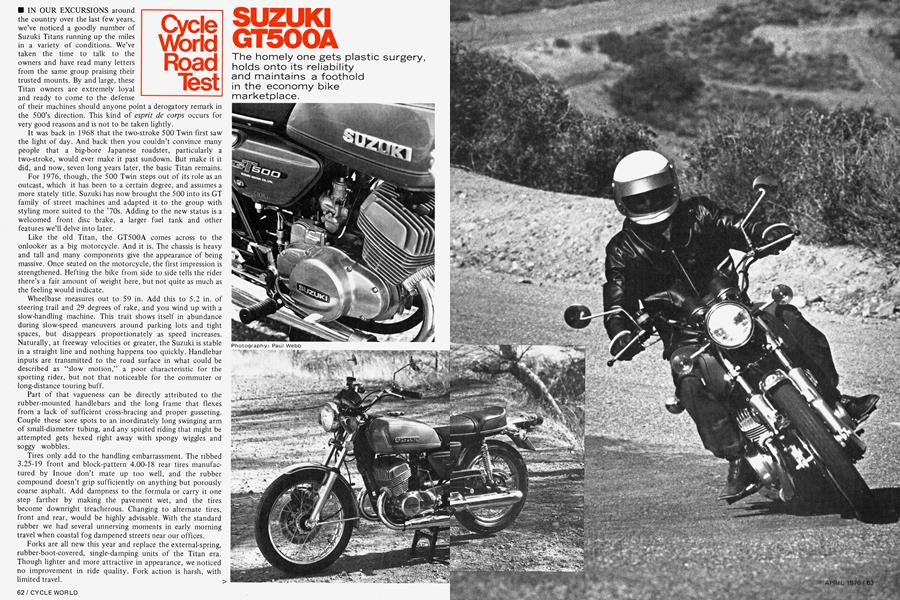

SUZUKI GT500A

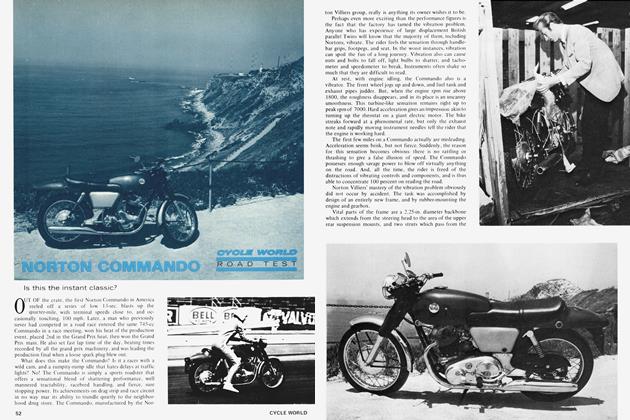

Cycle World Road Test

The homely one gets plastic surgery, holds onto its reliability and maintains a foothold in the economy bike marketplace.

■ IN OUR EXCURSIONS around the country over the last few years, we’ve noticed a goodly number of Suzuki Titans running up the miles in a variety of conditions. We’ve taken the time to talk to the owners and have read many letters from the same group praising their trusted mounts. By and large, these Titan owners are extremely loyal and ready to come to the defense of their machines should anyone point a derogatory remark in the 500’s direction. This kind of esprit de corps occurs for very good reasons and is not to be taken lightly.

It was back in 1968 that the two-stroke 500 Twin first saw the light of day. And back then you couldn’t convince many people that a big-bore Japanese roadster, particularly a two-stroke, would ever make it past sundown. But make it it did, and now, seven long years later, the basic Titan remains.

For 1976, though, the 500 Twin steps out of its role as an outcast, which it has been to a certain degree, and assumes a more stately title. Suzuki has now brought the 500 into its GT family of street machines and adapted it to the group with styling more suited to the ’70s. Adding to the new status is a welcomed front disc brake, a larger fuel tank and other features we’ll delve into later.

Like the old Titan, the GT500A comes across to the onlooker as a big motorcycle. And it is. The chassis is heavy and tall and many components give the appearance of being massive. Once seated on the motorcycle, the first impression is strengthened. Hefting the bike from side to side tells the rider there’s a fair amount of weight here, but not quite as much as the feeling would indicate.

Wheelbase measures out to 59 in. Add this to 5.2 in. of steering trail and 29 degrees of rake, and you wind up with a slow-handling machine. This trait shows itself in abundance during slow-speed maneuvers around parking lots and tight spaces, but disappears proportionately as speed increases. Naturally, at freeway velocities or greater, the Suzuki is stable in a straight line and nothing happens too quickly. Handlebar inputs are transmitted to the road surface in what could be described as “slow motion,” a poor characteristic for the sporting rider, but not that noticeable for the commuter or long-distance touring buff.

