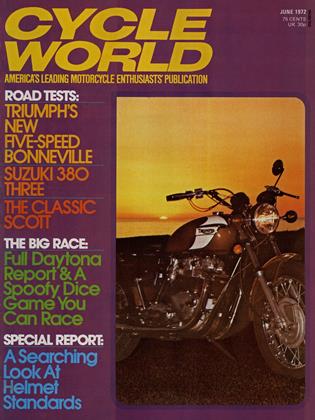

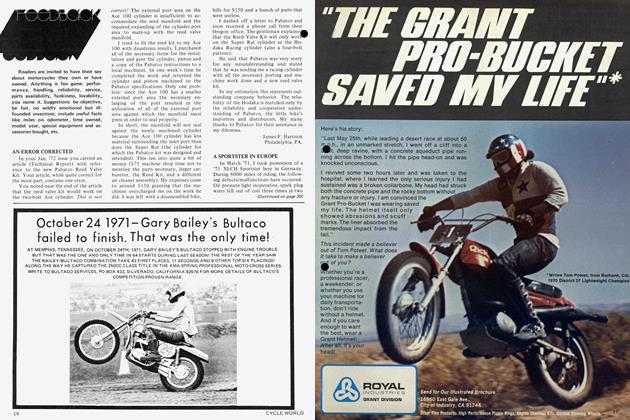

Scott "Flying squirrel"

CLASSIC TEST

One of Today's More Unusual Anachronisms

IT'S ALL TOO seldom that our Classic Tests appear, for it's both thrilling and enlightening to ride and write about the forerunners of today's ultra-sophisticated motorcycles. Many present-day "innovations" are really nothing of the kind; they're merely rehashes of something that appeared many years ago, but of course are improved upon tremendously due to superior materials and manufacturing techniques.

If you haven't read the "History of Scott," by Geoffrey Wood, elsewhere in this issue it would pay you to do so at this time and return to the "Flying Squirrel" test after you've digested it. Being well acquainted with the history of the Scott motorcycle will make this test much more enjoyable and understandable.

With only a dozen or so known Scott owners in the United States at present, we had to look pretty hard to find one who would be willing to let the machine out for a short ride and have it subjected to the CYCLE WORLD scales, rulers and prying camera. Such a person we found through Alan Girdler, executive editor of CW's companion publication, Road & Track.

Toly Arutunoff is a wealthy sports car dealer in Tulsa, Okia., who drives his Morgan in sports car races, chases about all over the European continent buying up exotic automobiles to sell in America, and rides the pride and joy of his motorcycle stable, the Scott "Flying Squirrel," when time permits. Eccentric, you might think, but you wouldn't be sure until you saw him riding (!) his gasoline engine-powered pogo stick through the pits at Sebring!

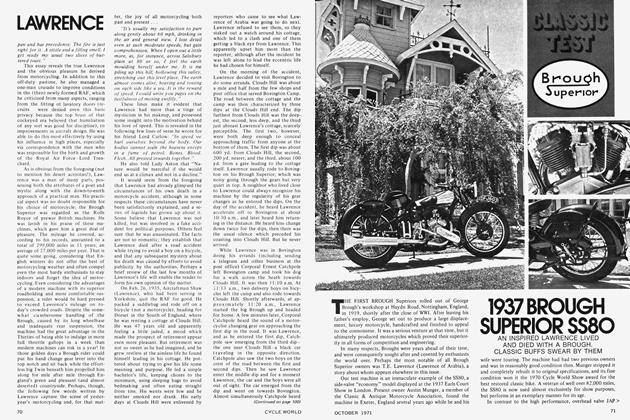

Toly's Flying Squirrel is one of the more recent ones to leave the Shipley works in England. There, fewer than a dozen of these motorcycles are hand-assembled each year and are a strange mixture of the modern and the very old. Taken as a whole, the motorcycle looks very much like a late `40s model. On closer inspection, however, one finds telescopic front forks, a swinging arm frame and a four-shoe front brake! A mind-boggling motorcycle, to say the least.

