UP FRONT

THE BASIC ROAD RIDER OR "A CLOSED MOUTH CATCHES NO FLIES"—Cervantes

CYCLE WORLD is and always has been a general interest bike magazine. This means that we try to include something that will interest every biker in each and every issue. We try, but we do not always succeed, because our readers have varied preferences to an extreme.

When I first considered this dilemma, I thought minority groups would suffer most. But this isn't the case, because the novel approach minorities often have attracts the press, us included. The ones who really suffer are those who tour and ride the street daily!

To help alleviate this imbalance in our coverage, a new column is being added entitled “The Basic Road Rider." It's written by Dan Hunt, CW's former Senior Editor, and present Publisher of our sister publication, Pickup, Van & 4WD. Dan will cover virtually everything from basics to advanced techniques. Here's the first installment.—Bob Atkinson

So you have yourself a crotch-rocket? It goes like the wind and you’re happy.

I’m glad if you’re glad.

And the main point I want to make before getting down to business is that this column will not be the typical shuck for safety. Anyone who has been on the wrong end of a car-bike encounter doesn’t need the traditional slow-down talk about safety.

Mainly I’m concerned with extreme competence. We’ve got all the slack-jawed two-wheeled safety robots we need. The ultimate safety is in competence, and complete control of your machine. This column won’t make you a racer. But it will help you understand the principles of racing as they are applied to street riding. It will help you understand why a machine behaves the way it does; and how to feel the city street/country road environment in which you’ll be riding.

Motorcycle road riding is sport. It always will be, in spite of the people who are trying to dull it into being mere transportation. If you treat it like mere transportation, you’ll come out the loser. Bikes don’t offer the well-padded metal insulation that straight-arrow transportation does. The moment that riding becomes less than a challenge to you, less than an opportunity to improve, less than the sheer excitement of being on the way for no other reason than the feeling of freedom and novel movement, you’re setting yourself up for the Big One.

Motorcycle riding should boost the adrenalin. It should be part paranoia—watching for the heat, casting careful glances at the dinosaur people, who, in spite of their own wishes to the contrary, are out to get you. Motorcycling, even with its most up-to-date techno-mechanical trappings, is an expression of the raw man, the real man, the man who desires to relate in a realistic, physical manner to his environment.

You’re out there, exposed to all error, dealing with only the laws of physics, the laws of chance, the laws of people, and oftentimes with Nature itself.

It’s you and your reflexes, your body, your bike and your brain. And, hopefully, when the action is getting a bit heavy, you’ll have the self-honesty to know when enough is enough.

EVERY MAN'S MOTORCYCLE

The motorcycle rides on two wheels, one in front of the other, and if left to its own devices will fall down, collide with something or otherwise attempt to destroy itself.

Accompanied by a reasonably willing human being, the motorcycle becomes a semi-stable device. It continues in a straight line until the rider, from sheer boredom with straightness bids it to turn.

Its comportment over the ground is intriguing to the senses. It banks like an airplane. Magically almost, it needs no external outriggers or other support to keep it erect and rolling effortlessly through the countryside, hissing over the pavement until the reluctantly given moment when it slows to a stop and gently yields to the pressure of hands on the controls and deftly alighting feet during the last millisecond of forward motion.

In these motions, the rider senses a certain rightness. An economy of being, taking no more room than is necessary. It’s a motion that is closely allied to the body. Changes in attitude and direction seemingly execute themselves with only the slightest wish from the brain.

With the motorcycle’s economy and simplicity Come certain compromises and contingencies of which you should be aware.

The mysterious force that keeps the motorcycle erect when it is rolling is not mysterious at all. That force is actually several things operating at once. In fact, the so-called straight path of a motorcycle is really the sum of thousands of minor corrections each minute.

Some of these corrections are rider-induced. (And so are some of the errors!). The bike starts falling to the right, and the rider turns to the right. The front wheel and then the rear moves to the right faster than the rest of the machine; pretty soon the center of gravity of the bike is balanced directly over the place where the wheels touch and form a line with the ground, and the falling stops. Or if the correction was made too greatly, the wheel line moves to the right of the c.g. and the bike begins falling to the left.

The rider may also balance the machine by shifting his own weight, relative to the center of gravity, which, of course, will change the center of gravity. As his moving action has an equal and opposite reaction, however^some other correction must be executed jointly with his ^pt in weight to arrive at the desired balance.

