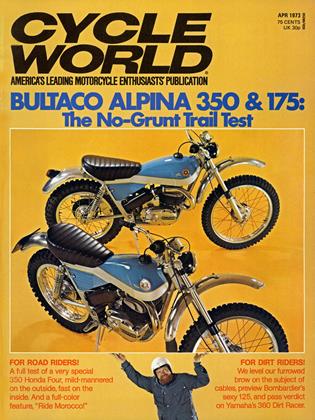

MOROCCO

Take Your Bike To Contrast-Country, Where European Culture Co-Exists With Bedlam. Haggle With An Arab, Sidle Up To A Snake Charmer, Or Isolate Yourself From The Whole Scene And Ride Off Into The Desert.

Edwin Thorne Jr.

MOROCCO IS an ideal country to travel by motorcycle. For most of the year the weather is clear, roads are generally in good condition and, because Morocco is a small country, the distances between points of interest are not prohibitive for motorcycle travel.

During our second day in Morocco the motorcycle’s ability to attract a crowd resulted in an interesting side trip that my wife, Missie, and I hadn’t counted on. The Rif Mountains have for centuries served as an invincible fortress along Morocco’s northern border. Until recently, the road through the Rif was virtually impassable. The beautiful beaches along the Mediterranean at the foot of these mountains are still undeveloped, but the road has been improved and offers the visitor some truly spectacular scenery—tall pine trees, sharp corners and patchwork patterns of tiny farms in the valleys.

KIEF AND HASHISH

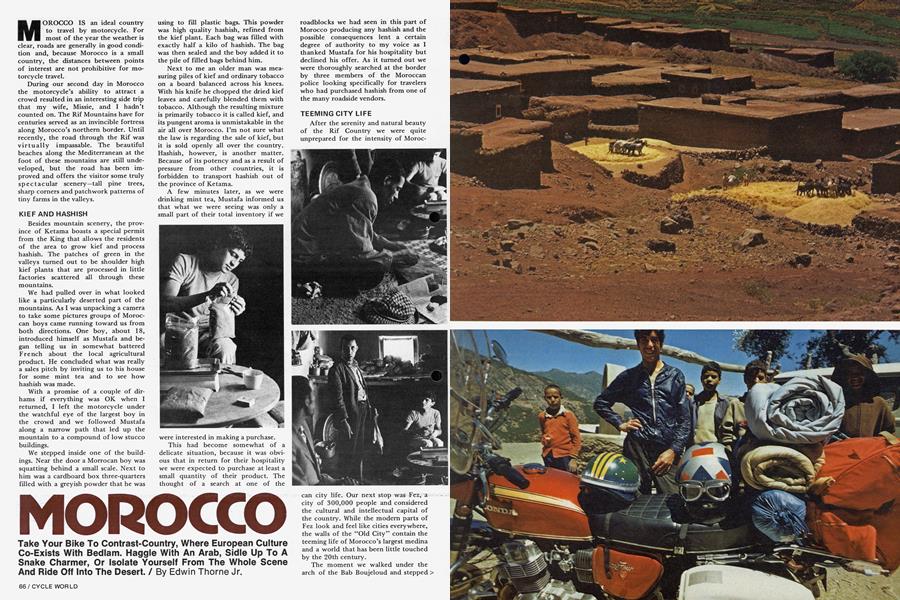

Besides mountain scenery, the province of Ketama boasts a special permit from the King that allows the residents of the area to grow kief and process hashish. The patches of green in the valleys turned out to be shoulder high kief plants that are processed in little factories scattered all through these mountains.

We had pulled over in what looked like a particularly deserted part of the mountains. As I was unpacking a camera to take some pictures groups of Moroccan boys came running toward us from both directions. One boy, about 18, introduced himself as Mustafa and began telling us in somewhat battered French about the local agricultural product. He concluded what was really a sales pitch by inviting us to his house for some mint tea and to see how hashish was made.

With a promise of a couple of dirhams if everything was OK when I returned, I left the motorcycle under the watchful eye of the largest boy in the crowd and we followed Mustafa along a narrow path that led up the mountain to a compound of low stucco buildings.