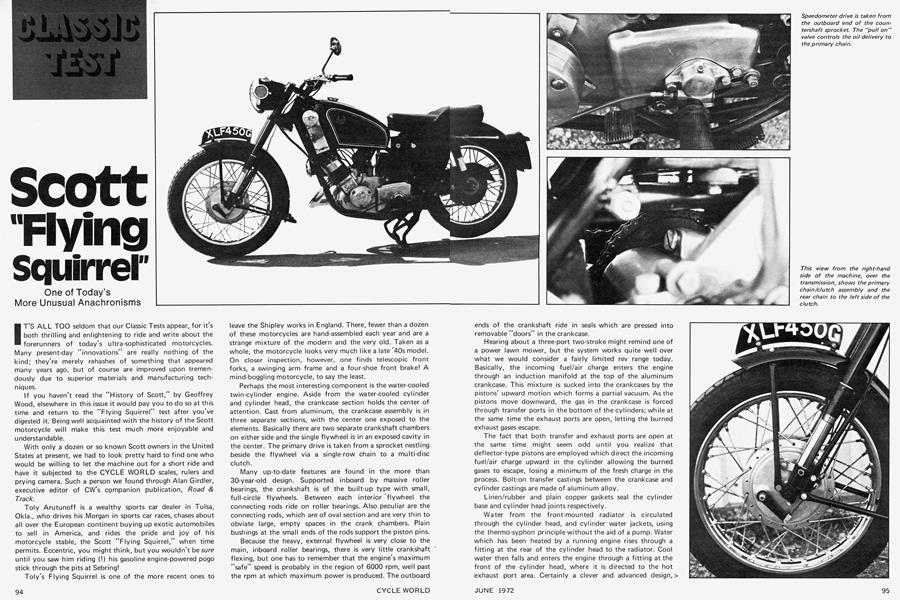

Perhaps the most interesting component is the water-cooled twin-cylinder engine. Aside from the water-cooled cylinder and cylinder head, the crankcase section holds the center of attention. Cast from aluminum, the crankcase assembly is in three separate sections, with the center one exposed to the elements. Basically there are two separate crankshaft chambers on either side and the single flywheel is in an exposed cavity in the center. The primary drive is taken from a sprocket nestling beside the flywheel via a single-row chain to a multi-disc clutch.

Many up-to-date features are found in the more than 30-year-old design. Supported inboard by massive roller bearings, the crankshaft is of the built-up type with small, full-circle flywheels. Between each interior flywheel the connecting rods ride on roller bearings. Also peculiar are the connecting rods, which are of oval section and are very thin to obviate large, empty spaces in the crank chambers. Plain bushings at the small ends of the rods support the piston pins.

Because the heavy, external flywheel is very close to the main, inboard roller bearings, there is very little crankshafi~ flexing, but one has to remember that the engine's maximum "safe" speed is probably in the region of 6000 rpm, well past the rpm at which maximum power is produced. The outboard ends of the crankshaft ride in seals which are pressed into removable "doors" in the crankcase.

Hearing about a three-port two-stroke might remind one of a power lawn mower, but the system works quite well over what we would consider a fairly limited rev range today. Basically, the incoming fuel/air charge enters the engine through an induction manifold at the top of the aluminum crankcase. This mixture is sucked into the crankcases by the pistons' upward motion which forms a partial vacuum. As the pistons move downward, the gas in the crankcase is forced through transfer ports in the bottom of the cylinders; while at the same time the exhaust ports are open, letting the burned exhaust gases escape.

The fact that both transfer and exhaust ports are open at the same time might seem odd until you realize that deflector-type pistons are employed which direct the incoming fuel/air charge upward in the cylinder allowing the burned gases to escape, losing a minimum of the fresh charge in the process. Bolt-on transfer castings between the crankcase and cylinder castings are made of aluminum alloy.

Linen/rubber and plain copper gaskets seal the cylinder base and cylinder head joints respectively.

Water from the front-mounted radiator is circulated through the cylinder head, and cylinder water jackets, using the thermo-syphon principle without the aid of a pump. Water which has been heated by a running engine rises through a fitting at the rear of the cylinder head to the radiator. Cool water then falls and enters the engine through a fitting at the front of the cylinder head, where it is directed to the hot exhaust port area. Certainly a clever and advanced design, particularly for this era of motorcycling development.

