back.

The idea man behind the race is the owner of the Knobby Shop in LaJolla, Calif., Allen Greenwood. The Knobby Shop is a dirt bike emporium, and Greenwood is a dirt racing advocate and old bike buff. Missing more and more the once-familiar fourstroke thunder, he finally went ahead and organized the race last year with help from Larry Grimser of the Carlsbad track and friend Butch Lee. “We had over 100 entries,” he says enthusiastically. “This year we’re looking for double that.”

Last year there were old-timers who trucked their four-strokes in from as far as 111. and Mo. Classes are broken down thusly: 100-15lcc, 151-350cc, 350cc-Open. Prize money is $600, the AMA maximum for an event such as this. Spectator admission is $1.

It’s a day when the past can live again, however temporarily. And the crowd can hear the distinctive Triumph battle cry that, despite the best (or worst) efforts of so many people, refuses to die.

The war ended. While the British economy was smashed, the American economy seemed to be booming. Hard-hit Britons might be unable to afford Triumphs, but Americans could. With economic conditions pressing in, there was a market for smalldisplacement, inexpensive, basic-transportation motorcycles at home, but Triumph managed to ignore that fact.

And why not? Americans had money. And the only competition in the U.S. came from moss-backed Harley-Davidson and the foundering Indian Co.

Following the war, perhaps 12 motorcycle dealers in the U.S. sold Triumphs, none of them moving more than a handful per year. One of them was a Pasadena, Calif., attorney and Anglophile named Bill Johnson, a personal friend of Edward Turner. Johnson Motors in Pasadena soon became Triumph’s U.S. distributor and by 1950 was selling 1000 Thunderbird and Tiger sport models per year. Production back at Meriden had risen 15 percent over the previous year.

Encouraged by these figures, and by American sales prospects generally, Triumph set up its own East Coast branch in Maryland, while Johnson Motors retained control of the 19 western states. Uneasy with this foreign poaching on its previously private hunting grounds, Harley-Davidson hauled Triumph before the U.S. courts, asking, but failing to get, import tariffs on foreign-made motorcycles raised to 40 percent.

The opening of the Triumph Corp. in Baltimore was not, however, the most significant thing to occur in 1951.

The most significant thing had been Jack Sangster’s selling of Triumph to British Small Arms Ltd. (BSA) for £2.5 million.

BSA was, at that time, a giant conglomerate that owned, among other things, Daimler cars, buses and military vehicles, Hopper coachbuilders, Jessop special steels, BSA guns and bicycles, and Ariel, Sunbeam, New Hudson and BSA motorcycles.

Sangster's decision to sell the company he had owned for 15 years was based on his belief that he was going to die. Taxes were already a growing horror in England, and Sangster was advised that if he kept Triumph his heirs would be burdened with prohibitively high estate taxes. Sangster, fortunately, did not die (reportedly he is alive today, although in his 80s). Within five years of the sale he was back in action again, serving as director of BSA.

Under the terms of the sale, crotchety Edward Turner was able to exercise even more authority than he had previously. He was placed in charge of all BSA automobile and motorcycle divisions. One of his pet projects was designing a V-8 Daimler engine that was technologically interesting but a commercial failure.

Turner had other failures. His attempts to design inexpensive scooters were unsuccessful. Certain Triumph innovations he attempted—fully-enclosed body panels, the “Slickshift” gearchange, and, notoriously, the sprung-hub suspension design—were ill-received.

But Turner efforts like the TR5 and TR6 Trophy Triumphs, and, of course, the Bonneville, more than made up for such lapses. These Triumphs had something. They exuded that smugness that seems uniquely British. Their proponents extoll, to this day, their styling, top-class roadholding, steering, braking and low center of gravity.

One such advocate is Patrick (Pat) Owens, an instructor at Los Angeles Trade Tech College, and an owner of three Triumphs.

The Triumph Owens is proudest of is his 1963 TR6, raced to a championship in the Mojave desert by the legendary Eddie Mulder. Mulder later campaigned the bike in scrambles competitions —forerunners of today’s motocross. After all that racing Owens put headlights on it and in the past 10 years he and his wife have ridden the bike all across the country, 75,000 highway miles in all. It’s still running today, and with the same crankshaft. “No other motorcycle,” Owens says proudly, “ever was able to do so many things so well.” (See CYCLE WORLD, May ’66).

