It's a Steal

JOSEPH E. BLOGGS

"...your chances of getting a stolen bike back are about one in four."

THE THIEF WHO BROKE into a motorcycle salesroom in Manhattan, Kansas, and cut out on one of the bikes, was soon caught by the police. His excuse has become a classic: ”I guess I'm a cyclepath," he said. The unintended pun caused smiles, but the business of motorcycle theft stopped being funny a long time ago.

+ + +

In the United States, 150 motorcycles are stolen every day. The California Highway Patrol says that 10,000 will be stolen in the Golden State this year alone. Theft of all vehicles is up by 20 percent according to a GM survey conducted last year in the eastern United States. But piracy on cars with the triple-lock system —ignition, steering and transmission—is down 27 percent, says Donald P. Marquis of GM's Saginaw Steering Gear Division. The answer to the conflicting statistics would seem to be that older cars and motorcycles have been added to the shopping lists of thieves who formerly concentrated on late model automobiles.

A recent dealer meeting in Texas was told that an increasing number of insurance companies are refusing to write theft policies for motorcycles. Worse than this, many are turning down renewal of existing contracts. What this means to the dealers—and more importantly, to you —is that you'll have a harder time buying a bike. In fact, you might have to dig up cash for your next machine. The reason for this is that finance companies usually require reasonable coverage before they stamp approval on a deal. No insurance - No deal.

The National Auto Theft Bureau and police department blame dealers for inaccurate registration and vague records of sales leading to the sudden and alarming increases in motorcycle theft. The dealers point the finger at manufacturers for the confusing profusion of numbers scattered all over the frames and engines of bikes, and at you for not taking reasonable precautions to foil the rip-off artist. And all the argument is pointless. It couldn't matter less who is to blame, but what is important is what can be done about it.

That there is a problem is quite evident. Known heavy loss areas for motorcycle theft are Nebraska, Texas and Georgia. The loss rate in Massachusetts and New Jersey is around 200 percent. This means that for every $100 in premiums collected by insurance companies, they pay out $200. Not even government can stand that sort of business.

Depending on where you live, your chances of getting a stolen bike back are one in four. And if your hack is lifted, and the police get it back, you still may never see it again. The reason is that as many as 25 percent of all motorcycles are incorrectly registered. So if it s picked up by police and the engine or frame numbers don't match your title, you may never hear of it being recovered. And even if you do, you'll need pretty conclusive proof of ownership. If someone made an error in your documents, your stolen motorcycle could rust away in some police impound garage, even if you know it's there! However, if you know how these hijackers operate, you might be able to lock the stable door before someone rustles your horse.

+ + +

Thieves come in all shapes and sizes, and the motorcycle specialist is no exception. It is generally accepted by law enforcement agencies that one in about 200 youngsters starts off a life of crime by stealing a vehicle; that if he does, it's nine to one that he II become a hardened criminal; and if he sticks to vehicle theft, he can reckon on stashing away $1,000,000 of merchandise before he spends one year in jail.

The young Dillinger usually starts by swiping a bike for excitement, the envy of his friends and free transportation for the evening. The red line on your tach doesn't exist for him, and he'll drag anything in sight. Although the chances of being caught are slim, if he does become involved in a police chase you've usually got a couple of basket cases—bike and operator.

If he gets away with a number of successful heists, he'll graduate to stealing bikes to strip: hence, the term, rip-off artist. He'll either sell the parts or use them for his own motorcycle. Sooner or later, he joins a gang. This may be an off-shoot of one of the outlaw clubs, or it could be a professional ring. The unwashed outfits range over a radius of about 300 miles, moving to a locality for a few days, cleaning up and then moving on. They send the most respectable member to answer newspaper ads for the models they're interested in. When a likely hit is found, the gang will steal the motorcycle, and move it to their home base as quickly as possible, usually the same night. The bike is often fitted with cold plates belonging to a gang-member with a legally registered cycle. They move fast, and can often rack up one hit a night. The motorcycles they accumulate are mostly cannibalized for parts, and either sold to chopper builders or fly-by-night repair operations.

When it comes to organization, the professional gang makes a military operation look like an Irish wake. They employ spotters, look-outs, pick-up men, welders, paint specialists, mechanics and forgers. The friendly little tad who delivers your daily paper could be a top spotter. His job is to find likely hits, and to pass the information on by phone. He's usually interested in specific models, year of manufacture, condition, security details and the habits of your family. For a successful heist, he's paid $10. No risk, and when he gets greedier or more ambitious, it's just a short step to the big-time.