We stepped inside one of the buildings. Near the door a Morrocan boy was squatting behind a small scale. Next to him was a cardboard box three-quarters filled with a greyish powder that he was using to fill plastic bags. This powder was high quality hashish, refined from the kief plant. Each bag was filled with exactly half a kilo of hashish. The bag was then sealed and the boy added it to the pile of filled bags behind him.

Next to me an older man was measuring piles of kief and ordinary tobacco on a board balanced across his knees. With his knife he chopped the dried kief leaves and carefully blended them with tobacco. Although the resulting mixture is primarily tobacco it is called kief, and its pungent aroma is unmistakable in the air all over Morocco. I’m not sure what the law is regarding the sale of kief, but it is sold openly all over the country. Hashish, however, is another matter. Because of its potency and as a result of pressure from other countries, it is forbidden to transport hashish out of the province of Ketama.

A few minutes later, as we were drinking mint tea, Mustafa informed us that what we were seeing was only a small part of their total inventory if we were interested in making a purchase.

This had become somewhat of a delicate situation, because it was obvious that in return for their hospitality we were expected to purchase at least a small quantity of their product. The thought of a search at one of the roadblocks we had seen in this part of Morocco producing any hashish and the possible consequences lent a certain degree of authority to my voice as I thanked Mustafa for his hospitality but declined his offer. As it turned out we were thoroughly searched at the border by three members of the Moroccan police looking specifically for travelers who had purchased hashish from one of the many roadside vendors.

TEEMING CITY LIFE

After the serenity and natural beauty of the Rif Country we were quite unprepared for the intensity of Moroccan city life. Our next stop was Fez, a city of 300,000 people and considered the cultural and intellectual capital of the country. While the modern parts of Fez look and feel like cities everywhere, the walls of the “Old City” contain the teeming life of Morocco’s largest medina and a world that has been little touched by the 20th century.

The moment we walked under the arch of the Bab Boujeloud and stepped > into Fez’s medina our senses were bombarded by a heady mixture of sights, sounds and smells. Crowds of people and animals swirled through the narrow streets—there were herds of goats, donkeys carrying such things as refrigerators on their backs, and groups of running children. Being jostled is all part of the game and we soon learned to let ourselves move freely with the crowd. It is nearly impossible to remain stationary in the middle of this turmoil for more than a few seconds at a time.

The Arab’s bargaining skill and the possibility of a language difficulty shouldn’t deter anyone from jumping in with both feet and trying to beat a shopkeeper at his own game. The first thing to remember is that the original quoted price will have nothing to do with the true value of the item. This is particularly true in the sections of the medina that are heavily traveled by tourists. In one of these areas I managed, after a theatrical bargaining session, to buy a leather bag for $7 that had originally been priced at $55.

After a reasonable period of haggling if you still haven’t settled on a price, your best tactic is probably to walk out of the store, mumbling something about how you know that you can buy the same thing for less somewhere else. Chances are that in a few minutes the salesman will run down the street after you, saying he has had time to reconsider your offer and would like to reopen the bargaining.

MOROCCAN RESTAURANTS

Lunch in a spectacular Moroccan restaurant provided a striking contrast to the activity of our first morning in Fez. The noise and turmoil of the streets were left behind when we entered the Dar Saada and found ourselves in a world of cool, tiled serenity. Instead of chairs there were large cushions on the floor which invited a moment of horizontal relaxation and the opportunity to study the incredibly beautiful combination of colors, textures and patterns that covered the ceiling and walls.

In a moment an Arab, looking cool and comfortable in his long white robe, appeared at our table with a brass pitcher and bowl. The pitcher was full of water that we used for washing our hands. This ritual was particularly important because in a Moroccan restaurant most of the food is taken by hand from a communal plate.

Some mint tea followed by a short nap on the cushions completed our midday meal and prepared us for a return to the medina. Lunch had taken nearly four hours, which is about normal in Morocco. During the early afternoon the inhabitants of the medina escape from the intense heat and the streets are deserted. Around 4:00 the wooden doors are thrown back and the shops come to life again. The streets begin to get crowded and the noise level builds as though someone was turning up a giant volume control. It doesn’t take long for the medina to return to the intensity of the morning.

