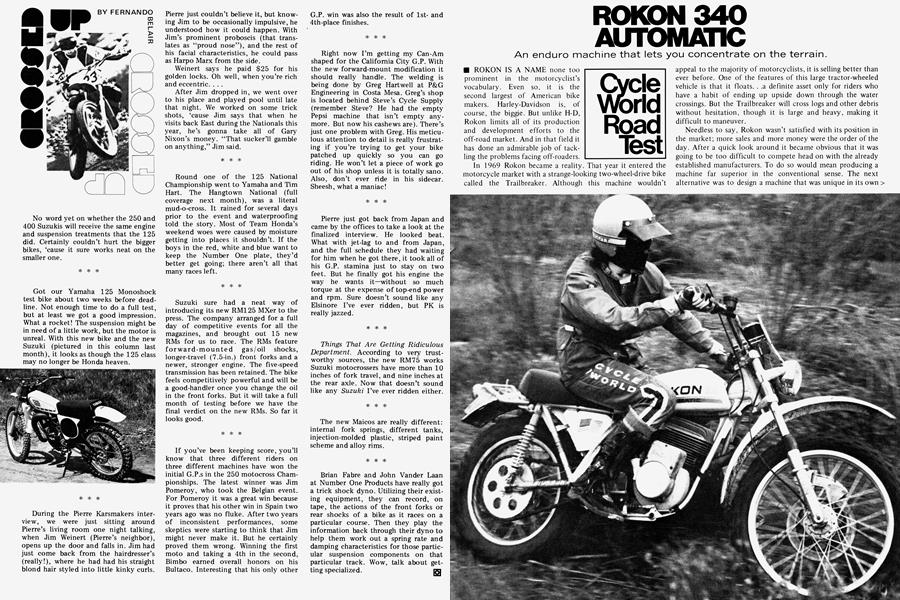

ROKON 340 AUTOMATIC

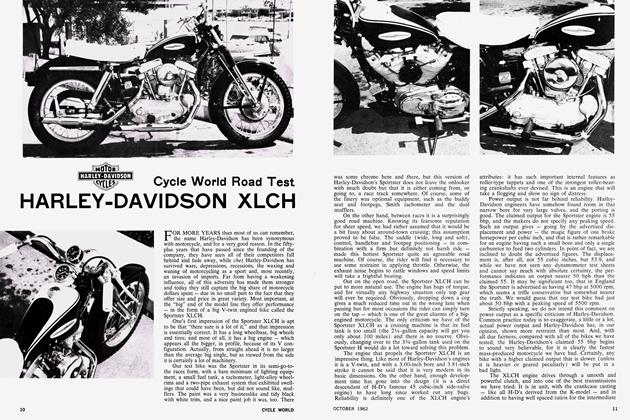

Cycle World Road Test

An enduro machine that lets you concentrate on the terrain.

ROKON IS A NAME none too prominent in the motorcyclist’s vocabulary. Even so, it is the second largest of American bike makers. Harley-Davidson is, of course, the biggie. But unlike H-D,

Rokon limits all of its production and development efforts to the off-road market. And in that field it has done an admirable job of tackling the problems facing off-roaders.

In 1969 Rokon became a reality. That year it entered the motorcycle market with a strange-looking two-wheel-drive bike called the Trailbreaker. Although this machine wouldn’t

appeal to the majority of motorcyclists, it is selling better than ever before. One of the features of this large tractor-wheeled vehicle is that it floats. . .a definite asset only for riders who have a habit of ending up upside down through the water crossings. But the Trailbreaker will cross logs and other debris without hesitation, though it is large and heavy, making it difficult to maneuver.

Needless to say, Rokon wasn’t satisfied with its position in the market; more sales and more money were the order of the day. After a quick look around it became obvious that it was going to be too difficult to compete head on with the already established manufacturers. To do so would mean producing a machine far superior in the conventional sense. The next alternative was to design a machine that was unique in its own right and also better than the competition. This innovative machine became a reality through the efforts of Mike Hamilton, design engineer, and Tom Clark, chief test rider and development engineer.

To meet the requirements of something new, unique and unusual, Rokon put a two-stroke snowmobile engine together with an “automatic” transmission and installed both of them into a well-constructed frame. Sounds trick, right? Well, it is. In two years of ISDT competition, Rokons have a 100 percent finish record; this in addition to 50 gold medals, 15 silver and 10 bronze. Not bad for a bike put together in the U.S.A.

This year’s test unit (the one Rokon is best known for), came to us in a crate from Keen, N.H., the company’s home base. Setup required only a few minutes. It involves attaching the handlebars and the panel for the route chart, speedo and watch holder. That’s all.

