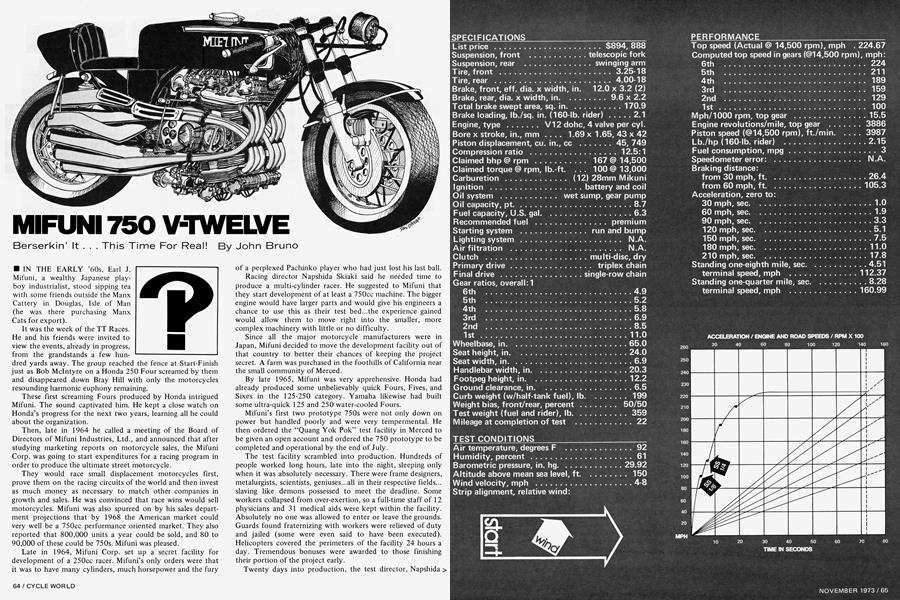

MIFUNI 750 V-TWELVE

Berserkin’ It . . . This Time For Real!

John Bruno

IN THE EARLY '60s, Earl J. Mifuni, a wealthy Japanese playboy industrialist, stood sipping tea with some friends outside the Manx Cattery in Douglas, Isle of Man (he was there purchasing Manx Cats for export).

It was the week of the TT Races. He and his friends were invited to view the events, already in progress, from the grandstands a few hundred yards away. The group reached the fence at Start-Finish just as Bob McIntyre on a Honda 250 Four screamed by them and disappeared down Bray Hill with only the motorcycles resounding harmonic euphony remaining.

These first screaming Fours produced by Honda intrigued Mifuni. The sound captivated him. He kept a close watch on Honda’s progress for the next two years, learning all he could about the organization.

Then, late in 1964 he called a meeting of the Board of Directors of Mifuni Industries, Ltd., and announced that after studying marketing reports on motorcycle sales, the Mifuni Corp. was going to start expenditures for a racing program in order to produce the ultimate street motorcycle.

They would race small displacement motorcycles first, prove them on the racing circuits of the world and then invest as much money as necessary to match other companies in growth and sales. He was convinced that race wins would sell motorcycles. Mifuni was also spurred on by his sales department projections that by 1968 the American market could very well be a 750cc performance oriented market. They also reported that 800,000 units a year could be sold, and 80 to 90,000 of these could be 750s. Mifuni was pleased.

Late in 1964, Mifuni Corp. set up a secret facility for development of a 250cc racer. Mifuni’s only orders were that it was to have many cylinders, much horsepower and the fury of a perplexed Pachinko player who had just lost his last ball.

Racing director Napshida Skiaki said he needed time to produce a multi-cylinder racer. He suggested to Mifuni that they start development of at least a 750cc machine. The bigger engine would have larger parts and would give his engineers a chance to use this as their test bed...the experience gained would allow them to move right into the smaller, more complex machinery with little or no difficulty.

Since all the major motorcycle manufacturers were in Japan, Mifuni decided to move the development facility out of that country to better their chances of keeping the project secret. A farm was purchased in the foothills of California near the small community of Merced.

By late 1965, Mifuni was very apprehensive. Honda had already produced some unbelievably quick Fours, Fives, and Sixes in the 125-250 category. Yamaha likewise had built some ultra-quick 125 and 250 water-cooled Fours.

Mifuni’s first two prototype 750s were not only down on power but handled poorly and were very tempermental. He then ordered the “Quang Yok Pok” test facility in Merced to be given an open account and ordered the 750 prototype to be completed and operational by the end of July.

The test facility scrambled into production. Hundreds of people worked long hours, late into the night, sleeping only when it was absolutely necessary. There were frame designers, metalurgists, scientists, geniuses...all in their respective fields... slaving like demons possessed to meet the deadline. Some workers collapsed from over-exertion, so a full-time staff of 12 physicians and 31 medical aids were kept within the facility. Absolutely no one was allowed to enter or leave the grounds. Guards found fraternizing with workers were relieved of duty and jailed (some were even said to have been executed). Helicopters covered the perimeters of the facility 24 hours a day. Tremendous bonuses were awarded to those finishing their portion of the project early.

Twenty days into production, the test director, Napshida Skiaki, suffered a breakdown caused, possibly, by the fact that he had not eaten or slept for 12Vi days.

$894, 888

The pace quickened. The rate of mental collapse among the cadre increased as the ever impending terminus drew nearer. Finally, on July 26th at 4 a.m., Pacific Daylight Time, the prototype (covered by a snug fitting tarpaulin) was rolled out of the Development Lab across the small parking lot separating the security complexes. Fifteen guards armed with M-16s equipped with infra-red scopes flanked the machine as it was being transported. A helicopter gun ship hovered menacingly above.

