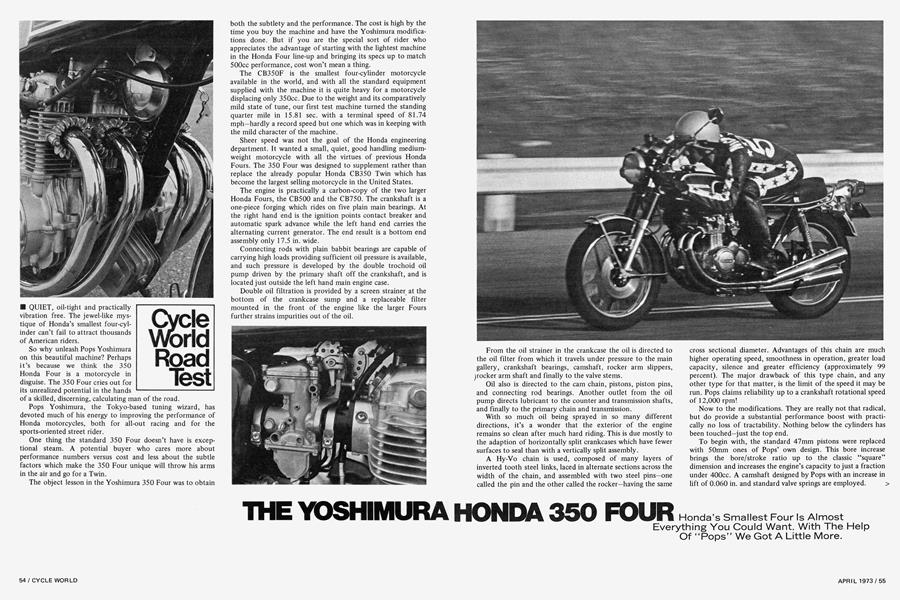

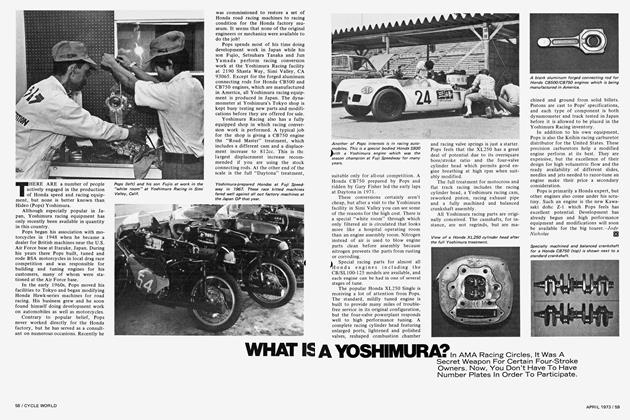

THE YOSHIMURA HONDA 350 FOUR

Cycle World Road Test

QUIET, oil-tight and practically vibration free. The jewel-like mystique of Honda’s smallest four-cylinder can’t fail to attract thousands of American riders.

So why unleash Pops Yoshimura on this beautiful machine? Perhaps it’s because we think the 350 Honda Four is a motorcycle in disguise. The 350 Four cries out for its unrealized potential in the hands of a skilled, discerning, calculating man of the road.

Pops Yoshimura, the Tokyo-based tuning wizard, has devoted much of his energy to improving the performance of Honda motorcycles, both for all-out racing and for the sports-oriented street rider.

One thing the standard 350 Four doesn’t have is exceptional steam. A potential buyer who cares more about performance numbers versus cost and less about the subtle factors which make the 350 Four unique will throw his arms in the air and go for a Twin.

The object lesson in the Yoshimura 350 Four was to obtain both the subtlety and the performance. The cost is high by the time you buy the machine and have the Yoshimura modifications done. But if you are the special sort of rider who appreciates the advantage of starting with the lightest machine in the Honda Four line-up and bringing its specs up to match 500cc performance, cost won’t mean a thing.