While assembling the RT, we noticed several changes-forthe-better over last year’s model. Take, for example, the wheels. Standard equipment was a set of Kirn-Tab magnesium alloy cast wheels. These worked well, but were expensive and heavier than their spoked counterparts. Now, Rokon uses Sun alloy rims. These are shoulderless and are designed with “tits” on the inside to prevent the tire from turning on the rim if it goes flat. There are no rim locks. Both Jack Penton and Carl Cranke use this type of rim.

The fiberglass tank has been replaced with a plastic unit that resists breaking and that is translucent in color, allowing fuel-level checking by sight. That sharp ridge on the first glass tanks no longer exists. Both front and rear fenders are now plastic and supplied by Preston Petty.

Usually, we try to take time and follow manufacturers’ recommendations for break-in on a new bike, but the Rokon was a different story. The RT was set up Friday evening and the Red Garter National Enduro was scheduled to run Sunday; TEAM CYCLE WORLD was entered. There were no other bikes in the garage capable of competing in this type of event, so after receiving the green light from Don Graves (now head of the company), we changed the oil in the speed reducer, put gas in the tank and readied ourselves for the event with a 1.6-mile break-in around the parking lot.

Well, we were almost ready. After the bike was standing on its own two wheels, we noticed that the rear shocks had only two inches of travel and no rebound. Not too good. At this late date there wasn’t much that could be done besides fitting a pair of Konis. However, they wouldn’t clear all of the rear-brake paraphernalia and were 0.5 in. too long. Contrary to all of the well-meaning advice we had received on mounting these upside down, we decided they would work and they did. The extra length didn’t slow us down either.

It appeared as though the springs on the standard Betors had sacked, preventing any rebound or travel, but this wasn’t the case. After checking springs and damper units, it was obvious that Betor had slipped everyone a ringer. Rokon specs call for 60/90-lb. springs; the ones fitted far exceeded this and were too stiff for all but the heaviest riders. The correct springs, which we received at a later date, are well-suited to the bike and our testers.

The Rokon company may be American, but the engine is made by Sachs, a West German concern. This 335cc, singlecylinder, two-stroke engine pumps out a claimed 37 SAE horsepower. A respectable figure for a bike this size. The Sachs engine is nothing more than a power plant, and has no means of transmitting power to the rear wheel by itself.

Rather than making use of a conventional four, five or six-speed gearbox, the Rokon transmits power through a variable-ratio torque converter that is driven off the left side of the crankshaft. This in itself throws most people for a loop, but it’s really quite simple. This is how it works. A fiber belt connects the front and rear pulleys. The crank pulley has sides that are angled and move in and out. As the speed of the engine increases, the outside portion of this pulley is forced in toward the engine. As this happens, the toothed belt rides higher on the ramps. This has the same effect as changing from a 12-tooth to a 13-tooth countershaft sprocket, and so on. At the pulleys the ratio is variable from 3.76:1 to 0.87:1. Overall, this figures out to a stump-pulling low of 27.0:1 and a high of 6.25:1.

Besides saving you from having to fish for the proper gear, there is another advantage to this “automatic” system. The torque converter transmits power to the ground smoothly; this, in addition to the shock-absorbing device at the rear pulley, almost negates any chance of unnecessary wheelspin in mud or other slippery conditions. All of this adds up to more power to the ground.

The shaft that supports the rear pulley runs through a device called a speed reducer. This provides an intermediate reduction ratio of 1.73:1. It incorporates a triplex chain that runs in a constant oil bath. The countershaft sprocket is driven directly off of the speed reducer. From here the power is transmitted to the rear wheel by a 530 single-row chain.

A large metal shroud covers the front and rear pulleys and the fiber drive belt. This shroud is no more than a guard against rocks and other large debris that might be encountered. The engine is wide at this point, making use of the cover advantageous against obstacles.

In no way do^ this cover work to keep out water and dirt. Water causes the belt to slip momentarily and there is some loss of power, but the belt dries quickly and everything returns to normal. Grit and grime are another story. They cause premature wear of the pulley. The belt is durable and will withstand almost anything thrown its way. Like tires, though, it is affected by many things, the most injurious factor being excessive heat.

Now we have the two major components for a selfpropelled, two-wheeled vehicle: a powerful engine and an “automatic” drive system. A third necessity is a frame capable of supporting these parts. Rokon’s frame is a tubular doublecradle type with a large-diameter top tube. To eliminate stress as the frame is assembled, MIG welding is used. This is a process whereby the welding rod is fed mechanically through the center of the welding arc. This produces a high and intense heat at a focal point, which precludes the necessity of heat treating the entire frame after assembly.

