Demise of the British Industry, II

Something about the British motorcycle creates emotion. Joe Scalzo’s “Demise of the British Industry" in Cycle World's September issue drew piles of mail, pro and con, from members of the motorcycle industry and from readers who own, used to own or plan to own a British bike.

A large response indicates lots of interest in the subject. For this reason we're devoting this special section to a sample of the reactions to the article.

From The Inside . . .

Congratulations to Joe Scalzo and Cycle World for writing and publishing the Triumph story. It’s fairly accurate and tells many of the Triumph happenings over the years, even though time and space did not permit mention of some of the main characters, the decision makers.

Johnson Motors, Inc., known over the years as “Jomo”, was founded by Wm. E. Johnson, Jr. in 1938 in Pasadena, California, and was one of the first major importers of motorcycles into the United States. Jomo became the national distributor for Triumph motorcycles in 1946. I was employed as a member of the Jomo staff in February, 1948, and remained with Triumph and the BSA group for 26 years (plus one day).

No history of Triumph or Johnson Motors would be complete without recognition of Wilbur Ceder, who was with the company from 1939 until his death in

1966. M.S. “Andy” Anderson is another deserving name. Andy joined Bill Johnson in 1938, and served as General Sales Manager (and subsequently as Parts Manager) until his retirement in 1970—over 32 years with Jomo.

Don J. Brown (now with Kawasaki) was another prime mover. Don worked with us for 14 years, first as Sales Manager and subsequently as Vice President of the group’s BSA Corporation in NJ. Scalzo credits Pat Owens with being Service Manager for 11 years. This must have been a typo, for 1 promoted Pat to the position of western Service Manager in

1967. He remained in that position till 1971, resigning to join the staff at L.A. Trade Technical College.

When the British factory opened the Triumph Corporation in Baltimore, MD., in 1951, Dennis McCormack was named as President of the eastern Triumph distributing company. Johnson Motors remained as the privately owned western distributor for Triumph and Ariel motorcycles in the 19 western states.

Certainly there was rivalry between east and west over the years. Triumph fans will remember that Jomo was an independently owned corporation, not dependent on factory money. While the eastern territory had 78% of the U.S. population (an equal amount of spendable dollars) the west sold about 40% of the U.S. motorcycles. In addition, we were in constant competition to sell more motorcycles; earn more profits and win more races. As long as this competitive spirit prevailed, both eastern and western companies prospered. In early 1965. Jomo was bought out by the factory; then Jomo bought the BSA distribution from Hap Alzina.

In 1965 I was transferred to Oakland, Ca., as Vice President/General Manager to create BSA Western, returning to Pasadena to take the helm of both Triumph and BSA in the west upon the death of Wilbur Ceder.

Sales for both brands continued to increase, as did profits through 1969. It may be sheer coincidence that the company’s fortunes started their downhill slide following the 1969 policy decision to blend the seven U.S. corporations into one giant company, named the Birmingham Small Arms Company Incorporated; with subsidiary companies named Triumph Motorcycle Corporation and BSA Motorcycle Corporation. Shortly thereafter, BSA Nutley was closed, and Baltimore then distributed Triumph and BSA. just as Duarte had been doing for four years. At any rate. 1969 was our last year as independent operators, and the end of our profits.

Scalzo’s assessment of Edward Turner’s racing policy was correct for England only, and the record books tell a different story for the American distributors. The east always sponsored their champions—like Gary Nixon, Ed Fisher, Buddy Elmore, Larry Palmgren and others. The legendary Nixon won Laconia and Daytona plus other championships. He won the Grand National Championship (and the # 1 plate) in 1967 and 1968. Other Baltimore riders did an outstanding job with the aid of eastern Triumph.

