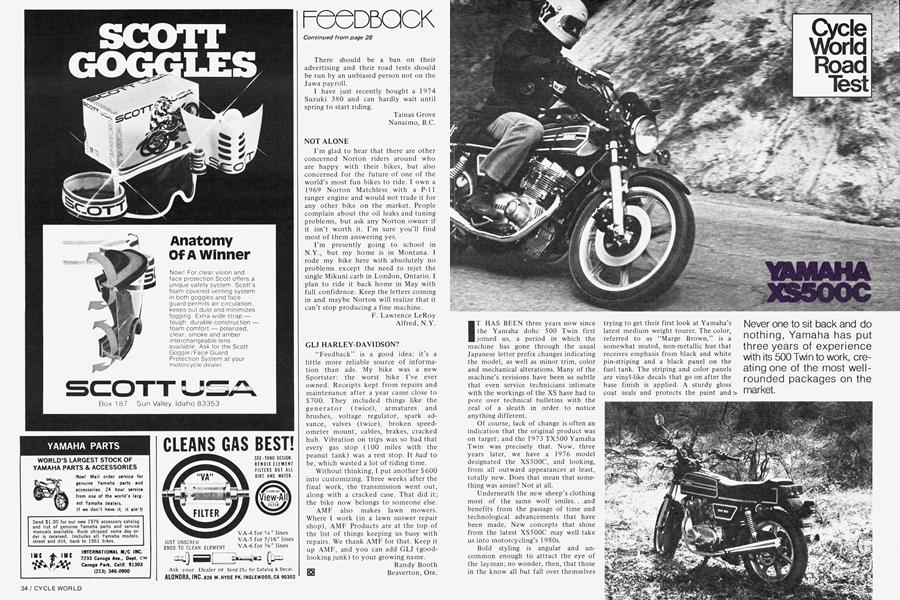

YAMAHA XS500C

Cycle World Road Test

Never one to sit back and do nothing, Yamaha has put three years of experience with its 500 Twin to work, creating one of the most wellrounded packages on the market.

IT HAS BEEN three years now since the Yamaha dohc 500 Twin first joined us, a period in which the machine has gone through the usual Japanese letter prefix changes indicating the model, as well as minor trim, color and mechanical alterations. Many of the machine's revisions have been so subtle that even service technicians intimate with the workings of the XS have had to pore over technical bulletins with the zeal of a sleuth in order to notice anything different.

Of course, lack of change is often an indication that the original product was on target; and the 1973 TX500 Yamaha Twin was precisely that. Now, three years later, we have a 1976 model designated the XS500C, and looking, from all outward appearances at least, totally new. Does that mean that something was amiss? Not at all.

Underneath the new sheep’s clothing most of the same wolf smiles. . .and benefits from the passage of time and technological advancements that have been made. New concepts that shine from the latest XS500C may well take us into motorcycling’s 1980s.

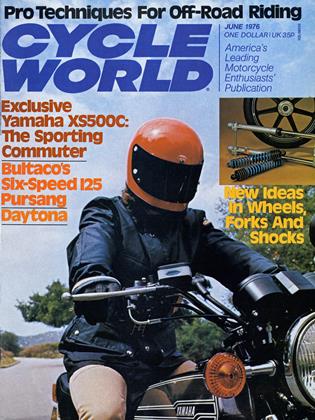

Bold styling is angular and uncommon enough to attract the eye of the layman; no wonder, then, that those in the know all but fall over themselves

trying to get their first look at Yamaha's latest medium weight tourer. The color, referred to as "Marge Brown," is a somewhat muted, non-metallic hue that receives emphasis from black and white pin-striping and a black panel on the fuel tank. The striping and color panels are vinyl-like decals that go on after the base finish is applied. A sturdy gloss coat seals and protects the paint and imparts a handsome sheen to the surface. Some onlookers we talked to would have preferred a brighter color, while others thought the conservative shade added a touch of class. We tend to agree with the latter.

It’s obvious that an integrated styling concept was sought, because the uniquely shaped and larger (up from 3.4 to 4.0 gal.) steel fuel tank flows nicely into the seat shape. The rear section of the seat —which is one of the most comfortable on which we’ve ever planted a posterior—is designed to accommodate a huge (by motorcycle standards) tail section, a two-bulb taillight and the angular, flat-surfaced plastic fender. Up front, the fender is again plastic, with none of the usual braces and mounting brackets. This type of material won’t rust, reduces weight and resists dings or bending. We know that plastic is old-hat for off-road machinery, but this is a first for large-bore, streetgoing Japanese equipment.

