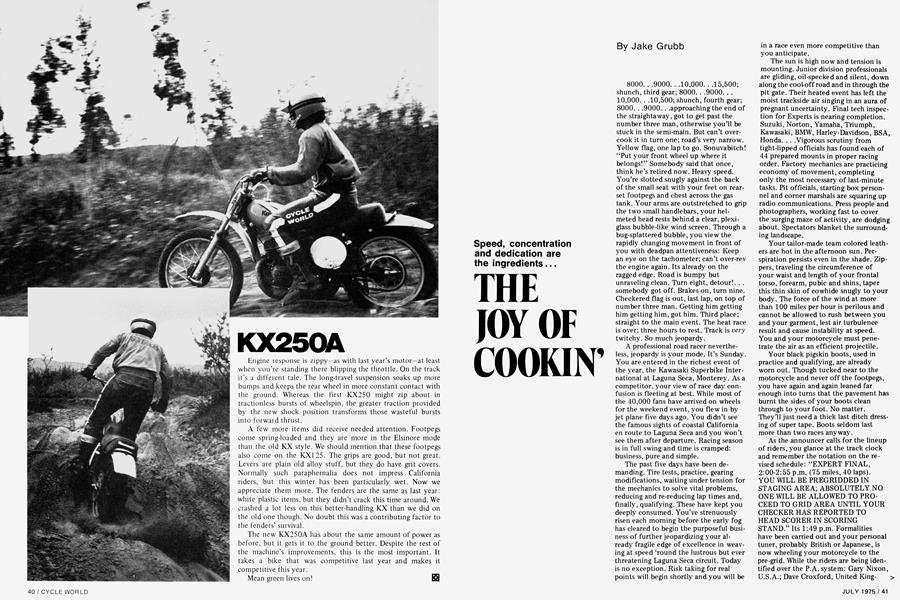

THE JOY OF COOKIN'

Speed, concentration and dedication are the ingredients...