During the years between 1950 and 1969, Triumph’s American sales were the highest ever recorded by a British motorcycle company. Profit reports from this period have ranged from “great” to “modestly profitable,” but there is no doubt that Triumph made money.

Not that things were perfect. Far from it. The minor irritants of the ’50s and '60s that would become the calamities of the '70s were there to be seen by anyone inclined to look.

There was, for one thing, the friction that existed between Johnson Motors in the West and the Triumph Corp. in the East. It seemed to center around the West’s Pete Coleman, and the East’s Rod Coates (described by Pat Owens as the “most important” figure in the entire Triumph organization). The tension fused into a narrow personal rivalry that extended even to the race tracks, where Johnson Motors’ West Coast entry and Triumph Corp. ’s East Coast entry each pulled out all the stops to beat the other.

There were problems, too, in that no really new Triumphs were being introduced. The vertical Twin design was two or more decades old, but no serious attempts were made to upgrade it. Pete Coleman says that he and his Johnson Motors associates continually lobbied for new engine designs and new models, often flying to England to confront Edward Turner and his designers face to face. But it was all to no avail.

Although Triumph was willing to sell the vast majority of its motorcycles in the U.S., it did not seem willing to accept the advice of its American personnel.

Not only were the designs stale, but the Triumph factories themselves were antiques. So were the tools being used. Besides lacking the desire, Triumph simply did not have the means to mass-produce large numbers of motorcycles. “We never got all the Triumphs we wanted or could have sold,” Coleman recalls. “At times we might have sold 50,000, but felt lucky to get 20,000.”

Still, there was no serious competition from other marques in the U.S. marketplace— except for Harley-Davidson—so Triumph could enjoy a false security. But the arrival of the Japanese—of Honda—would change all that.

No one took Honda seriously at first.

Japanese motorcycle exports, prior to 1960, stood at only eight percent. Johnson Motors had even turned down the opportunity to become Honda’s U.S. sales arm.

Later, when Honda was finally on the verge of launching its American assault, Bill Johnson met socially with a Honda executive named Nokamura who was visiting from Japan.

Overdrinks, Bill Johnson asked his visitor how many motorcycles Honda believed it could sell at first.

“About 6000,“ was Mr. Nokamura’s polite reply.

Johnson smiled to himself. Johnson Motors sales at that time ran to roughly 3000 per year.

“That’s a pretty good sales figure for a year,’’ Johnson commented.

Blushing, Mr. Nokamura apologized for the apparent confusion. Not 6000 motorcycles a year, he explained. Six thousand a month.

The story is not apocryphal: Pete Coleman was a witness to it, just as he was a witness to Honda’s overpowering success in the years to follow.

Honda sales were achieved through a combination of skillful marketing and large advertising budgets. But Triumph still underestimated the Japanese. Triumph —and the rest of the British motorcycle industry—gave up without regret the small-displacement motorcycle market. Triumph had no 50, 125, 175, 250 or 350cc models anyway. The smug thinking that seemed to prevail at the time was that the production of bigger motorcycles was quite beyond Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki. This was prideful and wishful thinking. For with the Japanese achieving such success with small motorcycles, surely their big ones couldn't be far behind.

In a report highly critical of the British motorcycle industry that was issued in 1975, the Boston Consulting Group calls this the “fundamental mistake.”

The report contends that the British should have built and marketed small motorcycles of their own; they should have stood and fought the Japanese rather than retreating. Says the report: “Short term profitability would have suffered, but this approach would have meant a sound long-term future.”

Pete Coleman, who was swept out of the Triumph organization during one of the many management changes of the ’70s, said the report failed to take into consideration the mood at Triumph at that time.

“Could Cadillac have competed against Volkswagen?” he asks. “It’s not that easy. Expecting Triumph to be able to turn out as many units as Honda becomes ridiculous when you realize that in America we were ordering 50,000 units a year and felt lucky to get 20,000.”

Nor, Coleman believes, would the shareholders of Triumph’s parent company, BSA, have endorsed a policy of expansion and long-term investment. “They wanted their profits, meager as they were, to continue,” he says.

