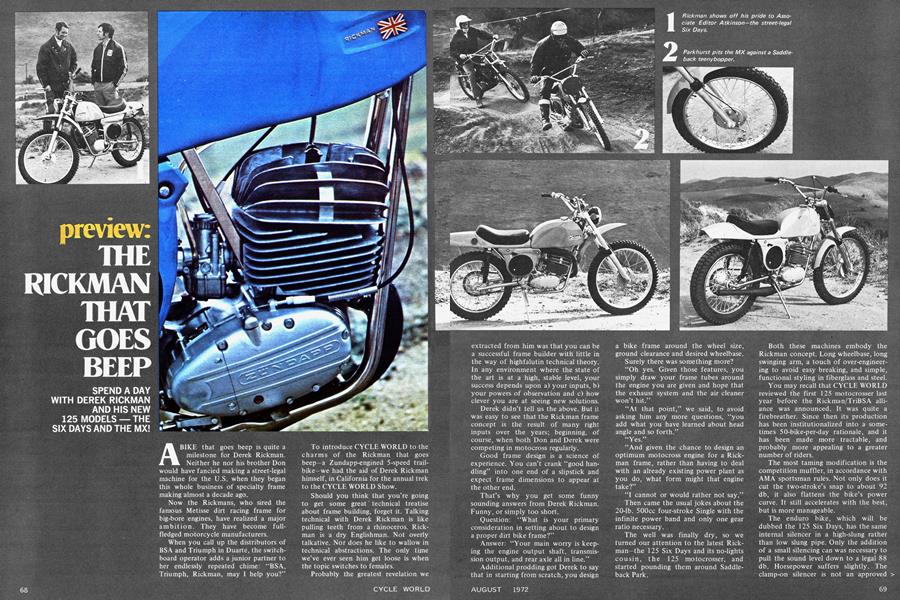

preview: THE RICKMAN THAT GOES BEEP

SPEND A DAY WITH DEREK RICKMAN AND HIS NEW 125 MODELS — THE SIX DAYS AND THE MX!

A BIKE that goes beep is quite a milestone for Derek Rickman. Neither he nor his brother Don would have fancied making a street-legal machine for the U.S. when they began this whole business of specialty frame making almost a decade ago.

Now the Rickmans, who sired the famous Metisse dirt racing frame for big-bore engines, have realized a major ambition. They have become fullfledged motorcycle manufacturers.

When you call up the distributors of BSA and Triumph in Duarte, the switchboard operator adds a junior partner to her endlessly repeated chime: “BSA, Triumph, Rickman, may I help you?” To introduce CYCLE WORLD to the charms of the Rickman that goes beep—a Zundapp-engined 5-speed trailbike—we had the aid of Derek Rickman himself, in California for the annual trek to the CYCLE WORLD Show.

Should you think that you’re going to get some great * technical treatise about frame building, forget it. Talking technical with Derek Rickman is like pulling teeth from a rhinoceros. Rickman is a dry Englishman. Not overly talkative. Nor does he like to wallow in technical abstractions. The only time we’ve ever seen him get loose is when the topic switches to females.

Probably the greatest revelation we extracted from him was that you can be a successful frame builder with little in the way of highfalutin technical theory, in any environment where the state of the art is at a high, stable level, your success depends upon a) your inputs, b) your powers of observation and c) how clever you are at seeing new solutions.

Derek didn’t tell us the above. But it was easy to see that the Rickman frame concept is the result of many right inputs over the years; beginning, of course, when both Don and Derek were competing in motocross regularly.

Good frame design is a science of experience. You can’t crank “good handling” into one end of a slipstick and expect frame dimensions to appear at the other end.

That’s why you get some funny sounding answers from Derek Rickman. Funny, or simply too short.

Question: “What is your primary consideration in setting about to design a proper dirt bike frame?”

Answer: “Your main worry is keeping the engine output shaft, transmission output, and rear axle all in line.” Additional prodding got Derek to say that in starting from scratch, you design a bike frame around the wheel size, ground clearance and desired wheelbase.

Surely there was something more?

“Oh yes. Given those features, you simply draw your frame tubes around the engine you are given and hope that the exhaust system and the air cleaner won’t hit.”

“At that point,” we said, to avoid asking him any more questions, “you add what you have learned about head angle and so forth.”

“Yes.”

“And given the chance to design an optimum motocross engine for a Rickman frame, rather than having to deal with an already existing power plant as you do, what form might that engine take?”

“I cannot or would rather not say.”

Then came the usual jokes about the 20-lb. 500cc four-stroke Single with the infinite power band and only one gear ratio necessary.

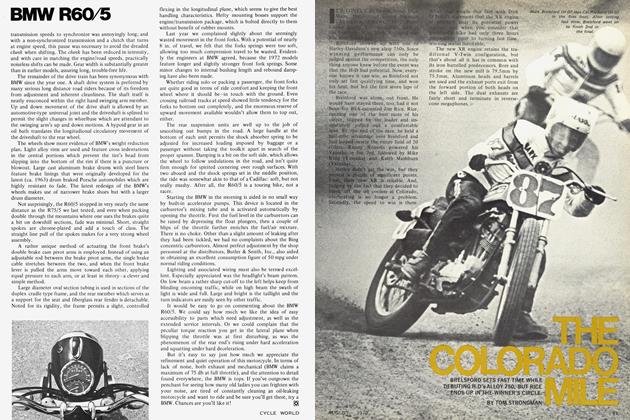

The well was finally dry, so we turned our attention to the latest Rickman—the 125 Six Days and its no-lights cousin, the 125 motocrosser, and started pounding them around Saddleback Park.