Johnson Motors first sponsored Bruce Pearson, on a well tuned 500cc Speed Twin, before the start of WW II. Pearson consistantly won TT’s and half mile events in southern California before many people were aware that Triumph existed. Being an ex-racer, tuner and corporate executive, I was privileged to head Jomo’s Triumph and Ariel racing activities from 1953 through 1969, and BSA’s efforts during 1965 through 1969. Starting with the 1970 season, I was assigned the task of directing all BSA and Triumph racing activités on a national level; an assignment that continued through 1970. 71, 72, 73 and the early part of 1974. During the early years. Jomo sponsored three successful world record attempts at Bonneville. Our riders. Johnny Allen, Jess Thomas (of Cycle Magazine) and Bill Johnson, all established new world speed records for motorcycles. The fastest speed was set with a streamlined Triumph Bonneville (650cc) by rider Bill Johnson at 232 mph. We also sponsored 100 or so other record runs at Bonneville. enabling Triumph to change their slogan to “The World’s Best (and fastest) Motorcycle”. Many of these old records remain unbroken.

For dirt track and TT racing. Jomo sponsored riders like Don Hawley, Chuck Basney, Jimmy Phillips, Bert Brundage and Joe Leonard.

Jomo sponsored other champions — Walt Fulton, Skip Van Leeuwen, Dick Hammer, Sid Payne, Eddi Mulder, Clark White and Dave Palmer (to name a few), and we worked very hard to develop a winning combination for the TT Bonneville that could be used by privateers. Triumphs are still dominating the TT’s in the Pacific Northwest, including the 1976 TT National at Castle Rock.

Triumph riders led by Bud Ekins swept the California desert events, week after week, just as Fulton, Ekins and others (don’t forget Don Hawley) took command of the Catalina Grand Prix for eight years.

In 1969, our U.S. President, Peter Thornton, asked me to develop a racing program that would win all the Grand National Championship events. He asked how much it would cost, and I presented him with a budget of $240.000.00 to sponsor two four-man teams; a team for Triumph with Gene Romero, Gary Nixon, Don Castro and Tom Rockwood, plus a team for BSA with Dick Mann, Jim Rice, David Aldana and Don Emde. In addition, I imported Mike Hailwood (BSA) and Paul Smart (Triumph) from England for the Daytona 200.

The rest is history. Gene Romero won the Grand National Championship (and the #1 plate for Triumph). The other team riders finished in positions 2. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. 9 and 12. After corporate headquarters added certain other promotional and public relations expense, the cost of the season increased to a staggering $400.000.00

In 1971, I was directed to reduce the budget, which forced me to cut the two teams down to two riders each. Our efforts did not go unrewarded, as Dick Mann captured the Number One plate for BSA, and our three other riders finished second, third and fourth. Not bad for a non-racing company.

Our 1972 and 1973 racing budgets were again slashed, and so were our racing victories. We put most of our money on Gary Scott, who did a super job by finishing the number two slot. To win races is great from a public relations viewpoint, but it’s a waste of money if you can’t back your wins with the right product, at the right price and at the right time. Our factories in England were promising some 50.000 motorcycles annually and good supplies of parts. Unfortunately we received only small quantities of both. Unfortunately again, our advertising campaign. racing and other expenses were geared to 40.000 sales and huge losses resulted.

Triumph could have remained healthy producing 25-30.000 units a year, if new models were made available and production schedules coincided with the U.S. market demands. But if you budget for 50,000 units as our group did, then receive less than 28,000 motorcycles, big losses occur.

Well, back to the main plot of the story. In England, Hubert (Bert) Hopwood was Edward Turner’s right hand man in the late 30’s and early 40’s, and had a great deal to do with the shape of things to come. Bert left the group to become Managing Director of Norton (pre Dennis Poore). Hopwood’s Nortons did win races but sales continued to slip, and Hopwood returned to BSA/Triumph. He was named Deputy Managing Director under Harry Sturgeon, and shortly thereafter headed the design and engineering side of the company.

Hopwood surrounded himself with a strong engineering team. Brian Jones was in charge of the design engineering department, and Doug Hele (the man who built the very fast racing triples) handled the development engineering and racing projects. The team did create some good designs on paper, plus a few prototypes—but the desperately needed capital was not available for the required tooling which would enable Triumph to bring out the new models. Among the unfinished models was a new Mark II Bonneville 750 and a 830 Triple. In addition, there were many other models still in various stages of design and development when the merger came.