During the '60s, Triumph, its sales pushed only by the overall motorcycle boom created by the Japanese, continued making money. Yearly sales rose. But two principals were gone from the scene by then: Bill Johnson died in March, 1963 (Johnson Motors was purchased by the BSA group), and Edward Turner retired in 1962 after 26 years with Triumph. Management teams who replaced him had a hard time of it, although one new manager, Harry Sturgeon, showed great promise.

“I think Sturgeon was the best man Triumph had,” Coleman recalls. “He told me he never again wanted to hear me complaining about not getting enough motorcycles. He was going to do something about production." But Sturgeon, a cancer victim, died soon after.

Coleman recalls the difficulty in coaxing Triumph to update its older models, although the three-cylinder Trident, the first Triumph Multi, finally appeared in 1968. Coleman says he spent six years trying to ramrod through the idea of a rejuvenated Bonneville Twin of 750cc displacement with disc brakes and other refinements. Management favored a more expensive overhead cam Bonneville. When Triumph’s five-speed Bonneville finally appeared in 1972, Coleman believes it was at least four years late.

By that time Triumphs had another problem: a serious decline in the workmanship that had once been their trademark. Quality control was gone. American dealers complained that new Triumphs, “leaked oil everywhere but out the headlights.” Pat Owens, who was a service manager at Johnson Motors for 11 years, and who finally quit rather than see the beloved marque continue to take a beating, agrees the deterioration really set in during 1971.

Perhaps it was the prevailing mood in socialistic, financially-troubled England at the time that made the average workman dissatisfied and restless. The Triumph workers were no different. Coleman could see it when he toured the assembly line: workmen were playing cards during working hours, generally “goofing off.” The mother of a young female worker wrote a tart letter to the management: her daughter was losing her paycheck during card games on the job; couldn’t something be done?

(Continued on page 76)

Continued from page 59

By then Triumph’s parent company, BSA, had sold off much of its rapidly-sinking empire merely to stay afloat. But in other ways the group was not frugal at all. At a time, for instance, when the various motorcycle-producing factories were badly in need of renovation, the group instead spent £750,000 opening a lavish “development center.’’ Exactly what was under development was unclear; certainly no new motorcycles appeared.

Mistakes multiplied. An Ariel tricycle moped was developed at a cost of millions, but never produced. A new 350cc Triumph Bandit and BSA Fury were two more noshows. Attempts to “standardize’’ production of Tridents and BSA Rocket Threes were expensive failures. Delays continued, to the chagrin of U.S. dealers. Models expected in September, 1971, didn't arrive until the following February. Yearly losses topped $16 million and management teams were shuffled again in England and America. The Baltimore branch was closed. Somehow 1972 losses were halved, but at the expense of something else. The BSA marque vanished into oblivion, joining AJS, Ariel, Sunbeam, Velocette, Douglas, Royal-Enfield and others.

Only two English marques remained: Norton . . . and Triumph.

Triumph was clinging to life by a thread. Long gone were the once-believable claims that the Japanese were technically incapable of producing large-displacement superbikes. Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki all had successful high-powered models. Triumph, in the words of the Boston report, was backed into a comer. “In the superbike class they could retreat no further. There are no longer any new large displacement segments to which the British can make a further withdrawal.” Triumph needed financial help. This time the man with the money was Dennis Poore, 57, chairman of the English conglomerate Manganese Bronze, and, since 1966, the boss of Norton motorcycles and the Villiers industrial engine works.

Hope for the future

Joe Scaizo

When the British government withdrew financial support from Norton Triumph, the island’s dwindling motorcycle industry was dealt a severe blow. Many American observers feared that British bikes would disappear, except, perhaps, as collectors’ items. But such is not the case. Despite outward appearances, Nortons and Triumphs continue to be produced in limited quantity. Some are finding their way to the U.S., where it is hoped that they will be met by a receptive public. If this can be accomplished, it is largely because of the efforts of Dennis Poore and Roger Stange. Their views follow. -Ed.