Look-outs watch for police or possible trouble, while the pick-up man actually makes the snatch. He can do this by driving the bike away or by winching it into the back of a pick-up truck in seconds.

Locks can be neutralized by a case-hardened screw and a slide hammer, and even burglar alarms can be shorted out or opened similarly to a lock, and shorted electrically after the alarm has sounded. But in a recent editorial in Motorcycle Dealer News, Paul Ditzel points out that the big weakness is in ignition and steering locking systems. It seems that Lieutenant George F. Hees of the Los Angeles Police Department's Burglary-Auto Theft Division recently walked into a dealer's and bought a key for his son's motorcycle. Lieutenant Hees, a nationally recognized authority on vehicle theft, had only to give the serial number of the motorcycle and pay 50 cents for a duplicate ignition key. As Mr. Ditzel points out, four bits a heist is not a bad investment.

Once the snatch has been made, the stolen bike usually ends up in an underground workshop, where numbers are altered. An acid test can detect number changes, so the latest wrinkle is to drill out the old numbers, fill in the holes by hel ¡arcing, dress the surface and stamp new numbers. These can match forged titles, or can be made up to suit the papers for wrecked or junked bikes. Some outfits offer up to $100 for a title to someone who has wrecked a bike or had one stolen. The kicker is that the title of a stolen machine might just end up with the original motorcycle—with minor changes. Sometimes titles bought from a junk-yard come complete with engine plates. But however the looters get around the problem, the key to the disposal of a stolen motorcycle seems to lie in the numbering system.

+ + +

When you're talking vehicles, VIN is not a French alcoholic beverage—it stands for Vehicle Identification Number. The motorcycle VIN as defined by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in Washington, and by their opposite numbers in Canada, is the frame number. And this is the basic identity feature accepted by most North American motor vehicle licensing agencies. It's a straightforward six to 12 digit number, usually, hut not always, stamped on the fork-head of your bike. Quite simple, really.

At least, it should be simple, but it's not. You see, you have an engine number as well, and you may also find you have part numbers, foundry casting numbers, production numbers, batch numbers and series numbers. The average motorcycle is a numerologist's nightmare, and a California dealer recently gave mistaken registration numbers for 250 motorcycles. It was a genuine mistake, but the penalty imposed by the authorities at three bucks a throw amounted to $750. Fortunately, the owners were glad to repay the dealer, and that says a lot for a good dealer-customer relationship.

Quite apart from the profusion of numbers leading to more arguments than you'll get at a Security Council meeting at the UN, there's worse to come. With about 12 digits, it's easy to make a mistake. Imagine some poor steno torn between going maxi or buying that new hot pants outfit, and frantically typing page after page of numbers.

Think about how many times the identification number is copied or retyped while you hold the ownership title, let alone the number of times this happened before you bought the bike. Is it surprising that 26 percent of all motorcycles are incorrectly registered?

Then there's the dummy who deliberately gives the wrong number. A police officer in a vehicle theft squad told me about standing behind two characters in a lineup at a Canadian licensing bureau. The VIN was not on the bill of sale, and when the clerk asked for it, the owner glibly reeled off a twelve-digit number. The clerk moved away to have the papers typed out, and the owner's companion said, "Jeez, how can you remember a long number like that?"

"I can't," the owner said, "But that's close enough for a civil servant." They yukked it up for a while, and when my informant made himself known to them, and quietly insisted that they withdraw the VIN at the expense of a phone call to the dealers, there was consternation. Not to mention veiled mutterings about police harassment, and "why ain't you out catching real criminals?"

There is hope, though. In Pennsylvania, the dealer must send an exact reproduction of the VIN to the motor vehicle department. This is done by holding a piece of paper over the number and rubbing it with a pencil. This ensures two things. First, the exact number is faithfully reproduced; and second, even if the number is altered by a rip-off artist, it's relatively easy to compare the renumber job with the suspected original record.