Both these machines embody the Rickman concept. Long wheelbase, long swinging arm, a touch of over-engineering to avoid easy breaking, and simple, functional styling in fiberglass and steel.

You may recall that CYCLE WORLD reviewed the first 125 motocrosser last year before the Rickman/TriBSA alliance was announced. It was quite a firebreather. Since then its production has been institutionalized into a sometimes 50-bike-per-day rationale, and it has been made more tractable, and probably more appealing to a greater number of riders.

The most taming modification is the competition muffler, in accordance with AMA sportsman rules. Not only does it cut the two-stroke’s snap to about 92 db, it also flattens the bike’s power curve. It still accelerates with the best, but is more manageable.

The enduro bike, which will be dubbed the 125 Six Days, has the same internal silencer in a high-slung rather than low slung pipe. Only the addition of a small silencing can was necessary to pull the sound level down to a legal 88 db. Horsepower suffers slightly. The clamp-on silencer is not an approved > spark arrester, but is exactly the same size as several approved brands of clamp-on spark arresters. Swapping to meet local requirements will be fairly easy.

The Six Days 125 has a battery, full lighting system, horn, and costs the same as the MX. As both bikes are practically identical, the Six Days is, relatively, a bargain.

Some changes for the worse on both machines: the hand levers are not of the high Magura quality as on the original 125 MX we rode. Further, the “law” has decided, after crash testing a cheapo tank, that all fiberglass tanks are bad, so Rickman has had to go to steel tanks, which are heavy and more easily subject to bending and scratching.

The distributor has had Rickman mount a 3.25/3.50-18 universal tire on the rear of the enduro bike, rather than a full 3.50. “That’s what they want,” shrugged Derek, indicating that he felt it was somewhat small. We thought so, too, for it tends to make the back wheel step sideways too easily, detracting from the machine’s handling.

The MX model retains the fuller 3.50-18 and thus exhibits the bike’s great potential as a controllable slider.

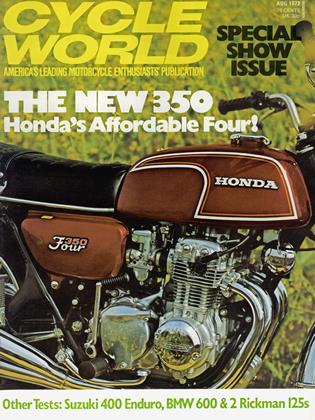

Both Zundapp engines need, and will sustain, considerable buzzing to get the best power from them. A 26mm Bing provides ample throat size for the high rpm these engines will turn. If you make the mistake of trying to let them pull while operating the low to middle rpm band, you’ll find unseemly gearing gap between 2nd and 3rd—particularly so on the enduro bike, which is made more asthmatic by its add-on muffler can.

Measuring the bikes, we found some classic proportions—proportions for full-sized riders. The handlebars are 32 in., the seat height a proper 31 in., and footpeg height 11 in. Ground clearance of the Six Days is 9.5 in., and is reduced to 8.0 in. on the MX model; it looks like you might be using the low-slung MX exhaust for a skid every now and then. The general feeling of both the Rickmans is roomy. The. seats are well padded and comfortably wide. If you are of average height, say from 65 to 72 inches, you’ll find the machines quite comfortable.

“Even though the engines are smaller, there’s a limit to how small the bikes should be,” said Derek. “You have to have a certain amount of machine under you to provide control.”

The wheelbase measurement, at 52.5 in., provide a clue to either Rickman’s stability, for it is as long as some 250s. Suspension has not suffered at all in the change from Ceriani to Betor forks and the mistake has not been made of setting them up too hard. The Betors work easily to the full range (6 in.) of their travel, stopping short of bottoming with a 165-lb. rider aboard. The springs of the Girling rear damper units are single rate 75 lb.

Steering is precise, a product of the 2.75-21 tires on the front of both machines, as well as the tapered roller bearing steering head and the alloy fork clamps, which are set with double Allan screws. Rickman 5.5-in. by 1-in. drums, in lightweight conical hubs, keep the unsprung weight low and the suspension responsive. Swinging arm flex is minimized with the use of Reynolds “531” alloy. The main frames, however, are mild steel, adequate enough in this use.

The enduro bike feels much different in the corners due to the inertia of the headlight, which must swing back and forth with the steering head. Otherwise, there is no difference in geometry between the two machines. Both are pure motocross, double-loop, and neutral handling, as usual. The advantage with these Rickmans is that both are near the 200-lb. mark wet and even easier to throw around than the Montesa-engined 250, or the big-bore frame kit models.

Rickman-125 Six Days & 125 Motocross

$860

Like the MX, the Six Days model has a rubber-bushed swinging arm, which also doubles as a chain adjuster. Rather than loosen the rear axle, you loosen the swinging arm bolt and take up rear chain play with an otherwise conventional locking bolt arrangement.

The enduro model’s speedometer is resettable, but not really enduro worthy. It only resets to zero, which makes it impossible to adjust upward for error compensation. And, as it is driven from the back wheel, its readings are subject to error caused by power-on and power-off wheelspin. Derek said he hopes to have a proper front drive enduro speedometer on the bike soon.

Fortunately, the Rickman concerncomposed of development man Don Rickman, brother Derek in engineering and marketing, Herb Evemy in fiberglass and Ron Baines, commercial operations and general manager, plus 100 employees working in a 40,000-sq. ft. plant—is still small enough at the top and has good enough feedback to incorporate changes in the middle of the model year.

Quite a milestone, the Rickman that beeps. And with 5000 yearly production well on its way (plus new models like a mini-Rickman and bigger than 250cc Rickmans), more people than ever before can have one of these nickel plated beauties. [Oj