Jake Grubb

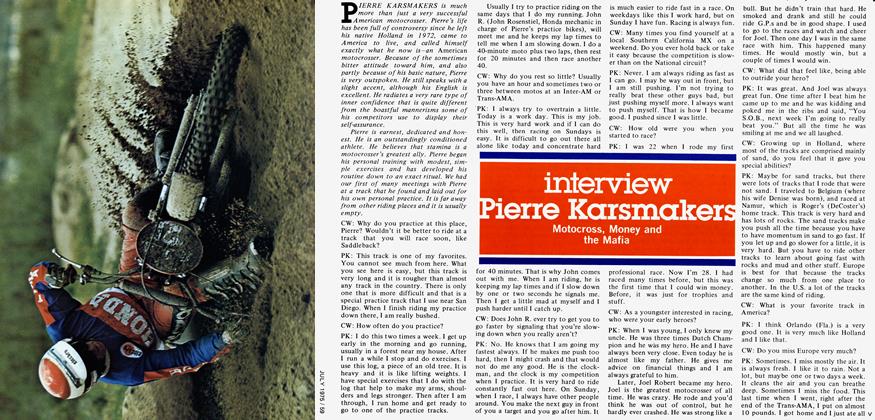

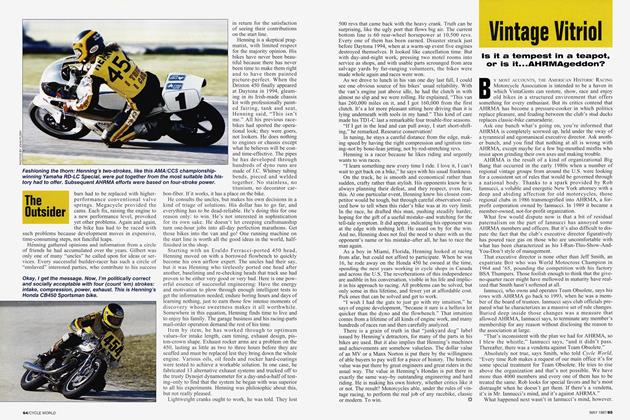

8000. . .9000. . .10,000. . .15,500; shunch, third gear; 8000. . .9000. . . 10,000. . .10,500; shunch, fourth gear; 8000. . .9000. . .approaching the end of the straightaway, got to get past the number three man, otherwise you’ll be stuck in the semi-main. But can’t over-cook it in turn one; road’s very narrow. Yellow flag, one lap to go. Sonuvabitch! “Put your front wheel up where it belongs!” Somebody said that once, think he’s retired now. Heavy speed. You’re slotted snugly against the back of the small seat with your feet on rear-set footpegs and chest across the gas tank. Your arms are outstretched to grip the two small handlebars, your helmeted head rests behind a clear, plexi-glass bubble-like wind screen. Through a bug-splattered bubble, you view the rapidly changing movement in front of you with deadpan attentiveness: Keep an eye on the tachometer; can’t over-rev the engine again. Its already on the ragged edge. Road is bumpy but unraveling clean. Turn eight, detour!. . . somebody got off. Brakes on, turn nine. Checkered flag is out, last lap, on top of number three man. Getting him getting him getting him, got him. Third place; straight to the main event. The heat race is over; three hours to rest. Track is very twitchy. So much jeopardy.

A professional road racer nevertheless, jeopardy is your mode. It’s Sunday. You are entered in the richest event of the year, the Kawasaki Superbike International at Laguna Seca, Monterey. As a competitor, your view of race day confusion is fleeting at best. While most of the 40,000 fans have arrived on wheels for the weekend event, you flew in by jet plane five days ago. You didn’t see the famous sights of coastal California en route to Laguna Seca and you won’t see them after departure. Racing season is in full swing and time is cramped: business, pure and simple.

The past five days have been demanding. Tire tests, practice, gearing modifications, waiting under tension for the mechanics to solve vital problems, reducing and re-reducing lap times and, finally, qualifying. These have kept you deeply consumed. You’ve strenuously risen each morning before the early fog has cleared to begin the purposeful business of further jeopardizing your already fragile edge of excellence in weaving at speed ‘round the lustrous but ever threatening Laguna Seca circuit. Today is no exception. Risk taking for real points will begin shortly and you will be in a race even more competitive than you anticipate.

The sun is high now and tension is mounting. Junior division professionals are gliding, oil-specked and silent, down along the cool-off road and in through the pit gate. Their heated event has left the moist trackside air singing in an aura of pregnant uncertainty. Final tech inspection for Experts is nearing completion. Suzuki, Norton, Yamaha, Triumph, Kawasaki, BMW, Harley-Davidson, BSA, Honda. . . .Vigorous scrutiny from tight-lipped officials has found each of 44 prepared mounts in proper racing order. Factory mechanics are practicing economy of movement, completing only the most necessary of last-minute tasks. Pit officials, starting box personnel and corner marshals are squaring up radio communications. Press people and photographers, working fast to cover the surging maze of activity, are dodging about. Spectators blanket the surrounding landscape.

Your tailor-made team colored leathers are hot in the afternoon sun. Perspiration persists even in the shade. Zippers, traveling the circumference of your waist and length of your frontal torso, forearm, pubic and shins, taper this thin skin of cowhide snugly to your body. The force of the wind at more than 100 miles per hour is perilous and cannot be allowed to rush between you and your garment, lest air turbulence result and cause instability at speed.

You and your motorcycle must penetrate the air as an efficient projectile.

Your black pigskin boots, used in practice and qualifying, are already worn out. Though tucked near to the motorcycle and never off the footpegs, you have again and again leaned far enough into turns that the pavement has burnt the sides of your boots clean through to your foot. No matter.

They’ll just need a thick last ditch dressing of super tape. Boots seldom last more than two races anyway.

As the announcer calls for the lineup of riders, you glance at the track clock and remember the notation on the revised schedule: “EXPERT FINAL, 2:00-2:55 p.m. (75 miles, 40 laps).

YOU WILL BE PREGRIDDED IN STAGING AREA; ABSOLUTELY NO ONE WILL BE ALLOWED TO PROCEED TO GRID AREA UNTIL YOUR CHECKER HAS REPORTED TO HEAD SCORER IN SCORING STAND.” Its 1:49 p.m. Formalities have been carried out and your personal tuner, probably British or Japanese, is now wheeling your motorcycle to the pre-grid. While the riders are being identified over the P.A. system: Gary Nixon, U.S.A.; Dave Croxford, United King> dom; Masahiro Wada, Japan; Marty Lunde, U.S.A.; Cliff Carr, United Kingdom. . . .thoughts of colleagues not present mingle briefly with the ceremony. Twenty-four year old New Zealand talent, Geoff Perry. Lost in a Transpacific air crash en route to the event. Brilliant World Champion Jarno Saarinen, killed recently in a high speed accident with Renzo Pasolini in the Grand Prix of Italy. Bustling, brighteyed Jarno. And Cal Rayborn.

