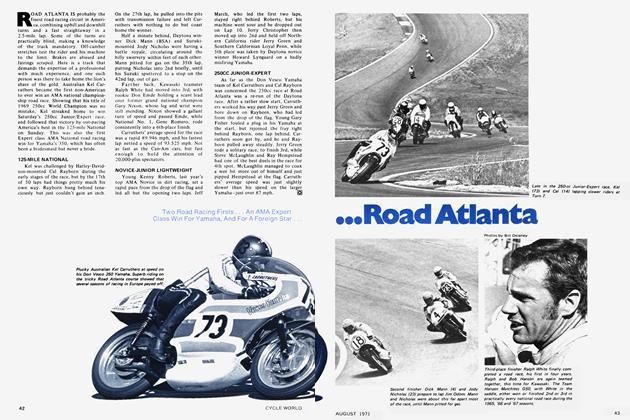

JOE SCALZO

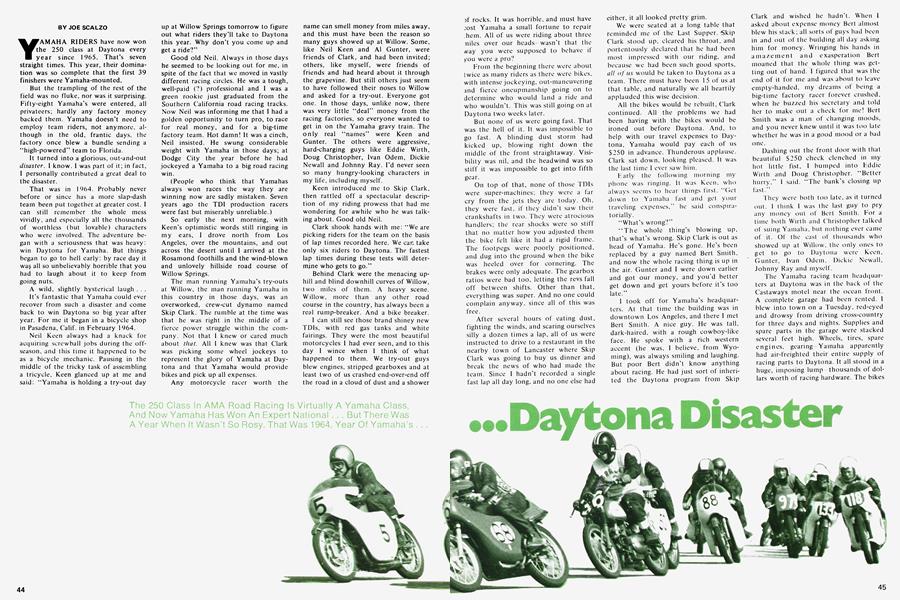

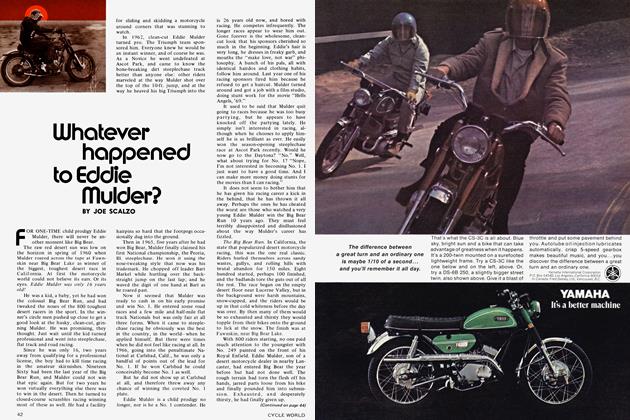

YAMAHA RIDERS have now won the 250 class at Daytona every year since 1965. That’s seven straight times. This year, their domination was so complete that the first 39 finishers were Yamaha-mounted.

But the trampling of the rest of the field was no fluke, nor was it surprising. Fifty-eight Yamaha’s were entered, all privateers; hardly any factory money backed them. Yamaha doesn’t need to employ team riders, not anymore, although in the old, frantic days, the factory once blew a bundle sending a “high-powered” team to Florida.

