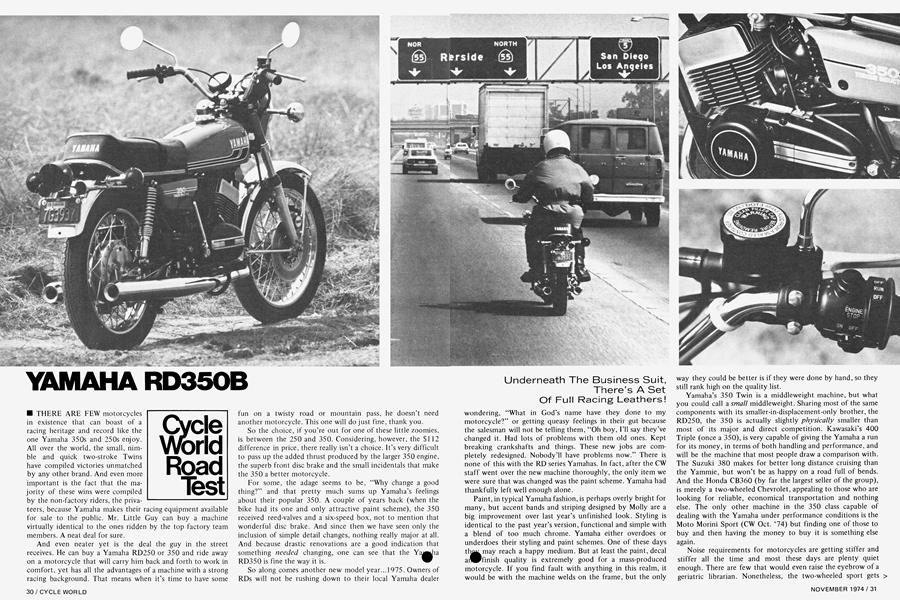

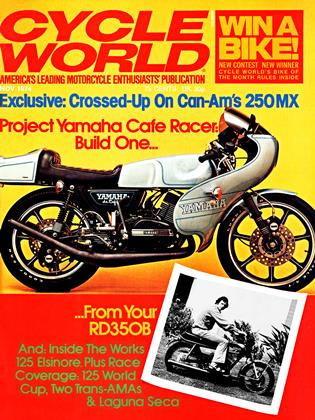

YAMAHA RD350B

Cycle World Road Test

THERE ARE FEW motorcycles in existence that can boast of a racing heritage and record like the one Yamaha 350s and 250s enjoy.

All over the world, the small, nimble and quick two-stroke Twins have compiled victories unmatched by any other brand. And even more important is the fact that the majority of these wins were compiled by the non-factory riders, the privateers, because Yamaha makes their racing equipment available for sale to the public. Mr. Little Guy can buy a machine virtually identical to the ones ridden by the top factory team members. A neat deal for sure.

And even neater yet is the deal the guy in the street receives. He can buy a Yamaha RD250 or 350 and ride away on a motorcycle that will carry him back and forth to work in comfort, yet has all the advantages of a machine with a strong racing background. That means when it’s time to have some

fun on a twisty road or mountain pass, he doesn’t need another motorcycle. This one will do just fine, thank you.

So the choice, if you’re out for one of these little zoomies, is between the 250 and 350. Considering, however, the $112 difference in price, there really isn’t a choice. It’s very difficult to pass up the added thrust produced by the larger 350 engine, the superb front disc brake and the small incidentals that make the 350 a better motorcycle.

For some, the adage seems to be, “Why change a good thing?” and that pretty much sums up Yamaha’s feelings about their popular 350. A couple of years back (when the bike had its one and only attractive paint scheme), the 350 received reed-valves and a six-speed box, not to mention that wonderful disc brake. And since then we have seen only the inclusion of simple detail changes, nothing really major at all. And because drastic renovations are a good indication that something needed changing, one can see that the Yaj*dia RD350 is fine the way it is.

So along comes another new model year... 1975. Owners of RDs will not be rushing down to their local Yamaha dealer wondering, “What in God’s name have they done to my motorcycle?” or getting queasy feelings in their gut because the salesman will not be telling them, “Oh boy, I’ll say they’ve changed it. Had lots of problems with them old ones. Kept breaking crankshafts and things. These new jobs are completely redesigned. Nobody’ll have problems now.” There is none of this with the RD series Yamahas. In fact, after the CW staff went over the new machine thoroughly, the only item we were sure that was changed was the paint scheme. Yamaha had thankfully left well enough alone.

Underneath The Business Suit, There’s A Set Of Full Racing Leathers!

Paint, in typical Yamaha fashion, is perhaps overly bright for many, but accent bands and striping designed by Molly are a big improvement over last year’s unfinished look. Styling is identical to the past year’s version, functional and simple with a blend of too much chrome. Yamaha either overdoes or underdoes their styling and paint schemes. One of these days tlmmay reach a happy medium. But at least the paint, decal ait^finish quality is extremely good for a mass-produced motorcycle. If you find fault with anything in this realm, it would be with the machine welds on the frame, but the only way they could be better is if they were done by hand, so they still rank high on the quality list.

