FEEDBACK

Readers are invited to have their say about motorcycles they own or have owned. Anything is fair game: performance, handling, reliability, service, parts availability, funkiness, lovability, you name it. Suggestions: be objective, be fair, no wildly emotional but ill-founded invectives; include useful facts like miles on odometer, time owned, model year, special equipment and accessories bought, etc.

A GROUP "TEST"

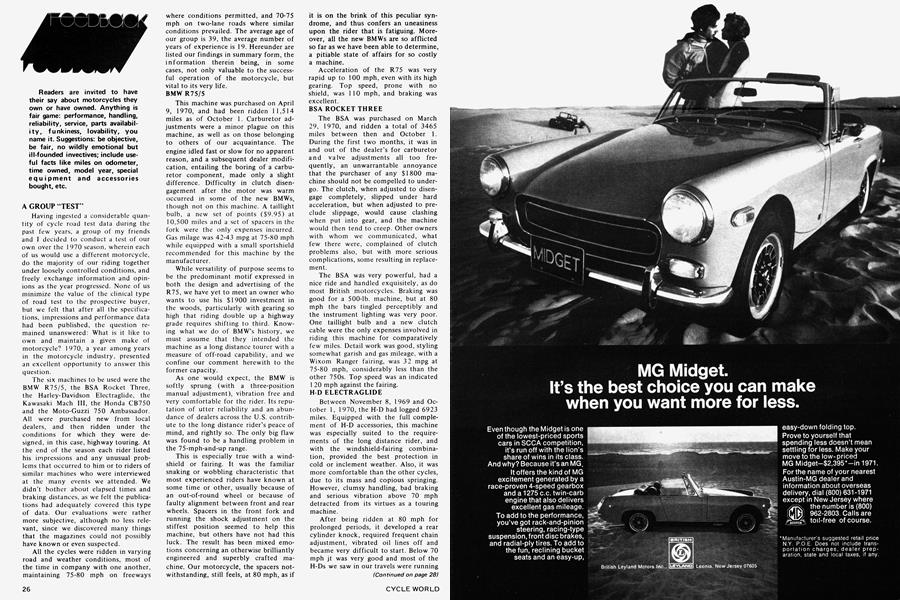

Having ingested a considerable quantity of cycle road test data during the past few years, a group of my friends and I decided to conduct a test of our own over the 1970 season, wherein each of us would use a different motorcycle, do the majority of our riding together under loosely controlled conditions, and freely exchange information and opinions as the year progressed. None of us minimize the value of the clinical type of road test to the prospective buyer, but we felt that after all the specifications, impressions and performance data had been published, the question remained unanswered: What is it like to own and maintain a given make of motorcycle? 1970, a year among years in the motorcycle industry, presented an excellent opportunity to answer this question.

The six machines to be used were the BMW R75/5, the BSA Rocket Three, the Harley-Davidson Electraglide, the Kawasaki Mach III, the Honda CB750 and the Moto-Guzzi 750 Ambassador. All were purchased new from local dealers, and then ridden under the conditions for which they were designed, in this case, highway touring. At the end of the season each rider listed his impressions and any unusual problems that occurred to him or to riders of similar machines who were interviewed at the many events we attended. We didn’t bother about elapsed times and braking distances, as we felt the publications had adequately covered this type of data. Our evaluations were rather more subjective, although no less relevant, since we discovered many things that the magazines could not possibly have known or even suspected.

All the cycles were ridden in varying road and weather conditions, most of the time in company with one another, maintaining 75-80 mph on freeways where conditions permitted, and 70-75 mph on two-lane roads where similar conditions prevailed. The average age of our group is 39, the average number of years of experience is 19. Hereunder are listed our findings in summary form, the information therein being, in some cases, not only valuable to the successful operation of the motorcycle, but vital to its very life.

BMW R75/5

This machine was purchased on April 9, 1970, and had been ridden 11,514 miles as of October 1. Carburetor adjustments were a minor plague on this machine, as well as on those belonging to others of our acquaintance. The engine idled fast or slow for no apparent reason, and a subsequent dealer modification, entailing the boring of a carburetor component, made only a slight difference. Difficulty in clutch disengagement after the motor was warm occurred in some of the new BMWs, though not on this machine. A taillight bulb, a new set of points ($9.95) at 10,500 miles and a set of spacers in the fork were the only expenses incurred. Gas milage was 42-43 mpg at 75-80 mph while equipped with a small sportshield recommended for this machine by the manufacturer.

While versatility of purpose seems to be the predominant motif expressed in both the design and advertising of the R75, we have yet to meet an owner who wants to use his $1900 investment in the woods, particularly with gearing so high that riding double up a highway grade requires shifting to third. Knowing what we do of BMW’s history, we must assume that they intended the machine as a long distance tourer with a measure of off-road capability, and we confine our comment herewith to the former capacity.

As one would expect, the BMW is softly sprung (with a three-position manual adjustment), vibration free and very comfortable for the rider. Its reputation of utter reliability and an abundance of dealers across the U.S. contribute to the long distance rider’s peace of mind, and rightly so. The only big flaw was found to be a handling problem in the 75-mph-and-up range.

