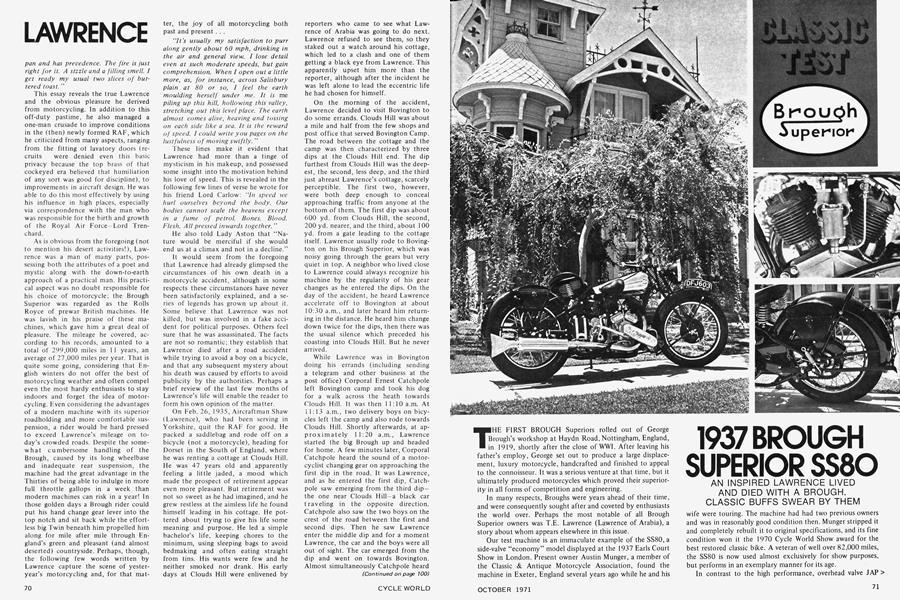

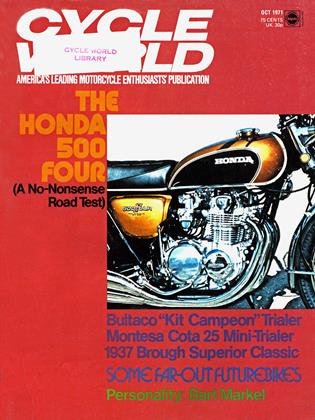

1937 BROUGH SUPERIOR SS80

CLASSIC TEST

Brough Superior

AN INSPIRED LAWRENCE LIVED AND DIED WITH A BROUGH. CLASSIC BUFFS SWEAR BY THEM

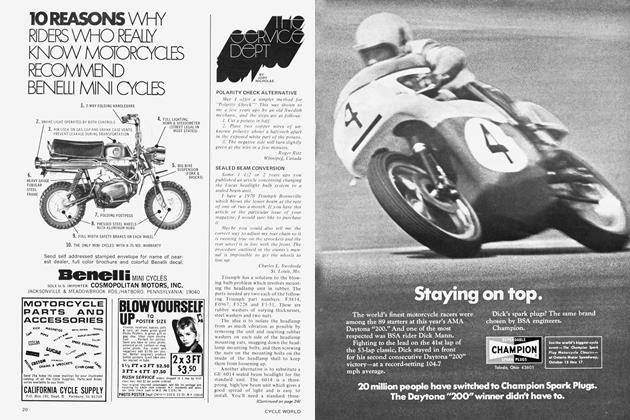

THE FIRST BROUGH Superiors rolled out of George Brough's workshop at Haydn Road, Nottingham, England, in 1919, shortly after the close of WWI. After leaving his father's employ, George set out to produce a large displacement, luxury motorcycle, handcrafted and finished to appeal to the connoisseur. It was a serious venture at that time, but it ultimately produced motorcycles which proved their superiority in all forms of competition and engineering.

In many respects, Broughs were years ahead of their time, and were consequently sought after and coveted by enthusiasts the world over. Perhaps the most notable of all Brough Superior owners was T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), a story about whom appears elsewhere in this issue.

Our test machine is an immaculate example of the SS80, a side-valve “economy” model displayed at the 1937 Earls Court Show in London. Present owner Austin Munger, a member of the Classic & Antique Motorcycle Association, found the machine in Exeter, England several years ago while he and his

wife were touring. The machine had had two previous owners and was in reasonably good condition then. Munger stripped it and completely rebuilt it to original specifications, and its fine condition won it the 1970 Cycle World Show award for the best restored classic bike. A veteran of well over 82,000 miles, the SS80 is now used almost exclusively for show purposes, but performs in an exemplary manner for its age.