Part of that vagueness can be directly attributed to the rubber-mounted handlebars and the long frame that flexes from a lack of sufficient cross-bracing and proper gusseting. Couple these sore spots to an inordinately long swinging arm of small-diameter tubing, and any spirited riding that might be attempted gets hexed right away with spongy wiggles and soggy wobbles.

Tires only add to the handling embarrassment. The ribbed 3.25-19 front and block-pattern 4.00-18 rear tires manufactured by Inoue don’t mate up too well, and the rubber compound doesn’t grip sufficiently on anything but porously coarse asphalt. Add dampness to the formula or carry it one step farther by making the pavement wet, and the tires become downright treacherous. Changing to alternate tires, front and rear, would be highly advisable. With the standard rubber we had several unnerving moments in early morning travel when coastal fog dampened streets near our offices.

Forks are all new this year and replace the external-spring, rubber-boot-covered, single-damping units of the Titan era. Though lighter and more attractive in appearance, we noticed no improvement in ride quality. Fork action is harsh, with limited travel.

The harshness is a result of an excessively high spring rate. While BMW and Yamaha are using soft springs (15-20 lb.) with a lot of preload, Suzuki has opted for a 50/65-lb. progressive spring with very little preload in order to arrive at a comfortable ride on its touring bikes. A better choice, considering the limited travel of the Suzuki forks, would be a 30-lb spring preloaded an inch to 15 in. Altering the spring rate wouldn’t improve handling because damping is minimal, as well (see suspension dyno), but it would drastically improve the ride.

A cast-in boss on the right lower fork leg provides a mounting location for the disc brake caliper; the disc is a welcomed addition to the motorcycle, particularly since the machine now carries “GT” nameplates. Stopping distances have not noticeably improved with the addition of the disc, however. This can no doubt be traced back to the tires.

The rear brake is, as before, a single leading-shoe drum unit that is somewhat insensitive, and, on our test machine, one that squealed annoyingly despite efforts on our part to remedy the problem. We suspected a buildup of lining dust in the drum and glazing of the linings, which, as it turned out, was the case. After removal, the glaze would reappear after a short amount of use, so we lay blame on the lining material, since we couldn’t correct the annoyance in the usual manner. When the glaze returned, so did the squeal.

Rear suspension performs as we’d expect from a budget priced model. Taking the bike’s intended use into consideration, and allowing for only very conservative riding, the shocks just barely get by. Get on a rough road or ride quickly, and you will easily exceed the shocks’ capabilities. In other words, the GT500 wiggles a lot when ridden hard or when the road surface is less than ideal.

Cost is the primary reason for this. On the GT500, Suzuki opted for using an existing design that is both conservative in oil capacity and in material used. The result is inconsistent damping. Replacing the shock is about the only solution. Ride, however, can be improved (if you ride solo most of the time), by replacing the shock springs with 120-pounders. Have a dealer do it, though, because the upper mount/spring retainer is threaded on the shaft and is difficult to remove without ruining the unit.

We like the new way the GT500A presents itself to the spectator. Styling has gone from the cluttered and awkward to the clean and simple, without too many major or costly changes. The fuel tank has been upped in capacity from 3.7 to 4.5 gal. and is shaped well enough to be unobtrusive to the rider: narrow at the rear and fatter at the front. A curious black cover at the forward portion of the top of the tank is fixed in position and is a possible indication that the tank was originally designed for another machine. The fuel cap is hinged at the front, which is wrong. This creates a possible hazard for a rider involved in an accident in which the fuel cap pops open inadvertently. A simple reverse of the cap’s position would eliminate the hazard. One nice touch is a lock on the cap button, which can be left in a locked or unlocked position. The tank is now good for about 150 to 180 miles before reserve, which should run the bike another 20 to 30 miles.

The seat is okay as most Japanese seats go, but on extended trips it gets uncomfortable quicker than most riders will like. For around-town excursions no one will be too unhappy, however. But why do they have to keep installing those “hit you across the rump” passenger assist straps that are all but useless to a rider hanging on behind? We’d rather see Suzuki reinstall a passenger grab bar just behind the seat like the previous Titan had.

After all these years the Suzuki folks have given their 500 two-stroke Twin a new ignition switch location. It’s now just forward of the handlebars between the tachometer and speedometer. It was previously hidden under the left side of the fuel tank, which, as most of us know, was the old way on many machines. As a bonus to the ignition switch location, lighting controls remain about the easiest and most logically placed in the industry.