It turned into a glorious, out-and-out disaster. I know. I was part of it; in fact, I personally contributed a great deal to the disaster.

That was in 1964. Probably never before or since has a more slap-dash team been put together, at greater cost. 1 can still remember the whole mess vividly, and especially all the thousands of worthless (but lovable) characters who were involved. The adventure began with a seriousness that was heavy: win Daytona for Yamaha. But things began to go to hell early: by race day it wa$ all so unbelievably horrible that you had to laugh about it to keep from going nuts.

A wild, slightly hysterical laugh . . . It's fantastic that Yamaha could ever recover from such a disaster and come back to win Daytona so big year after year. For me it began in a bicycle shop in Pasadena, Calif, in February 1964.

Neil Keen always had a knack for acquiring screwball jobs during the offseason. and this time it happened to be as a bicycle mechanic. Pausing in the middle of the tricky task of assembling a tricycle, Keen glanced up at me and said: “Yamaha is holding a try-out day up at Willow Springs tomorrow to figure out what riders they’ll take to Daytona this year. Why don’t you come up and get a ride?”

Good old Neil. Always in those days he seemed to be looking out for me, in spite of the fact that we moved in vastly different racing circles. He was a tough, well-paid (?) professional and I was a green rookie just graduated from the Southern California road racing tracks. Now Neil was informing me that I had a golden opportunity to turn pro, to race for real money, and for a big-time factory team. Hot damn! It was a cinch, Neil insisted. He swung considerable weight with Yamaha in those days; at Dodge City the year before he had jockeyed a Yamaha to a big road racing win.

(People who think that Yamahas always won races the way they are winning now are sadly mistaken. Seven years ago the TDI production racers were fast but miserably unreliable.)

So early the next morning, with Keen's optimistic words still ringing in my ears, I drove north from Los Angeles, over the mountains, and out across the desert until 1 arrived at the Rosamond foothills and the wind-blown and unlovely hillside road course of Willow Springs.

The man running Yamaha’s try-outs at Willow, the man running Yamaha in this country in those days, was an overworked, crew-cut dynamo named Skip Clark. The rumble at the time was that he was right in the middle of a fierce power struggle within the company. Not that 1 knew or cared much about that. All I knew was that Clark was picking some wheel jockeys to represent the glory of Yamaha at Daytona and that Yamaha would provide bikes and pick up all expenses.

Any motorcycle racer worth the name can smell money from miles away, and this must have been the reason so many guys showed up at Willow. Some, like Neil Keen and AÍ Gunter, were friends of Clark, and had been invited; others, like myself, were friends of friends and had heard about it through the grapevine. But still others just seem to have followed their noses to Willow and asked for a try-out. Everyone got one. In those days, unlike now, there was very little “deal” money from the racing factories, so everyone wanted to get in on the Yamaha gravy train. The only real “names” were Keen and Gunter. The others were aggressive, hard-charging guys like Eddie Wirth, Doug Christopher, Ivan Odern, Dickie Newall and Johnny Ray. I’d never seen so many hungry-looking characters in my life, including myself.

Keen introduced me to Skip Clark, then rattled off a spectacular description of my riding prowess that had me wondering for awhile who he was talking about. Good old Neil.

Clark shook hands with me: “We are picking riders for the team on the basis of lap times recorded here. We can take only six riders to Daytona. The fastest lap times during these tests will determine who gets to go.”

Behind Clark were the menacing uphill and blind downhill curves of Willow, two miles of them. A heavy scene. Willow, more than any other road course in the country, has always been a real rump-breaker. And a bike breaker.

I can still see those brand shiney new TDIs, with red gas tanks and white fairings. They were the most beautiful motorcycles 1 had ever seen, and to this day I wince when I think of what happened to them. We try-out guys blew engines, stripped gearboxes and at least two of us crashed end-over-end off the road in a cloud of dust and a shower of rocks. It was horrible, and must have cost Yamaha a small fortune to repair them. All of us were riding about three miles over our heads wasn’t that the way you were supposed to behave it you were a pro?

The 250 Class In AMA Road Racing Is Virtually A Yamaha Class, And Now Yamaha Has Won An Expert National . . . But There Was A Year When It Wasn’t So Rosy. That Was 1964, Year Of Yamaha’s . . .