Attached to the front end of the frame is a pair of Betor forks. These have a claimed travel of 7 in., but we can only measure six. The frame is built to offer 28 degrees rake and 4 in. of trail with the Betor front end. The rake helps the bike to steer precisely, and the trail (which is greater than we like to see), gives it stability at speed. We feel as though the trail could be shortened somewhat, however, thereby improving low-speed response without affecting high-speed stability.

The RT was the first production bike to come with disc brakes all around. It is the only off-road machine with discs. Period. We like the idea of the discs because they aren’t bothered by water or mud, as are the conventional shoes. Initially, Rokon brake pads wore prematurely, but material changes have corrected this drawback.

Last year there was some concern over brake master cylinders. On our previous test bike we had the misfortune to experience a failure of the unit for the rear wheel. Under any conditions this can be critical, but in our case it was doubly bad. It happened, naturally, as we were going down the Matterhorn. Needless to say we had a few anxious moments. Luckily, bike and rider came out unscathed. This year we have not experienced a similar condition, nor have we heard reports of such incidents.

One braking drawback that hasn’t been corrected yet reveals itself when it becomes necessary to plant your right foot on the ground in a steep downhill section. Remember that below 2700 rpm the engine “freewheels;” there is no compression to help retard forward progress. When it becomes necessary to remove a foot from the peg, rear braking could be achieved by hooking up another lever on the bar and tapping into the rear brake cylinder. Such a modification may be standard on the ‘76 Rokons.

The overall effectiveness of the RT’s brakes is a far cry from the norm. The first time we applied the front stopper it almost pitched us on our head. The rear brake requires more pressure, but stops equally well. In short, the brakes rate a big A+ in our book.

During the course of the Red Garter, we had the throttle hang up several times and stick wide open once. At the time there was no chance to find out the cause, but upon subsequent inspection back in the CW garage, we found that the inner cable had started to unravel for no apparent reason. We built our own cable and had no further trouble. This is another time that the disc brakes proved invaluable.

So much for the pros and cons; how is it to ride? One word describes it all—fantastic! The bike roars to life with no more than three kicks. . .er, that is. . .pulls on the starter rope. Stand on the left side, take up the slack in the starter and give the rope one firm tug. The 36mm Mikuni carb does a fine job of mixing the fuel and air throughout the entire range. The manually-operated choke aids in cold starts. Remember to keep that front brake on while starting. On a motorcycle with an “automatic” transmission and no neutral position, the reason for this should be obvious.

If by accident the engine becomes flooded, there is a crankcase drain at the rear of the cases that can be opened. As the start rope is pulled, the fuel that has collected in the bottom end will be pumped out. This is a new feature on the ‘75 model.

After a few minutes of warmup the bike is ready to go. There’s no worry of stalling the engine when first gear is selected and the clutch plates aren’t broken free; there isn’t any clunk to the gearbox. Just gas it and away you go. At first, the absence of clutch and gearbox may be discomfiting, but not for long. The RT is so easy to ride. More time can now be spent concentrating on terrain rather than worrying whether the bike is in the right gear or slipping the clutch. The Rokon is always in the right gear.

After following the RT through a steep, muddy section, one of our staffers reported that the tire didn’t throw mud all over him, an indication that all of the engine’s power is being transmitted to the ground. This is a big help when accelerating out of a corner or negotiating slippery terrain.

It took us a short time to get used to the freewheel effect the RT possesses when going into a corner with the throttle off, but once we got a handle on it, it was easy. Just run in wide open and jump on the brakes as hard as possible, make the turn and gas it out. On the slower corners and sections the > throttle required judicious control; otherwise, the drive would couple up and pull the front wheel over backwards, leaving rider and bike deposited on the ground.

About the only thing we can point a finger at and say, “That should be better,” is the instrument panel. The VDO speedo and watch and route sheet holder are attached to an aluminum plate that is rubber-mounted. This keeps the speedo and a watch working, but makes them difficult to read. Perhaps a little stiffer mounting would help. There is a magnifying glass that covers both the watch and the route sheet. This is a nice touch, and a help in reading the chart, but we prefer a watch on our wrist.

After spending a lot of time and miles on the RT340, we can only say that it is a truly unique motorcycle. Rokon is on the right path with the drive system; it seems to be the thing of the future. And the company is continually improving the product through its MX and 1SDT efforts. Because Rokon isn’t building hundreds of thousands of bikes, like the Japanese, improvements and changes can be made at virtually any time. You, the consumer, benefit. |§1

ROKON 340 AUTOMATIC

$1645