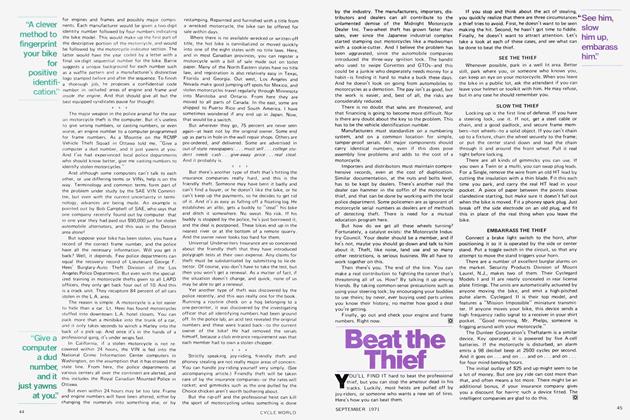

Incidentally, you can "fingerprint" your motorcycle by this method. Pick a location on the engine or frame, and if there is no pattern on the metal, make a few inconspicuous marks with a small file. Then place a piece of paper over this, rub it with a soft pencil and record the exact location in one corner. File this between two pieces of tissue with your other documents, and voila—positive identification.

The problem is being tackled seriously by the Society of Automotive Engineers and the National Auto Theft Bureau. The SAE has formed a Committee on Vehicle Security chaired by Don Wolfslayer, perhaps a prophetic name. Members include Detective Sergeant Don Pohl of the Detroit Police Department; Jim Doto, Product Security of GM Engineering Staff; Bob Campbell of NATB and Joe Devyak of Ford's Product Development Group. The aim of the committee is to investigate all aspects of vehicle theft, and to attempt to suggest improved vehicle security systems and devices.

Eugene J. Halm, the Pacific Coast Division Manager of the NATB, wants to see better industry and distributor records. Robert Barrie, West Coast Special Agent for NATB, goes even further. Barrie, an acknowledged expert in the field, proposed a completely new system of identification for motorcycles, and maintains this will reduce the big steal by 80 percent. Briefly, this would entail identical numbers for engines and frames and possibly major components. Each manufacturer would be given a two-digit identity number followed by four numbers indicating the bike model. This would make up the first part of the descriptive portion of the motorcycle, and would be followed by the motorcycle indicator section. The latter would have the year coded by a letter with a final six-digit sequential number for the bike. Barrie suggests a unique background for each number such as a waffle pattern and a manufacturer's distinctive logo stamped before and after the sequence. To finish a thorough job, he proposes a confidential code number in secluded areas of engine and frame and inside the engine. And that should give all but the best equipped syndicates pause for thought.

“..four bits a heist is not a bad investment!’

"Is it surprising that 26 percent of all motorcycles are incorrectly registered?”

“A clever method to fingerprint your bike for positive identification.”

“Give a computer a dud number, and it just yawns at you!’

+ + +

The major weapon in the police arsenal for the war on motorcycle theft is the computer. But it's useless to give wrong numbers, or casting numbers, or even worse, an engine number to a computer programmed for frame numbers. As a Mountie on the RCMP Vehicle Theft Squad in Ottawa told me, "Give a computer a dud number, and it just yawns at you. And I've had experienced local police departments who should know better, give me casting numbers to identify stolen motorcycles."

And although some computers can't talk to each other, or use differing terms or VINs, help is on the way. Terminology and common terms form part of the problem under study by the SAE VIN Committee, but even with the current uncertainty in terminology, advances are being made. An example is pointed out by Bob Campbell of SAE, who says that one company recently found out by computer that in one year they had paid out $90,000 just for stolen automobile alternators, and this was in the Detroit area alone!

But suppose your bike has been stolen, you have a record of the correct frame number, and the police have all the necessary information. Will you get it back? Well, it depends. Few police departments can equal the recovery record of Lieutenant George F. Hees' Burglary-Auto Theft Division of the Los Angeles Police Department. But even with the specialized training in motorcycle thefts given to all LAPD officers, they only get back four out of 10. And this is a crack unit. They recapture 84 percent of all cars stolen in the L.A. area.

The reason is simple. A motorcycle is a lot easier to hide than a car. Lt. Hees has found motorcycles stuffed into downtown L.A. hotel closets. You can pack more than a minibike into the trunk of a car, and it only takes seconds to winch a Harley into the back of a pick-up. And once it's in the hands of a professional gang, it's under wraps fast.

In California, if a stolen motorcycle is not recovered within 24 hours, the VIN is fed into the National Crime Information Center computers in Washington, on the assumption that it has crossed the state line. From here, the police departments at various centers all over the continent are alerted, and this includes the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Ottawa.

But even within 24 hours may be too late. Frame and engine numbers will have been altered, either by changing the numerals into something else, or by

restamping. Repainted and furnished with a title from a wrecked motorcycle, the bike can be offered for sale within days.

