BERKSHIRE INTERNATIONAL TWO-DAY TRIAL

A Test Run That Proved U. S. Organizers Are Capable Of Hosting The International Six Days Trial.

John Waaser

WHAT'S THE MOST prestigeous motorcycle competition event in the world? It's not Daytona, with its big-buck road races; or Bonneville, where absolute speed records are set and broken; nor is it the Isle of Man, with the most demanding road race circuit in the world; or even the Motocross des Nations, where many countries vie for the title of World Motocross Champion. No, it is the International Six Days Trial, the only event on the FIM calendar which every single FIM member endeavors to attend.

So, how does the Berkshire two-day trial fit into this scheme of things? It was, quite simply, a required test to see if U.S. promoters are capable of running

such an important international contest as the ISDT.

Because the Berkshire Trial was a success, and because the U.S. will host the ISDT in ’73, let’s digress a moment and see how this all came about.

The Six Days traditionally has been hosted by the country which won it the previous year. Because of the prestige involved, many communist block countries have made their ISDT team a government effort, sparing no expense to win. In fact, East Germany won it five years in a row. So, the FIM adopted a resolution that no country could host the event more than twice in a 5-year period. Another recent resolution states that the winning nation will host the event on the second year following its win. A nation which wins and does not want to host the event may step down in favor of another nation.

Tiny Czechoslovakia won the event in 1970, earning the right to host it in 1972. They won again in 1971, earning the right to host it again in 1973. But, in view of the cost of holding such an event, and the stipulation that no winning nation may host it more than twice in five years, they elected to step down. The AMA had just been recognized by the FIM as the official governing body in the United States, and the AMA announced it would like to host the event in 1973. Czechoslovakia said it was fine by them, and the FIM congress awarded the event to the United States, in spite of the fact that we’ve never finished better than 4th.

Nominally, then, it’s the AMA who will be running the ISDT when it comes to America next year. But the AMA is a sanctioning body, not a promoter. In the entire United States, only one group has had any experience in organizing this type of event, and that is Intersport, promoter of the Berkshire Trial. So, the AMA turned to Intersport for assistance, and Massachusetts became the proposed site.

Intersport, however, had just held its three-day trial, and was in no mood to hold a test trial (required of first time host nations) for the FIM observers. When the AMA announced that the three-day preliminary event would be held in Massachusetts, a business associate of Intersport President Bob Hicks commented, “If there’s going to be another three-day trial in the Berkshires, AMA Public Relations Director Ed Youngblood is going to run it!” Intersport officials did, however, want to host the ISDT, so a deal was worked out with the FIM to hold a smaller, two-day event following the 1972 Six Days.

New England’s enduro sanctioning body is the New England Trail Riders Association. Since most Intersport officials also belong to NETRA, and since NETRA had a large quantity of volunteer workers available, Intersport decided to give NETRA the job of promoting the test event. So, a sanctioning body (NETRA) ran this all-important Berkshire which was awarded to another sanctioning body (the AMA).

In general, both AMA and FIM officials were impressed by NETRA and by AÍ Eames, the originator and organizer of the Berkshire event. Don Woods said of NETRA “I’ve never seen a group of more enthusiastic people.” And a Czechoslovakian observer, viewing the event with Intersport’s Dick Bettencourt, noted that most riders arrived at the checks five minutes before their due time, but that almost nobody arrived earlier than that. “This shows good planning,” he said.

Back to the event itself....

