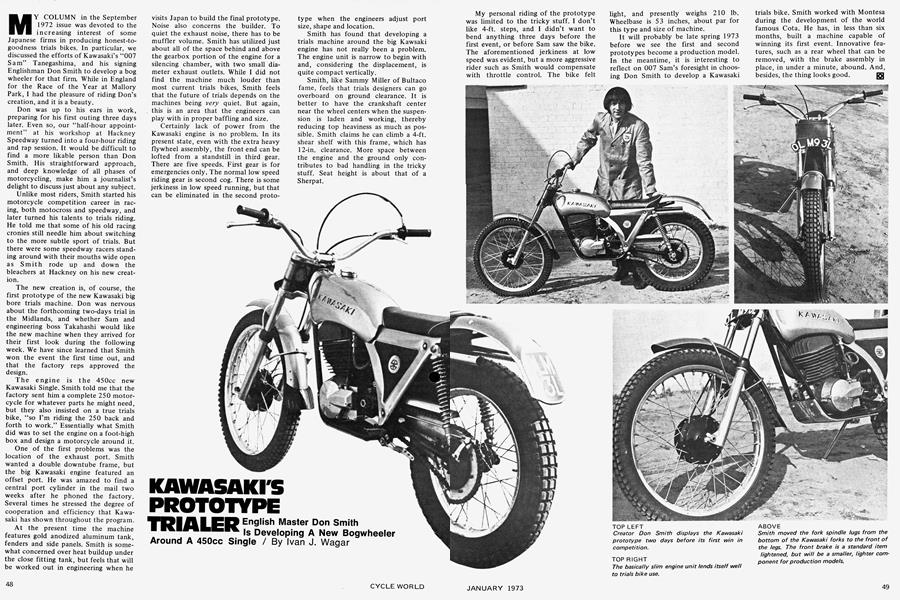

KAWASAKI'S PROTOTYPE TRIALER

English Master Don Smith Is Developing A New Bogwheeler Around A 450cc Single

Ivan J. Wagar

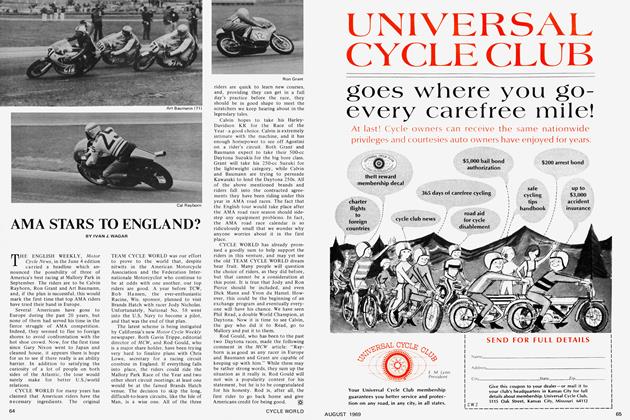

MY COLUMN in the September 1972 issue was devoted to the increasing interest of some Japanese firms in producing honest-to-goodness trials bikes. In particular, we discussed the efforts of Kawasaki’s “007 Sam” Tanegashima, and his signing Englishman Don Smith to develop a bog wheeler for that firm. While in England for the Race of the Year at Mallory Park, I had the pleasure of riding Don’s creation, and it is a beauty.

Don was up to his ears in work, preparing for his first outing three days later. Even so, our “half-hour appointment” at his workshop at Hackney Speedway turned into a four-hour riding and rap session. It would be difficult to find a more likable person than Don Smith. His straightforward approach, and deep knowledge of all phases of motorcycling, make him a journalist’s delight to discuss just about any subject.

Unlike most riders, Smith started his motorcycle competition career in racing, both motocross and speedway, and later turned his talents to trials riding. He told me that some of his old racing cronies still needle him about switching to the more subtle sport of trials. But there were some speedway racers standing around with their mouths wide open as Smith rode up and down the bleachers at Hackney on his new creation.

The new creation is, of course, the first prototype of the new Kawasaki big bore trials machine. Don was nervous about the forthcoming two-days trial in the Midlands, and whether Sam and engineering boss Takahashi would like the new machine when they arrived for their first look during the following week. We have since learned that Smith won the event the first time out, and that the factory reps approved the design.

The engine is the 450cc new Kawasaki Single. Smith told me that the factory sent him a complete 250 motorcycle for whatever parts he might need, but they also insisted on a true trials bike, “so I’m riding the 250 back and forth to work.” Essentially what Smith did was to set the engine on a foot-high box and design a motorcycle around it.

One of the first problems was the location of the exhaust port. Smith wanted a double downtube frame, but the big Kawasaki engine featured an offset port. He was amazed to find a central port cylinder in the mail two weeks after he phoned the factory. Several times he stressed the degree of cooperation and efficiency that Kawasaki has shown throughout the program.

At the present time the machine features gold anodized aluminum tank, fenders and side panels. Smith is somewhat concerned over heat buildup under the close fitting tank, but feels that will be worked out in engineering when he visits Japan to build the final prototype. Noise also concerns the builder. To quiet the exhaust noise, there has to be muffler volume. Smith has utilized just about all of the space behind and above the gearbox portion of the engine for a silencing chamber, with two small diameter exhaust outlets. While I did not find the machine much louder than most current trials bikes, Smith feels that the future of trials depends on the machines being very quiet. But again, this is an area that the engineers can play with in proper baffling and size.

Certainly lack of power from the Kawasaki engine is no problem. In its present state, even with the extra heavy flywheel assembly, the front end can be lofted from a standstill in third gear. There are five speeds. First gear is for emergencies only. The normal low speed riding gear is second cog. There is some jerkiness in low speed running, but that can be eliminated in the second prototype when the engineers adjust port size, shape and location.

Smith has found that developing a trials machine around the big Kawsaki engine has not really been a problem. The engine unit is narrow to begin with and, considering the displacement, is quite compact vertically.

Smith, like Sammy Miller of Bultaco fame, feels that trials designers can go overboard on ground clearance. It is better to have the crankshaft center near the wheel centers when the suspension is laden and working, thereby reducing top heaviness as much as possible. Smith claims he can climb a 4-ft. shear shelf with this frame, which has 12-in. clearance. More space between the engine and the ground only contributes to bad handling in the tricky stuff. Seat height is about that of a Sherpat.

My personal riding of the prototype was limited to the tricky stuff. I don’t like 4-ft. steps, and I didn’t want to bend anything three days before the first event, or before Sam saw the bike. The aforementioned jerkiness at low speed was evident, but a more aggressive rider such as Smith would compensate with throttle control. The bike felt

light, and presently weighs 210 lb. Wheelbase is 53 inches, about par for this type and size of machine.

It will probably be late spring 1973 before we see the first and second prototypes become a production model. In the meantime, it is interesting to reflect on 007 Sam’s foresight in choosing Don Smith to develop a Kawasaki

trials bike. Smith worked with Montesa during the development of the world famous Cota. He has, in less than six months, built a machine capable of winning its first event. Innovative features, such as a rear wheel that can be removed, with the brake assembly in place, in under a minute, abound. And, besides, the thing looks good. IS]