In contrast to the high performance, overhead valve JAP> engines of the SS100 models, the SS80 uses the 990-cc Matchless Model “X” engine, a side-valve unit with a low 6:1 compression ratio, “square,” 85.5-mm hore/stroke dimensions, and twin, small-bore Amal carburetors. These engines were very happy running on the low-octane “pool” gasoline in use before WW1I, and were noted for their low speed pulling power, moderate fuel consumption and unfailing reliability.

A forked connecting rod assembly connects the flat-top pistons to an enormously heavy flywheel assembly, and the rods themselves ride on four rows of roller bearings at the crankpin. A triple-row roller bearing supports the crankshaft on the drive side, and a plain bush is used on the timing side. A rather unusual three-lobed camshaft, with four cam followers, is used to control the opening of the valves, which are closed by coil springs. Valve stem lubrication is accomplished externally by Zerk (grease) fittings, while engine lubrication is done by a double-plunger pump which draws its oil from a remote tank.

Starting the big Twin proved to be extremely easy: “tickle” the single float bowl and give the kickstarter a deliberate prod. Retarding the spark isn’t necessary, and the compression release is actually superfluous unless you weigh under 100 lb. or the engine is very cold.

Once running, the SS80 settles down to a fairly rough idle which was caused by worn throttle slides. Nevertheless, pickup is quite good and the engine performs very well under load. Vibration is minimal, and what does come through the handlebars and foot pegs is of such low frequency because of the slow revving engine that it’s not objectionable. Valve noise level is rather high, but is all in keeping with the character of the machine.

The huge, single muffler with aluminum fishtail end cap effectively reduces the exhaust noise, but seems to create too much back pressure for optimum performance. However, George Brough was more than a perfectionist in crafting his motorcycles; he was also a harbinger of the Age of Ecology in that he insisted upon a quiet running motorcycle. Quoting from the SS80’s instruction manual: “Do not race the engine in neutral gear position, violently accelerate from a standstill, or drive at full speed on full throttle, etc., when in a residential district. Any motorcycle (or, for that matter, any motor vehicle) when so driven creates abnormal noise, and in the interests of all motorists I earnestly implore any motorcycle owner to refrain from any of the practices enumerated, or any calculated to cause annoyance to the public in general. Recollect that the degree of silence of your cycle is judged, not by the actual noise it is making, but by comparison to other noises present.”

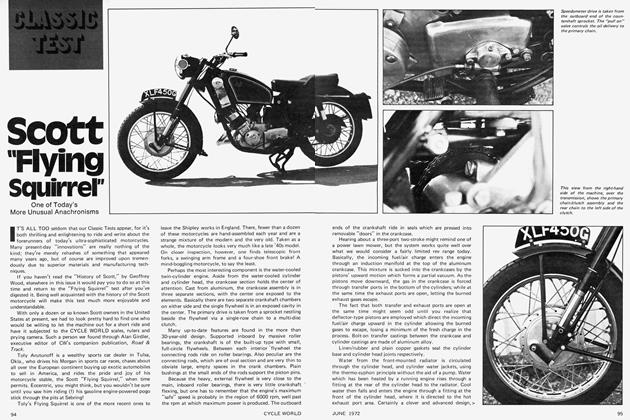

As was Brough’s practice, the transmission (in addition to the engine) was produced by another firm. In this instance, a Norton transmission and clutch is used, and an unusual horizontally split primary chaincase is featured.

Shift lever travel is decidedly long by today’s standards, and gear changing must be done slowly and deliberately. The closeness of the upper three ratios, however, makes shifting a real pleasure. Once underway, low gear is practically unnecessary, as the engine is quite happy pulling from just above idle rpm. Clutch action is very light, but some slippage occurred if the engine and road speeds weren’t matched after a shift, indicating weak clutch springs. With such a wide powerband, a close ratio, four speed transmission is really superfluous, but would be useful if a sidecar were attached.

From the rider’s perch on the wide, comfortably sprung solo saddle, the control layout is quite conventional: rear brake pedal on the left, gear shift lever on the right with a one-up-three-down shift pattern, throttle twistgrip on the right handlebar and the spark advance twistgrip on the left. The carburetor choke control is on the right handlebar and the compression release lever (which is as large as a clutch lever) is mounted on the left. Clutch and front brake levers are in their respective positions, but are mounted in the manner common in that era—they pivot from the ends of the handlebars. This type of arrangement requires the cables to run inside the handlebars, making for a much cleaner appearance. The levers are quite odd looking, but feel like the more conventional levers on today’s motorcycles. A horn button and a light switch mounted in the 8-in. headlamp complete the control group, and a Smith’s chronométrie speedometer, which is driven by the rear wheel, nestles in front of the steering damper knob.