The only item that looks like an afterthought and spoils the interesting tail treatment is the license plate bracket and light. With a little more time, Yamaha will perhaps figure a way to achieve the style without the wart.

Cast aluminum wheels are of the same type as those found on the RD400 and the soon-to-be-released XS750 Triple. The wheels impart their own touch of newness to the machine and make for simpler cleaning and maintenance. A few grams heavier than their spoked, steel-rimmed counterparts, the cast wheels have the advantage of extra rigidity that comes to be appreciated during high-speed maneuvers. Yamaha has two suppliers who produce the wheels for them; both make careful inspections of the one-piece castings to guard against flaws. Machining is critical, but is done very accurately to ensure concentricity and runout, additional benefits of this type of wheel.

Although handling feels a touch nimbler and more positive than on previous models, the frame has gone basically unchanged, with the exception of new bracketry and mounting locations for altered external components. So we must look to other causes for the improved handling. There are the stiffer wheels, of course, and the suspension components, specifically the front forks. Previously, units came from Kayaba, the largest manufacturer of hydraulics in Japan. This time around, however, Showa supplies the forks, built to Yamaha’s own specifications as regards cost and performance.

The specs for the 1976 models must have been far more demanding, because the new forks work superbly in just about every condition we could get the bike into. They don’t ignore the little bumps in favor of the large ones, and vice versa. The units simply work beautifully on a large variety of surfaces at varied rates of speed. This performance transmits itself into the other handling qualities, producing a noticeable improvement over last year.

As a bonus, the front disc brake caliper is now mounted behind the fork leg, keeping the mass to the rear of the axle center line, which cuts down on steering inertia. It all contributes to a better-handling motorcycle, proving that little things do mean a lot. In general feel and performance, these forks reminded us a great deal of the units found on the Yamaha RD400C that we recently tested.

Unfortunately, we don’t have such glowing praise for the rear shocks. It isn’t that the dampers on the 500 are all that bad, it’s just that the RD400 set a precedent that has us spoiled. It had very good units for original equipment, but these shocks aren’t in the same league. They work well as far as absorbing little irregularities goes, but have a tendency to pogo a bit when the going gets tough. Experimenting with the five-position preload settings, we wound up with the shocks in the stiffest position most of the time to try and quell some of the wallow produced in highspeed cornering. With two on board, the “hard” setting will be mandatory just to eliminate bottoming of the components at intersection dips and the like. Incidentally, no spanner wrench is included in the otherwise complete toolkit, so before one sets out to adjust the shock preload settings, he’d better bring along the proper tool.

On one stretch of our favorite mountain highway, we were well into the 80-percent bracket of our ability and feeling quite comfortable with the 500. There is no reason to fear premature grounding of the stands or pegs because Yamaha has worked hard to tuck them out of the way. In fact, when things do start touching, the tires are into their last percentage of grip and things are fast becoming marginal. Touch a peg and you’ll be wise to roll off the throttle.

In a series of bends where the bike must be flicked from one side to the other, the weight of the 500 makes itself known to one used to a machine in the RD350 category. On the other hand, a rider with much time on a big Four will feel as though he’s riding a lightweight.

Another aspect of performance that Yamaha has looked into better is braking. It is now trendy to include a rear disc brake as part of the package on high-performance street bikes. In the case of the new 500, the cast alloy wheels were easier to produce and less expensive if they were manufactured without a molded-in brake drum surface. That necessitated a rear disc unit to go along with the front one the model has always had.

Discs and calipers are new, not pirated from a previous model. Though the calipers appear identical, they are slightly different internally and utilize different puck material front and rear. Because brake loading and forward weight transfer vary the force needed at each end, Yamaha carefully selected the right combination to achieve the right feel front and back. The “designed-in” percentage compensation will help eliminate unexpected wheel lock-ups in wet weather riding and on minimal traction surfaces.

Although not standard equipment, an optional disc brake and caliper assembly that will create a dual-disc front brake arrangement for those so inclined, is available through Yamaha dealers. Cast “lugs” on the fork leg permit easy installation of an extra disc and caliper for performance-oriented owners. The 500 is heavy enough that dual front stoppers make a noticeable improvement in braking performance.