Yamaha’s 350 Twin is a middleweight machine, but what you could call a small middleweight. Sharing most of the same components with its smaller-in-displacement-only brother, the RD250, the 350 is actually slightly physically smaller than most of its major and direct competition. Kawasaki’s 400 Triple (once a 350), is very capable of giving the Yamaha a run for its money, in terms of both handling and performance, and will be the machine that most people draw a comparison with. The Suzuki 380 makes for better long distance cruising than the Yammie, but won’t be as happy on a road full of bends. And the Honda CB360 (by far the largest seller of the group), is merely a two-wheeled Chevrolet, appealing to those who are looking for reliable, economical transportation and nothing else. The only other machine in the 350 class capable of dealing with the Yamaha under performance conditions is the Moto Morini Sport (CW Oct. ‘74) but finding one of those to buy and then having the money to buy it is something else again.

Noise requirements for motorcycles are getting stiffer and stiffer all the time and most these days are plenty quiet enough. There are few that would even raise the eyebrow of a geriatric librarian. Nonetheless, the two-wheeled sport gets hammered at (funny how the noisiest wheeled vehicles around, large trucks, get ignored), and bikes like the RD350 suffer, intake tract revisions have taken the sharp edge off the drag strip times of the still-rapid 350 in an effort to whack off a bit of drone when the twin 28mm Mikunis start gulping air. Most of that hurt came in ‘74. No further changes were made to the induction system for 1975, or else we might have seen yet another reduction in the neck snapping qualities of the 350. As it stands, Yamaha has a fairly quiet motorcycle here, and one that still performs.

As we said, the Yamaha RD is a physically small-sized motorcycle. The rider feels as though he is sitting well on top of the machine, rather than down in it and part of it. Something feels amiss until a ride is taken, and all of a sudden things begin to fall into place. The RD350 responds instantly, almost too quickly for those who are used to a more mundane machine, and the rider and motorcycle truly are one. The Yamaha is narrow, low and short-coupled in a way that says the rider is in control. And he is if he is prepared for a trait that a powerful, short-wheelbase, lightweight bike has: the tendency to lift the front wheel under hard acceleration.

The yo-yo who climbs on an RD350, revs the engine up and dumps the clutch, will be on his back so fast it will make his head spin. Likewise, too much throttle when accelerating out of a lower gear corner can do the same. But this is not going to happen to a rider with experience, or to one who coordinates throttle with brain. In the hands of the right rider, the Yamaha can run off and hide from the big bruisers on their 750s and 900s. Yet, it is still not picture perfect.

Frame wise, the RD’s chassis is very close to those used on the small bore Yamaha road racers. It is responsive to the nth degree, steers precisely but on the quick side, and suspension is taut enough to match the abilities of most riders. Swinging arm flex will only bother those riding on the ragged edge of staying upright and disaster, particularly if stock tires are in place. Once again, only mean, fast corners will show suspension flaws (too soft for the quickest riders) and some ii^nr wallow will occur. Compared to the majority of motorcycles, ground clearance on both sides of the Yamaha is more than generous; contacting the pavement with the footpegs is a good indication that the stock tires are ready to sign off anyway, so that’s a good time to roll back the throttle.

Small-bore production class racing is virtually dominated by Yamaha RD350s, and many show up, number plates intact, with very few modifications. Solid testimony to the fact that the RDs are one of the top-handling, best-performing motorcycles made.

Underneath the black paint and bright polish of the engine’s outer surfaces, most of what is there remains as before. Since a few problems were reported, having to do with transmission oil seeping through a keyway on the primary gear and then continuing into the right cylinder, an O-ring is now installed on the crank near the gear to curtail the seepage. That is the whole and part of mechanical changes made to the 1975 RD350 Yamaha.

Several of our “Feedback” column letters have made mention of plug fouling problems with the RD350s; i^iy wrote in with their own solutions. Plug fouling has been non-existent with our test model and with several other Yamaha two-stroke Twins we’ve had the opportunity to spend considerable time on. We think in most cases it’s simply a matter of the rider idling the machine around continually without ever opening up the throttle to clean out the cylinders a bit. At times the wrong fuel is used in our readers’ bikes, other times the wrong plugs. Our test machine was not specially tuned or prepared; it was quite typical of one that you would find on a dealer’s floor. And in all types of riding, around town, freeway, heavy traffic, drag strip and long distance, it showed no signs of plug fouling or misfiring. But there’s a way to ride the RD properly, precisely why a superb six-speed gearbox is standard equipment.

