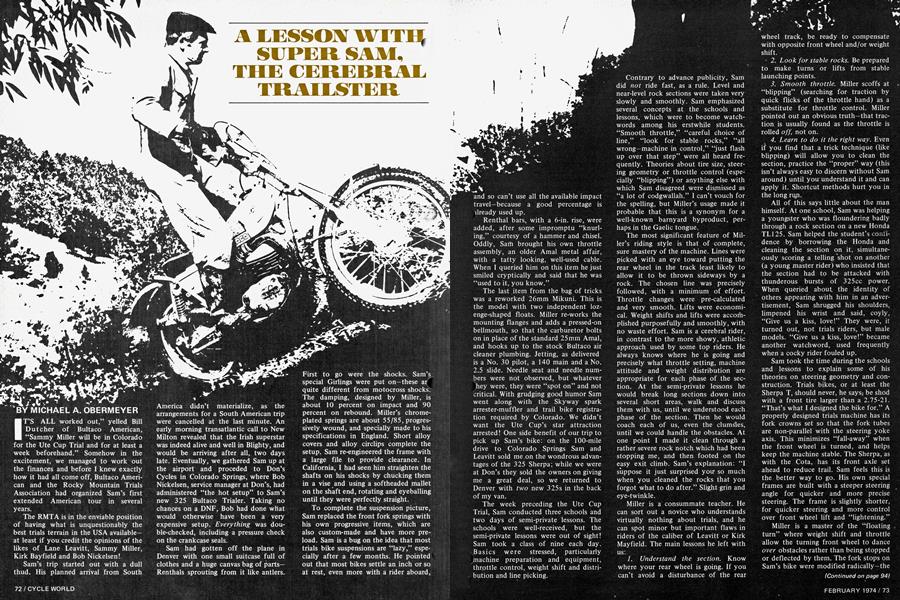

A LESSON WITH SUPER SAM, THE CEREBRAL TRAILSTER

MICHAEL A. OBERMEYER

IT’S ALL worked out,” yelled Bill Dutcher of Bultaco American, “Sammy Miller will be in Colorado for the Ute Cup Trial and for at least a week beforehand.” Somehow in the excitement, we managed to work out the finances and before I knew exactly how it had all come off, Bultaco American and the Rocky Mountain Trials Association had organized Sam’s first extended American tour in several years.

The RMTA is in the enviable position of having what is unquestionably the best trials terrain in the USA available— at least if you credit the opinions of the likes of Lane Leavitt, Sammy Miller, Kirk Bayfield and Bob Nickelsen!.

Sam’s trip started out with a dull thud. His planned arrival from South

America didn’t materialize, as the arrangements for a South American trip were cancelled at the last minute. An early morning transatlantic call to New Milton revealed that the Irish superstar was indeed alive and well in Blighty, and would be arriving after all, two days late. Eventually, we gathered Sam up at the airport and proceded to Don’s Cycles in Colorado Springs, where Bob Nickelsen, service manager at Don’s, had administered “the hot setup” to Sam’s new 325 Bultaco Trialer. Taking no chances on a DNF, Bob had done what would otherwise have been a very expensive setup. Everything was double-checked, including a pressure check on the crankcase seals.

Sam had gotten off the plane in Denver with one small suitcase full of clothes and a huge canvas bag of parts— Renthals sprouting from it like antlers.

First to go were the shocks. Sam’s special Girlings were put on—these ar quite different from motocross shocks. The damping, designed by Miller, is about 10 percent on impact and 90 percent on rebound. Miller’s chromeplated springs are about 55/85, progressively wound, and specially made to his specifications in England. Short alloy covers and alloy circlips complete the setup. Sam re-engineered the frame with a large file to provide clearance. In California, I had seen him straighten the shafts on his shocks by chucking them in a vise and using a softheaded mallet on the shaft end, rotating and eyeballing until they were perfectly straight.

To complete the suspension picture, Sam replaced the front fork springs with his own progressive items, which are also custom-made and have more preload. Sam is a bug on the idea that most trials bike suspensions are “lazy,” especially after a few months. He pointed out that most bikes settle an inch or so at rest, even more with a rider aboard, and so can’t use all the available impact travel—because a good percentage is already used up.

Renthal bars, with a 6-in. rise, were added, after some impromptu “knurling,” courtesy of a hammer and chisel. Oddly, Sam brought his own throttle assembly, an older Amal metal affair, with a tatty looking, well-used cable. When I queried him on this item he just smiled cryptically and said that he was “used to it, you know.”