...Daytona Disaster

From the beginning there were about twice as many riders as there were bikes, with intense jockeying, out-maneuvering and fierce oneupmanship going on to determine who would land a ride and who wouldn’t. This was still going on at Daytona two weeks later.

But none of us were going fast. That was the hell of it. It was impossible to go fast. A blinding dust storm had kicked up, blowing right down the middle of the front straightaway. Visibility was nil, and the headwind was so stiff it was impossible to get into fifth gear.

On top of that, none of those TDIs were super-machines; they were a far cry from the jets they are today. Oh, they were fast, if they didn't saw their crankshafts in two. They were atrocious handlers; the rear shocks were so still that no matter how you adjusted them the bike felt like it had a rigid frame. The footpegs were poorly positioned, and dug into the ground when the bike was heeled over for cornering. The brakes were only adequate. I he gearbox ratios were bad too, letting the revs tall off between shifts. Other than that, everything was super. And no one could complain anyway, since all of this was free.

After several hours of eating dust, fighting the winds, and scaring ourselves silly a dozen times a lap, all of us were instructed to drive to a restaurant in the nearby town of Lancaster where Skip Clark was going to buy us dinner and break the news of who had made the team. Since 1 hadn’t recorded a single fast lap all day long, and no one else had either, it all looked pretty grim.

We were seated at a long table that reminded me of the Last Supper. Skip ('lark stood up, cleared his throat, and portentously declared that he had been most impressed with our riding, and because we had been such good sports. all of us would be taken to Daytona as a team. There must have been 15 of us at that table, and naturally we all heartily applauded this wise decision.

All the bikes would be rebuilt, ('lark continued. All the problems we had been having with the bikes would be ironed out before Daytona. And, to help with our travel expenses to Daytona, Yamaha would pay each of us S250 in advance. Thunderous applause, (’lark sat down, looking pleased. It was the last time 1 ever saw him.

Farly the following morning my phone was ringing. It was Keen, who always seems to hear things first. “(íet down to Yamaha fast and get your traveling expenses,” he said conspiratorially.

“What’s wrong?”

“The whole thing’s blowing up, that’s what’s wrong. Skip Clark is out as head of Yamaha. He’s gone. He’s been replaced by a guy named Bert Smith, and now the whole racing thing is up in the air. Gunter and 1 were down earlier and got our money, and you'd better get down and get yours before it’s too late.”

1 took off for Yamaha’s headquarters. At that time the building was in downtown Los Angeles, and there 1 met Bert Smith. A nice guy. He was tall, dark-haired, with a rough cowboy-like face. He spoke with a rich western accent (he was, I believe, from Wyoming), was always smiling and laughing. But poor Bert didn’t know anything about racing. He had just sort of inherited the Daytona program from Skip ('lark and wished he hadn’t. When l asked about expense money Bert almost blew his stack; all sorts of guys had been in and out of the building all day asking him for money. Wringing his hands in amazement and exasperation Bert moaned that the whole thing was getting out of hand. I figured that was the end of it for me and was about to leave empty-handed, my dreams of being a big-time factory racer forever crushed, when he buzzed his secretary and told her to make out a check for me! Bert Smith was a man of changing moods, and you never knew until it was too late whether he was in a good mood or a bad one.

Dashing out the front door with that beautiful $250 check clenched in my hot little fist, 1 bumped into Fddie Wirth and Doug Christopher. "Better hurry,” 1 said. “The bank's closing up fast.”

They were both too late, as it turned out. I think 1 was the last guy to pry any money out of Bert Smith. For a time both Wirth and Christopher talked of suing Yamaha, but nothing ever came of it. Of the cast of thousands who showed up at Willow, the only ones to get to go to Daytona were Keen, Gunter, Ivan Odern, Dickie Newall, Johnny Ray and myself.