The dimmer and on/off rocker switches are shaped differently so a rider can ascertain which is which with a gloved hand, though the on/off switch comes fixed in the on position. We can’t understand why Suzuki insists on doing this to the light switches of its new street motorcycles, but the fix is an easy one.

Simply take a Phillips-head screwdriver and remove the screw holding the switch knob in place. Then clip off the plastic tab molded to the bottom with a pair of snips, wire cutters or a razor blade, and reinstall. The knob will now slide back and forth in its slot normally and you can now operate your headlight manually. Honda is another manufacturer not installing on/off controls on its lights these days, in spite of the fact that there is no federal law requiring such a feature. Though there are still several states with “lights-on” laws, many of these same states are repealing the laws upon finding out that the accident rate remains unaffected in the majority of cases. We’d thank Honda and Suzuki to quit playing cowtow to the bureaucrats and give us back our headlight switches so we can decide.

Perhaps Suzuki has been listening to some input on turn signal visibility, however, and the GT incorporates larger indicator lenses this year. In addition, rear units have been changed from red to the more visible amber. They incorporate no lane-change or self-canceling feature, but are easy to use just the same.

The instrument pod is borrowed from the other GT models and reads easily by day, though at night illumination is muddy. The bulb in the speedometer lasted only a short time before burning out. Warning lights include high beam, turn signal and neutral indication; no dazzling array, just the essentials.

We remember back in the not-too-distant past when the Titan was an under-$1000 motorcycle; startling even then when you realized that $1000 was buying 500cc of motorcycle. In fact, in its infancy the Titan was considered a two-stroke superbike capable of fairly respectable speeds. The Suzuki factory racing versions were clocking a nick over 150 mph at Daytona, and the 500-based racer was the very first two-stroke ever to win an AMA National road race with Art Baumann aboard.

Of course, by today’s standards the 500’s performance is no longer an eyebrow-raiser, and quieter exhaust and intake muffling have sliced some of the crispness off full-throttle runs. But the bike remains a reliable bargain, in spite of a price increase to $1295.

As a comparison, Kawasaki’s 500 Triple is now a $1576 machine; the Honda 500 Twin goes for $1608. The new Yamaha 500cc Single in street trim sells for $1395, and its 500 Twin will probably be in the $1600 neighborhood. About the only machines in close price proximity to the GT500A are > Kawasaki’s KZ400 commuter bike at $1239 and Honda’s CB360 Twin, which sells for $1224. Suzuki’s own GT380 will cost $55 more than its 500. There is no doubt that in today’s marketplace the GT500A remains a bargain; but let’s face it, if a bargain is going to be a cheap headache, who needs it? Fortunately, this is not the case with the GT500A. Here a buyer gets a reliable, proven machine capable of delivering thousands of miles of troublefree riding.

Where does the reliability come from? Perhaps in part from the bike’s extremely high overall gear ratio, which turns the engine at very leisurely rpm at any given sane highway speed. Running at 65 mph, the crankshaft is turning an easy 4100 rpm, well below the red area of the tachometer.

The engine is simple in concept and uses many high-quality components throughout. Much of what is inside the engine is on the hefty side, from connecting rods to crankshaft to flywheels. And it’s the large flywheel mass that makes revs build and unwind slowly; things don’t happen in an instant on the 500 when the throttle is snapped open. But the large piston mass is also what contributes to a high level of vibration, which seems to multiply dramatically as revs build to redline limits.

Three main bearings support the crankshaft load, while needle bearings are found at both ends of the connecting rod. Cylinder liners are steel and many owners report mileage well in excess of 50,000 before rebore becomes necessary. Oil delivery is via Suzuki’s very efficient and thrifty CCI system, using a plunger-type pump to meter oil to the two outer main bearings and the base of each cylinder. Oil to the main bearings mixes with the incoming fuel/air mixture and is burned. The center main bearing is lubricated by the transmission oil and cylinder walls and wrist pins have separate lube orifices. We ran more than 850 miles before the oil tank would accept a quart of injection oil, a figure we’ve grown to expect from Suzuki’s road-going two-strokes. As a side note, running exclusively on Bel-Ray SI-7 injection oil, we noticed very little visible smoke coming from the large and quiet muffler system.

Transmission ratios are somewhat peculiar and coupled > with the high overall gear ratios they make the machine a little hard to get used to, particularly in stop-and-go city traffic. Clutch slipping becomes necessary at these low speeds, and until a rider gets used to the bike, the inclination is to keep stepping on the gear lever because you think the machine is in second.