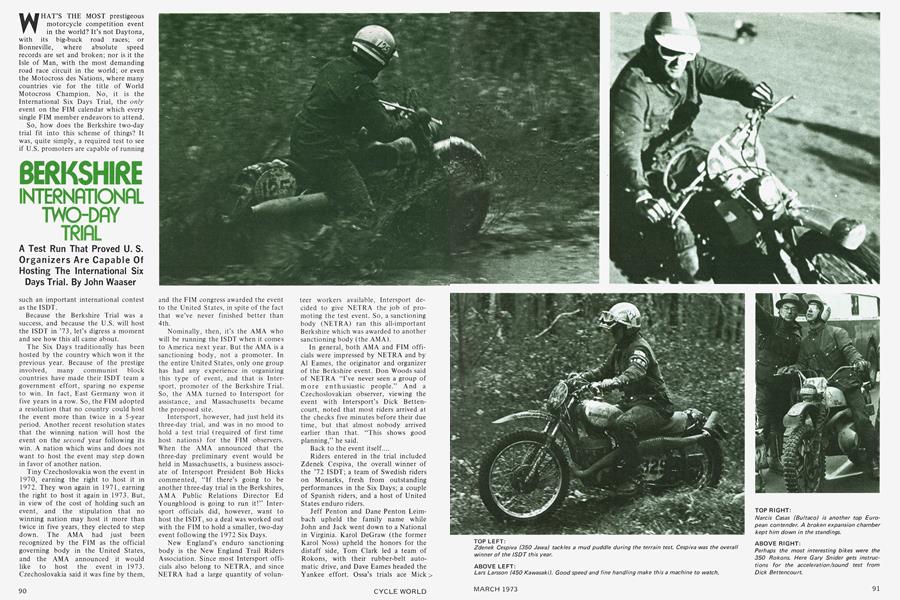

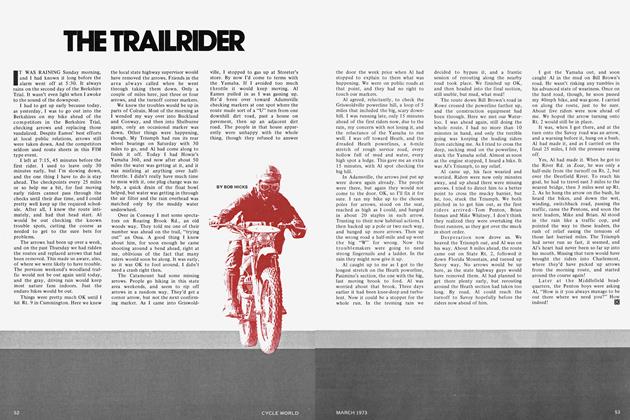

Riders entered in the trial included Zdenek Cespiva, the overall winner of the ’72 ISDT; a team of Swedish riders on Monarks, fresh from outstanding performances in the Six Days; a couple of Spanish riders, and a host of United States enduro riders.

Jeff Penton and Dane Penton Leimbach upheld the family name while John and Jack went down to a National in Virginia. Karol DeGraw (the former Karol Noss) upheld the honors for the distaff side, Tom Clark led a team of Rokons, with their rubber-belt automatic drive, and Dave Eames headed the Yankee effort. Ossa’s trials ace Mick Andrews was entered, but broke his collarbone while playing in Yankee prexy John Taylor’s backyard. Barry Higgens was assigned his spot, but didn’t arrive in time Monday morning, so Taylor himself took the slot.

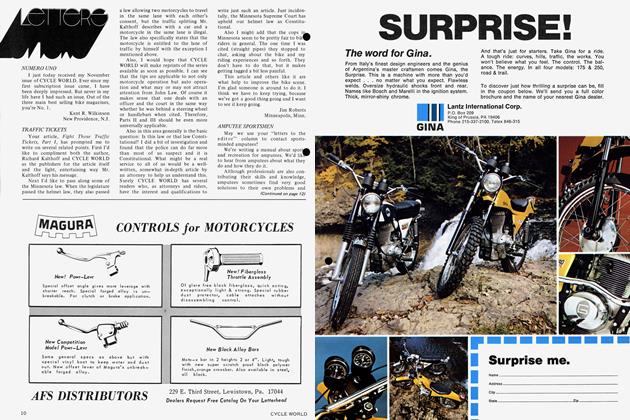

Unusual machinery included Cespiva’s 350cc Jawa, the Rokons, Dave Ekins overbored Bultaco Alpina in the open class, a team of 450cc Kawasakis, and the Monarks. The Russians had sort of been expected, and in fact it was rumored that they had been in the area most of the week scouting areas to put their support vans. But no, they were sorry, they would be unable to make it this year.