As we strolled through the narrow streets we realized that we had become somewhat numbed to the frantic pace around us for, out of what at first had seemed like complete chaos, we began to focus on some of the details. The aroma of bread being baked, the groups of boys braiding brightly colored threads with one end tied to a nail in the side of a building and the other more than 100 feet away, and the metallic ring of cold chisels banging out decorative patterns in brass plates—these were things that our senses had passed over during our earlier confusion. We found ourselves stopping to look in the window of a shop that sold nothing but gold teeth or staring, fascinated, at the rhythmical motion of needles in the hands of men doing embroidery.

In our preoccupation with this frantic world around us we failed to notice how far we had proceeded into the labyrinth of the medina. Suddenly every street looked the same and we realized that we were hopelessly lost. After we passed the same shop for the third time when I thought that we had been traveling in a straight line, I knew that we needed help. As though he had been reading my mind, a young Moroccan boy approached us and offered his services as a guide. He knew that we needed him more than he needed us so the bargaining session was rather onesided, but we managed to arrive at a reasonable price for his help and were on our way.

Guides in Morocco, no matter what age, get a kickback of 25 percent on anything that you spend in a store that they take you into. We also learned that “no” or “I’m not interested” means absolutely nothing to a Moroccan the first 10 times that he hears it. Both these bits of information came into play as we tried to keep our guide out of an endless number of shops. Our persistence in avoiding the stores and insisting on a direct route earned us the nickname of “American Express” from our guide, who finally did manage to get us back to familiar territory.

A CHANGE OF PACE

After three days in the highly charged atmosphere of Fez we were ready for a change of pace and decided to head south to the village of Azrou. Azrou is located in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains, and besides being a main crossroad for the area it is the location of a weekly souk, or market, that is the principal source of livestock for the entire region.

We timed our arrival for the afternoon before the weekly souk. Already the town was filled with farmers and sheepherders from the surrounding countryside, anxious for the chance to swap stories and gossip before the activities of the following day. Several storytellers had attracted a large crowd in a field at one end of town. Each storyteller was surrounded by Arabs who were watching every gesture and facial expression as if hypnotized. The fantasy of the legends that were being told in that field and in hundreds of fields like it across the country is a basic form of entertainment in Morocco that hasn’t changed for centuries.

People began to drift away from the crowd as evening approached to take up positions in the surrounding countryside to watch the sun go down. Every evening the hills around Fez had also been filled with Arabs squatting on the ground, while the sun settled over their city. This hour of the day is an important time in this Moslem religion for prayer and meditation. A solitary Arab squatting motionlessly on the side of a hill facing the sun as it expands almost to the point of bursting before sliding silently behind the smokey silhouette of the Atlas Mountains is a truly magnificent sight.

The next morning the crowds congregated in another large field to buy and sell livestock. As the sky lightened, the silence of early morning was replaced with the sounds of business—Arabs wandering among the herds of sheep, goats, donkeys and cattle; teeth being examined, eyes checked, ribs poked and animals lifted to estimate their weight. All this activity was conducted in a noisy atmosphere of good-natured back-slapping, laughter and pushing and shoving. Every few minutes an animal would break away from its herd and chaos would result as his owner chased him through the crowd, inevitably setting loose several other animals. Despite an attempt to identify them by spraying them with patches of colored dye, getting the animals back into the hands of their owners produced a good deal of confusion.

By 9:00 the sun had warmed the crisp mountain air and the livestock trading had been completed. Somehow, who owned what was sorted out and the herds of animals were led out of the field to the hills around the town. At this point attention shifted to the market that had been set up under and around a group of tents at one end of the field.

COMMUNITY MARKETS

In every town of any size in Morocco there are souks like the one in Azrou. > They provide an opportunity for the people from the surrounding countryside to come together not only to sell their goods but also to exchange local gossip and buy the necessities of life. Like all markets in Morocco this one had every conceivable item for sale. One table was piled high with dried lizards, stuffed wolf heads and other objects used in the practice of witchcraft, which was very popular in this part of the country. Another table contained an incredible display of screws, bolts, bathroom fixtures, bicycle parts and an assortment of all kinds of junk. The poverty in the country plus the Moroccan’s ability to sell, swap or find a use for almost anything, no matter how broken down, results in an efficient recycling process where hardly anything is thrown away.