Tires too permit experimentation. Shod with Bridgestones fore and aft, our test machine had a tendency to follow rain grooves more than we would have liked. The compound should wear very well because it is on the hard side. Even so, the 3.25-19 ribbed front and 4.00-18 rear “Superspeeds” grip surprisingly well on both wet and dry pavement. They wouldn’t be the tires to go production racing on, but they’re a good, all-around compromise.

Because the seat is so well-padded, shorter riders will find it hard to support the machine while stopped without leaning off a bit. This problem is a difficult one to get around. If some of the padding is removed, the seat is uncomfortable. With all the stuffing, the seat is on the tall side, but one of the best there is for all-day comfort.

In the past, instruments were mounted in a single bracket. Now the tach and speedometer are once again separate, with a warning light panel and ignition switch between them. The warning lights include two large turnindicator arrows at the top, underscored by what may be the biggest oil pressure and neutral lights ever put on a motorcycle. The blue high-beam indicator bulb is in the face of the 9000-rpm redline tach. Both the tach and speedo are lit beautifully at night with a soft green glow. The stop lamp warning light has at last been deleted. We always found it distracting and won’t miss it a bit.

As with the RD400C, turn indicators are self-canceling and make it impossible to travel for miles down a highway with a blinker going. The thumb-operated switch self-centers after it’s pushed right or left. Manual canceling is achieved by pushing the knob straight in. If the unit is allowed to cycle on its own, it will flash the signals for about 1 5 seconds at cruising speeds, or 300 feet around town. In California, many of the roads have warning messages painted on the road surfaces. We found that if we activated the signals when approaching an intersection’s painted proclamation “STOP AHEAD,” the unit would cancel itself just about the time we were completing our turn. This feature has been long overdue and is vastly superior to the reminding beepers that come with some machines.

The ignition key is double-sided and operates the locking, flip-up seat and the fuel-tank cap. The cap is now nearly flush with the surface of the tank and is hinged at the rear so that it can’t flip up in the event of an accident and injure the rider in a vital area.

Handlebars are too high for comforiable riding at higher speeds without a fairing because they put the rider straight up in the wind blast. Handgrips are perfect and placement of all control buttons and switches is ideal. Everything is clearly labeled per government regulations. We thank Yamaha for including an on/off headlight switch, but would appreciate a louder horn and amber lenses for the rear turn-indicator lights.

The dual-cammed, four-valve-percylinder, four-stroke Twin is a marvelously compact unit that has proven to be less troublesome than one might have expected at first. There is no question that there are a lot of pieces turning and bumping around inside the engine. A listen to the top end will tell anyone that it’s busy in there. But among all the chains and gears and bearings and oil seals, there lurks harmony, and that counts heavily when the miles add up.

If, in the past, there was any problem with the 500 Twin that surfaced on enough occasions to warrant furrowed foreheads, it lay with the cam case and cylinder head assemblies, which were separate pieces. Apparently oil seepage became a problem if initial service procedures were not carried out properly, or at all. Checking the head bolt torque after initial break-in was critical. . .and time-consuming. Some dealers did it improperly and certain owners neglected it altogether. Now the cylinder head and cam case are cast as one piece to eliminate the problem. The new part will fit the older machines and simplifies service checks for the mechanic.

In Japanese tradition, the Twin’s crankcases split horizontally. The crankcase is a one-piece forged affair that rides in three large plain-type main bearings. Crank throws are 180 degrees apart and the opposite firing order makes for an unusual stacatto sound. Flywheel weight has been increased this year by 10 percent to help smooth power delivery and lessen drive train snatch. But even with the increase, flywheels are on the small side, since the 180-degree crank configuration doesn’t require massive weights to balance lower end.

Double sprockets on the cam ends are driven by a double-row chain that runs through idler sprockets and off of a drive sprocket on the crankshaft. There are two inlet and exhaust valves per cylinder and redesigned ports on the 500C version. Piston crowns are 1mm shorter and reduce compression from 9.0:1 to 8.5:1. Finger-type cam followers are used, while valve clearance is adjusted by turning screws on the valve ends. The lightweight valve train accounts in part for the 9000-rpm redline; a rigid, finely balanced crankshaft does the rest.