The Yamaha racing team headquarters at Daytona was in the back of the Castaways motel near the ocean iront. A complete garage had been rented. 1 blew into town on a Tuesday, red-eyed and drowsy from driving cross-country for three days and nights. Supplies and spare parts in the garage were stacked several feet high. Wheels, tires, spare engines, gearing Yamaha apparently had air-freighted their entire supply oi racing parts to Daytona. It all stood in a huge, imposing lump thousands of dollars worth of racing hardware. The bikes were still crated up and no one seemed in a hurry to unpack them. I sat down on a crate in the garage to see what was going to happen next.

Some of my fellow “factory” riders joined me during the day, including Newall and Odern. Right away we started quarreling as to who was going to ride what bike. We were all grumbling that we should be out at the track practicing but no one was listening or uncrating the bikes. Keen and Gunter, the wise veterans, had already taken one look at the disorganized scene in the garage, grabbed a couple of bikes and left for their own private headquarters where they could prepare the bikes themselves and not be disturbed.

At Willow Springs only California riders had attended the try-outs. But now all sorts of East Coast dudes were stopping by the garage, claiming that so-and-so Yamaha dealer had promised them a ride and where were their bikes? It was frantic.

The bikes were being grabbed off so fast that finally I uncrated one myself and sat on it.

A little later a tall, bow-legged guy with a Texas accent walked into the garage and drawled softly, “Is there a Yamaha for me here?” I told him I didn’t think so, and he left emptyhanded. Later someone told me it had been Buddy Elmore, one of the fastest road racers in the country. Gary Nixon also stopped by, loudly announcing that someone at Yamaha had promised him a bike for the race and where was it. Nixon, too, was sent away emptyhanded.

Of course if Bert Smith and the rest of the Yamaha people had been thinking a little more clearly they would have welcomed Elmore and Nixon with open arms, fired the rest of us, tried to get the expense money back, and then turned over all the equipment to Nixon and Elmore and concentrated on them. That might have prevented the disaster that followed. But no one was thinking too clearly, apparently, not even Bert Smith, who had already gone a couple of days without sleep trying to get matters sorted out.

Once uncrated, none of the bikes would run right. The race was only a couple of days away. The garage was overflowing with onlookers, with riders who had been promised rides and were there to claim their bikes, and with big shots from the Yamaha factory who had come to Daytona to watch their machines win.

The lone, smiling, cheerful face in the midst of all this belonged to Larry Beall. Beall was a stubby, husky Texan with a lusty accent and the build of a weight lifter. He was a nice guy, and he seemed harmless until you looked at his eyes: Beall had very wild eyes. Anyone I have ever known with eyes like that has turned out to be a hell raiser down deep, and Beall was no exception. But for the first couple of days he was on good behavior. He worked for Yamaha, and he used to race professionally. Naturally, he was hopeful of riding one of the Yamahas in the race. But Bert Smith was very much against it.

Bert Smith and Larry Beall plainly hated each other. Every time they were together you could feel the tension building up. Beall told me that the feud had started the year before when he and Bert had flown to Japan together on business for Yamaha. One of the plane’s engines had conked out over the Pacific and the pilot had had to crash land on Wake Island. He and Bert Smith had been playing blackjack together on the plane and during those last frantic seconds before the crash landing, Beall had played wildly and had cleaned poor Bert out of $600. That finished their friendship. I never knew if the story was completely true or not because everything about Larry Beall was a little unbelievable.

Gary Nixon, who was plenty wild himself in those days, was a friend of Beall’s. He was always stopping by the garage at night.

“Beall here?” he would ask.

All of us at the garage were under strict orders from Bert Smith to say no. Apparently when Nixon and Beall got together it became a game to see which one could outdo the other.

But one night they went out together on the town. They staggered back to the garage around two in the morning with the front of Beall’s truck bashed in where he had tagged a palm tree. The police arrived later and took Nixon away for rowdiness, but not Beall.

The next day Beall seemed upset by the whole thing. Why, he and Gary had done nothing wrong, he said. The police had no business locking up Gary for the night.

By then I’d been in the garage waiting for my bike for three days. That afternoon the mechanics had it ready. I trucked it out to the track, got in one practice lap during which I managed to run off the road at high speed but stay on two wheels, and the crankshaft sawed. Back 1 went to the garage.

