THE SEASON WAS STILL young as Harley-Davidson team rider and dirt track specialist Corky Keener turned his thoughts to the final segment of the AMA National calendar. Specifically, he was thinking of not one, but two Mile dirt track Nationals, both run within the narrow confines of a single 24-hour period. It would be a muscle-flexing exercise for all involved, and only those with an abundance of early season calisthenics to their credit would be listed among the survivors come late Sunday afternoon in Indianapolis.

Corky was eager, because the Mile ranks as his favorite type of race, and the Indy Mile heads the list. As a member of the H-D team, Corky was commenting on the probable survival rate of equipment, since most machines would have to run nearly 100 miles, counting practice, qualifying , heat races and the finals. At the time he felt it would be necessary to use a different and fresh race bike for each day's events, and he showed concern for the privateers who had no such alternative.

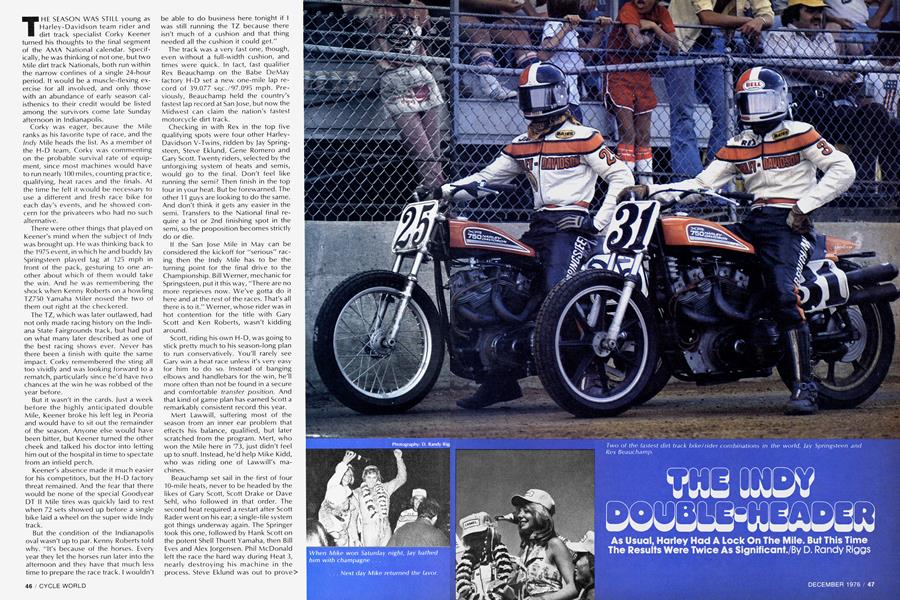

There were other things that played on Keener's mind when the subject of Indy was brought up. He was thinking back to the 1975 event, in which he and buddy Jay Springsteen played tag at 125 mph in front of the pack, gesturing to one another about which of them would take the win. And he was remembering the shock when Kenny Roberts on a howling TZ750 Yamaha Miler nosed the two of them out right at the checkered.

The TZ, which was later outlawed, had not only made racing history on the Indiana State Fairgrounds track, but had put on what many later described as one of the best racing shows ever. Never has there been a finish with quite the same impact. Corky remembered the sting all too vividly and was looking forward to a rematch, particularly since he'd have two chances at the win he was robbed of the year before.

But it wasn't in the cards. Just a week before fhe highly anticipated double Mile, Keener broke his left leg in Peoria and would have to sit out the remainder of the season. Anyone else would have been bitter, but Keener turned the other cheek and talked his doctor into letting him out of the hospital in time to spectate from an infield perch.

Keener's absence made it much easier for his competitors, but the H-D factory threat remained. And the fear that there would be none of the special Goodyear DT II Mile tires was quickly laid to rest when 72 sets showed up before a single bike laid a wheel on the super wide Indy track.

But the condition of the Indianapolis oval wasn't up to par. Kenny Roberts told why. "It's because of the horses. Every year they let the horses run later into the afternoon and they have that much less time to prepare the race track. I wouldn't be able to do business here tonight if I was still running the TZ because there isn't much of a cushion and that thing needed all the cushion it could get."