There are many prolific weavers in the Berber tribes around Azrou and this souk is also known for having an assortment of high quality rugs. In one section of the souk these rugs stand in rows, folded in such a way that they resemble Arabs in their colorful djellabas squatting on the ground. One of these examples of Berber craftsmanship caught my wife’s eye and, despite my plea that we didn’t have room for a rug on the already fully loaded motorcycle, she made a beeline for the picturesque old Arab presiding over this section of the market.

Missie started to talk to him in French and, although he responded by making a series of strange marks in the dirt, it was obvious that she wasn’t having very much luck getting the bargaining process started because the old man couldn’t understand anything but Arabic. Another man came over to act as a translator but at this point nothing seemed to help. The minute that the old Arab realized that he was not going to be able to bargain with us directly he lost all interest in the sale and just sat stonelike, looking out over his rugs. Here was a perfect example of the importance that an Arab places on being able to haggle over the price of anything that he is buying or. selling. If this is denied him, the transaction will often lose all meaning.

THE SAHARA DESERT

Later that morning we left the commotion of the Azrou’s souk and started a journey over the northern end of the Atlas Mountains and out into the Sahara. Our destination was the tiny oasis of Rissani, which, although only 160 miles from Azrou, is in a different world—a world where the harshness and power of the land becomes the dominant factor in man’s ability to survive.

Our route for this part of the trip was truly a motorcyclist’s dream. A good road surface and long, sweeping turns carried us over the Camel Pass, down through the Gorges du Ziz and into Ksar el Souk, the administrative and commercial center for the Tafilalet region and the last large town before the desert takes over the landscape.

From Ksar el Souk the road went straight out into the desert, across a plateau that became more barren as the miles sped by. At the bottom of a trench-like valley that runs nearly parallel to this road was the river Ziz. We weren’t aware of the river being close by until we rounded one of the only curves on the road and without warning found ourselves at the edge of the plateau, looking down hundreds of feet into a long valley. Tall date plums are clustered along both sides of the river and every inch of level ground has been cultivated to form a patchwork pattern in shades of green. The road descended one wall of the valley and followed the river for a few miles before it left the vegetation behind and returned to the level of the desert.

As the miles went by the temperature continued to climb and the landscape began to take on that endless quality of a true desert. The road continued across the sand to Erfoud and on to the oasis of Rissani, with its giant palm grove sitting on the edge of the Sahara like a monument to the last vestige of living things in the ground. This was the end of the highway and the beginning of hundreds of miles of nothing but sand. Nearby were the ruins of Sijilmassa, once the Roman outpost that controlled many of the desert trade routes during the Middle Ages and, at that time, one of the most powerful and important cities in the country. Today, the crumbling walls that remain make a strong statement about the changes that modern transportation technology has caused in the desert.

Despite recent efforts by the government to inject some life into the economy of the desert we couldn’t help but notice the poverty throughout this area, as its inhabitants worked to maintain some sort of an existence from the cruel and unproductive landscape. With the end of the trade routes across the sand the desert lost its principal reason for supporting life. There are still a few bands of nomads roaming across this ocean of sand but it is a dying breed of men.

DETAILS & DETAILS: THE KIND THAT MAKE A BETTER TRIP

Our trip to Morocco was made during the first two weeks in August. Transportation was a 1971 Honda 750 which was purchased in New York and, after breaking it in, was then shipped by air to Madrid, Spain. The bike was sent via TWA because it was the only airline that would ship it uncrated.

I carried the following spare parts and tools on the trip: A front and a rear inner tube plus two cans of compressed air to inflate the tires, extra points and condenser, four extra spark plugs, a second clutch cable, the factory tool kit with the addition of an extra set of wrenches, an adjustable wrench, and a large screwdriver (the screwdriver set in the tool kit doesn’t have the strength to remove any of the major screws on the bike), a bag of assorted nuts and bolts, a supply of wire and some strong tape for emergency repairs.

Before the bike was shipped to Spain I outfitted it with the following accessories:

Windshield— Th is is a valuable addition for any long trip on a motorcycle, not only as protection against things thrown up from the road, but also to reduce the fatigue from long hours of driving into the wind.

Air Horns— This is one accessory that I can’t recommend highly enough. Although they are expensive, they make a great deal of noise, which is an effective method of keeping cars and trucks from cutting you off. The horns also were a useful warning device while driving on the narrow roads and around the blind corners in the mountains.