The last item from the bag of tricks was a reworked 26mm Mikuni. This is the model with two independent lozenge-shaped floats. Miller re-works the mounting flanges and adds a pressed-on bellmouth, so that the carburetor bolts on in place of the standard 25mm Amal, and hooks up to the stock Bultaco air cleaner plumbing. Jetting, as delivered is a No. 30 pilot, a 140 main and a No. 2.5 slide. Needle seat and needle numbers were not observed, but whatever hey were, they were “spot on” and not critical. With grudging good humor Sam went along with the Skyway spark arrester-muffler and trail bike registration required by Colorado. We didn’t want the Ute Cup’s star attraction arrested! One side benefit of our trip to pick up Sam’s bike: on the 100-mile drive to Colorado Springs Sam and Leavitt sold me on the wondrous advantages of the 325 Sherpa; while we were at Don’s they sold the owners on giving me a great deal, so we returned to Denver with two new 325s in the back of my van.

The week preceding the Ute Cup Trial, Sam conducted three schools and two days of semi-private lessons. The schools were well-received, but the semi-private lessons were out of sight! Sam took a class of nine each day. Basics were stressed, particularly machine preparation and equipment, throttle control, weight shift and distribution and line picking.

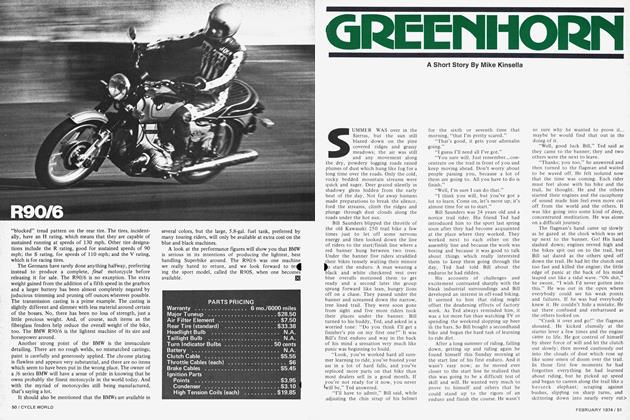

Contrary to advance publicity, Sam did not ride fast, as a rule. Level and near-level rock sections were taken very slowly and smoothly. Sam emphasized several concepts at the schools and lessons, which were to become watchwords among his erstwhile students. “Smooth throttle,” “careful choice of line,” “look for stable rocks,” “all wrong—machine in control,” “just flash up over that step” were all heard frequently. Theories about tire size, steering geometry or throttle control (especially “blipping”) or anything else with which Sam disagreed were dismissed as “a lot of codgwallah.” I can’t vouch for the spelling, but Miller’s usage made it probable that this is a synonym for a well-known barnyard byproduct, perhaps in the Gaelic tongue.

The most significant feature of Miller’s riding style is that of complete, sure mastery of the machine. Lines were picked with an eye toward putting the rear wheel in the track least likely to allow it to be thrown sideways by a rock. The chosen line was precisely followed, with a minimum of effort. Throttle changes were pre-calculated and very smooth. Lifts were economical. Weight shifts and lifts were accomplished purposefully and smoothly, with no waste effort. Sam is a cerebral rider, in contrast to the more showy, athletic approach used by some top riders. He always knows where he is going and precisely what throttle setting, machine attitude and weight distribution are appropriate for each phase of the section. At the semi-private lessons he would break long sections down into several short areas, walk and discuss them with us, until we understood each phase of the section. Then he would coach each of us, even the clumsles, until we could handle the obstacles. At one point I made it clean through a rather severe rock notch which had been stopping me, and then footed on the easy exit climb. Sam’s explanation: “I suppose it just surprised you5 so much when you cleaned the rocks that you forgot what to do after.” Slight grin and eye-twinkle.

Miller is a consummate teacher. He can sort out a novice who understands virtually nothing about trials, and he can spot minor but important flaws in riders of the caliber of Leavitt or Kirk Mayfield. The main lessons he left with us:

1. Understand the section. Know where your rear wheel is going. If you can’t avoid a disturbance of the rear

wheel track, be ready to compensate with opposite front wheel and/or weight shift.

« 2. Look for stable rocks. Be prepared to make turns or lifts from stable launching points.

3. Smooth throttle. Miller scoffs at » “blipping” (searching for traction by quick flicks of the throttle hand) as a substitute for throttle control. Miller pointed out an obvious truth—that traction is usually found as the throttle is rolled off not on.

4. Learn to do it the right way. Even if you find that a trick technique (like blipping) will allow you to clean the section, practice the “proper” way (this isn’t always easy to discern without Sam around) until you understand it and can apply it. Shortcut methods hurt you in the long rqn.