1:54 p.m. Forty-four bullet-like bipeds are in staggered formation on the starting grid. Experts are filing to their mounts. You pull on your helmet and the familiar smell of the padding inside triggers a Pavlov response. Adrenalin begins to flow. A pat on the ass from your lissome lady sees you to row three, number four spot, where you straddle your cycle and methodically exercise your limb joints and arm muscles before folding them into riding position. 1:55 p.m. The five-minute sign appears on the starting bridge. All bikes are still facing backwards because they must be individually pushstarted and then turned around for frontward placement on the grid. One engine fires, then another, four more in unison, another, another, and another. . . .

Gloves on, feet on the pegs, pull in the clutch lever, hit second gear. Your tuner is pushing you now and you’re freewheeling. Drop the clutch, dddddd dddddddddddd dddddddZZZZZinggggg gggg! Your engine bursts to life and the ear-piercing testament of mind-bending horsepower brings on a peculiar comfort. The grid is now a sea of highrevving motorcycles and as you relocate your starting spot, the one-minute sign appears on the bridge. Onlookers are plugging their ears. Forty-four gifted motorcyclists are tensed and eyeing the man with the flag for the slightest telltale muscle twitch. Forty-four pairs of hands are subduing 44 screaming motorcycles and 44 hearts are pumping very, very hard. The one-minute sign turns sideways and the starter has the option. . . .All clutches depress as if computerized, 44 transmissions are jammed into first gear; the flag drops and the sound is unbearable.

For you, the ballet begins. As you rocket over the rise and the pack spreads out, you jostle for a position that will give you a clean shot through turn one. Your eyes can stop movement at one fifteenth of a second. That’s fast enough to see everything in one hell of a blur. All judgment becomes sensory.

You will shift 37 times a lap for just under an hour—more than 1400 shifts total if you finish the race, at an average of one gear change every two seconds. Your body will be numb from vibration and your left hand will be swollen stiff from depressing the clutch lever.

Approaching turn one from the extreme outside right, you brake ever so lightly, roll off on the throttle, bang back two gears and lean deep to the left. As you hit the apex of the curve, you ease the power on, shift up one gear and drift back out to the right side of the road where you skirt curbing briefly before leaning into a pock-surfaced turn two. You knock back two more shifts here, lean deep to the left again, exit with care not to get squirrelly and then accelerate down a one-eighth-mile straight section to turn three. Turn three is gone almost before you saw it coming, so hopefully you judged it well.

Your speed in mid-curve was a healthy 135 mph. You will negotiate six more turns before completing the fragile first lap, each of a different character and each with dizzying immediacy. After the rush under a bridge through an uphill turn four, you will jet away freely and sweep through turn five, only to sit straight up, break the wind, downshift furiously and lock brakes for turn six. While both tires are skipping and the gearbox is chattering, you will flick it into the downhill corkscrew where the bottom drops away like an elevator.

You will snake speedily around a long lefthand turn seven, trail down and to the right through an opposite-camber turn eight and then slow to a walking pace for the turn-nine hairpin.

Onto the pit straightaway you will accelerate with a blinding burst of horsepower, rear tire adrift on hard pavement, front wheel in the air. With your chest against the gas tank, butt pressed hard into the seat, you will accelerate through five speeds, hitting 10,000 rpm in each. Within six seconds from your exit from turn nine you will be traveling at top speed and be upon turn one again. Barring mishaps, incidentally, 43 other determined riders will still accompany you.

It is a rare cyclist who will ever win such a race. Given a genius for your craft, and the best possible motorcycle, you might win. But scores of variables defy even the most educated prediction. Each race is the most important race and the lst-place finisher is the only winner, with the exception of a few runner-up spots that bring lesser recognition and gate money. The winner gets the overwhelming best of praise, pampering, publicity, prize money and contingency funds. Those less than lucky go home tired, frustrated and penniless, but stronger for their efforts. Winner take all, literally, is the rule of the motorcycle Grand Prix.