The track was a very fast one, though, even without a full-width cushion, and times were quick. In fact, fast qualifier Rex Beauchamp on the Babe DeMay factory H-D set a new one-mile lap record of 39.077 se,c./97.095 mph. Previously, Beauchamp held the country's fastest lap record at San Jose, but now the Midwest can claim the nation's fastest motorcycle dirt track.

Checking in with Rex in the top five qualifying spots were four other HarleyDavidson V-Twins, ridden by Jay Springsteen, Steve Eklund, Gene Romero and Gary Scott. Twenty riders, selected by the unforgiving system of heats and semis, would go to the final. Don't feel like running the semi? Then finish in the top four in your heat. But be forewarned. The other 11 guys are looking to do the same. And don't think it gets any easier in the semi. Transfers to the National final require a 1st or 2nd finishing spot in the semi, so the proposition becomes strictly do or die.

If the San Jose Mile in May can be considered the kickoff for "serious" racing then the Indy Mile has to be the turning point for the final drive to the Championship. Bill Werner, mechanic for Springsteen, put it this way, "There are no more reprieves now. We've gotta do it here and at the rest of the races. That's all there is to it." Werner, whose rider was in hot contention for the title with Gary Scott and Ken Roberts, wasn't kidding around.

Scott, riding his own H-D, was going to stick pretty much to his season-long plan to run conservatively. You'll rarely see Gary win a heat race unless it's very easy for him to do so. Instead of banging elbows and handlebars for the win, he'll more often than not be found in a secure and comfortable transfer position. And that kind of game plan has earned Scott a remarkably consistent record this year.

Mert Lawwill, suffering most of the season from an inner ear problem that effects his balance, qualified, but later scratched from the program. Mert, who won the Mile here in '73, just didn't feel up to snuff. Instead, he'd help Mike Kidd, who was riding one of Lawwill's machines.

Beauchamp set sail in the first of four 10-mile heats, never to be headed by the likes of Gary Scott, Scott Drake or Dave Sehl, who followed in that order. The second heat required a restart after Scott Rader went on his ear; a single-file system got things underway again. The Springer took this one, followed by Hank Scott on the potent Shell Thuett Yamaha, then Bill Eves and Alex Jorgensen. Phil McDonald left the race the hard way during Heat 3, nearly destroying his machine in the process. Steve Eklund was out to prove> he can "Mile" with the best of them, but after an exciting scrap with Mike Kidd, his Harley digested itself and went on the DNF list. Kidd won it, followed by Steve Morehead, Skip Aksland and Chuck Palmgren. Roberts edged the troops in the final heat.

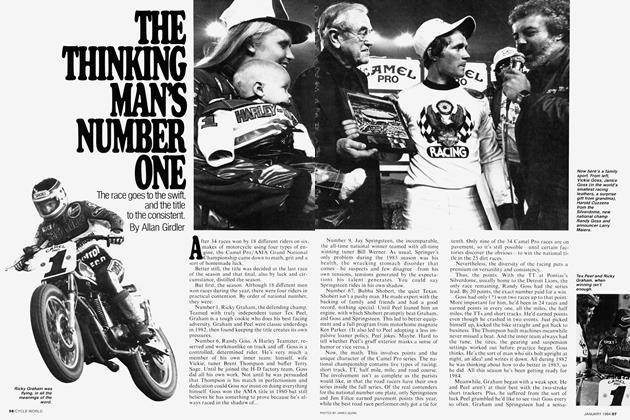

THE INDY DOUBLE-HEADER

As Usual, Harley Had A Lock On The Mile. But This Time The Results Were Twice As Significant.

D. Randy Riggs

There were probably plenty of spectators who had their money on Beauchamp, what with his new one-mile record and a win in the fastest of the six preliminary races. But those who know Rex knew something was not quite right. He'd burned up a clutch in qualifying and had troubles with a mag in the heat. And it's niggling little incidentals like that that can psych Rex right out of the ballgame.

While thousands enjoyed the Indiana State Fair going on outside the dirt oval, an even more exuberant bunch packed the grandstands and infield to watch AMA starter Phil Dyson get the 20-rider field underway with the starting light system.

Riders destined for high finishing spots let it be known right from the beginning. Mike Kidd, who has had to deal with the aggravations of poor equipment much of this season, found his match in Mert's XR. Bike and rider worked in perfect harmony to lead a good deal of the time. This particular machine had lots of tricks, a Lawwill chassis and Lectron carbs. It looked as though it had a couple of miles per hour on most of the good ones.