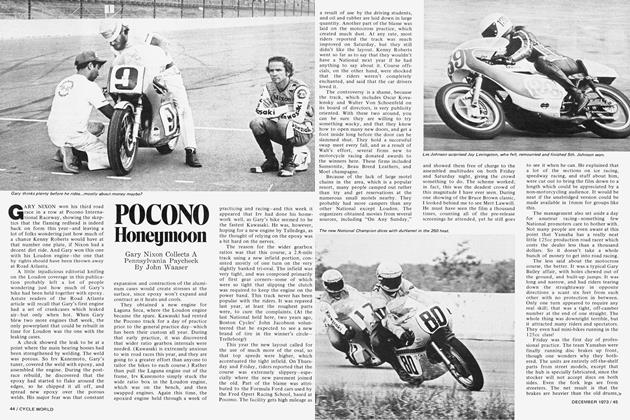

In spite of the efforts to use the easiest possible stretches of trail, Dave Eames found one section not to his liking—his father had included one stretch which Dave knew only too well: an old railroad bed, no longer in use, with many ties missing. This made each tie that you did hit a resounding jolt — quite a chore on the massive Yankee. And late Monday saw three tight stretches right together. They were so tight that even top riders commented that they didn’t have time to change a plug, or oil and adjust the rear chain. That, according to many, is actually too tight for the ISDT.

Four riders failed to make the start on Monday morning, and within a half hour after the start, Fred Chase, of San Francisco, had fractured his knee. Snow was falling in one area, and fog hung low in several spots. A water crossing used both days took riders over mosscovered, slippery rocks. In fact, the first half of the trail was the same on both days; they split only after the acceleration/sound test.

The sophisticated sound metering equipment which the AMA had promised never showed up, and Fred Mitchell filled in, using Intersport’s sound meter. This proved a tremendous advantage to the noisy bikes, as the measuring point was much farther away and higher up than the promised equipment would have been. Still, several bikes flunked, and a few riders were spotted doing everything in their power to lower the sound level. One of those who flunked was Spanish Bultaco rider Narcis Casas, whose expansion chamber had fractured. Some riders tried backing off but that isn’t the answer either, as acceleration test points are multiplied by five, to give a strong weighting to the results. He who backs off will lose more in acceleration than he gains in silence.

The strangest machines at the acceleration test were the Rokons—their engines never revved up, due to the continuously variable transmission. So they sounded slow. And their riders were crawling under the paint, as if on a top-speed run. This seemed ludicrous on an acceleration run, and made them look as slow as they sounded. Appearances, however, were deceiving; they were among the fastest-accelerating bikes entered.

Monday’s second special test was a terrain test, on the infamous October Mountain. As I was setting up some photo equipment, in a practically inaccessible spot, a marshall drove by. I would have expected him to stop, but perhaps he felt that nobody would service a rider in the middle of a special test.... A Hodaka rider came by, however, who would gladly have accepted help at that point. He had no first gear, and was stalling his bike every few feet.

One of the most impressive looking bikes on the terrain test, perhaps unexpectedly, was the Rokon. You might think that the inability to select a particular gear would be a disadvantage, but the rider just slogged through, popping the front end up at will, and generally having a ball.

One thing I noticed while walking back to my car, was that the almost 80 bikes which had gone through here in an all-out speed test had done virtually no damage to the soil. There was no wholesale erosion, and indeed, the tracks of the frontrunners had seemed as deep and as clear-cut as those at the end of the run.

A NETRA official reported 37 machines not impounded following Monday’s ride, but those of us there counted 56 or 57 machines actually in the impound area, which would mean that the total of dropouts was less than that. Seventeen riders were still zeroed. Only one team was still on gold, however, and that was the Swedish Monark team.

Monday night the jury was to meet, as it would every night during the Six Days Trial. The jury consists of one representative from each country entered, and was observed by Señor Juan Soler Bulto. Don Woods, as Clerk of Course, would also be there. Members of the press were excluded.