The CB350F is the smallest four-cylinder motorcycle available in the world, and with all the standard equipment supplied with the machine it is quite heavy for a motorcycle displacing only 350cc. Due to the weight and its comparatively mild state of tune, our first test machine turned the standing quarter mile in 15.81 sec. with a terminal speed of 81.74 mph—hardly a record speed but one which was in keeping with the mild character of the machine.

Sheer speed was not the goal of the Honda engineering department. It wanted a small, quiet, good handling mediumweight motorcycle with all the virtues of previous Honda Fours. The 350 Four was designed to supplement rather than replace the already popular Honda CB350 Twin which has become the largest selling motorcycle in the United States.

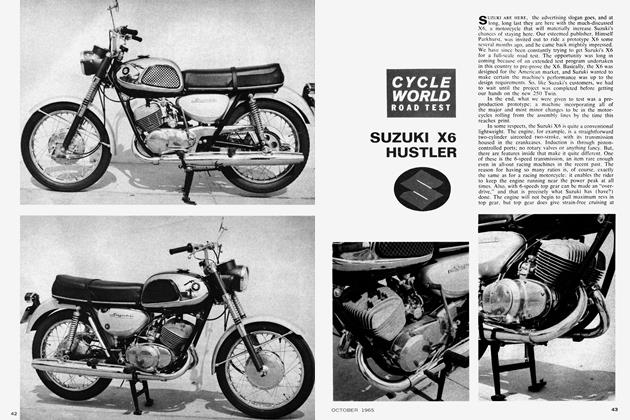

The engine is practically a carbon-copy of the two larger Honda Fours, the CB500 and the CB750. The crankshaft is a one-piece forging which rides on five plain main bearings. At the right hand end is the ignition points contact breaker and automatic spark advance while the left hand end carries the alternating current generator. The end result is a bottom end assembly only 17.5 in. wide.

Connecting rods with plain babbit bearings are capable of carrying high loads providing sufficient oil pressure is available, and such pressure is developed by the double trochoid oil pump driven by the primary shaft off the crankshaft, and is located just outside the left hand main engine case.

Double oil filtration is provided by a screen strainer at the bottom of the crankcase sump and a replaceable filter mounted in. the front of the engine like the larger Fours further strains impurities out of the oil.

Honda’s Smallest Four Is Almost Everything You Could Want. With The Help Of “Pops” We Got A Little More.

From the oil strainer in the crankcase the oil is directed to the oil filter from which it travels under pressure to the main gallery, crankshaft bearings, camshaft, rocker arm slippers, jrocker arm shaft and finally to the valve stems.

Oil also is directed to the cam chain, pistons, piston pins, and connecting rod bearings. Another outlet from the oil pump directs lubricant to the counter and transmission shafts, and finally to the primary chain and transmission.

With so much oil being sprayed in so many different directions, it’s a wonder that the exterior of the engine remains so clean after much hard riding. This is due mostly to the adaption of horizontally split crankcases which have fewer surfaces to seal than with a vertically split assembly.

A Hy-Vo chain is used, composed of many layers of inverted tooth steel links, laced in alternate sections across the width of the chain, and assembled with two steel pins—one called the pin and the other called the rocker—having the same

cross sectional diameter. Advantages of this chain are much higher operating speed, smoothness in operation, greater load capacity, silence and greater efficiency (approximately 99 percent). The major drawback of this type chain, and any other type for that matter, is the limit of the speed it may be run. Pops claims reliability up to a crankshaft rotational speed of 12,000 rpm!

Now to the modifications. They are really not that radical, but do provide a substantial performance boost with practically no loss of tractability. Nothing below the cylinders has been touched—just the top end.

To begin with, the standard 47mm pistons were replaced with 50mm ones of Pops’ own design. This bore increase brings the bore/stroke ratio up to the classic “square” dimension and increases the engine’s capacity to just a fraction under 400cc. A camshaft designed by Pops with an increase in lift of 0.060 in. and standard valve springs are employed. >

The cylinder head has received the most attention with recontoured inlet ports and extensive reshaping of the combustion chambers. None of the modifications have altered the excellent low-speed pulling power of the engine, and it is possible to accelerate smoothly up the speed range from 1000 rpm in top gear without any lurching or bucking.