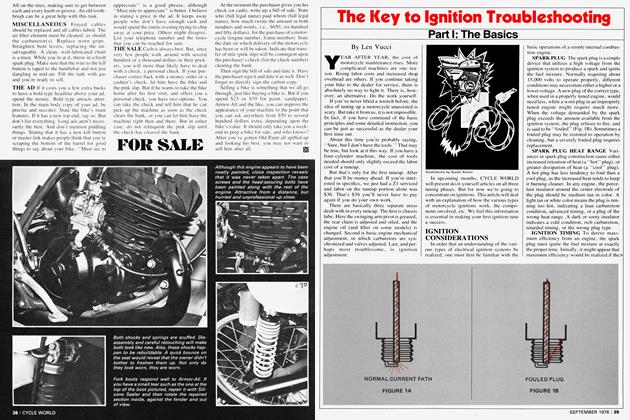

ROGER E. STANGE, president of Norton Villiers Triumph America, Inc., is a nervous man with a credibility problem. He is fighting not only to rebuild a bankrupt company, but to convince a skeptical motorcycle community that it, in fact, deserves to stay alive.

“Look,” he says, “I know everyone is rushing to bury us. There are people out there who just can’t wait to throw that first shovelful of dirt.”

Although excessive, Stange’s paranoia is perhaps pardonable, since, as he claims, “Never in my life have I heard and read more unfounded rumors and smears against a company than I heard and read last year about NVT.”

Outwardly, as he sits in his paneled office in Duarte, a Los Angeles suburb, Stange exudes confidence. But the large corporation headquarters is almost empty, the staff lately reduced to a skeleton crew of 14. There was a rumor as warm as the June weather that the facility was to be sold and NVT to shift its U.S. offices to less spacious quarters.

“Those are just the kind of rumors that damage us,” Stange sighs. “Even if they were true, the timing is so bad. We’ve been written off so many times, and had so many unfair things said about us. The life has almost been beaten out of us. We’re down but not quite out. Buyer confidence in us is down. Our dealers must be wondering what’s going to happen next if all these bad things they keep hearing are true.

“Look, our dealers are getting Bonnevilles and Tridents. And they’re selling them. Most of the dealers say they are the finest Bonnevilles they’ve seen in 10 years.”

And another thing, he goes on, is that ardent, old-line Triumph supporters have never been more dedicated. This is gratifying. There are more loyalists out there than anyone imagined. Many dealers seem to be buying up spare parts for Triumphs, regardless of year. They can’t seem to get enough of them. Even basket cases are in demand. And individuals like Brian Slark in Calif. and Jack Wilson, a veteran Triumph dealer in Dallas, are manufacturing their own line of Triumph spares. Demand is so great that Wilson’s company, Tri-Power Products, did business last year in 40 different states.

Trade Tech College in Los Angeles received an urgent telephone call the other day from a motorcycle dealer in Northern California asking if students were still being trained to repair British motorcycles as well as Japanese ones. His need for a Triumph mechanic just wouldn’t wait.

Stange sights these examples and others to convince skeptics that interest in Triumph motorcycles is unflagging, even growing. But his biggest job is to convince them that the British motorcycle industry has a future as well as a past.

Certainly there have been massive layoffs at NVT, he says, but the nucleus of the organization remains intact. Stange still has his two top associates, Tom Coates and Bob Try on.

The situation seems to be that the 700 members of the workers’ cooperative at Meriden are now in the middle of their twoyear pact with NVT to produce 500 Triumphs per week. The agreement is said to expire in March of 1977, at which time the workmen will be free to renegotiate with NVT, or perhaps to continue building Triumphs and marketing them themselves.

Stange says that NVT’s original deal with Meriden was for two years, but that the agreement has already been modified many times.

Meanwhile, going flat-out to rebuild NVT is Stange’s boss, Dennis Poore.

Last December, thanks to additional bank and government loans exceeding a million dollars, Poore set up a new companywithin NVT. Called NVT Limited, according to an announcement, it was established for the purpose of manufacturing motorcycle spares, continuing existing important precision engineering contract work, and obtaining additional similar contracts.

A retired racing driver, an English jingoist who wore his patriotism on his sleeve and who knew his Kipling and often quoted it (“England is a garden and such gardens are not made, by singing ‘Oh how beautiful,’ and sitting in the shade”), and an energetic and dynamic figure who pushed himself 18 hours a day, Poore, in 1973, became the selfappointed savior of British motorcycling.

With the help of government funds, he offered to buy Triumph motorcycles, and all else that was left of the ravished British Small Arms group, to be merged into a powerful union to be called Norton Villiers Triumph (NVT). This would be the rebirth of the British motorcycle industry.