Clumps began forming. Up front it was Kidd and Springsteen. Slightly behind was Gary Scott, hounded by Beauchamp. Kenny Roberts had started well, but was dropping back slowly. Alex Jorgensen on the Norton, Gene Romero and Steve Morehead were all in close company. There was much in the way of incentive for Beauchamp to get by Scott (it was Scott who claimed Rex's engine at San Jose), and he did, but his charge after the leaders began too late. His rear tire had worn too much to keep up a 100-percent effort.

The real race, of course, centered around the two leading Harleys. As Mike Kidd mentioned later, he only had about eight bucks in his pocket, so he was trying extra hard to lead Springsteen each time they crossed the finish line in order to collect lap money. Naturally, the heavy duty lap money was going to come from leading across that finish line on lap 25. And Kidd, the little Texan, did it ... by about a foot. Bill Werner was already shaking his head as soon as he saw Springer leading off the final turn. "Chalk that one up to experience," he said as he went to grab the bike from his rider.

Kidd and Lawwill were elated; Springsteen showered everyone in sight with champagne. But Beauchamp looked disappointed. He'd really rather win than come in 3rd. Scott held onto his points lead by winding up 4th. Romero was 5th, Jorgy 6th and Roberts 7th. Kenny's night was a long way from over, however, as his machine was claimed (see story, page 52). To further complicate matters for officials, Pee Wee Gleason entered a protest in the final scoring, which affected positions eight through 20.

For some, it was a time to rest until morning. But others had an all-night job ahead replacing and rebuilding tired and broken parts. Early in the year, when the idea of the back-to-back Miles had been proposed, many felt it would be unfair to privateers who might have only one bike to ride. Indeed, two machines would be nice to have around in the event of serious trouble; but in the end most rode the same bike both days.

And the hot guys from Saturday night were the hot guys Sunday. Fast time of the day was turned in by Springsteen; the 37.812 sec./95.208 mph would have been good for sixth fastest the night before, but the daytime black groove is a bit slower.

A big surprise was Ken Roberts ticking off the second fastest time on Skip Aksland's Yamaha. "This thing's faster than my good bike was," Kenny was happy to announce.

Heats were taken by Springsteen, Roberts, Gary Scott and Mike Kidd, with Steve Droste and Jay Ridgeway winning the semis. Scott would have pole position for the National since his was the fastest heat race. Greg Sassaman also managed to get himself into the fracas for the daytime event, though disappointed that his factory H-D had coughed its magneto the night before.

The start was again a banzai charge for slots up front. Those closest to leader Kidd included Ted Boody, Springsteen, Gary Scott and Terry Poovey. Everything was sorting itself out nicely when, on the fourth lap, heading into Turn 1, Gary Scott tried to stuff Boody out of his way. It may be Boody's first Expert year, but he doesn't stuff very easily, as Scott soon found out. Down went Scott, into the haybales. It was obvious that Scott was not hurt —he popped right up and perched on a haybale—yet the red flag came out to stop the proceedings. The other riders were upset about the unusual decision, handed down by Mel Parkhurst sitting in the bleachers.

Starter Phil Dyson followed orders, but said he wouldn't have stopped it. Romero was even more disgusted when he saw that Scott's machine was barely scratched and would go back into the race. They even let him take it around a lap to check its condition. Roberts said to no one in particular, "They never stopped Syracuse last year with me out in the haybales and my bike all over the race track . . . did they?"

The race would be restarted single-file in the order that Lap 3 had ended. That put Scott dead last, but still in the hunt. Boody was showing off the dents in his exhaust pipes where Scott had made contact. One rider commented, "I don't know how Gary gets away with those things without getting hurt. One of these days it's going to catch up with him; I just hope he doesn't take anybody with him."

DOUBLE-HEADER RESULTS

Parkhurst explained later that he couldn't tell whether or not Gary was hurt, and rather than take a chance, stopped it. "Everybody always thinks you're showing favoritism if you do something like that and it involves the Number One rider. . . . You're damned if you do and you're damned if you don't." The reason was good, but the decision was poor. That's why there are turn marshals with radios to relay that kind of information; and that is also why the decision did, in fact, smack of favor itism.

