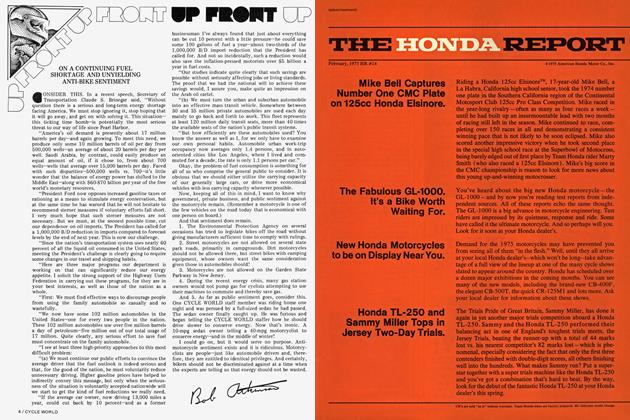

BOOK REVIEW

It is rather difficult to pin this book down in the naturally limited context of review. Picking representative passages to quote, as if to say, “This is what it is like,” would be akin to trying to photograph the Prairie: “You see it, and then you look down in the ground glass, and it’s just nothing. As soon as you put a border on it, it’s gone.”

To begin, though, the book is neither a religious tract nor a maintenance manual. The title functions as a bait, a clever mix of phrase to draw the reader along on a trip with the author and his son, a trip beginning in Minnesota, reaching a peak in the high country of Montana, and culminating on the Pacific shores.

The reader’s company on this journey (and, once begun, the trek cannot be easily terminated before its resolution), consists of the author, his son Chris, and a married couple, John and Sylvia, who on their BMW share the travel as far as Montana. At this point, having served to trigger the author toward his main themes, John and Sylvia leave, and their places are taken up by the gradual expansion of a character glimpsed already, who is to provide the meaning for the ride, and its terror. This character is Phaedrus, the ghost of the author’s past.

Pirsig himself describes Phaedrus in a passage made more brutal by its factual precision:

He was dead. Destroyed by order of the court, enforced by the transmission of high-voltage alternating current through the lobes of his brain. Approximately 800 mills of amperage at durations of 0.5 to 1.5 seconds had been applied on twenty-eight consecutive occasions, in a process known technologically as Annihilation ECS.’’ A whole personality had been liquidated without a trace in a technologically faultless act that had defined our relationship ever since. I have never met him. Never will.

And so the trip goes on, and with the travel, the maintenance of the motorcycle made necessary by miles. Using the upkeep of his machine as an example, Pirsig develops a philosophy, one that, along with the purely practical tips scattered through the book, will help the reader care for his own motorcycle; one that Pirsig hopes will help him to save himself.

(Continued on page 34)

Continued from page 30

Correct maintenance, the author says, depends upon “Quality.” This Quality is involved not only with the mechanic’s appreciation of what he is working with, but also with his ability to take time, and thus pride and care, in the work that he himself performs. Motorcycle maintenance, when done with Quality, becomes a phrase that performs in two directions: the

mechanic maintains the motorcycle, and, hopefully, the machine maintains the man. It is valuable, in a time when the common stereotypes show a normally reasonable man transformed by the power of cubic centimeters into a highway kamikaze, to have a presentation like Pirsig’s. The author, haunted by former madness, pressured by a son who seems to prefer the insane father that he has lost, presents the motorcycle, its riding and its care, as a soothing, calming and ultimately strengthening device.

As every motorcyclist who has undertaken a lengthy street tour, or competed in a grueling competition knows, the most painful actualities to deal with are not those involving inadequacy of machine, but the failures of the rider, of his own body or resolve. This knowledge is ever present in Pirsig’s work. The author, through meticulous maintenance, is able to avoid mechanical trouble, is able even to put some joy, some Quality, into the performance of the necessary tasks. These jobs both free and strengthen him for the job that is infinitely more painful, more frightening. This task is that which drives the reader down the highway, with father and son, at speed, sometimes joyously, but always with the washed-out bridge of personality known to mark the possible end of the highway.

Pirsig’s story is, above all, the chronicle of a search for union. The reconciliation of the author and his son, and of the author and his ghost-self, Phaedrus, are the primary goals of the quest. Another union, Pirsig tells us, must accompany these, however. When the classicist, the pure technologist, can share in the romantic sun-shouldered riding joy, and when the romanticist, the man concerned only with surface beauty, can share the classic storm-sheltered satisfaction of the right tool for the right part, then each man can live a bit fuller, fill his life with a bit more Quality. This union, above all else, is necessary for the solution of Pirsig’s dilemma, is the goal of Pirsig’s trip.

Bruce Woods

View Full Issue

View Full Issue