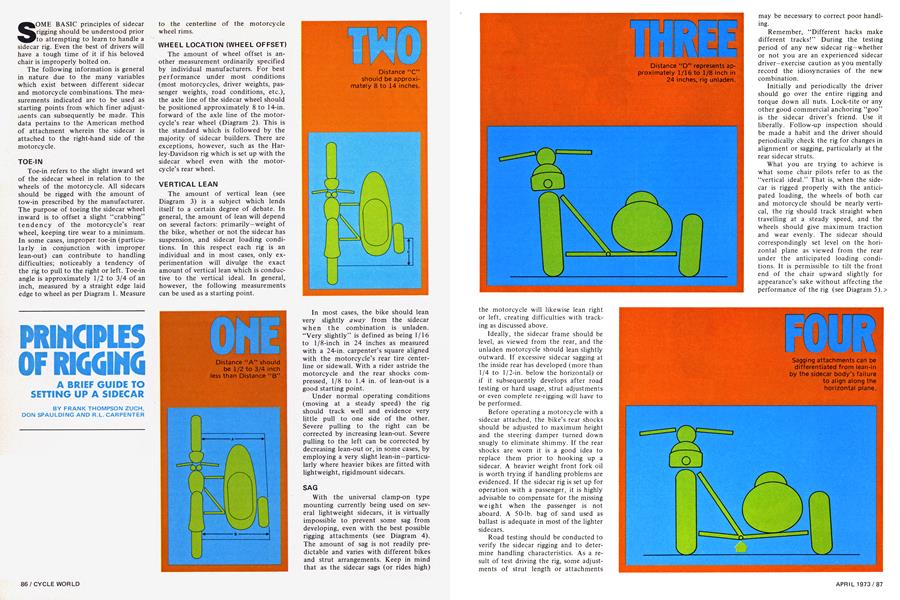

Principles of Rigging

April 1 1973 Don Spaulding, Frank Thompson Zuch, R.L. CarpenterPRINCIPLES OF RIGGING

A BRIEF GUIDE TO SETTING UP A SIDECAR

FRANK THOMPSON ZUCH

DON SPAULDING

R.L. CARPENTER

SOME BASIC principles of sidecar rigging should be understood prior to attempting to learn to handle a sidecar rig. Even the best of drivers will have a tough time of it if his beloved chair is improperly bolted on.

The following information is general in nature due to the many variables which exist between different sidecar and motorcycle combinations. The measurements indicated are to be used as starting points from which finer adjustments can subsequently be made. This data pertains to the American method of attachment wherein the sidecar is attached to the right-hand side of the motorcycle.

TOE-IN

Toe-in refers to the slight inward set of the sidecar wheel in relation to the wheels of the motorcycle. All sidecars should be rigged with the amount of tow-in prescribed by the manufacturer. The purpose of toeing the sidecar wheel inward is to offset a slight “crabbing” tendency of the motorcycle’s rear wheel, keeping tire wear to a minimum. In some cases, improper toe-in (particularly in conjunction with improper lean-out) can contribute to handling difficulties; noticeably a tendency of the rig to pull to the right or left. Toe-in angle is approximately 1/2 to 3/4 of an inch, measured by a straight edge laid edge to wheel as per Diagram 1. Measure to the centerline of the motorcycle wheel rims.

WHEEL LOCATION (WHEEL OFFSET)

The amount of wheel offset is another measurement ordinarily specified by individual manufacturers. For best performance under most conditions (most motorcycles, driver weights, passenger weights, road conditions, etc.), the axle line of the sidecar wheel should be positioned approximately 8 to 14-in. forward of the axle line of the motorcycle’s rear wheel (Diagram 2). This is the standard which is followed by the majority of sidecar builders. There are exceptions, however, such as the Harley-Davidson rig which is set up with the sidecar wheel even with the motorcycle’s rear wheel.

VERTICAL LEAN

The amount of vertical lean (see Diagram 3) is a subject which lends itself to a certain degree of debate. In general, the amount of lean will depend on several factors: primarily—weight of the bike, whether or not the sidecar has suspension, and sidecar loading conditions. In this respect each rig is an individual and in most cases, only experimentation will divulge the exact amount of vertical lean which is conductive to the vertical ideal. In general, however, the following measurements can be used as a starting point.

In most cases, the bike should lean very slightly away from the sidecar when the combination is unladen. “Very slightly” is defined as being 1/16 to 1/8-inch in 24 inches as measured with a 24-in. carpenter’s square aligned with the motorcycle’s rear tire centerline or sidewall. With a rider astride the motorcycle and the rear shocks compressed, 1/8 to 1.4 in. of lean-out is a good starting point.

Under normal operating conditions (moving at a steady speed) the rig should track well and evidence very little pull to one side of the other. Severe pulling to the right can be corrected by increasing lean-out. Severe pulling to the left can be corrected by decreasing lean-out or, in some cases, by employing a very slight lean-in—particularly where heavier bikes are fitted with lightweight, rigidmount sidecars.

SAG

With the universal clamp-on type mounting currently being used on several lightweight sidecars, it is virtually impossible to prevent some sag from developing, even with the best possible rigging attachments (see Diagram 4). The amount of sag is not readily predictable and varies with different bikes and strut arrangements. Keep in mind that as the sidecar sags (or rides high) the motorcycle will likewise lean right or left, creating difficulties with tracking as discussed above.

Ideally, the sidecar frame should be level, as viewed from the rear, and the unladen motorcycle should lean slightly outward. If excessive sidecar sagging at the inside rear has developed (more than 1/4 to 1 /2-in. below the horizontal) or if it subsequently develops after road testing or hard usage, strut adjustments or even complete re-rigging will have to be performed.