One of the points which Woods had to bring before the jury was the problem of figuring “evaluation points” for each retired rider. Evaluation points are computed from the special test points, by combining each rider’s total from the day’s two tests, then giving the lowest man in each class a zero, and substracting his test score from every other rider’s score to determine each rider’s evaluation point total. Riders who retired before the second special test would naturally have a lower special test score; yet their evaluation points could prove significant in breaking team ties.

Another problem concerned one acceleration test result, after a marshall drove through the timing light in the wrong direction, and shut the timer off early. In that case it was decided that the rider’s Tuesday score would count for both days.

Tuesday morning’s start took place in fog and light rain. Riders that day were on a faster time schedule, and hoped for good weather. Al Zitta, one of those riders still on gold, reportedly suffered transmission failure within a few feet of the start. Lew Mulligan had difficulty starting his Bultaco, which still hadn’t fired after the last numbers were flagged off. Reportedly he finally did get going, only to break a frame eight miles out. Narcis Casas had brazed the expansion chamber of his Bultaco, but still did not get a muffler on it.

Tom Clark arrived at the third check asking for chewing gum. “Give me all you’ve got. Unwrap it and put it in my mouth. Hurry.” I gave him almost a full pack of regular flavor Dentyne—even one stick of which tastes pretty strong. A checkpoint worker felt that perhaps Tom’s mouth had gone dry, and that he wanted the gum to get his saliva glands working. Later, however, we found the reason for his demand; his Rokon gas tank was leaking badly, and he was pressing gum on the seam in an effort to hold gas in the tank!

Late in the morning, the clouds and fog disappeared, and the weather turned clear and cold. At the sound test, the Czech rider Zdenek Cespiva retired with what was reported to be magneto failure. Those who were close to the Czech effort report that it was the same sort of magneto failure which used to plague the old Harleys at Daytona. “Yes, Andres suffered magneto failure—when the rod went through the cases, it tore up the windings something awful....” Later, another injury occurred when Ben Abel caught his foot in a wire, went down, and suffered a concussion, a few miles from the sound test.

The Yankee effort suffered misfortune twice on Tuesday afternoon; Dave Eames hit a tree, breaking his clutch lever, and John Taylor, due to a carburetor malfunction, ran out of petrol. Eames recovered from his little incident well enough so that, while he had used up all of his 3-min. grace period at the next check, he lost no points, and still finished in the overall winner slot.

Last on the agenda was the road race. Riders got one conducted lap first, following Don Woods in his rented Chevy. There would be three heats, of approximately 15 to 20 riders each, divided approximately according to engine size. Each heat would last four laps.

Kurt Gustavsson led a Monark sweep of the 125cc class. Monark rider Bengt Gustavsson dropped the plot in the tightest turn, but picked it up again so fast you’d have thought it was a ballet routine. As the 250s followed Woods on their conducted lap, he became more convinced of their suicidal intent; they followed him so closely that their tires were polishing the chrome on the Chevy’s bumper—and even though he lightly tapped the brakes before slowing down, to flash the brake lights, they didn’t back off until the Chevy slowed.

Carlos Giro, the Spanish Ossa rider, won the 250cc road race, ahead of Marcis Casas, and first American Don Cutler. Tom Clark did not take the conducted lap in the open class, but rested his leaking Rokon on its side to preserve fuel. As the others lined up, he pulled the starter cord (a la lawnmower), and tore off at the flag, to finish 3rd, behind Steve Hurd on the 450 Kawasaki, and Dave Eames on the Yankee Twin. The Berkshire Invitational was over. (Except for the final inspection. One Rokon had quit, and could not be restarted. Rokon people pulled the starter cord for 5 or 10 minutes, hoping to turn the engine fast enough to produce lights, but it was to no avail.)

Señor Juan Soler Bulto is going to report favorably to the FIM. He said that the only problems were small things caused by lack of familiarity with the rules.

So, unlike Colorado, and the Winter Olympics, “The Olympics of Motorcycling” looks like it’s coming to Massachusetts.

TWO-DAY RESULTS