Anything more complicated than a pair of pliers is too technical for me, so naturally 1 was going to have to get someone to pitch in and help me fix the broken engine. Beall and another Texan named Allan Jackson volunteered.

Jackson was a heck of a tuner. Soon he had the engine out of the frame and on the oil-soaked garage floor. That night the garage, as usual, was overflowing with people and other bikes being repaired. A nylon rope was stretched taut across the open garage door to hold the onlookers back. We felt like animals in a zoo.

Beall said he was certain that my Yamaha would run faster if we shortened up the skirts of the pistons. Well, why not? Beall held one of the pistons on the workbench and I attacked it with a blunt hack saw blade. Beall suddenly let out a yelp and jerked his hand away: “Godammit, you like to cut my finger off!” Apologizing profusely, I went on sawing. Poor Beall’s hand was bandaged up for the rest of his stay in Daytona.

We worked all night changing the crank, shortening the pistons, bolting the bike back together. But the next day, Friday, the last day of practice, the bike blew up again. So much for short pistons.

The Yamaha garage that night was submerged in gloom. The race was less than 24 hours away. Not one of the team bikes was running well; no one had had any practice. It was said that Bert Smith had gone without sleep for five days running, and relations between him and Beall were so brittle it was getting scary. The only Yamahas running well were those of Keen and Gunter, and they were far on the other side of town.

The two or three mechanics Yámaha had brought along were virtually out on their feet; they had had practically no sleep all week. But they gathered themselves up for one last stupendous effort. Somehow they would get all the bikes prepared for the race the next day.

Bert Smith, drawn and exhausted, gathered all us riders together. We were to report at the garage at seven in the morning and proceed to the track, Smith said. He wished us well.

Poor Beall, I was thinking, he still doesn’t have a bike. This was when Allan Jackson, Beall’s friend, took me aside.

“Have you ever seen Larry Beall race?” he asked me.

I confessed 1 had not.

“Well, let me tell you, that man is something. A crazy man. He’ll do insane things to win. Man he goes fast. He should be on a Yamaha tomorrow.”

Jackson went on in this vein for several minutes getting the point across that Larry Beall on a race track was like a fast-moving torpedo and could inflict just as much damage. Finally he got down to brass tacks: “Why don’t you let Larry ride your bike tomorrow?”

I recoiled in horror. “Listen,” I stammered, “I can’t do it. I’ve been in this garage for days, gone without sleep. Now I’ve come this far I have to at least start the race.” Jackson walked away looking disappointed.

I didn’t feel like getting up the next morning and going to the garage. 1 knew that the bikes still would be scattered in a million pieces; there was no way the mechanics could possibly have finished them on time.

But they had finished them, lhev had them shiny, assembled and ready to go. What’s more, they really ran last. Mine was like a jet. The engine simply ate up the blacktop on the backstraight.

1 felt happy for the first time since I'd arrived at Daytona.

But as 1 buzzed by the pits on the second lap of practice the engine made the now familiar “whee” sound, the revs went sky high, and 1 knew 1 had sawed another crank. The race was maybe two hours away.

Then 1 saw Larry Beall. He had talked someone into loaning him a TDI for the race. Now he was pushing the broken bike (it had also sawed a crank during practice) at top speed toward his truck in the parking lot. Allan Jackson was running after him.

“Where are you going?” 1 called at Beall.

“Going back to the garage,” he shouted back over his shoulder, still running with the bike. “Going to load the bike into the truck, take it to the garage and change engines.”

I followed, pushing my bike into the back of Beall’s truck. By God, I'd change my engine too!

Beall drove through traffic like a fiend. 1 sat up in the cab with him. Allan Jackson was in the back, holding onto the Yamahas. There hadn't been time to rope them in. We hit the right-hand corner just before the Halitix bridge in a wild tire-burning broadslide, crossed the double white line, the truck went up on two wheels, nearly hit a guardrail, then kept going. Somehow neither Jackson nor the bikes were thrown out of the truck.

The scene at the garage is a blur to me now; we dove into that pile ot spares like gophers, emerged with two tresh engines, and somehow, in less than 45 minutes of frantic running around, slipping and falling into the oil, and smashing our knuckles, got the engines in both bikes changed.