Before operating a motorcycle with a sidecar attached, the bike’s rear shocks should be adjusted to maximum height and the steering damper turned down snugly to eliminate shimmy. If the rear shocks are worn it is a good idea to replace them prior to hooking up a sidecar. A heavier weight front fork oil is worth trying if handling problems are evidenced. If the sidecar rig is set up for operation with a passenger, it is highly advisable to compensate for the missing weight when the passenger is not aboard. A 50-lb. bag of sand used as ballast is adequate in most of the lighter sidecars.

Road testing should be conducted to verify the sidecar rigging and to determine handling characteristics. As a result of test driving the rig, some adjustments of strut length or attachments may be necessary to correct poor handling.

Remember, “Different hacks make different tracks!” During the testing period of any new sidecar rig—whether or not you are an experienced sidecar driver—exercise caution as you mentally record the idiosyncrasies of the new combination.

Initially and periodically the driver should go over the entire rigging and torque down all nuts. Lock-tite or any other good commercial anchoring “goo” is the sidecar driver’s friend. Use it liberally. Follow-up inspection should be made a habit and the driver should periodically check the rig for changes in alignment or sagging, particularly at the rear sidecar struts.

What you are trying to achieve is what some chair pilots refer to as the “vertical ideal.” That is, when the sidecar is rigged properly with the anticipated loading, the wheels of both car and motorcycle should be nearly vertical, the rig should track straight when travelling at a steady speed, and the wheels should give maximum traction and wear evenly. The sidecar should correspondingly set level on the horizontal plane as viewed from the rear under the anticipated loading conditions. It is permissible to tilt the front end of the chair upward slightly for appearance’s sake without affecting the performance of the rig (see Diagram 5).>

PACKING

When it comes time to pack the new sidecar for a trip, there are a few rather obvious techniques involved to achieve the best performance. The first thing to remember is to lighten the left side of your combo and add weight to the right. Clothing, empty Oly cans, nerf balls and such will go into your left saddlebag and scoot boot. Tent stakes, full six packs, and assorted Stilson wrenches go into the right bag or into the sidecar.

If no passenger is along for the journey, play it safe-put everything in the car. Make certain that gear packed in the car is securely lashed down. Sidecars have a lamentable habit of bouncing sundry items out onto the freeway at inopportune moments.

TROUBLE-SHOOTING

Achieving the vertical ideal with a new set-up is usually a trial and error process of adjusting the relationship of sidecar to motorcycle until the combination performs correctly. Since the odds are strong against this happening the first time around, here is a review of a few things to look for when specific problems are encountered.

SHIMMY AND TIRE WEAR

There are three separate types of front end oscillation. The first and least serious wobble is referred to as “headshaking.” This phenomenon is present in the majority of sidecar rigs and usually appears when decelerating at lower speeds—for example, when slowing for a traffic light. It is virtually a universal characteristic and should be scarcely noticeable if the driver keeps both hands on the handlebars where they should be. For a shimmy which develops when a bump or chuck hole is hit, tighten the steering damper. If the shimmy is more severe, producing a pronounced front end wobble, and does not disappear with acceleration, worn out rear shock absorbers on the motorcycle are suspect and might require replacement.

Excessive or pattern wear results from insufficient toe-in of sidecar wheel. The solution is to increase toein.

SPECIFIC RIG CHARACTERISTICS

Lightweight to mediumweight sidecars tend to appear somewhat eccentric during the driver’s learning process because they accentuate the centrifugal effects, particularly when turning to the right. With practice and experience, however, they can be surprisingly agile. Beginners are advised to stay within their own personal limits at all times.

With experience, utilizing more advanced techniques (using front brake in righthanders, breaking the rig loose on lefthand turns, riding with the sidecar wheel off the ground, broadside panic stops, bootleg turns) the lightweight hack becomes amazingly versatile. Even empty chair right-handers can be accomplished with alacrity. But these are offered as later possibilities...they are not recommended for the beginner.

Rigid frame sidecars are more prevalent among the lighter sport rigs, and they are characterized by an increased tendency to lift when turning to the right. They are great for the short haul, but become somewhat bouncy as the trek lengthens. These rigid, no-suspension rigs are quite similar to racing outfits and consequently can be drifted to the left very easily. It is advisible to be aware of the weight relationship of the motorcycle to the sidecar when setting up the lightweight models.

A heavier motorcycle will place considerable stress on the struts and attachments in a left-hand turn. A slight lean-in may be called for in the rigging because when the rider mounts the bike, the compression of the rear shocks will bring the outfit to the proper vertical alignment.

SUSPENSION

When the chair features suspension (either at the wheel or beneath the rig proper), the distinguishing factor is a reduced facility for drifting into the corners. This is because sidecars tend to give against stress, thereby maintaining friction between tire and road. As a consequence, the fully suspended sidecar is less amenable to rough cornering, particularly to the left. Comfort is much improved. Suspended rigs are usually set up near vertical (unladen) because motorcycle rear shocks and chair suspension compress approximately the same when rider and passenger are aboard.

Heavyweight sidecars are not as versatile or agile as their lighter brethren, but are infinitely more comfortable. This comfort factor approaches true luxury in some of the enclosed English models which feature cut-glass vases and plush upholstery. Options are often available which offer complete rain protection. Most offer brakes on the sidecar wheel. You pay for this weighty luxury by trimming speed, particularly in the corners. The large, heavyweight sidecars ordinarily require definite lean-out and more toe-in in order to reduce steering fatigue.