SUSPENSION DYNO TEST FRONT FORKS

Description: Suzuki GT500 fork with HD315 oil Fork travel, in.: 4.25 Spring rate, lb./in.: 50/65 progressive Compression damping force, lb.: 9 Rebound damping force, lb.: 9 Static seal friction, lb.: 18 Remarks: Forks are stiff and don't react to rough street surfaces enough to offer much rider comfort. This is due primarily to an inordinately high spring rate. The only saving factor here is that very little preload is used. Still, a 30-lb. spring with an inch of preload would drastically improve the ride. Materials used in the fork are good, but the design is totally ineffective. Construction is similar to that of an XR75 Honda fork (the damper rod has a slotted top in lieu of holes to control fluid movement). There is no hydraulic damping until the fork is within an inch of full compression or extension. The only damping present in the middle of the stroke (where the fork works most of the time), is a result of seal friction. Because of the lack of rebound damping, the forks return too quickly and top. Any sudden iifting of the front end following a bump effects steering and causes the bike to wander, especially in turns. Bottoming does not occur because of the high spring rate. There is no easy cure. There are no accessory kits available. If you are dissatisfied with the front suspension, replacement is the answer. If you consider this approach, stanchion tube diameter is 35mm.

REAR SHOCKS

Description: Suzuki GT500 shock Shock travel, in.: 2.75 Wheel travel, in.: 3.0 Spring rate, lb./in.: 146 Compression damping force, lb.: 8 Rebound damping force, lb.: 92

Remarks: Spring rate is too high for solo riding. The result isa jarring ride. A 110—120-lb. spring with a normal amount of preload would cure this. The standard spring, however, set on the softest preload position, is well suited to riding double. The ratio between compression and rebound damping is fine. But there is insufficient rebound control for the weight of spring fitted. Construction of the shock is marginal both in materials and in oil capacity. If you enjoy riding fast, we suggest shock replacement. That is the only cure for the high heat buildup and inconsistent damping of the original equipment.

Tests performed at Number One Products

SUZUKI

GT500A

$1295

In actuality, the transmission is an extension of the thought that has produced strong components in the remainder of the engine. All five gears are of a more than ample size to handle the 500’s power output, which runs in the honest 30-35-hp neighborhood. Third, fourth and fifth gear pinions are made onto the mainshaft, and first and second ride on split-needle bearings. A thin-gauge metal tray directs oil splash to the left side of the gearbox cavity for fifth-gear lubrication. A conventional spring-loaded pawl and drum-type assembly accomplishes a portion of the shifting chore, and short half-shifter forks complete the operation. The countershaft end drives both the oil pump and tachometer, which means that when the clutch is pulled in, the tachometer needle rests on 0. It only became bothersome at the drag strip when sitting on the start line and revving the engine for a go at the lights. Here the rider had to rely totally on feel to get away in the quickest possible manner.

The GT500A certainly dispels the last vestiges of the myth that a two-stroke engine can’t be torquey. This one pulls smartly without bucking from just under 2000 rpm and signs off abruptly at 6500. The machine is more comfortable if left in a higher gear under load, rather than buzzing along with the engine not pulling. The “knuckling under” seems to smooth vibration somewhat, but any serious passing, two-up riding or climbing of grades will require the use of fourth and sometimes even third gear at highway speeds.

Perhaps the worst of the vibration is transmitted through the rider’s footpegs, which are in an awkward position to begin with. It was far more comfortable for everyone who rode our test machine to simply fold down the passenger pegs and use those the majority of the time.

Carburetion remains unchanged this time around, with two 32mm Mikunis handling the job nicely. The enrichening lever is only required briefly with a cold engine. Three or four kicks of the starter lever are needed to bring the engine to life after it’s been sitting overnight, but when warm a prod or two will do. Don’t look for a starter button on this one, either, because electric starting isn’t found on this GT, nor is it an option.

The paper element air filter had to go sooner or later, and Suzuki has changed over to a double foam element complete with a newly designed airbox assembly. This, we suspect, contributes to the quieting down of the intake roar at wider throttle openings.

Also new is the ignition system, a revised PEI with an external pulser coil and internal exciter coil. Both spark plugs fire at the same time at TDC and BDC. There are no points to adjust or replace and ignition timing remains constant.

Fortunately for owners and Suzuki alike, the new GT version of the Titan retains much of what was there before, with a few new important touches. That means the nearly 1000 Suzuki dealers from coast to coast will have parts and knowledge to keep the GT bike running happily without the additional hassles that an all-new model often creates. Steady sales and loyal owners have proven that the 500 Twin has a definite niche in the marketplace. Though the bike has its weak points, and areas that could be improved, it remains a simple, trustworthy motorcycle for the rider who doesn’t want to lay out a hunk of his life savings to own it. That niche in the marketplace remains, to be sure, and the GT500 Twin fills it better than ever. 0