Saddlebags— The ones I used were fiberglass, made especially for the Honda 750. These bags look small but we found after a bit of experimentation that we were able to squeeze quite a bit into them. Not only did the bags allow some of our luggage to be carried low to reduce the center of gravity, but they also provided us with a lockable storage place. This was particularly valuable to me because of my camera equipment. 1 also found that the fiberglass was a good insulator and therefore helped to keep my film cool during the times when the temperature climbed to over 110 degrees.

Crash Bars—/ installed these on the bike primarily for protection while it was being shipped. In addition to offering protection the bars prevented the bike from falling all the way over on its side in case of a spill. This made it possible to lift the bike back to the vertical position without having to lighten it by taking off most of the luggage.

Luggage Rack— This was the only thing that caused us any real trouble during the trip. The rack I installed was the type that fastens to the frame and is supposed to keep any weight off the rear fender. In theory the design is fine, but it didn’t work because of faulty materials. Within a few hundred miles the brackets attaching the rack to the bike had bent so that the rack was resting on the rear light bracket. By the end of the trip the rear fender had been bent and the bolts that held the rack and the shock absorbers to the frame were badly stripped.

I had underestimated the amount of stress that is put on a luggage rack during a long trip. What looks like a good arrangement for carrying all your gear while the bike is standing still will more than likely have to be modified when the wind and the effects of rough roads have had a chance to do their thing. My advice would be to get a good set of saddlebags and a strong “sissy bar”for lashing down the bulky stuff. Forget the luggage rack because ultimately it will put too much strain on the rear fender.

Aside from several stops to repair the luggage rack the only problem that we faced during the trip was a flat tire caused by my accidentally running over a set of spikes that the police used at one of the road blocks we had to deal with. Luckily the flat occurred near a gas station that was equipped with tire irons, for without the irons I would have had a difficult time changing the tire.

The bike ran perfectly on the gas in both Spain and Morocco. The only maintenance I performed was an oil and oil filter change. I turned off the automatic chain oiler in favor of applications of Chain Life at every gas stop. This kept the chain in good condition even after hours of continuous high speed driving. Honda seems to have solved the problem of the chain stretching on the 750 because after the first 500 miles the chain on my bike never had to be adjusted.

At the end of the trip the plugs looked almost new and the engine was running smoothly at all speeds although it had lost some of that little “edge” that a well-tuned 750 has when you really crank open the throttle.

Basically I have only good things to say about the Honda 750 as a touring bike. Besides being able to carry huge amounts of luggage its smooth and effortless power makes it an easy machine to ride for hours at a time. I’ll have to admit that a fully loaded 750 is a real handful to maneuver through city traffic, particularly at the end of a long day of driving; but this is really a small price to pay for a motorcycle that, for us, was a perfect vehicle for a long trip through a strange country.

We drove through the cooling air back to Erfoud, where we planned to stay in the Hotel du Sud. This hotel is one of a chain of large, modern hotels that the government’s tourist office has constructed along the northern edge of the Sahara in an attempt to stimulate tourist traffic to this remote part of Morocco. Although the hotels are somewhat institutional, such comforts as a swimming pool and air conditioning were welcome luxuries after a long and hot day on a motorcycle.

When we checked into the hotel we found out that the air conditioning had broken down. By the time we had finished dinner the air had cooled enough to be comfortable but when we returned to our room we discovered that the pillows and mattress were still hot to the touch from the heat they had absorbed during the day.

All the windows were opened wide to catch every breath of air moving across the still desert as we lay on the hot mattress listening to the sounds of the night.

At one point during the night a strong wind blew across the desert, slamming windows and churning up high quantities of sand. The wind ended as abruptly as it had begun and the desert returned to an uneasy stillness. Although short-lived, this wind had a strength behind it that made us thankful to be inside the thick walls of the hotel.

The wind, noise and heat had their effect during the night and we awoke the next morning rather bleary-eyed from a lack of sleep. Several cups of Moroccan coffee managed to jolt our senses back to life and we proceeded to load the bike for the day’s drive. This operation always produced a crowd of spectators who stood by silently, amazed at the amount of luggage we were able to pile on the back of the motorcycle. Packing had become an art because of the stuff we had purchased along the way for which we had to find room.