All of this says little about the man himself. At one school, Sam was helping a youngster who was floundering badly through a rock section on a new Honda TL125. Sam helped the student’s confidence by borrowing the Honda and cleaning the section on it, simultaneously scoring a telling shot on another (a young master rider) who insisted that the section had to be attacked with thunderous bursts of 325cc power. When queried about the identity of others appearing with him in an advertisement, Sam shrugged his shoulders, limpened his wrist and said, coyly, “Give us a kiss, love!” They were, it turned out, not trials riders, but male models. “Give us a kiss, love!” became another watchword, used frequently when a cocky rider fouled up.

Sam took the time during the schools and lessons to explain some of his theories on steering geometry and construction. Trials bikes, or at least the Sherpa T, should never, he says^ be shod with a front tire larger than a 2.75-21. “That’s what I designed the bike for.” A properly designed trials machine has its fork crowns set so that the fork tubes are non-parallel with the steering yoke axis. This minimizes “fall-away” when the front wheel is turned, and helps keep the machine stable. The Sherpa, as with the Cota, has its front axle set ahead to reduce trail. Sam feels this is the better way to go. His own special frames are built with a steeper steering angle for quicker and more precise steering. The frame is slightly shorter, for quicker steering and more control over front wheel lift and “lightening.”

Miller is a master of the “floating turn” where weight shift and throttle allow the turning front wheel to dance over obstacles rather than being stopped or deflected by them. The fork stops on Sam’s bike were modified radically—the

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 73 nylon buttons were stripped off and a good 1/8 to 3/16 in. was hacksawed off. Fork lock then approached 180 degrees. Coupling this with his exquisite throttle control and peculiar (to the uninitiated) weight shifts (see accompanying photos) Miller is capable of making astonishingly tight turns. Sam made turns with ease which defeated all but a very few of the best U.S. Masters. Sam set several sections with “hurpin” turns, which he insisted we practice. It took me half an hour to work up the courage to ask him what “hurpin” meant. “Hurpins,” it turns out, used to be worn by your mother, and were called hairpins.

Although the Ute Cup Trial was reported here in the December ’73 issue, I’d like to mention some competitors’eye-view observations.

Reportage of a traveling, timed event such as the Ute Cup is difficult, especially when you are attempting to compete at the same time. Watching the one-sided war of nerves between Whaley and Miller was most interesting, however. Sam has the knack, born of years of world-class competition, of knowing which sections are going to take points from even the best riders. On these

sections he would walk and re-walk the section, watching the less skillful dab, fall and fiasco. Whaley would watch Miller out of the corner of his eye, his concentration somewhat less complete than the Maestro’s. Finally Whaley would make an abrupt decision, mount his beautifully prepared Cota, and ride the section, usually taking a clean or at most a one. Miller would ride soon thereafter, almost invariably taking a clean. Marland’s rides were characterized by elan and aggressive riding, while Miller’s were smooth, controlled and effortless. Marland was obviously all too conscious of Miller, while it never became apparent that Sam even knew Marland existed.

Having gotten to know Sam rather well in a week of chauffeuring him around the state, I really don’t feel that there was any conscious effort on his part to “do a number” on Whaley; rather, the suggestion was more that of a journeyman bent on doing a workmanlike job at a craft he knows too well to worry about the efforts of competitors. Sam’s face never lost its quiet smile, and tension never showed.

During the two-day event, Sam steadily ate up the competition by his controlled, effortless rides. His style is much different from that of the young American Masters. His throttle control

is unbelievable—very smooth and wellplanned, with small increments, carefully delivered. In contrast, the younger riders seem to use hundreds of “bliij|^ in each section. Miller characterizes though not unkindly, as a substitute for throttle control. Leavitt, who unabashedly admits to having modeled his riding style after Sam’s, is a notable exception. His throttle hand and body movements are much more like the controlled, super-smooth style of his mentor. At section after section I would ask the checker “What did Miller do on this one?” The answer was usually “He cleaned it ” and I’d ask “But how did he do it?” and the checker would reply “I dunno—he just rode around it kind of easy....” This more or less characterizes Sam’s complete domination of the Ute Cup for 1973. In an event that took well over 100 points from most of the finishers, riding against the best that America has to offer, and “giving away 20 years to most of the blokes,” Super Sam just rode around it kind of eas}^ took his 16 points and the Ute Cup, a™ went home.

As for me, I’ll remember a head-tohead competition between Sam, Leavitt and myself much better than the Ute Cup. I damn near beat them both...and blew it with a three putt on the 18th hole. lo]