Poore inspired confidence; at Norton, he had turned an apparently dying company around in less than 10 years and made it modestly profitable. He’d also packaged a major deal wherein John Player’s cigarettes sponsored Norton’s racing team.

But to long-time Triumph loyalists, Poore and Norton were dubious saviors at best. Since the Edward Turner days Norton and Triumph had been rivals in much the same way that Chevrolet and Ford are. What would Edward Turner have said if he’d known that Norton was riding to Triumph’s rescue? But Turner had died the year before at age 72.

The NVT merger went through, and everyone involved was caught up in a feeling of enormous optimism. It must have been the same as when Jack Sangster bought Triumph years earlier. Dennis Poore had big plans: an exotic Cosworth Norton would be built, and a hush-hush Wankel Triumph, among other things. Poore’s American man, Roger Stange, announced that a red-hot U.S. management team, led by Terry Tieman, was quitting the Yamaha International Corp. to work for NVT. (Their tenure was brief; they remained at NVT for less than a year).

The optimism soon disappeared. It disappeared, in fact, in late 1973 when Poore announced the closure of Triumph’s 36-yearold Meriden plant. He wanted to switch motorcycle production to his two other factories in Small Heath and Wolverhampton. Economics dictated that NVT could not

afford to have three plants operating at once.

Economics be damned, declared the union-backed Meriden workmen, who saw only that they were losing their jobs. No motorcycle fans, they barricaded the plant and refused to leave. Barricaded inside with them were the latest batch of Triumphs, all due for imminent shipment to America.

Poore, at this point, could have called up the cops and had them storm the place, drive out the barricaded workmen and claim his Triumphs. But government officials urged him not to; the government, after all, was helping NVT financially and was sensitive to public opinion in the trade uniondominated midlands.

What followed is almost a story in itself, a horror story as far as Norton Villiers Triumph was concerned. In brief, barricading tactics lasted on and off into 1975. It became a public issue in England. As public pressure rose, it indirectly resulted in two general elections. Finally, following several more government investments, one loan of £4 million was used to start “workers cooperative” at Meriden. Every worker, in effect, was a co-owner of the operation.

(Continued on page 103)

“In addition, another subsidiary company of NVT not previously concerned in the motorcycle business and now renamed NVT Motor Cycles Ltd., will assume worldwide distribution functions of Norton Triumph Ltd. . . . The company will also be responsible for continuing the development work already begun by Norton Triumph Engineers. . . .

“The long-term availability of spare parts is assured. NVT Engineering is a business almost solely to manufacture motorcycle spares and to rebuild dealer stocks to acceptable levels . . .

Commenting on the future, the announcement continues optimistically, “Prototype work on an exciting range of motorcycles will now commence . . . the Street/Trail 125; the twin-rotor Wankel; the T180 900cc Trident; and the Cosworth-designed Challenge . . . (but) the project nearest completion is the production of a highly competitive moped. ...”

Stange says that tests of the Norton Cosworth have been “highly promising,” with minor gearbox troubles as the only complaint.

V‘We have a future, a very good future,” he continues. “Personally, for the first time in almost three years, I have a real hope for the future.”

So much is going on with NVT in America, but Stange says he can’t release the details yet. Letters havfe gone out to the existing dealer network about the plans, but for the time being confidentiality must be maintained. In the meantime, Stange will talk about anything else if it will help silence those ridiculous rumors about the Triumph and Norton marques vanishing. Errors,

terrible business errors, were made in the past, Stange agrees, but what have they to do with the future? Certainly there are problems, problems that he can’t ignore or minimize. Still, according to Stange, “If anyone in the world has the ability to solve them, it is Dennis Poore.”

“Not 10 men in all of England could do what Poore has done.”

Stange says that he is in almost daily contact with Poore, via either long-distance telephone or Telex. According to Stange, “Dennis works 18-hour days. Personally, I can’t go on that little sleep. But we’re working hard here. And I’m not working this hard to see the whole thing sink.”

“Anything worth accomplishing is always a hard struggle. ”

As president of NVT America, Stange is working specifically to shore up dealership relations that may have grown thin during the 18 months of labor standoffs in England. These resulted in late deliveries of motorcycles and in some cases none at all. And, obviously, if NVT is to survive at all, it must hold onto its existing dealers and convince them that there is a future with Triumph.