Eric Turner (not to be confused with Edward) was Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer of the group of companies known as the Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited. Eric took over the chairmanship upon the retirement of Jack Sangster, and was the main decision maker until 1972. Immediately below Eric Turner in the BSA/Triumph motorcycle division was the office of Managing Director. Edward Turner (no relation to Eric) filled this position until retirement in 1962, followed by Harry Sturgeon; then Lionel Jofeh, who also resigned his position in 1972.

We made our proposals for new models to the board and Eric Turner (not Edward as reported by Scalzo). While Eric was generally in agreement the American proposals, at least one director put up road blocks, thus delaying models like the 750 Bonneville for four years or more.

I’ve probably overlooked a few important names of persons who played some role in the growth and ultimate fall of Triumph. Someday, perhaps, the whole story can be presented in book form.

Joe Scalzo ended his Triumph story by saying“. . . After 89 wearying years, Triumph’s name is still alive, however, barely. The question is, does anyone still care?”

I for one still care, and not only because I devoted 26 years to the Triumph effort. As they say in England, “Best of British luck—May Triumph Rise Again”.

E.W. (Pete) Coleman Balboa Island, Calif.

And The Outside . . .

After reading your article on the “Demise of the British Industry” I must commend you. It is one of the most complete and best written articles I’ve read in a long time.

Having owned nothing but Triumphs for 12 years, I found the article saddening. Triumphs, like Harleys, are in a class all their own.

What I’m saying is that as long as they make and sell Triumphs, I’ll own one. You can tell the people at Triumph for me that there are people who still care.

Jim Hine Williamsport, Penn.

I just read the article on the “Demise of the British Industry” and had to reply to you as an avid fan of the Triumph motorcycle line. I don’t have a bike yet but have great hopes of getting a Triumph 650cc as soon as possible.

If the Triumph-Norton line of bikes goes defunct, then many people who are (and are not but should be) involved with this company are going to get a lot of flack from people like me who know a good thing when they see it.

Patrick Guyot Troy, Mo.

Joe Scalzo’s, “Demise of the British Industry”, is not a bad shot at the whole sorry scenario—at least from your side of the Atlantic. But you are unfair when it comes to Meriden.

You omitted to mention that Dennis Poore’s plan to close Meriden was preceded by another plan—to cease production of all Triumph Twins. It is inaccurate to dub the Meriden work force as unionbacked men who cared nothing about motorcycles. If that were true, they would have taken their money and left. Instead they cared enough about their jobs and the future of Triumph to stick it out at considerable personal and financial hardship.

During the sit-in they cleaned and repainted the factory, reorganized production, designed and tested the rear disc brake and left side gear shift for the Bonneville and completed the export bikes locked inside. They didn’t get paid for this. If men like that are not motorcycle enthusiasts . . . what are they?

Suffice to say, I’m not a card carrying Communist and the last Triumph I owned was sold in 1967. No one in England is proud of the fall of our motorcycle industry. But inevitably we feel it is often misunderstood. Comparisons with Japan are spurious. For an example of what could have been—look at Italy.

Finally, BSA never stood for British Small Arms Company. It was the Birmingham Small Arms Co. Check the stacked rifles insignia on the timing cover of an old Single.

Ian Glover-James London, England

I have been involved with motorcycling for some time and have held the Norton in high regard for years. Now it appears that in trying to save Triumph, Norton has fallen and the workers co-op may survive. Norton plans a limited run in 1977 and then spare parts for—how long?

If Triumph lives and Norton dies I feel the lessor machine has won. To me the Norton motorcycle is the noblest of beasts, and finest of steeds and all that stuff. A young man I met at a coffee shop in Malibu Canyon one day summed it up pretty well in comparing my late model Commando to his beautifully restored Atlas, “When God created the Norton he had mountain roads in mind”.

Jim Cresap Manhattan Beach, CA

The article on the “Demise of the British Industry” was an excellent piece of journalism and an in-depth look at the hearsay and rumor that has been going around.

While my ’68 Trident patiently awaits restoration I ride my menace from Nippon, but I always will eye a shiny Bonneville and think unpure thoughts.

Jack D. Guske Puyallup, Wash.