We know that annoying vibration is an innate quality of a Twin. There’s no way around it without some sort of counteracting force that negates the original vibes. Yamaha’s antidote is referred to as an “Omni-Phase” balancer, but in reality is not much more than a given weight revolving opposite the crankshaft. Driven off the left end of the crank by a sprocket and chain, the dynamic balancer nestles in a cavity behind the cylinders in the crankcase.

An electric starter motor finds its place behind the balancer; things get turning at the press of a button via an additional chain and sprocket.

There are lots of oil cavities within the engine and two dip sticks to check levels. The high-capacity oil pump is a two-stage, trochoidal unit that pressurelubricates valve train, transmission and crankcase. Oil levels are necessary in the primary drive case, gearbox, crankcase, and the starter, alternator and balancer cases. This year a PCV valve has been added, making the engine rebreathe its own harmful fumes over and over again.

Keihin carbs are gone, as are their push-pull throttle cables. Mikuni has come to the rescue with new BS38 diaphragm units, aiding starting, idle and low-speed response. The air cleaner is readily accessible by removing two thumb screws and a metal lid from the still airbox; a spring clip pops out and the fuzz/foam filter can be removed for cleaning. The engine is happiest on low-lead fuel, but will run on unleaded or premium in a pinch. Two fuel petcocks are fitted; reserve positions must come into play at around the 150-mile mark on the trip odometer.

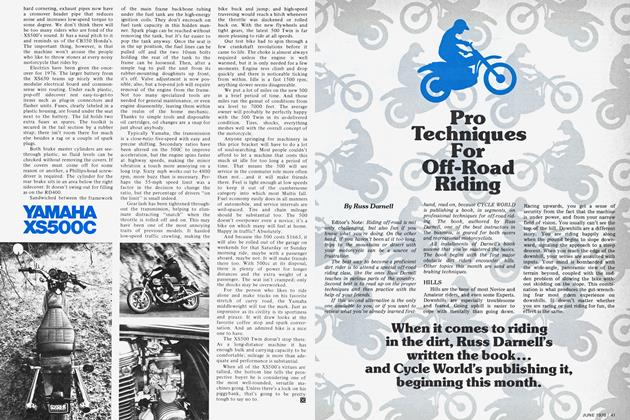

In addition to being tucked well out of the way for greater lean angles during hard cornering, exhaust pipes now have a crossover header pipe that reduces noise and increases low-speed torque to some degree. We don’t think there will be too many riders who are fond of the \ XS500’s sound. It has a nasal pitch to it and reminds us of the CB350 Honda’s. The important thing, however, is that the machine won’t arouse the people who like to throw stones at every noisy motorcycle that rides by.

SUSPENSION DYNO TEST

Description: Showa tront tork, HD-31 5 oil Fork travel, in.: 5.5 Spring rate, lb./in.: 30 Compression damping force, lb.: 10 Rebound damping force, lb.: 45 Static seal friction, lb.: 4

As far as Japanese manufacturers go, Yamaha is clearly the leader in roadster fork design. Compression damping on the XS500 units is perfect. Spring rate is well suited to the machine's weight (there is no preload) and remains linear until the forks bottom. This is possible because the spring itself does not coil bind until it is compressed 8 in. Rebound damping is excesswe and should be 10 lb. less. On a heavy road bike this has mini mal effect on both ride and control. Teflon fork seals have reduced seal drag to 4 lb. and allow the forks to react pro perly to the road surfaces.

Description: Showa shock Shock travel, in.: 2.5 Wheel travel, in.: 3.25 Spring rate, lb.Iin.: 100 Compression damping force, lb.: 20 Rebound damping force, lb.: 55

Remarks: Compression damping is fine. Spring rate is marginally ltght. It's okay for solo riding, but is not sufficient for packing double. Rebound damping should be 115-120 lb. to allow stability when cornering hard. As is, the bike wallows any time the rider enters a turn near the limit of traction. Hard acceleration, brak ing, or rough pavement in the corner compounds the problem. The best solu tion is a pair of accessory shocks with 1 10-lb. springs, 20 lb. of compression damping and 1 25-lb. rebound damping.