Where there is no available wrecked or written-off title, the hot bike is cannibalized or moved quickly into one of the eight states with no title laws. Here, and in most Canadian provinces, you can register a motorcycle with a bill of sale made out on toilet paper. Many of the North Eastern states have no title law, and registration is also relatively easy in Texas, Florida and Georgia. Out west, Los Angeles and Nevada make good jumping-off spots for Mexico, and stolen motorcycles travel regularly through Minnesota into Manitoba and Ontario. From here they are moved to all parts of Canada. In the east, some are shipped to Puerto Rico and South America. I have sometimes wondered if any end up in Japan. Now, that would be a switch.

But wherever they go, 75 percent are never seen again—at least not by the original owner. Some end up as parts in hole-in-the-wall repair shops. Others are pre-ordered, and delivered. Some are advertised in out-of-state newspapers: . . . must sell. . . college student needs cash . . . give-away price . . . real steal. And it probably is.

+ + +

But there's another type of theft that's hitting the insurance companies really hard, and this is the friendly theft. Someone may have bent it badly and can't find a buyer, or he doesn't like the bike, or he can't keep up the payments, so he decides to get rid of it. And it's as easy as falling off a floating log. He establishes an alibi, gets a buddy to "steal" his bike and ditch it somewhere. No sweat. No risk. If his buddy is stopped by the police, he's just borrowed it, and the deal is postponed. These bikes end up in the nearest river or at the bottom of a remote quarry. And the owner never looks too hard for them.

Universal Underwriters Insurance are so concerned about the friendly theft that they have introduced polygraph tests at their own expense. Any claims for theft must be substantiated by submitting to lie-detector. Of course, you don't have to take the test, but then you won't get a renewal. As a matter of fact, if the situation doesn't change, and quick, none of us may be able to get a renewal.

Yet another type of theft was discovered by the police recently,and this was really one for the book. Running a routine check on a hog belonging to a one percenter, it was discovered by the investigating officer that all identifying numbers had been ground off. In the police lab, an acid test revealed the original numbers and these were traced back-to the current owner of the bike! He had removed the serials himself, because a club entrance requirement was that each member had to own a stolen chopper.

+ + +

Strictly speaking, joy-riding, friendly theft and phoney stealing are not really major areas of concern. You can handle joy-riding yourself very simply. (See accompanying article.) Friendly theft will be taken care of by the insurance companies—or the rates will rocket; and gimmicks such as the one pulled by the Choice chicken aren't worth bothering about.

But the rip-off and the professional heist can kill the sport of motorcycling unless something is done by the industry. The manufacturers, importers, distributors and dealers can all contribute to the unlamented demise of the Midnight Motorcycle Dealer Inc. Two-wheel theft has grown faster than sales, ever since the Japanese industrial complex started stamping out motorcycles like a madwoman with a cookie-cutter. And I believe the problem has been aggravated, since the automobile companies introduced the three-way ignition lock. The bandit who used to swipe Corvettes and GTOs—and this could be a junkie who desperately needs money for a habit—is finding it hard to make a buck these days. And he doesn't look on going from automobiles to motorcycles as a demotion. The pay isn't as good, but the work is easier, and, best of all, the risks are considerably reduced.

There is no doubt that sales are threatened, and that financing is going to become more difficult. Nor is there any doubt about the key to the problem. This has to be the vehicle identification numbèr.

Manufacturers must standardize on a numbering system, and on a common location for simple, tamper-proof serials. All major components should carry identical numbers, even if this does pose assembly line problems and adds to the cost of a motorcycle.

Importers and distributors must maintain comprehensive records, even at the cost of duplication. Similar documentation, at the nuts and bolts level, has to be kept by dealers. There's another nail the dealer can hammer in the coffin of the motorcycle thief, and that can be done by working with the local police department. Some policemen are as ignorant of motorcycle serial numbers as dealers are of methods of detecting theft. There is need for a mutual education program here.

But how do we get all these wheels turning? Fortunately, a catalyst exists: the Motorcycle Industry Council. Your dealer should be a member, and if he's not, maybe you should go down and talk to him about it. Theft, like noise, land use and so many other restrictions, is serious business. We all have to work together on this.

Then there's you. The end of the line. You can make a real contribution to fighting the cancer that's threatening all of us. How? By talking it up among friends. By taking common-sense precautions such as using your steering lock; by encouraging your buddies to use theirs; by never, ever buying used parts unless you know their history, no matter how good a deal you're getting.

Finally, go out and check your engine and frame numbers. Right now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue