THE NOT SO EASY OUT

Thomas Lambrou

Break Off A Drill Or Bolt In An Expensive Part? If All Else Fails, Metal Disintegration And $5 Will Save You The Cost Of Replacement.

"I'M AFRAID there's not a thing we can do to help you." That's the response I received from a machine

shop when I asked for help in removing the screw extractor that broke while trying to remove the headbolt I'd twisted off.

I was torqueing down the headbolt nuts on my 305 Yamaha when the headbolt gave up (metal fatigue, I suppose) and my fingers, still clutching the torque wrench, polished a small area on the front forks. After recovering from the momentary hysteria of crushed knuckles, it seemed like a straightforward job of drilling the bolt, which had twisted off flush with the case, and backing it out with an E-Z out.

It was a strange feeling when the E-Z out broke. No smashed knuckles this time. I’d pulled the engine and had it safely secured on the workbench. With a crack that sounded like a hammer striking plate glass, the steel E-Z out shattered and only by sheer luck was I not hit by the shrapnel. My luck from there went straight downhill.

There was hardly anything left to get a hold on and the broken E-Z out was as firmly implanted in the bolt as the bolt was in the case. That’s when the machine shops started in with the disappointing news. After spending half the day driving and telephoning, one machinist suggested a metal disintegrating machine. At first I thought he was putting me on but he assured me such a device existed, but not in San Diego, Calif., that he knew of. He suggested a fellow whose company is appropriately named Jerry’s Drill and Tap Removal, 1018 E. Chestnut, Santa Ana, Calif.

I was apprehensive about how much this disintegration was going to cost. But replacing the case was not a financially enticing alternative, so I invested 55 cents in a telephone call to Jerry Grafton, head potentate and sole operator of Jerry’s. I described my problem and he said depending on how deep the bolt went it would cost up to $5 and he could do it while I waited.

I arrived at Jerry’s shop the following morning. I’d brought with me the engine and a lot of hope. In his shop were three Cammon C-86 metal disintegrating machines. Each one weighs 1800 lb. and can hold 40 gallons of oil soluble coolant. The working compound looks like a drill press, only larger, and will support four tons of work load.

There were several motorcycle engines and parts lying on the work table, some still waiting to be operated on. Yamaha International in Buena Park, Calif., sends over some of its “nearly no hope” problems.

When I came in Jerry was just finishing removing a broken drill from a valve which he explained came from an aeronautics firm. In the production of these valves, which are only the size of a salt shaker, they periodically break a drill bit while drilling a 1/16-in. hole. Since it usually breaks off deep, they have no way to get the broken bit out. The valves cost $200 each to manufacture. The company waits until they accumulate several, then sends them to Jerry. It’s always the same hole and he knocks them out one after the other and charges $1.80 each, thereby salvaging $198.20 for the company for each valve. Jerry’s prices are based on the time required and the amount of disintegration needed. He says that his machine doesn’t know whether it’s repairing a $ 10 part or a $ 1000 one.

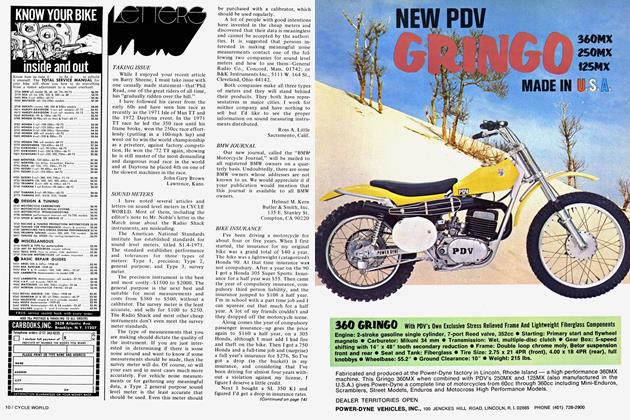

The process of disintegration is accomplished by creating a series of vibrating electrical arcs at the tip of a special electrode. At the same time coolant under pressure flows through the hollow center of the electrode and the rapid cooling of the metal creates a thermal shock that powderizes the metal, which is washed away by the coolant. Because the 5000-degree heat generated by the electrode is limited to that tiny portion of metal which is being disintegrated at the time, there is no annealing of the material around the hole so there’s no distortion or marring of the work piece.

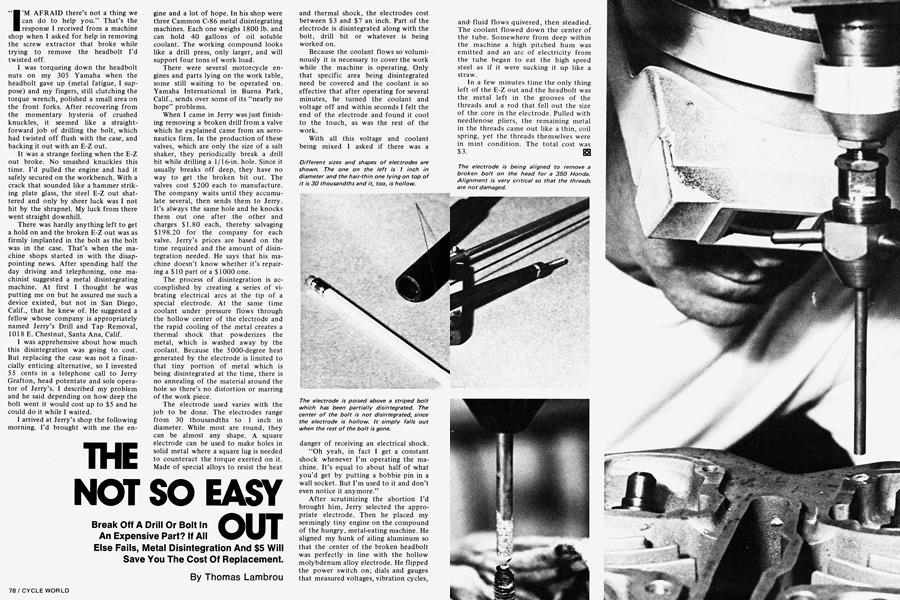

The electrode used varies with the job to be done. The electrodes range from 30 thousandths to 1 inch in diameter. While most are round, they can be almost any shape. A square electrode can be used to make holes in solid metal where a square lug is needed to counteract the torque exerted on it. Made of special alloys to resist the heat and thermal shock, the electrodes cost between $3 and $7 an inch. Part of the electrode is disintegrated along with the bolt, drill bit or whatever is being worked on.

Because the coolant flows so voluminously it is necessary to cover the work while the machine is operating. Only that specific area being disintegrated need be covered and the coolant is so effective that after operating for several minutes, he turned the coolant and voltage off and within seconds I felt the end of the electrode and found it cool to the touch, as was the rest of the work.

With all this voltage and coolant being mixed I asked if there was a danger of receiving an electrical shock.

“Oh yeah, in fact I get a constant shock whenever I’m operating the machine. It’s equal to about half of what you’d get by putting a bobbie pin in a wall socket. But I’m used to it and don’t even notice it anymore.”

After scrutinizing the abortion I’d brought him, Jerry selected the appropriate electrode. Then he placed my seemingly tiny engine on the compound of the hungry, metal-eating machine. He aligned my hunk of ailing aluminum so that the center of the broken headbolt was perfectly in line with the hollow molybdenum alloy electrode. He flipped the power switch on; dials and gauges that measured voltages, vibration cycles, and-fluid flows quivered, then steadied. The coolant flowed down the center of the tube. Somewhere from deep within the machine a high pitched hum was emitted and an arc of electricity from the tube began to eat the high speed steel as if it were sucking it up like a straw.

In a few minutes time the only thing left of the E-Z out and the headbolt was the metal left in the grooves of the threads and a rod that fell out the size of the core in the electrode. Pulled with needlenose pliers, the remaining metal in the threads came out like a thin, coil spring, yet the threads themselves were in mint condition. The total cost was $3.