The proof of the pudding is in the performance, however, and during that phase of testing we got a mouthful. With over a dozen standing start quarter mile runs our elapsed times never varied more than 0.2 sec. and the terminal speed was always in the 90 mph bracket, quite a substantial increase over the completely standard CB350F we tested last year. The only unpleasantness noticed was a very slight tendency for the machine to hesitate from idle speed to 1 /8th throttle, probably caused by improper adjustment of carburetor slow speed jets.

It should be mentioned that the standard 20mm Keihin carburetors and unmodified exhaust pipes were used during the tests. Even the air cleaner, which causes a slight drop in performance, was left as fitted by the factory.

Outwardly, the CB350F was left untouched from its Japanese configuration. All instruction plaques were in Japanese, the speedometer was calibrated in kilometers per hour, and there was a red light on the top of the fork stem which illuminated whenever 80kph (approximately 50 mph) was exceeded. Otherwise the machine was in standard USA configuration except for the engine.

Any time a radical change is made within an engine the balance factor often changes significantly, creating periods of unwanted and often severe vibration. Such is not the case with the Yoshimura Honda CB350F. The vibration point at 6000 rpm is still there to an extent, and as the revs and power loadings increase, so does the severity of the vibration. But at no time even up to an indicated tachometer reading of 11,000 rpm did the vibration’s severity become intolerable.

Although the Yoshimura engine begins pulling strongly at 6000 rpm, there is plenty of smooth power below that figure with no cam effect evident. The engine idles smoothly at 1200 rpm.

Another feature of the CB350F we especially liked was the brakes, both front and rear. The front disc pulled the 396-lb. machine down from high speed with unfailing reliability in a straight line time after time, and practically no fade was experienced from the rear brake.

In most instances high braking performance is just as important as high speed performance. Although we didn’t run our first CB350F through our timing clocks for a top speed reading, the Yoshimura Honda CB350F clocked an amazing 105 mph, which we consider to be a very good speed) considering the standard gearing, air cleaners and mufflers. Truly a wolf in sheep’s clothing!

Handling has never been a big point with Honda four-cylinder models, due in part to their sheer weight and bulk and to their marginal rear suspension units. Side and center stands have also hindered cornering power to the left, but these items have been left out to the side to facilitate their location and operation by the rider. The side stand is particularly easy to actuate because it has a steel ring welded to its end which is easy for the rider’s foot to find.

Ground clearance is also very good. The four gracefully upswept mufflers provide more than adequate ground clearance and add a rakish air to the rear end of the machine. These mufflers and the cleverly designed air intake system keep the motorcycle’s noise very low, and there is a practically no mechanical noise from the finely designed and constructed engine.

Flicking the Honda from side to side through our favorite canyon road, we found excellent tracking on smooth surfaces.) But the rear shock absorbers showed their weakness when traversing bumpy roads. During the morning when the ambient air temperature was cool they behaved quite nicely, but in the afternoon when the temperatures rose the dreaded “pogo” effect began to show itself.

Although the Honda is a small, short coupled machine, riding two up was not uncomfortable for short distances unless one of the riders was a large person. Whereas the larger CB750 Four can be compared to a Cadillac, the CB350F shows itself as a Vega in terms of passenger comfort.

The relationship between the seat, footpegs and handlebars is definitely better suited to a rider of smallish stature, but its low center of gravity and good steering geometry make steering at low speeds practically effortless. The CB350F is definitely an around town machine, one which is more suited to pleasure trips through the neighborhood than cross-country jaunts.

If owning a maneuverable, docile motorcycle appeals to you, take a good look at the CB350F. If you want the same motorcycle With more performance, consider the Yoshimura conversion.

YOSHIMURA HONDA

350 FOUR