Yet another form of correction is induced by the motorcycle’s own natural tendency to turn in on itself. This tendency is created by two things. As the motorcycle falls to the side in one direction, the front wheel geometry is such that the leaning of the motorcycle will cause the wheel to turn in the same direction. This results in the wheels tending to center themselves under the center of gravity, much as if the rider had turned the bars himself. The feature of geometry that is in play here is called “trail.” The more trail a bike has designed into it, the more it wants to go straight.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 4

Working with trail has the effect of changing the spot on which the tire contacts the ground. Engineers call this spot a “contact patch.” When the bike is straight up, the contact patch centers on the center line of the wheel. When the bike leans to the right, the contact patch moves over to the right side of the tire. And when it does move, it also tends, because of rolling friction against the ground, to turn the wheel to the right. The effect is slight, but it does aid the self-centering.

Also, let’s not forget the effect of centrifugal force, which trys to right the bike and lessen the rate of turn, and in so doing becomes progressively less forceful. Finally it reaches zero force, when the rate of turn is zero.

And what about the gyroscopic force of the wheels turning? It is not very significant, except perhaps at very high speeds. Its basic use to the motorcyclist comes from its retarding effect. It smooths the forces that tend to change the bike’s attitude and helps in banking the machine steadily into a turn. Gyroscopic precession actually aids the leftward banking tendency of a motorcycle on which the front wheel is being turned right momentarily. Crank the wheel left, and there will be a slight rolling force to the right.

Like the Family Stone says, “You can feel it if you try.” But I wouldn’t preoccupy myself with gyroscopic force. It’s just one factor in the interplay of several things that bring balance to you and your machine.

It is this continually modified state of balance—or sum of dynamic imbalances—that make the motorcycle a unique form of transportation. Balance, and the need to bank when making a turn are the joy of motorcycling and they are also what you have to live with.

These conditions will affect your braking ability. Straight up, on a dry, clean surface, the motorcycle can be one of the most effectively stopping instruments in existence. Its low weight and relatively massive braking capacity combine to produce stopping ability far beyond that of most production cars.

When the bike isn’t straight up, or when the condition of the road surface is less than perfect, that massive stopping power can work against the rider.

The reasons are clear. Straight up, the weight is made to transfer to the front wheel. The harder the braking, the more weight transferred to the front wheel and the more tire-to-road adhesion produced—up to the absolute limit of the tire compound’s traction. If the bike is banked for a turn, that weight transfer is not pushed straight down into the pavement, but is vectored to the outside of the turn. Exceed the traction capability of the tire, and the front wheel washes out. If you were driving an automobile, the washout would have little consequence—other than pronounced understeer. On a motorcycle, you don’t have a four-wheel platform to hold you up. Crash!

Acceleration works much the same way. Up to a point, the weight transfer of bike and body pushing rearward and downward on the rear tire increases traction. But should the bike be banked, the sum of the weight transfer pushes not down, which would help increase traction, but out, which helps to defeat traction. Hence, the seemingly carefree way in which one can powerslide an automobile does not belong to the average motorcyclist who rides the highway. Sliding with power on the dirt works fine for a biker, because the transition between full traction and no traction is broad and gentle. On the pavement, the transition is so rapid that a tail slide and subsequent recovery will throw your neck out of joint.

Pavement bikes may be drifted to a certain extent, however. With most production bikes, and standard tire compounds, a two-wheel drift can be produced when cornering at expressway speeds, this assuming that bad spring and shock absorber combinations don’t wobble you off the road first, or that your centerstand or tailpipes don’t wedge you off. The drift cannot be so pronounced it is on an automotive motoring platform, and it results partly from the distortion of the tires themselves in creating a “slip-angle.” Slip-angle is the difference between where the front tire is pointed and where it is actually going. It is, in effect, your leeway between ecstasy and disaster.

Because of the effect of drift and that of weight transfer either forward or rearward, you will discover that a motorcycle corners most stably when the throttle is on—not a hell of a lot—but on. Probably you’ve had the experience of entering a turn too hot already. “Zowee, I’m h-h-h-h-h-hot,” you mutter in fright, and roll the damn thing off. Of course, your fear has made you do the wrong thing, just like quivering student pilots who raw-reflex their planes into the most compromising of bounces.