Dealers were asked if they thought Triumph would survive, or fade away like the rest of the British industry. They were also asked whether spare parts would continue to be available.

The response was interesting. All who were contacted expressed strongly the belief that Triumph would always survive. At least one, however, wondered if NVT would.

One Pasadena, Calif., dealer of 28 years claimed that the latest Bonneville is probably “one of the best Triumphs ever made.

“Workmanship and quality control are really good. Maybe the workers have their pride back. Even the cases are nicely buffed and polished.”

Another Calif, shop owner, this one from Bellflower, said, “The new Bonnevilles don’t leak oil and are a hell of a lot more troublefree than before. We’re having great customer response from them. ” He also said he was supporting NVT. “They’re talking about doing lots of things. The best thing they can do is cut their overhead. People say, ‘Well, they’re broke.’ And I say, ‘Oh, sure. Just like Social Security is broke. Lockheed’s broke and New York City’s broke.’ But somehow'things still keep going on.” A queried Salt Lake City dealer replied, “I’ve relied on Triumph for the past 18 years. I guess I’ll continue to. We’re getting all the motorcycles and spares we need, and they’re on time.” He, too, had appreciation for the latest Bonnevilles.

And in Dallas, Jack Wilson, the owner of Big D Triumph, said, “They ain’t going out of business. The future is looking good.” In Michigan a dealer said, “I thought they would disappear last year. But they are still around. I guess you have to give Triumph credit for that.”

A Maryland Triumph dealer expressed no confidence in NVT management, but said he looked forward to the day when the Meriden workmen had the assets to run the company on their own.

“In this country there will always be a market for well-built twin-cylinder motorcycles,” he went on. “We’ll always be able to sell, say, 26,000 Triumphs a year.

“Antiquated 13-year-old designs turning customers off? No way. No one has really thought much about the customers. You can’t imagine the look on the face of a customer who hears that his three-year-old Japanese bike is out of production. But at Triumph we don’t have that problem. We have a unique bike; we’re in a unique industry. We’re here to stay.”

Continued from page 77

But the long delay had ruined Poore’s optimistic plans for NVT. If he was still to resurrect the stale British industry, he would need additional governmental capital.

But his request of mid-1975 was refused. The latest British government, not as labororiented as previous ones, noted that £25 million of public money had so far been squandered on the motorcycle industry and NVT. That was enough.

About this time, too, the highly-damaging Boston Consulting Group's report appeared. By comparing it to the Japanese, the report crucified the British motorcycle.

The report makes devastating comparisons: The average Honda worker produced more than 100 motorcycles and 20 cars a year, allowing Honda to achieve $36,000 of value per man. But in the tiny British industry, with its outmoded equipment, one workman was lucky to produce 10 machines a year. His value was put at roughly $2400.

Matters were so bad, the report contends, that even if investment money were forthcoming and sales picked up, deficits would be recorded well into the 1980s.

But one of the last conclusions was most damaging, and showed how far Triumph in particular had fallen: “There must be some doubt as to whether the British can produce a design which will be so evidently superior that it can overcome in particular the British reputation for poor reliability.”

Poore rallied against the government, charging duplicity. He was angry about the cessation of funds and blamed it for leading NVT to “the brink of disaster.” Although his charges may have been justified, everyone was by now sick of the names Triumph and Norton.

Motor Cycle News lashed out: “Why has the once bright star of the British motorcycle industry collapsed into such a state?”

Answering its own question, the paper fumed, “The attitude of the industry seemed to be to take as much profit as possible. The need to plough a little back in wasn’t considered necessary.

“Japan’s arrival on the British scene spelled a warning which the British managers didn’t take seriously. . . . They didn't take that warning.”

Was it finally the end of Triumph?

As this is written, both Dennis Poore and Roger Stange say no, that plans to save Triumph and the British industry are afoot, although they can’t be specific.

They point to the fact that Triumph Bonnevilles are, in fact, rolling off the production lines of the workers co-op at Meriden at the rate of 300 a week, and finding their way to America.

What they really are saying is that, after 89 wearying years, Triumph’s name is still alive, however barely. The question is, does anyone still care?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue