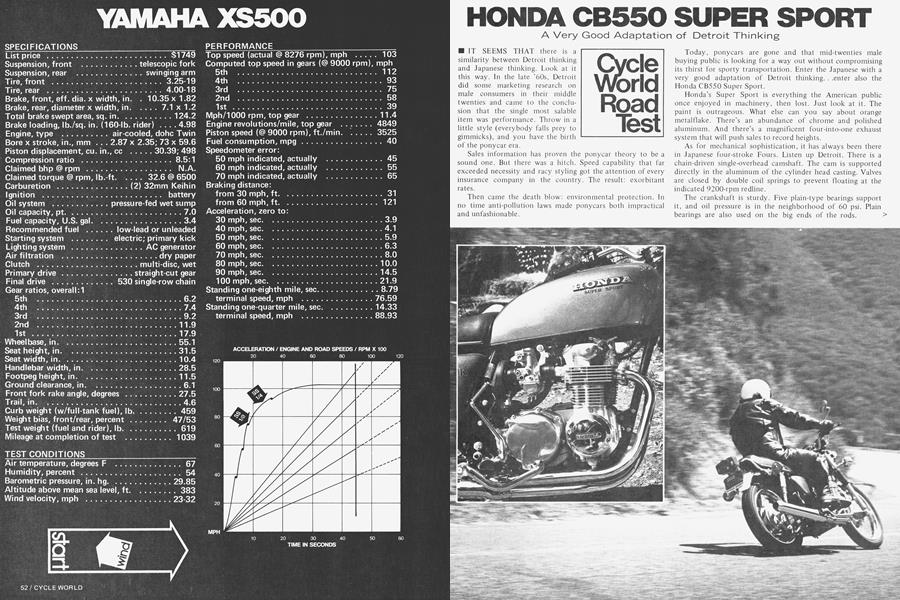

HONDA CB550 SUPER SPORT

Cycle World Road Test

A Very Good Adaptation of Detroit Thinking

■ IT SEEMS THAT there is a similarity between Detroit thinking and Japanese thinking. Look at it this way. In the late ’60s, Detroit did some marketing research on male consumers in their middle twenties and came to the conclusion that the single most salable item was performance. Throw in a little style (everybody falls prey to gimmicks), and you have the birth of the ponycar era.

Sales information has proven the ponycar theory to be a sound one. But there was a hitch. Speed capability that far exceeded necessity and racy styling got the attention of every insurance company in the country. The result: exorbitant rates.

Then came the death blow: environmental protection. In no time anti-pollution laws made ponycars both impractical and unfashionable.

Today, ponycars are gone and that mid-twenties male buying public is looking for a way out without compromising its thirst for sporty transportation. Enter the Japanese with a very good adaptation of Detroit thinking. . .enter also the Honda CB550 Super Sport.

Honda’s Super Sport is everything the American public once enjoyed in machinery, then lost. Just look at it. The paint is outrageous. What else can you say about orange metalflake. There’s an abundance of chrome and polished aluminum. And there’s a magnificent four-into-one exhaust system that will push sales to record heights.

As for mechanical sophistication, it has always been there in Japanese four-stroke Fours. Listen up Detroit. There is a chain-driven single-overhead camshaft. The cam is supported directly in the aluminum of the cylinder head casting. Valves are closed by double coil springs to prevent Boating at the indicated 9200-rpm redline.

The crankshaft is sturdy. Five plain-type bearings support it, and oil pressure is in the neighborhood of 60 psi. Plain bearings are also used on the big ends of the rods. >

The left end of the crankshaft supports the alternator rotor. Twin ignition contact breaker points are mounted on the right end. A simple spring-type automatic ignition advance is used, no doubt for its reliability.

A direct borrow from Detroit is the Morse Hy-Vol chain that transmits power from the crankshaft to the transmission. This chain uses tiny, rectangularly shaped teeth that are stacked tightly beside each other, resulting in almost silent running with high load-carrying capacity.

Multiple carburetors were big in the ponycar era and continue to be standard on Honda’s medium-displacement Four. Multiple in this case means four, and the size is 22mm.

Like we said, the Super Sport is everything the American public once enjoyed in machinery. The difference is that the Super Sport can cope with today’s problems, because it’s quiet, maneuverable, thrifty with fuel and easily insurable.

So, from a purely cosmetic or practical standpoint, the Super Sport is perfect. Honda, like Detroit, did its homework well. But can the Super Sport live up to its sporting reputation out on the highway? Is perfection only skin deep?

Now there’s an interesting question with a complicated answer, all depending upon the type of riding you have in mind. If you’re satisfied with blowing Datsun 240-Zs off in a straight line, and think 20 mph over the posted limit in turns is pushing your luck, the 550 is for you. If you demand more than that, the Super Sport may prove disappointing.

To clarify this, let’s consider the various situations a rider may encounter, from mundane to exciting, and evaluate the Honda’s performance in each.

Starting the Honda is easy when there’s sufficient juice in the battery. Just turn on the key, flip up the choke, and depress the starter button with your right thumb. It’s really idiot-proof because the 550 won’t start in gear unless the clutch is in. The reason we brought up the subject of the battery is this. Unless your dealer properly services the battery, chances are it will not hold a charge. We have found that a low battery just gets lower and will fail right when it is most needed. This is particularly common with the mandatory lights-on setup that was introduced by Honda. There is no switch to allow manual operation of the lights. We feel Honda should reinstall the switch and return control of this situation to the rider.