This is especially true with a windshield or fairing. It was the familiar snaking or wobbling characteristic that most experienced riders have known at some time or other, usually because of an out-of-round wheel or because of faulty alignment between front and rear wheels. Spacers in the front fork and running the shock adjustment on the stiffest position seemed to help this machine, but others have not had this luck. The result has been mixed emotions concerning an otherwise brilliantly engineered and superbly crafted machine. Our motorcycle, the spacers notwithstanding, still feels, at 80 mph, as if it is on the brink of this peculiar syndrome, and thus confers an uneasiness upon the rider that is fatiguing. Moreover, all the new BMWs are so afflicted so far as we have been able to determine, a pitiable state of affairs for so costly a machine.

Acceleration of the R75 was very rapid up to 100 mph, even with its high gearing. Top speed, prone with no shield, was 110 mph, and braking was excellent.

BSA ROCKET THREE

The BSA was purchased on March 29, 1970, and ridden a total of 3465 miles between then and October 1. During the first two months, it was in and out of the dealer’s for carburetor and valve adjustments all too frequently, an unwarrantable annoyance that the purchaser of any $1800 machine should not be compelled to undergo. The clutch, when adjusted to disengage completely, slipped under hard acceleration, but when adjusted to preclude slippage, would cause clashing when put into gear, and the machine would then tend to creep. Other owners with whom we communicated, what few there were, complained of clutch problems also, but with more serious complications, some resulting in replacement.

The BSA was very powerful, had a nice ride and handled exquisitely, as do most British motorcycles. Braking was good for a 500-lb. machine, but at 80 mph the bars tingled perceptibly and the instrument lighting was very poor. One taillight bulb and a new clutch cable were the only expenses involved in riding this machine for comparatively few miles. Detail work was good, styling somewhat garish and gas mileage, with a Wixom Ranger fairing, was 32 mpg at 75-80 mph, considerably less than the other 750s. Top speed was an indicated 1 20 mph against the fairing.

H-D ELECTRAGLIDE

Between November 8, 1969 and October 1, 1970, the H-D had logged 6923 miles. Equipped with the full complement of H-D accessories, this machine was especially suited to the requirements of the long distance rider, and with the windshield-fairing combination, provided the best protection in cold or inclement weather. Also, it was more comfortable than the other cycles, due to its mass and copious springing. However, clumsy handling, bad braking and serious vibration above 70 mph detracted from its virtues as a touring machine.

After being ridden at 80 mph for prolonged periods, it developed a rear cylinder knock, required frequent chain adjustment, vibrated oil lines off and became very difficult to start. Below 70 mph jt was very good and most of the H-Ds we saw in our travels were running at this speed. The attractive features of the H-D are its capacity to carry equipment, the aforementioned comfort, and unlimited line of accessories and a good dealer network throughout the U.S. The high speed vibration is probably incurable, but the starting trouble is most likely ascribable to the Tillotson carburetor, which has been the subject of much criticism since it was introduced in 1966. Gas mileage on the H-D was 32-35 mpg at 75-80 mph and top speed was an indicated 95 mph with the shield.

(Continued on page 28)

Continued from page 26

HONDA CB750

The Honda covered 6848 miles between May 22, 1970 and October 1. In both appearance and performance the Honda was a pleasure to own and ride. Its handling, braking and in-line stability surpassed anyone’s expectations for a 500-lb. motorcycle, and it was capable of going through the gears side by side with the Kawasaki, a manifest testimony to the power it produces. While smooth at any speed, it produced a surfeit of torque whether it was downshifted or not. The finish was superb, all instruments were readable in light or darkness and its die-cast components were outstanding. The saddle was very comfortable, but the suspension was inordinately stiff and caused a harsh ride compared to any of the other machines. Tuneups seemed to be needed frequently if the machine was to be kept at its optimum and constant attention to the chain was necessary if any life at all was desired. High speeds on freeways are extremely hard on chains and some extraneous form of lubrication is required on the Honda every 300 miles or so because the self-oiling system is inadequate. Even so the chain wore rather quickly. The chain was finally replaced by the dealer, but the general consensus is that an American Diamond brand would be a better substitution at the outset. Expenses on the Honda consisted of four seal-beams (SAE type), a set of points and the discounted chain. Gas mileage was 43-46 mpg at 75-80 mph, and the top speed was 1 18 mph with a Bates Sportshield.

KAWASAKI MACH III

The Kawasaki was purchased on May 22, 1970, and ridden 7974 miles as of October 1. Though not designed as a long distance tourer, the Kawasaki Mach III is a very good compromise vehicle, especially because of its low price.