Shutting off a rapidly cornering motorcycle produces forward weight transfer. Not only does it cause added front tire distortion, which tends to make more slip angle necessary to produce the same rate of turn, but it also lessens rear tire distortion and the back tire drift that was aiding your turn in a minute way. And finally, the apparent weight of the machine is now moved forward. The bike^^ now loaded like a playing dart. And, as everybody kno\^JP anything like that is going to fly itself straight off the turn.

Now you’re beginning to understand why I’ve called this chapter “Every Man’s Motorcycle.” That, in effect, is what I’m describing. There are no exceptions. He’s got a Twin, you’ve got a Four. Both are stuck with the same immutable laws.

To summarize, here's what you have going for you and working against you on a motorcycle:

WORKING FOR YOU

1. Economy of materials, fuel and motion.

2. Excellent forward visibility.

3. Excellent power-to-weight ratio.

4. Rapid response and maneuverability.

5. Ability to heighten rider’s attention.

6. Great braking ability and fade resistance—straight up.

WORKING AGAINST YOU

1. No insulation or protection.

2. Distraction from noise and wind.

3. Need to partially isolate banking from either rapid acceleration or braking.

4. Poor rearward visibility.

5. Inadvertent changes of balance and direction from minor body or head movements.

6. Detriment of design or component defects.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

October 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

October 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Competition

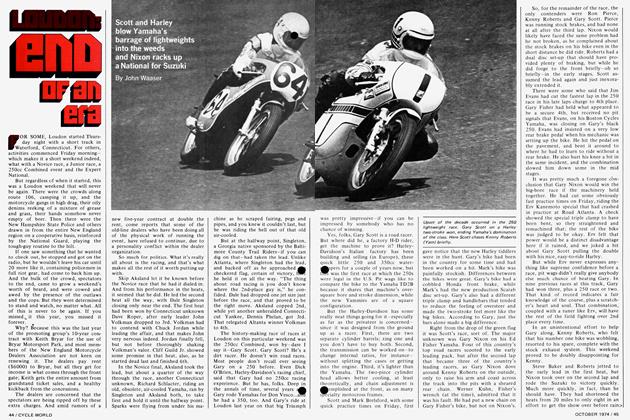

CompetitionLoudon: End of An Era

October 1974 By John Waaser -

Competition

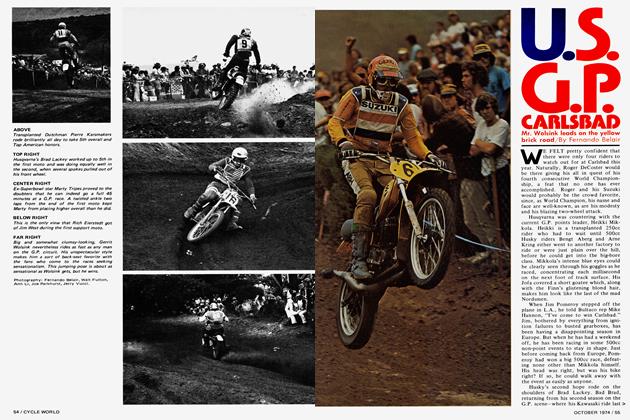

CompetitionU.S. G.P. Carlsbad

October 1974 By Fernando Belair -

Features

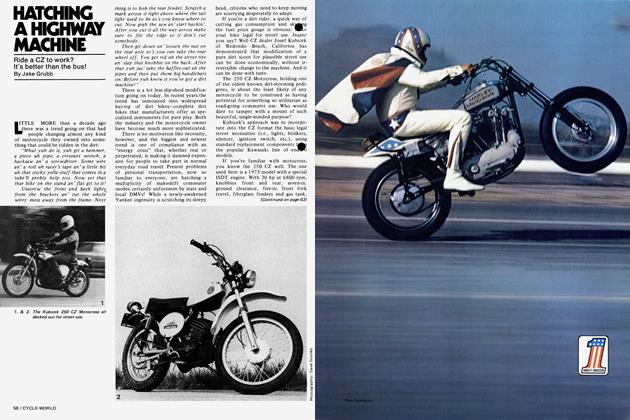

FeaturesHatching A Highway Machine

October 1974 By Jake Grubb