A single, duplex Pilgrim pump located outside the door on the right-hand side of the crankcase supplies oil for the engine. A Pilgrim pump is the type which is still employed for the total-loss oiling systems of four-stroke speedway machines. This pump is roughly square in shape, has a glass window on top so that the oil delivery rate can be checked, and has a thumbscrew on either side to vary the oil delivery rate.

Oil delivered to the engine is drawn into the main bearings' cavities and is admitted to the rod bearings by a rotating slotted plate. The slot comes around when the pistons are going up and the vacuum pulls the oil into the rod bearings. Once having lubricated them, it is flung upward to lubricate the wrist pin bearings and cylinder walls, and is then transferred into the combustion chambers and burned along with the fuel/air charge.

Carburetion is handled by an ancient-looking Amal instrument with a bolt-on float bowl. It isn't fitted with an air cleaner, but does have a choke slide to aid starting the engine on cold mornings.

When the left-hand side of the engine is looked at we find an up-to-date piece of equipment—the Lucas 6V alternator assembly, located in an aluminum casting. On the right-hand side is the Lucas automatic advance distributor and a rectifier is visible just above the carburetor inlet bell. The lights, ammeter and switch are supplied by Miller, and a Smiths chrometric speedometer ticks its way up to the attained speed.

The starting drill for the Scott is a process which some of us remember fondly-turn on the fuel tap, prime the carburetor until gas runs out the top of the float chamber, close the choke lever, pull on the tap which controls the flow of oil to the primary chain, turn on the ignition switch and "thrust downward vigorously" on the starter pedal. After a couple of prods, the engine burbles to life and settles down to a slow, even idle after a brief warm-up and opening the choke.

Although the huge central flywheel smooths out the power impulses quite well, the Scott vibrates slightly more than, say, a Suzuki T500, but because of the slower revving engine the vibration isn't as annoying as a modern, high-speed engine's buzz.

Because of the dry clutch's low spring pressure requirement, clutch lever pressure is very low. Gear lever travel is decidedly long by today's standards, but shifting is "soft" and positive, although by no means "slick and crisp." A long gear lever makes it necessary to lift one's foot from the footpeg to accomplish downward changes (the shift pattern is one up, two down), which precludes what we now consider fast shifts. A very close gearset makes slipping the clutch necessary to get underway, especially when starting up a hill. The gearbox is very quiet in operation, however, but the sight of outside control linkages is a rare one indeed.

More up-to-date is the frame/suspension package. Telescopic front forks which claim 6 in. of travel were regrettably very stiff on Toly's bike, but work well when they are right, we understand. The rear suspension units are Girling and work like any modern British machine's units. The frame is of the double cradle design and appears to be well put together, in spite of some less than excellent welding here and there.

Handling qualities, aside from the very stiff fork action, are quite good by modern standards. A long wheelbase of nearly 60 in. and considerable steering rake angle and trail make the Scott steer a trifle on the slow side at low speeds, but the extremely low center of gravity and moderate weight make in-town riding pleasurable. High speed stability couldn't be sampled because of the machine's new engine. The makers recommend a break-in period of more than 1000 miles at a maximum of 35-40 mph and in deference to the machine's newness (?) this staff member didn't try to pretend he was competing in a Classic Machine Race at Snetterton!

Braking, on the other hand, is excellent. Total brake swept area is a generous 85 sq. in., and aside from the fact that the rear brake (which is cable operated) wasn't seating properly, the machine could be slowed from our moderate cruising speeds in a minimum of time. Fade tests weren't possible, but the brakes are above average. With the machine unladen, the brake loading is a low 5 lb./sq. in.!

Riding position is in the British tradition with low handlebars, curved slightly rearward, a fairly low seat and high-mounted footpegs. The dual seat is stepped, the passenger sitting almost two inches higher than the rider. The seat is comfortably shaped, but the padding is distinctly hard.

The Scott is a nostalgic motorcycle which would probably not be enjoyed by many of the younger generation today. It requires quite a bit of maintenance to ensure long life, is decidedly "sluggish" in the performance realm, and it looks "old." However, there are many people all over the world who would like to have a new Scott, if for no other reason than just to have it around as a conversation piece. The dozen or so members of the Scott owners' club here in the United States belong to one of the most enthusiastic, and exclusive, owners' clubs in the world. ®

scott