Even though the front brake drum measures nearly 7 in. in diameter, the stopping power delivered is quite poor by today’s standards. Squeezing the lever back against the handlebar provides some degree of retardation, but not nearly enough for a motorcycle weighing over 450 lb. The rear brake, on the other hand, is very powerful and requires only moderate pedal pressure to lock the rear wheel. It is also quite resistant to fade, but the overall brake rating is, at best, only poor to fair.

Large capacity roadburners of the Thirties almost always featured long wheelbases and rigid rear frame sections. The SS80 is no exception. A nominal wheelbase measurement of 60 in. and what felt like a large amount of steering trail produces a machine which tends to be “happiest” running at speed down a straight road. Only tiny corrections at low to moderate speeds tend to make the machine “straighten up,” whereas much less finesse is required to keep it tracking true at highway speeds. Out of curiosity, we measured the trail and found it to be in the neighborhood of 2 in., which leads us to think that the rather odd handling qualities at low speeds are mostly caused by the “highish” center of gravity and not from a large trail measurement.

Generous travel is provided by Brough girder-style front forks, which have an adjustable friction damper that can be reset while the rider is sitting in the saddle. This is in addition to the normal steering damper located on the top fork yoke, which needed to be tightened slightly while riding on rough roads. Once the handling characteristics had been figured out, the SS80 could be ridden quite fast over poorly surfaced roads with complete confidence. Not having any rear suspension took some getting used to, but the combination of the very good fork action and the softly-sprung solo saddle contributed a great deal to rider comfort. Pillion footrests are provided and fold rearward, instead of upward, and almost all the later Broughs were equipped with panniers (saddlebags), but no rear seat.

Deeply valanced fenders provide the rider with excellent protection from wet streets, and the rear chain’s top and bottom runs are protected by their own guards. The wide gas tank is unmistakably Brough in design, featuring two filler caps and a 4-gal.-plus capacity. There is no reason to doubt that the Brough’s original finish wasn’t as excellent as this one, with fanatical attention to detailing all metal castings and welds, as well as lavishly applied chrome plating and paintwork.

The frame’s single cradle design isn’t too interesting, but the methods and materials used to assemble it certainly are. All lug castings are ground perfectly smooth, tapered, and then fishtailed to provide maximum strength where they are brazed to the frame tubes, by allowing a generous amount of brass to flow around and into the joint. Even the lugs which are partially hidden by the motor mount plates have received this treatment, as have the sidecar attachment lugs. Large diameter, thin-walled tubing is used where practical, making the frame almost immune to flexing in the wrong places.

A Lucas Magdyno (a six-volt generator sitting on top of a manual-advance magneto) is located in front ol the engine and is driven by a single-row chain. A highly polished aluminum shroud protects the unit from water and dirt thrown up by the front wheel and enhances the appearance of the machine. Even by today’s standards, the lighting is quite good with the exception of the small stop light/taillight assembly. The 8-in. headlamp, with vertical lens segments, throws a wide beam down the road at night, a feature necessary in the days of sparsely traveled roads and poor street lighting. A Lucas horn completes the electrical group.

In addition to the rear stand, a Karslake-Brough sidestand is fitted. This “kickstand” is mounted under the left-hand footrest and pivots from the outer edge of the footrest inward, up and out of the way. Of course, a prerequisite for mounting the prop stand there is that the footrest be strong enough to support the weight of the machine. No problem with the Brough, which is as sturdy as it is handsome.

Shortly before WWII, George Brough began production of his automobile, which possessed the excellence of his high quality motorcycles. As soon as war was declared, however, the entire efforts of the factory were turned over to producing high precision engineering parts for the now legendary Spitfires and Lancasters of the Royal Air Force.

After the war, steel and other raw materials were so strictly rationed that George decided not to reenter the vehicle manufacturing field. Instead, his firm continued its wartime specialization of precision engineering work, and today employs 150 people.

Some 400 members of the Brough Superior Club keep track of, log and have spare parts made for their beloved Broughs, machines which occupy a special niche in the history ol motorcycling.

BROUGH SUPERIOR SS80

View Full Issue

View Full Issue