YAMAHA RD350B

$1071

Climbing on the machine you’ll again notice its relatively small size and light weight. Both the center and side stands are easy to use and are convenient (the sidestand features a tab extension to allow the rider to reach the stand from a sitting position on the motorcycle), as are the remainder of the important controls. The ignition key operates the lock on the seat latch (which can be left unlocked if the rider wishes), and the fuel tank cap. The tank holds 3.2 gallons of fuel, which is good for more than 100 miles of riding before reserve is necessary. The cap deserves mention. It’s of the spring-lüÄjpd flip-up variety, but it flips up away from the rider. Its hii^ is located forward, so when the cap is up it becomes a fairly solid obstacle. Not only that, in the interest of styling, the cap is shaped attractively, unless its in the “up” position, in which case the protruding edges present knife-like jagged edges to whatever happens to contact it. In case of an accident, there remains the unlikely possibility that the cap could pop open, exposing its immobile self to an object traveling forward at great speed (i.e., the rider’s body, a very vulnerable part of it). There is simply no excuse for such an oversight.

Instruments are the usual tach and speedo;a resettable trip odometer is included as well. The two dials are contained in a single housing that also positions the ignition switch directly in the center of the panel, nestled between a group of warning lights. The top two glow orange with the operation of the turn indicators, the bottom left acts as a taillight monitor and shines red whenever you touch the brakes (as long as the taillight is working). The remaining one stays red when the high beam is used. Both are far too bright; the monitor is a wasteful distraction of a gimmick, the high beam warning^ko bright that the rider would almost prefer to use low beain to eliminate the red glow from his eyes. A nice soft blue (ala BMW) would be ample for the beam warning. The other warning we can do without completely. Another minus: the Hat angle of the instrument faces reflects sunlight directly into the rider’s eyes.

One almost expects an electric starter on the 350, yet there is none and one is not needed. If the engine is cold the choke lever should be depressed; once the ignition and fuel are on, all that should be needed is a few light kicks of the starter lever. The choke is required for maybe 30-45 seconds in 50-degree weather; the engine is ready to go after that.

There might be a burble or two before the engine is warmed and running crisply, but it lasts for only a minute. The six-speed transmission is the perfect mate for this humming little Twin. Pick any speed, you’ve got the perfect ratio for it. At 60 mph, for example, you could run in 6th at an easy pace as long as the road was level and the wind wasn’t blowing strongly straight at you. Hit an incline and snick into 5th: lust enough gear to keep the engine smiling. And when that sj^^on the 750 comes blowing past you and you feel up to playing, drop to 4th and go get him.

Braking on our test bike got better as the miles piled on. Initially there was some sponginess with the operation of the front disc, but it disappeared later in the test. This one feature gives the 350 a great advantage over the smaller RD250. The disc is large (10.5 in.) the caliper is fixed in place, and the two live pucks are each 1.75 in. in diameter, the same size as those on Yamaha’s larger machines. High lever pressure is nonexistent due to the use of two slave cylinders in conjunction with the master cylinder. Pressure exerted on the disc by the pucks is tremendous, without muscling effort required at the lever. Braking on the Yamaha, with a conventional but operationally good drum rear brake, is excellent.

The Yamaha should be reasonably economical to operate, needs little in the way of special tools or knowledge to maintain and provides excitement and fun on a level that few street motorcycles can match. Check the next article about our RD350 cafe racer project. It’ll show you just how fa^ou can go with the RD350. But as it stands in standard^Pm, surprises are in store. Underneath that business suit is a set of full racing leathers. Go ahead...the wife won’t ever catch on!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMotorcycles, Rehabilitation And A Funky Jamboree

November 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

November 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

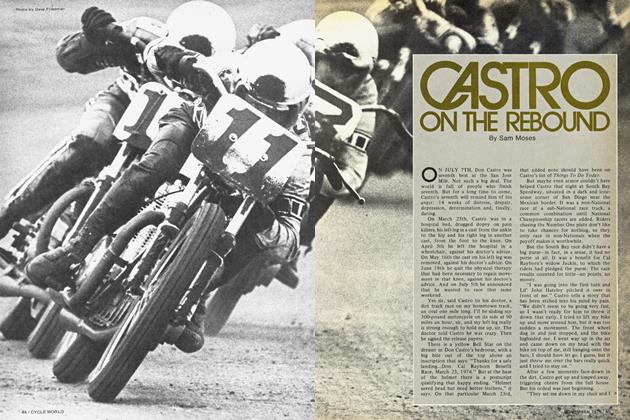

FeaturesCastro On the Rebound

November 1974 By Sam Moses -

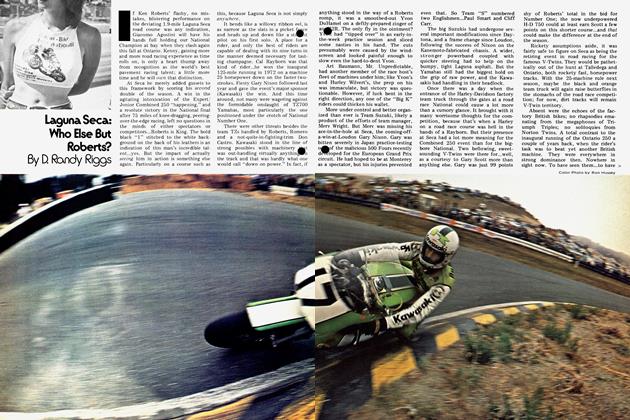

Competition

CompetitionLaguna Seca: Who Else But Roberts?

November 1974 By D. Randy Riggs