What a pleasant coincidence. I just returned from a nine-week-cross-Europe tour on a 750 Triumph Bonneville and read your excellent article by Joe Scalzo, “Demise of the British Industry.” I have enjoyed your magazine for several years and felt compelled to reply to the last line of the article, “Does anyone still care about the Triumph?” Yes! I do!

I'm back home after nine weeks, 8000 miles and 17 countries. The trip was a total success. The bike ran perfectly the entire trip through days of heavy rain, extremely hot weather, bad mountain roads in Yugoslavia and the Autobahns in Germany.

I don’t know if the British bike industry will survive or not, but I know there will be one more happy Bonneville owner around for a long time.

Craig Bassett Vancouver, B.C., Canada

I quote from Sammy Miller’s book on trials. “As much as I miss the days of the Ariel, I feel one must advance with the times, or decay.”

Perhaps we should enlarge our outlook about the motorcycle industry. We wouldn’t even have bikes as good as the British made if it weren’t for the capitalistic system, to which they themselves fell victim. Products without consumer appeal will never keep a company alive, no matter how technically innovative they are.

Don’t be too quick to condemn fellow riders for not riding British machines. Remember that some of us prefer the quality of bikes like the BMW.

Dan O’Connell Wyckoff, N.J.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

December 1976 -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

December 1976 -

Technical

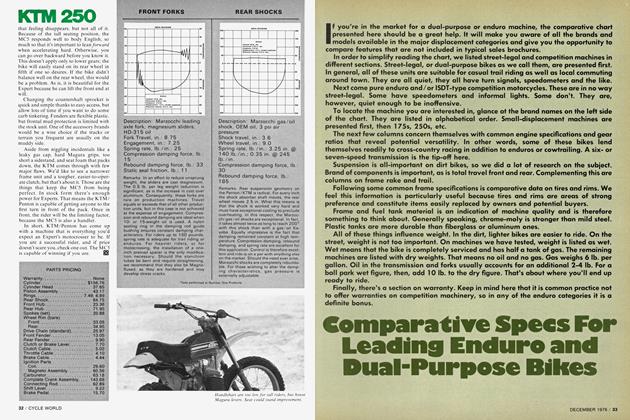

TechnicalComparative Specs For Leading Enduro And Dual-Purpose Bikes

December 1976 -

Features

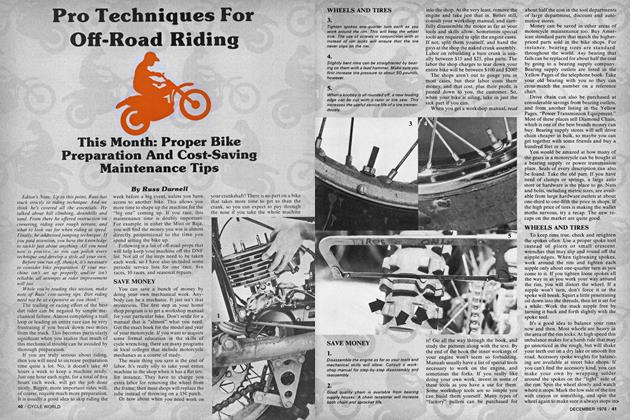

FeaturesPro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

December 1976 By Russ Darnell -

Competition

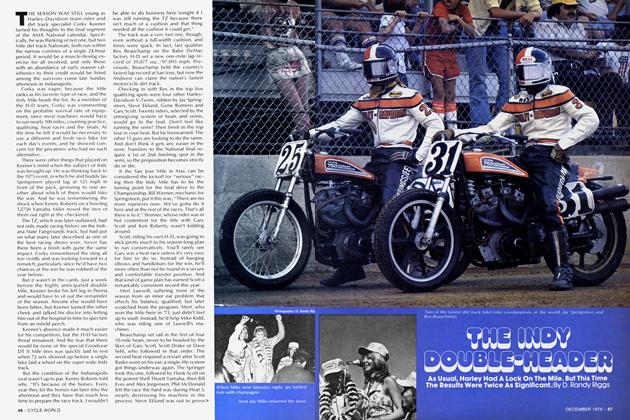

CompetitionThe Indy Double-Header

December 1976 By D. Randy Riggs