The ride is very smooth for a 390-lb. motorcycle, and its overall comfort is acceptable, though there is some high frequency vibration in the bars. The long travel in the front fork is an inconspicuous safety feature if the ma-

chine happens to be ridden head-on into a curb or other such obstruction, as one of our riders found out. The engine has a very narrow powerband and frequent shifting is necessary to produce enough power for highway riding, but the rider becomes used to this. Chain attrition is swift and some form of extraneous lubrication is required, as the machine has no such provision. The chain was the only maintenance problem with the Mach III, aside from a speedometer light bulb, but it had other foibles. In fact, last year’s Kawasaki appears to have been a better machine for touring, as extensive use by some of our group would seem to indicate. The ’69s would get between 30 and 39 mpg at 80 mph, whereas the current model rarely gets over 25 and may drop to 18 in a headwind. With a 3.7-gal. capacity, the range is less than 100 miles. Acceleration was extremely rapid to a top speed of 110 mph while equipped with a Wixom Ranger. Braking and handling were both good, but this machine, like many other Kawasakis, had a very dangerous high speed instability when pushing a fairing.

MOTO GUZZI AMBASSADOR

The Moto-Guzzi 750 was purchased on May 16, 1970 and had covered 14,121 miles by October 1. During this time there was almost no maintenance on this machine except for oil changes. A speedometer bulb and a taillight bulb were replaced at just over 1 1,000 miles and the rear tire, a German Metzler, was entirely bald at 8600 miles with nary a wheelspin. It was replaced with a German Continental.

Comfort and handling were the Guzzi’s greatest attributes, though the BMW had softer rear springing. Seating was excellent and vibration minimal at highway speeds. At above 80 mph it vibrated more than the BMW, but it was not offensive. Scarcity of dealers and lack of spare parts seem to be the greatest problem faced by Guzzi owners, as indicated by our experience and interviews.

However, we ran into another problem that, though it did not occur on the test machine, thoroughly laid waste to two Guzzis and almost ruined a third. This problem concerns a check valve on the crankcase vent system located atop the engine between the carburetors. Should this valve stick the engine oil will be siphoned out of the crankcase until it is empty, with obviously serious consequences.

Frequency-of-occurrence data on this difficulty is not available, but if our limited amplitude of observation has disclosed three such incidents it may be fairly prevalent and therefore constitutes a very disparaging feature on an otherwise outstanding motorcycle. Handling and braking were extremely gratifying for a machine of this size and weight, as was the performance in other respects, though the BMW would accelerate faster.

(Continued on page 30)

Continued from page 28

Gas mileage was 41-43 mpg at 80 mph and top speed with a Wixom fairing was 1 00 mph.

It need not be said that, even after this costly and time consuming test, any one motorcycle proved itself decisively better than the others. All were outstanding in some respects while lacking in others, and we can only conclude that the most influential factors in motorcycle purchase inducement are undoubtedly as much emotional as they are empirical, and one could scarcely wish it otherwise.

Alan R. Johnson (no address given)

You and your friends are true enthusiasts, Alan! Thanks for sharing these thorough impressions with our readers. The one exception we have has to do with the BMW; our test machine (Dec. 1970) exhibited no wobbling tendencies in sustained cruising between 80 and 95 mph. It had no windshield. Some windshield designs may induce such a problem, as they set up front end oscillation. Even handlebars that are too wide for road work may cause the wind to batter the outspread arms and induce an oscillation, which makes the rider think he has a handling problem. Switching to narrower bars helps. —Ed.

NO RESPONSE

It is certainly gratifying to read that somebody is laying the blame for parts service where it belongs. (CYCLE WORLD, April 1971, Mr. Bergmen)

I am well aware of his complaint. I have been a dealer for a European-made motorcycle for several years, and am unable to get any response from the importer on parts manuals or information on the latest oil injection models.

1 have one customer that has personally written to the importer for a manual and parts, but it is quite evident that his letter has received the same treatment that was accorded mine. I have also been relieved of my dealership by this same importer because I (according to them) did not buy enough motorcycles from them. This same importer has refused to take back my stock of parts that I will no longer have use for, which is in direct contradiction to their written agreement.

I wish to thank Mr. Bergmen for going to bat for the dealer, as, in many instances, the fault does not lay with the dealer.

Herbert H. Collins Mustang Motors Rawlings, Md.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

SEPT 1971 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Technical, Etc.

Technical, Etc.Balancing the Mighty Multi

SEPT 1971 1971 By Gary Peters, Matt Coulson -

Features

FeaturesIt's A Steal

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joseph E. Bloggs -

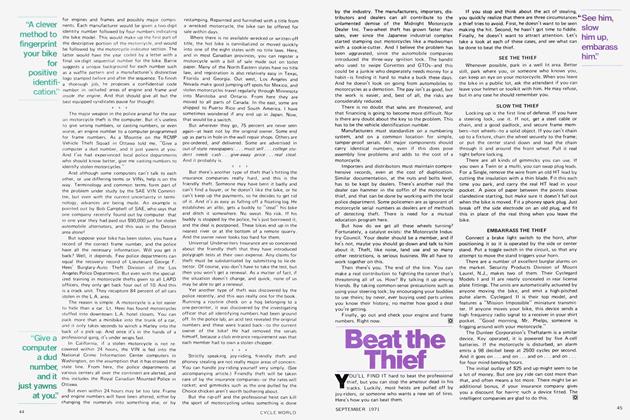

Beat the Thief

SEPT 1971 1971