When we reached the outskirts of Erfoud we saw the results of the night’s wind. Loose sand up to 6-in. deep covered sections of the road and made keeping the heavily loaded bike upright a tricky proposition. After one minor fall, which luckily resulted only in damage to my ego, we arrived back in Ksar el Souk.

BARREN LANDSCAPES

From Ksar el Souk we followed the Kasbah Road west, along the northern edge of the Sahara. There are few signs of life in this part of the country where even the buildings of dried earth blend into the horizon. The green of a distant oasis or the bright colors worn by many of the local women provided an occasional contrast to the endless panorama of muted reds, browns, and soft yellows. There is a timeless quality about this land where life in the Ksours has remained at its most basic and the 20th century seems far far away.

(Continued on page 130)

Continued from page 72

Brief stops for something cool to drink were our only respite from the monotony of driving for hours in a perfectly straight line with little to look at except the sand. Clouds overhead saved us from the effects of the desert sun but, nevertheless, it was a long, hot and exhausting day of seemingly endless driving at 70 or 80 miles per hour. By mid afternoon we reached the village of Quarzazate where the local Hotel du Sud’s swimming pool and comfortable beds managed to eliminate most of the effects of a long day’s driving in the desert.

MOUNTAIN PANORAMAS

The next morning we got an early start on the final leg of our journey to Marrakesh. A few miles outside of town Quarzazate the “Kasbah Road” leaves the desert and begins a climb towards the Tizi N’ Tichka pass which, at over 7500 feet, is the highest in the Atlas Range. The road to the summit provided some truly spectacular mountain panoramas as we negotiated a seemingly endless series of switchbacks. This was a pleasant change from the previous day, for not only was the temperature cool and comfortable, but also the road through the mountains was made for a motorcycle and was fun to drive.

After the summit, we began the tortuous descent to the Marrakesh Plain, where the temperature often soars past 110 degrees. The trip from Quarzazate had taken longer than planned, so by the time we started across the plain it was the hottest part of the day. The last few miles into Marrakesh turned out to be the most uncomfortable part of our trip. A brutal sun overhead and a hot wind in our faces rapidly drained our strength and forced us to rest every few minutes.

PICTURESQUE MARRAKESH

After an hour or so of this madness we reached Marrakesh and the relief of a cold drink at a sidewalk cafe. With its wide boulevards, dusty pink buildings and magnificent gardens, Marrakesh is certainly one of Morocco’s most picturesque cities. Its location had made this city an important meeting place for nomads from the Sahara, Berber craftsmen from the mountains and the farmers from the surrounding plains. The combination of cultures, skills and interests that these diverse groups bring with them has given Marrakesh a unique ambiance and feeling of friendliness that is highly contagious.

(Continued on page 132)

Continued from page 130

There was a 12-year-old Moroccan running his father’s shoe store while his father was on a buying trip in the desert, who was a little dynamo of enthusiasm, anxious not only to make a sale but to make two friends while doing it. He plied us with endless glasses of Coke and told us about the difference in quality between various types of Moroccan slippers.

We bought some babouches for our two boys and he presented us with a minature pair to give to them as a souvenir. As we were leaving he told us that he regretted not being able to have us to his home because his father was away. This offer was not unusual, for although they will gladly relieve you of every dirham in your pocket, should an Arab befriend you, you will find yourself the recipient of boundless hospitality and generosity.

Perhaps the most famous meeting place in the country is Marrakesh’s Djemaa-el-Fna. This sprawling square just inside the walls of the old city becomes a veritable 10-ring circus every afternoon as acrobats, snake charmers, storytellers, musicians, dancers and merchants of all kinds compete for the visitor’s eye. Although there are many foreign tourists in the square, the majority of people enjoying the various forms of entertainment are Arabs from the surrounding countryside for whom a visit to Marrakesh is their primary contact with the outside world.

The festive chaos that fills the Djemaa-el-Fna every afternoon is fueled by the pounding rhythm of the drums of the African dance troupe, the mournful cry of the snake charmer’s flute, the antics of the storytellers and the noise of hundreds of Arabs talking at each other. It is impossible to resist the energy generated by all this activity, which continues full blast until darkness falls on the medina. The openness and friendliness of this city made Marrakesh difficult to leave.