Tests performed at Number One Products

YAMAHA

XS500C

$1663

Electrics have been given the onceover for 1976. The larger battery from the XS650 teams up nicely with the modular electrical board and commonsense wire routing. Under each plastic, pop-off sidecover rest easy-to-get-to items such as plug-in connectors and flasher units. Fuses, clearly labeled in a plastic housing, are found under the seat next to the battery. The lid holds two extra fuses as spares. The toolkit is secured in the tail section by a rubber strap; there isn’t room there for much else besides a rag or a couple of spark plugs.

Both brake master cylinders are seethrough plastic, so fluid levels can be checked without removing the covers. If the covers must come off for some reason or another, a Phillips-head screwdriver is required. The cylinder for the rear brake sits in an area below the right sidecover. It doesn’t swing out for filling as on the RD400.

Sandwiched between the framework of the main frame backbone tubing under the fuel tank are the high-energy ignition coils. They don’t encroach on fuel tank capacity in this hidden manner. Spark plugs can be reached without removing the tank, but it’s far easier to pop the tank anyway. Once the seat is in the up position, the fuel lines can be pulled off and the two 10mm bolts holding the rear of the tank to the frame can be loosened. Then, after a simple tug to pull the unit from its rubber-mounting doughnuts up front, it’s off. Valve adjustment is now possible, also, but a top-end job will require removal of the engine from the frame. Not too many specialized tools are needed for general maintenance, or even engine disassembly, leaving them within the realm of the home mechanic. Thanks to simple tools and disposable oil cartridges, oil changes are a snap for just about anybody.

Typically Yamaha, the transmission is a close-ratio five-speed with easy and precise shifting. Secondary ratios have been altered on the 500C to improve acceleration, but the engine spins faster at highway speeds, making the minor vibration a touch more annoying on a long trip. Sixty mph works out to 4800 rpm, more buzz than is necessary. Perhaps the 5 5-mph speed limit was a factor in the decision to change the ratio, but the percentage of drivers “on the limit” is small indeed.

Gear lash has been tightened throughout the transmission, helping to eliminate distracting “snatch” when the throttle is rolled off and on. This may have been one of the most annoying traits of previous models. It hassled low-speed traffic crawling, making the bike buck and jump; and high-speed traversing would reach a hitch whenever the throttle was slackened or rolled back on. With the new flywheels and tight gears, the latest 500 Twin is far more pleasing to ride at all speeds.

Our test bike had to spin through a few crankshaft revolutions before it came to life. The choke is almost always required unless the engine is well warmed, but it is only needed for a few moments. Engine revs climb and drop quickly and there is noticeable ticking from within. Idle is a fast 1500 rpm; anything slower seems disagreeable.

We put a lot of miles on the new 500 in a brief period of time. And those miles ran the gamut of conditions from sea level to 7000 feet. The average owner will probably be perfectly happy with the 500 Twin in its as-delivered condition. Tires, shocks, everything meshes well with the overall concept of the motorcycle.

Anyone springing for machinery in this price bracket will have to do a lot of soul-searching. Most people couldn’t afford to let a machine that costs this much sit idle for too long a period of time. That means the 500 will see service in the commuter role more often than not. . .and it will make friends there. Feel is light enough at low speeds to keep it out of the cumbersome category into which most Multis fall. Fuel economy easily does in all manners of automobile, and service intervals are well-spaced. Tire and chain mileage should be substantial too. The 500 doesn’t overpower even a novice; it’s a bike on which many will feel at home. Happy in traffic? Absolutely.

And because the 500 costs $1663, it will also be rolled out of the garage on weekends for that Saturday or Sunday morning ride, maybe with a passenger aboard, maybe not. It will make friends there too. With 500cc at its disposal, there is plenty of power for longer distances and the extra weight of a passenger. The seat isn’t cramped; only the shocks may be overworked.

For the person who likes to ride alone and make tracks on his favorite stretch of curvy road, the Yamaha middleweight will toe the mark. Just as impressive as its civility is its sportiness and pizazz. It will draw looks at the favorite coffee stop and spark conversation. And an admired bike is a nice one to have.

The XS500 Twin doesn’t stop there. As a long-distance machine it has enough bulk and carrying capacity to be comfortable; mileage is more than adequate and performance is substantial.

When all of the XS500’s virtues are tallied, the bottom line tells the prospective buyer he is considering one of the most well-rounded, versatile machines going. Unless there’s a lock on his piggybank, that’s going to be pretty tough to say no to. [3j

View Full Issue

View Full Issue