At 7 a.m. that morning, the mood changed. A 21-gun salute was given to those few who so gallantly gave of themselves for the common good of the company. A 2-min. silence was ordered while 14 hearses slowly moved by the 378 remaining workers. The silence was broken when all started singing the Mifuni company song, followed by another volley from the cannoneers. All of this, as the sun rose slowly in the East.

At 10 a.m., four factory riders arrived to be briefed on the machine. The tension broke as the machine was uncovered. It was painted fire engine red with yellow striping to highlight its sleek but bulky appearance.

“Gentlemen,” said the new acting test director, Odimake KushiKatsu, “the machine before you is a twelb syrinder, doubo ova head kamshaf, fo vawve per syrinder, sebin fifty motorcyco producing 167 blake hoss powah at 14,500 1pm.” But before he could go any farther, the four riders were grapling among themselves about which one of them wouldn’t have to ride it. All four resigned on the spot. Then, during the ensuing ruckus at the door, five security guards managed to convince reknowned test rider and good sport Furnley Yurd Mulhaine to stay (for a modest fee, of course). Bound, gagged and kicking, he was delivered to his quarters where he would remain under surveillance until the test the next morning at 9

a.m., sharp. The press was then notified.

Promptly at 9 a.m. the following morning, the bike was rolled onto the test track with Furnley strapped securely to it. (The press, represented by at least 50 publications, was told that the straps were for safety purposes only).

At 10:15 the engine was started and the radio transmitter on Furnley’s back was switched on. “The engine is responding very well,” reported Furnley. “It’s perking nicely at 12 to 14,500 rpm.... I am now releasing the cluuuu....” Furnley never finished.

Astonishing, was all that could be said (maybe, “Gosh”). The clocks shattered as Furnley smoked by the timing tower, recording a 0-100 time of 8.28 sec. The bike was said to have tripped the quarter-mile lights in third gear (Furnley only had time to shift twice), recording an unofficial 160.996 mph, but of course he went faster than that. (Eat humble pie, Harley-Davidson). Witnesses say Furnley kept the Twelve wide open all the way through sixth gear. The chase plane above reported sighting him just before he crashed into the base of a mountain nearly 20 miles away. Furnley apparently froze at the controls when the tachometer reached 14,500 in sixth (that translates out to roughly 220 mph).

Astounding as it may be, this all happened, so the two years of construction, completed at a cost of almost $895,000, was of little benefit.

In a press release the following day, president Earl J. Mifuni was quoted as saying, “If man was meant to accelerate, he would have been born with accelerator pumps. So, in view of the events which took place previously, and in honor of our fallen comrades, this company will now put its combined efforts toward completing construction of a not-so-menacing beast...the Mifuni 50cc “Five” and never again tread on such sacred grounds!”

But that’s another story.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

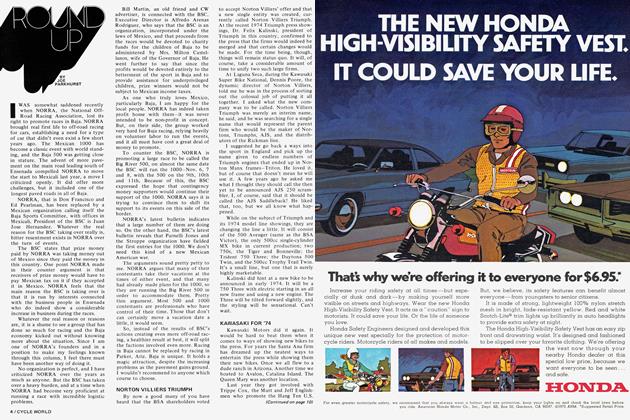

DepartmentsRound Up

November 1973 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1973 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

November 1973 -

The Scene

November 1973 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Competition

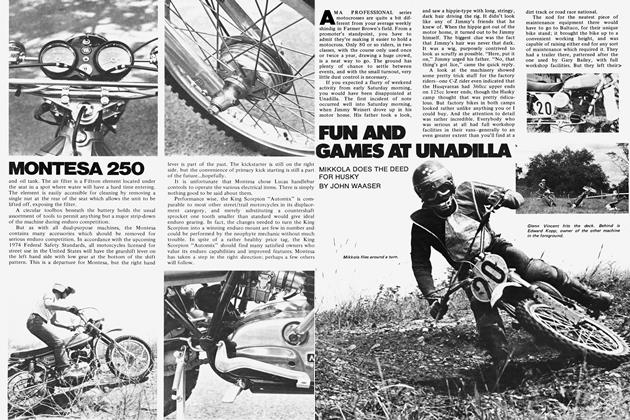

CompetitionFun And Games At Unadilla

November 1973 By John Waaser -

Competition

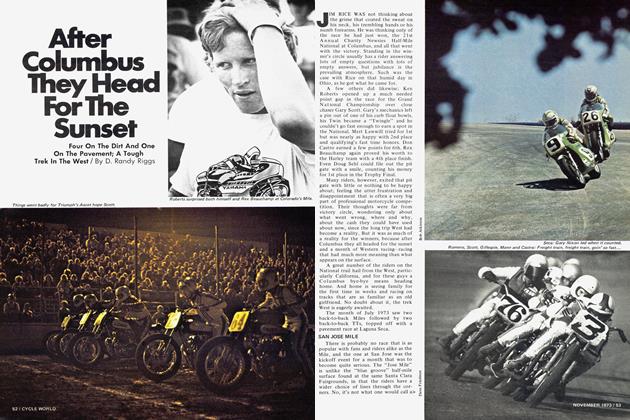

CompetitionAfter Columbus They Head For the Sunset

November 1973 By D. Randy Riggs