THE LAST LEG

Despite departing at an early hour, the plain that surrounds the city was already uncomfortably warm and the wind blew in our faces like the heat from an open oven door. For the next three hours the temperature continued to rise until we crested a small hill about five miles from the Atlantic Ocean and were greeted by a blast of almost cold air. The temperature dropped rapidly and in a few minutes we arrived in the little fishing village of Essaouira.

(Continued on page 139)

Continued from page 132

Portuguese sailors were the only ones able to maintain any kind of a foothold on this rugged section of the Atlantic coast and their influence is still evident in the white walls and blue shutters throughout this charming little village. The crowds of summer tourists who invade the beaches farther north haven’t yet discovered Essaouira’s sheltered bay, so there is still a peacefulness about the town. A quick tour led us to the dock where fishermen were bringing in their day’s catch and where, for a couple of dirhams, we experienced a true gastronomic treat—fresh sardines grilled over an open fire and topped with a little onion and lemon.

After our lunch on the dock we headed north along the windswept coast toward Casablanca. For an hour or so we looked down from the high cliffs to an extremely rocky and unfriendly beach before we came to a place where the ocean had broken through the rocks to form an inland bay and a beautiful, white sand beach. This was such a pleasant surprise that we decided to camp here for the night. As usual, the best location had been taken over by a private campground but for about 40 cents we were entitled to a piece of ground on which to set up our two-man Alpine tent.

The next morning, after somehow managing to get all our gear back on the motorcycle, we continued up the coast. As we neared Casablanca the road became more heavily traveled and we began to see colonies of summer cottages looking out over beautiful white beaches.

MODERN CASABLANCA

Casablanca itself, is a large, modern city that, except for the occasional appearance of a veiled woman on the streets, is very much like many other western cities. Tall buildings, streets clogged with automobile and bus traffic, plus the crowded sidewalks reflect the degree to which Casablanca is firmly entrenched in the 20th century. This area is the center of Morocco’s commercial and industrial activity.

After a night in Casablanca, which, for a city that Hollywood has glamorized as a capital of sin and smuggling, goes to bed very early, we began the last leg of our journey back to Tangier. Along the way we stopped in the capital city of Rabat for a look at the royal palace and the medina and Mellah, or Jewish quarter, both located high on the banks looking out over the river Bou Regreg.

(Continued on page 140)

Continued from page 139

From Rabat the road to Tangier crosses the Gharb Plain which contains some of the country’s richest farmland. Here tractors and trucks have replaced the donkeys and camels that we had seen throughout most of the rest of the country. Everything from wheat to tobacco and oranges to olives is grown on this exceptionally fertile land.

We crossed the river Mharhar and passed the remains of the custom house that used to mark the border before Tangier gave up its international status and returned to being a part of Morocco. In a few miles we arrived at on” starting point two weeks before—t city of Tangier.

A COUNTRY OF CONTRASTS

Sitting on the beach looking out over Tangier’s harbor, the whine of Arab music from hundreds of transistor radios provided a hypnotic background to the conversations in German, French, Spanish and English all around us. Bikinis abounded but there were also veiled women, covered from head to foot, sitting in the sand. This is truly a country of contrasts—the old and the new, the rich and the poor, the East and the West, even the jumble of designs and patterns on a palace gate that, in the hands of a Moroccan craftsman, somehow manages to create a feeling of unity out of what at first seemed like total chaos. (

The colors worn by the Berbc women, the aromas of the medina, the intricate beauty of the tile work and the maddening charm of a 12-year-old Arab boy were only a few of the ways that our senses had been bombarded from every side during our visit. There is an intensity about Morocco that demands a great deal from the visitor. One moment you find yourself loving the people for their warmth, enthusiasm and hospitality and the next moment, you’re ready to scream uncontrollably at their incessant pestering, hustling and harassment.

Although our trip had been short I couldn’t help but feel that the impressions made would be longlasting. The motorcycle had performed faultlessly and in many ways had made a positive contribution to the trip because of the people to which it had brought us contact. We boarded the boat to Ale ciras the next day with the hope that we would be able to return to Morocco in the not-too-distant future. |51