Restarting went well, and the race once again turned into a Kidd/Springsteen af fair. There was no doubt, though, that Springer had received explicit instruc tions as to how to handle Kidd . . . and the rest of the gang, for that matter. The restart had helped Roberts tremendously because of a poor initial start. By Lap 15 he found himself knuckle to knuckle with the leading duo, made it a trio, and won the lap to show them he meant business.

rariner DacK, ary coti, too, was meaning business. In a fantastic riding display, he had worked his way up into the standings (and the National points) while closing on the leaders. Romero, running strong in 4th with a possible 3rd in the offing, suddenly found his H-D running on one cylinder and dropped back quickly. Later, he found that he'd shut off a fuel petcock when reaching down to tuck out of the wind on the straight.

Roberts had a chance of doing better than 3rd, but fell prey to another incredi ble example of his poor luck; his steel shoe broke in half! After the race he said, "Did you ever try to ride a Mile without a steel shoe? Impossible!"

Springsteen had left nothing to chance and stretched his lead enough to keep Kidd from catching a draft. The win was his third of the year and the fifth of his career; his two-day total of National points was 36. Scott and Roberts had managed 21 apiece, putting the threeway battle into a near deadlock, It just may go down to the last race of the year on the half-mile Ascot oval. In case of a tie in points, the rider with the most wins will get the Championship.

It was a superb radng weekend. No one was hurt, the events were hard fought, and the points battle got even tighter. Even the mechanics, few of whom got much in the way of sleep, are ready for another double-header next year. But what about the equipment?

I asked Springsteen's wrench, Bill Werner, what he would do to the V-Twin after so many hard miles of racing, good for a 1st and a 2nd and 36 National points. A complete rebuild . . . or what? "I'm gonna take it apart and love it," Bill replied, smiling.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

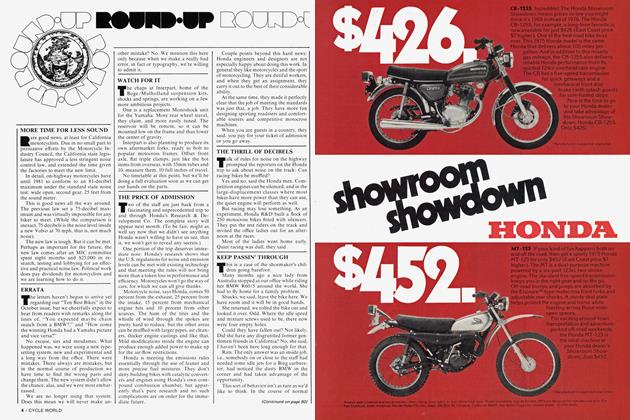

DepartmentsRound·up

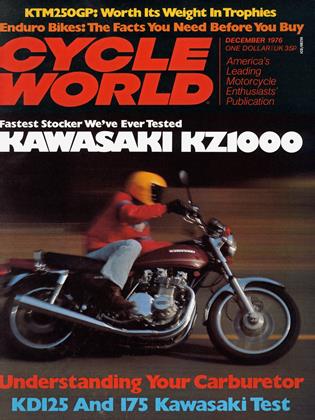

December 1976 -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1976 -

Demise of the British Industry, Ii

December 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

December 1976 -

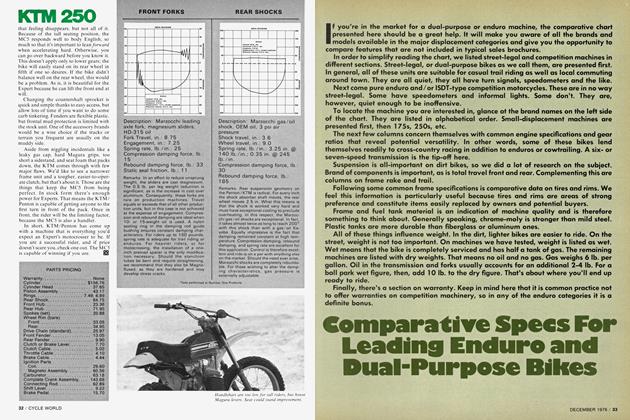

Technical

TechnicalComparative Specs For Leading Enduro And Dual-Purpose Bikes

December 1976 -

Features

FeaturesPro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

December 1976 By Russ Darnell