Beall drove even faster back to the track than he did getting to the garage because the race was going to start in less than 10 minutes. In the bed of the truck Jackson was busy with wrenches tightening’the last bolts on the bikes.

When we arrived we could hear the scream of the engines. The race was lining up. As we unloaded the bikes from the truck someone said that Gunter, Keen, Tommy Clark, Nixon (who must have found a Yamaha somewhere) and Bill Erickson all had qualified on the front row. An entire Yamaha front row. Beall and 1. by comparison, would be starting side-by-side in the last row, with only about 1 10 bikes between us and the front row.

As we pushed our bikes toward the starting line as fast as we could go, who should we see but Bert Smith. Beall and 1 were both greasy and oil-stained from working on the bikes. Bert gave both ot us dirty looks, and Beall started to growl something under his breath. It looked for a moment that Smith and Beall finally were going to come to blows one minute before the race st a rted.

Then Bert said: “Good luck, you t wo.”

Beall and 1 found our starting positions on the back row. The smoke and engine noise was heavy in the air. Just before the start Beall leaned over and yelled: “Listen, don’t stay back here before the start. Creep forward. They can't see you through the smoke. It you have to start back here, you'll never catch up.” So said, he began creeping. Those wild eyes ot his, 1 had noticed, were flashing.

1 was creeping too. By the time the starter threw the flag, I was nearly in the middle of the pack. For one glorious moment it seemed like the nightmare was going to have a beautiful ending. The bike shot forward with the front wheel off the ground, blazing through traffic. It was a jet.

1 hit the banked first turn and 1 was close enough to the front 1 could see the leaders up ahead. Keep going baby. 1 said as 1 caught fifth gear. This was when the crankshaft sawed again. All power disappeared. There was a thundering mob of 50 or 60 riders behind me. and all 1 could think of was getting clobbered and run down by all ol them.

1 held up my arm. looked over my shoulder and all 1 could see was traffic. This is going to hurt, 1 thought. Somehow they all missed me.

I steered the broken bike down otf the banking into the infield. 1 didn’t feel distressed, just happy that the whole mess was over. The race was still roaring around the track. 1 had no idea who was leading and only hoped it was a Yamaha.

Slowly 1 started pushing the bike back to the pits. As 1 got closer, a couple of the Yamaha mechanics spotted me coming and started running toward me. 1 thought they were going to help me push the bike. Instead they immediately started yanking the gas tank off! “What the hell's going on?” 1 demanded. No answer. The last 1 saw ot the two of them, they were running toward the pits with my gas tank and 1 was standing there with a cannibalized motorcycle. (Gary Nixon apparently liad split open the gas tank of his bike the first lap and hail called at the pits for a new one. So they had taken mine!)

As for the race, Dick Hammer on a Harley Sprint and Norris Rancour! on a Barilla simply blew all the Yamahas olt the track and finished 1-2. Gunter and Keen finished 3rd and 4th. both badly beaten. Beall, after devouring three quarters of the field, was steadily gaining on the leaders, riding fantastically, when his crank sawed. Other equally terrible things cut down all the other team Yamahas.

The Yamaha garage did not seem a good place to return to that night, considering the circumstances. So 1 curled up under a friend's truck and slept on the ground, somehow losing all that remained of my expense money. I nearly starved on the trip home.

The next year. 1465, Yamaha did not ask me to rejoin their team, the bums. But they hired Dick Mann and Mann won the race for them easily. That was the start of Yamaha's Daytona reign and it is still going on. Somehow they curbed the TDI’s appetite tor cranks, and also made it handle. Most ot the people 1 knew in '64 are long gone. Bert Smith left Yamaha not too long after the debacle, and no one seems to know where he is now. Neil Keen now lives in St. Louis, and no longer works in a bicycle store. And Larry Beall Larry Beall is presently selling Hondas in Texas.

I saw Beall in Daytona this year. After seven years his eyes don’t seem quite as wild. He told me he has calmed down a lot but I didn't believe him. He also showed me his left hand. It is incredible the scar a hack saw blade can leave, even after seven years.