THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

THE OVERWHELMING success story of Soichiro Honda has been told many times. It would be redundant to go into much depth about the brilliant engineering genius of the man who reconditioned some old surplus generators in the early 1950s and went on to create a mind-boggling motorcycle manufacturing giant so well-known that throughout the free world the word Honda means two-wheelers.

I deliberately used the term “word” Honda, because you would be hard put in this country of 200 million people to find many who do not know that a Honda is a motorcycle. On the other hand you could, I think, find that many people do not know that the word Honda is the name of a man.

Along with building a motorcycle company to manufacture about 3,000,000 motorcycles each year, Mr. Honda also created Honda R&D (research and development). Located outside of Tokyo, Honda R&D now employs about 1000 technicians and engineers. It has jokingly been called Mr. Honda’s play shop because that is where the “old man” spends most of his time and effort. Probably because he is somewhat bored with the rather mundane aspects of producing so many motorcycles, Mr. Honda prefers the engineering freedom of R&D. But the R&D facility is much more than a play shop. Far from the constraints of realizing production targets, R&D is free to build exotic grand prix racers and develop new metals, tooling and manufacturing techniques that would seriously slow down a production plant.

So now we have a basic idea of the man and Honda R&D. And most of us know that Honda also produces cars. Compared to motorcycles, Honda’s car efforts have not been earthshattering as far as Americans are concerned. The N600 is being sold in this country and although it is just about bulletproof, it is noisy and somewhat strained to keep up with expressway traffic. On the other hand the domestic N360 (360cc) cars and trucks have just about dominated Japanese sales since their introduction several years ago.

While still a strong motorcycle enthusiast at heart, Mr. Honda is very committed to becoming a leading auto manufacturer. As in the case of motorcycle riders who later take up car racing (Joe Leonard, Joe Weatherly, John Surtees, Mike Hailwood, etc.), the auto world kind of pooh-poohed any threat from Honda. But they didn’t reckon with the genius, dedication and drive of Soichiro Honda.

On learning of forthcoming U.S. Federal emission standards, and the threat of strong Japanese regulations against autos in that smog-ridden country, Mr. Honda called together about 70 percent of the R&D work force to develop a clean engine. That was almost two years ago and since we are talking about 700 engineers and technicians a total of about 1400 man-years went into coming up with a solution to the problem.

Even to meet current 1973 emission standards for California, most auto manufacturers have had to tack on a bunch of unreliable and expensive inductionrelated control equipment. In order to reduce pollutants per mile, especially NOx, compression ratios have gone down. To compensate for power loss, engines are getting bigger, and the actual fuel consumption greater.

In his original dictate to R&D, Mr. Honda, a true environmentalist, demanded a small, clean engine—an engine that would be in line with current technology (reciprocating), but one that would not deplete resources any more than absolutely necessary.

Anyone watching Honda stock on the market these days will realize that something happened at Honda. Like John Surtees going on to become world champion, or Joe Leonard bagging the USAC crown, Honda, barely in the first dozen auto manufacturers in the world, did it. The handwriting was on the wall last year when a dozen of the world’s auto giants went to court against our Federal government, stating that it was impossible to meet the forthcoming 1975 emissions standards, but Honda did not join in the court action. Rather, and with no fuss, Honda submitted a car to the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) for the required 50,000-mile clean air reliability test. The car did not feature an afterburner or a problem-ridden catalytic muffler system. The engine was, in fact, a fairly normal piston-engined device with a slightly different cylinder head, and it received a clean bill of health (so to speak) from EPA.

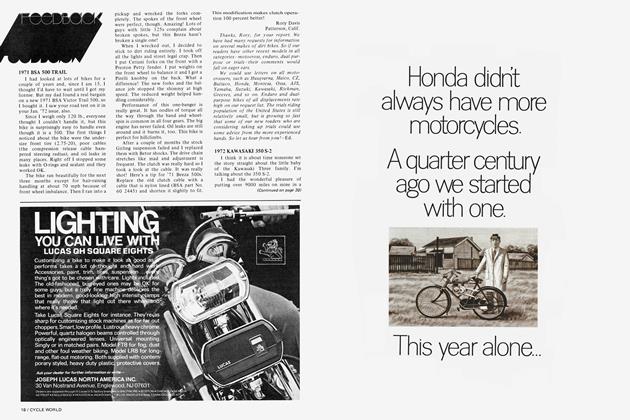

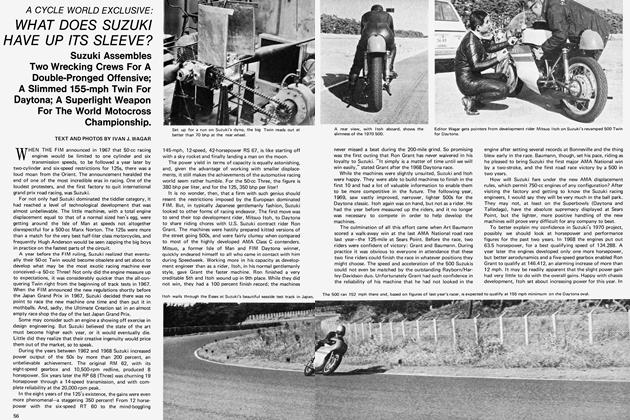

Termed CVCC (Compound Vortex Controlled Combustion), Honda’s new engine works on the stratified-charge principal. Separated from the main combustion chamber by a small passage, a pre-combustion chamber accommodates an over-rich fuel charge. On the power stroke, after ignition in the tiny prechamber, the expanding over-rich charge enters the main chamber which has been supplied with a very lean fuel-to-air mixture. The final result is that total ignition and gas expansion occurs over a fairly long period of time, and comparatively complete intake gas burning takes place within the working cylinder. Thus Honda has been able to operate at a fairly high (possibly 9:1) compression ratio, and maintain good power output from a small engine.

When he introduced the new Honda car (called the Civic) and CVCC, Mr. Honda noted that several auto giants throughout the world were interested in the design. It’s no wonder. The CVCC requires only a carburetor and cylinder head change to existing piston-type engines. Honda has more than 100 patents on an updated old idea. Pre-combustion chambers have been around for a long time in diesel engines. Even the great Harry Ricardo applied the pre-combustion principle to tank engines in 1917, during WWI. But Honda’s play shop—the expression of a demanding genius—has brought the concept forward for our benefit.