Warm-up is typically Honda. It takes three to five minutes before the engine will perform properly without balking when the throttle is applied. You can move off sooner, though, because the choke is adjustable, not one of those on/off numbers.

In spite of the engine’s lack of torque at low rpm, the machine will idle along through traffic without complaint. All the rider has to remember is that he cannot accelerate very quickly below 5000 rpm or so.

Handling around town is fantastic. There is no top-heavy feel at all, either in a straight line or when negotiating turns at a walking pace. Steering remains light at a crawl, as well. The Honda, in other words, handles traffic with ease. . .easier in fact than several so-called commuter bikes that have riders weaving all over their lane at sub-five-mph speed.

Automobile drivers will never know you’re there, at least from a noise standpoint. That four-into-one exhaust is unbelievably quiet. But unlike the GL1000, the rider can still hear the motor when downshifting.

Either in town, or out on the highway, the engine is smooth. Power builds with rpm, as with most Hondas, and at no point is there a sudden surge. As for vibration, it’s most noticeable between 50 and 60 mph. At that speed there’s a slight tingle in the bars. Go faster, or slower, and it disappears.

Sooner or later, every Super Sport rider is going to look for a country road. On straightaways he will be greeted by an eerie silence broken only by the wind rushing past his helmet. Turns at legal, posted limits can be taken without incident. Steering is light and control is excellent.

The ride at an easy pace is good. The Honda is unlike most Japanese roadsters in that it does not have oversprung front forks that jar the rider everytime there’s a crack in the pavement. The front suspension on the Super Sport soaks up bumps and it does so without the fault of excessive nosedive during braking.

Rear suspension at the same moderate pace is adequate, no more. Spring rate is light, yielding a soft ride. And that’s with a 150-pound rider and preload set in the middle position (springs are five-way adjustable). Two-hundred-pound riders will have to set preload to the maximum. Add a passenger and the bike will wallow down the road on considerably overloaded suspension. Heavier riders or those who carry passengers will have to purchase stiffer springs right off the bat.

Damping is nonexistent at the rear. At moderate speeds this doesn’t present much of a problem. In bumpy turns the machine will wallow slightly, and when passing at 80 or 85 mph, stability is affected, but not enough to cause alarm.

Start dicing with that Datsun 240-Z and you’ll win, but that will take you to the Super Sport’s limit. You’ll have an edge in acceleration, as the Honda gets it on pretty good. A quarter-mile can be covered in the high 13s or low 14s, depending on the machine, and top speed is around 100 mph.

Brakes are superb on the Honda. But even so it doesn’t stop as well as it should; our panic stops from 30 and 60 mph proved that. The problem—you just read about it—is lack of control at the rear shocks. As weight is transferred forward, the rear wheel has a tendency to hop wildly if the brake is applied with any force. Better suspension will mean better braking. Fade is minimal, and the front disc has good feel. When a corner comes up, you can still brake hard and pitch it in at 20 or 30 mph over the posted limit. This should allow you to leave that Z car in the dust, but if it doesn’t, don’t push much harder. You’ve reached the limit.

It isn’t a matter of ground clearance. Both the exhaust system and centerstand are tucked in pretty well. The frame is stiff enough. And it’s not tires. They’ve still got more in them too. It’s the rear shocks. Vary the throttle opening with the machine pitched over, and the bike will start wiggling. Hit a series of bumps and you’ll find yourself in a threatening wobble. Brake hard and the rear wheel will hop. Or encounter a crosswind on a bumpy straight at 8000 rpm in fifth and the bike wanders some.

PARTS PRICING

HONDA CB550 SUPER SPORT

$1830

It’s really too bad, because a set of Konis would make the Honda live up to its name. Mind you, they wouldn’t transform the Four into a racer, but they would restabilize the machine at 20 to 30 mph over the limit through the turns. And the bike would track straight at its top speed. We mention Konis here because the Honda shock uses a clevis lower mount and Koni has a replacement that bolts right on.

Even with the Konis, the Super Sport should not be thought of as a cafe racer. For one thing, better tires would enable the bike to be laid over far enough to drag the exhaust system and centerstand. On the left, the centerstand is easily modified for clearance, but not much can be done to the exhaust, except for grinding down the muffler clamp, which will not get you enough additional clearance to matter.

Then, there’s the matter of a cramped riding position if you try to tuck in. The tank is too short and the footpegs are too high and too far forward. Narrow bars would get you out of the wind but wouldn’t do a thing for the overcramping. And finally, when the engine gets warm, the gearshift shaft hangs up, making shifting difficult. Apparently there is insufficient tolerance somewhere, and when the engine heats up, binding occurs.

So, the Honda is perfect for the average rider and a more than fitting replacement for those who were into Z28 Cameros and GTOs. Or, it’s a cheaper alternative to the Z car. But for the occasional rider who will take the word Super Sport literally, problems will arise thanks to inadequate rear suspension. Super Sports are still nice, but don’t push too hard. [§]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue