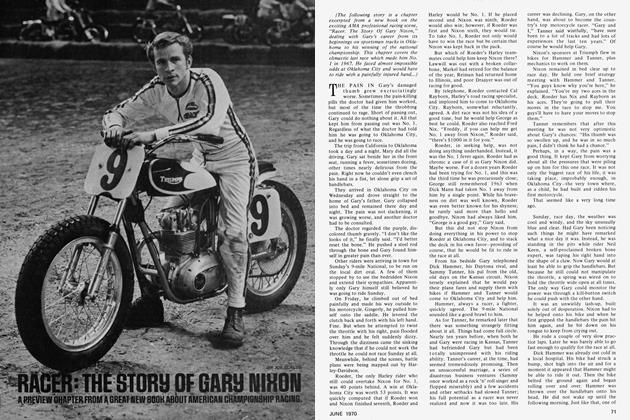

TOURING THE NETHERLANDS

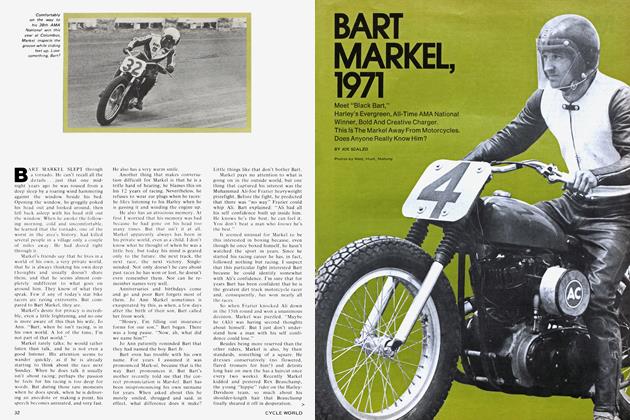

JOE SCALZO

THE WORD IS OUT about the Netherlands. Most everyone, for example, knows Holland has windmills, wooden shoes, tulips, an out-of-control population which registers 920 people to the square mile, and inflation. And if that unknown kid hadn’t jammed his thumb into the dike, there’d be no Netherlands at all.

But the Big Secret is that Holland is the land of the motorcycle, and the big secret is a controversial one. As a matter of fact, it’s so controversial that 70,000 Dutch motorcycle riders don’t believe it. They migrate from their country at every opportunity, preferring sunny sojourns in Italy or Spain. They have their reasons.

I was in Holland six weeks, and after being initially charmed by the fantastic green countrysides and the narrow, winding roads — roads somebody absolutely designed for motorcycles — I came home sadder, but wiser. For there are also cars on those great roads, cars which number over one million. And, as I’ll explain, cars and car drivers are the one crying fault with motorcycle touring in Holland.

Picture a country 1/20 the size of California, a country so small you can see it in a day, but one that presents so many faces you really couldn’t see them all in a year, and that’s Holland. But picture a country where everything is changing, where the old is being pushed aside for the new, often with clashing results, and that, too, is Holland. Holland is most of all old, and the 12th century (and earlier) structures that dot the polder scape are as common as the endless fields of ancient and obsolete windmills. Yet, standing amidst the windmills are towering 20th century by-products like radio and television towers, including the awesome Lopik in the Hilversum area. And if you really want jarring contrast, compare the Rotterdam harbor, the world’s first, and, in terms of annual tonnage, largest, with the tiny and timeless Yssel Lake fishing villages of Vollendam and Marken.

But from a motorcyclist’s point of view, the key change is in transportation. For years Dutchmen rode bicycles, but just as windmills are apparently on the way to extinction, so too are the bicycle hordes. Replacing them are sub-50cc mopeds, or brommers in Netherland lingo. Eighteen is the requirement for an auto or motorcycle license, but not for a brommer, which anyone 16 years of age may legally ride. Thus, mopeds such as Magneets, Berinis, Spartas, Mobylettes, Solexes, Flandrias, and even Hondas outfitted with pedals, streak through the streets of Holland in numbers the police peg at one million.

Great, you say, a shot-in-the-arm for the Dutch motorcycle industry. In this case, it’s a shot-in-the-arm in reverse. For when people graduate from brommers, it is usually to cars, such as the Dutch-built Daf. The one million cars will double by 1970, and if there’s anything Holland doesn’t need, it’s more cars.

One Dutch dealer said high motorcycle prices were the reason for the surge in car sales and the resultant drop in motorcycles. “There’s hardly any price difference between a motorcycle and a car in Holland, so a person usually chooses a car.” Others, however, like John Meirdres, a motorcycle shop owner in Breda, levels the blame on the brommers. Meirdres thinks moped misadventures tend to sour a person on motorcycles. “The average rider knows nothing about mechanics,” Meirdres claims. “He sees the cheapest brommer costs the same as a good bicycle. So he buys it, then expects it to run 10 years, just like a bicycle. Of course, it doesn’t, so he either painfully goes back to a bicycle or buys a car.”

If he lives long enough, that is. For far more stunning than brommer economics is the way their fearless owners cavort through city streets. In a country where even school children must possess bicycle licenses, the absurdly reckless attitude is like steel skid shoes at a Motor Maid parade. Brommer riders — both male and female — are sensationally bad. The cheery nonchalance they exude while ripping through traffic would put American street racers to shame. Their accident rate is the highest in Holland, and with traffic agencies concentrating solely on the exploding car population, there is no relief in sight.

But the cars, too, deserve attention. It is going some when Dutch automobile drivers are worse than the Belgians, who by law don’t even have to have licenses, but it’s true. In plain language, Dutch drivers are the worst on the face of the earth. They show no concern for their fellow motorists, which puts cyclists on a lower, and even deadlier, plateau.

A continual war is accordingly waged between motorcycles, brommers, and cars, particularly with Holland’s new breed of big-car taxi drivers. The hard-charging cabbies find the buzzing two-wheelers “Verschrikkelyk!” (terrible) and react accordingly. Motorcycles and notably, mopeds, always come out second best, and the only group worse off are the hapless pedestrians, who apparently have no rights at all.

Grudgingly, I developed a certain empathy toward brommers. Regularly run down by cars, the drivers of whom seem to consider it a favorite pastime, brommers nevertheless fight back by sheer number. And, harsh riding manners aside, there are some born road racers steering these under-50cc bikes. Avenues in Holland are slick whether wet or dry — especially when they are made of the king-sized cobblestones known as kinderkopjes. I won’t forget the girl I saw “ear-holing” a brommer, correcting gently as the back wheel slipped.

Motorcycle sport is sweepingly popular in Holland and is presided over by the 25,000-member KNMV (Koninklyke Nederlandse Motoryders Vereniging), a 50year-old organization domiciled in The Hague. KNMV is the FIM Holland arm, and though splinter factions occasionally spring up to combat its power, KNMV is the omnipotent force in the Netherlands. Sanctioning amateur road racing, motocross, and grass track meets, KNMV boasts 75 chapters, an excellent insurance policy, and a readable club organ, Motor.

American groups from the AMA down would do well to copy the KNMV road race licensing system, which is dependent on a rider’s ability rather than his physical condition. Though a rider must pass a rigid physical and be at least 18 and in possession of a driver’s license, the real test comes each January at the Zandvoort circuit. Old hands and newcomers are all treated as equals. Machines are broken down into classes and each rider is dispatched for a three-lap burst, his fastest lap standing as his official time. That lap must be within 15 percent of the fastest lap in the class. If it isn’t, no license is issued. (There are, however, special meets later in the season where a rookie may participate to gain experience.)

The system is harsh, as the ratio of 200 license holders to 600 non-license holders shows. But the Dutch justifiably believe road racing to be dangerous and only those who can qualify are allowed. The relatively fatality-free KNMV record underscores this.

Once a national license is in his hand, a rider has a chance of grabbing off a real bauble. Each year a five-man KNMV commission mercilessly screens all license holders, and at season’s end, recommends a quartet they feel should be granted international licenses. This entitles holders to compete in major events outside Holland, with KNMV paying traveling expenses. This chance to become a card-carrying pro is something all serious riders shoot for. But it isn’t easy, and there have been years when no international licenses were awarded. Even today there are but 16 of them, the best being Cees Van Dongen, a 10-year vet who campaigns a stable of Hondas.

A more typical rider is Piet van de Goorberg, 22, the national 350cc titlist. Van de Goorberg is a carpenter, in business with his two brothers, both of whom also race. Riding a near-stock 305cc Honda, van de Goorberg would like to become one of the “grote mannen' — his term for the Hailwoods and Reads — but he also has a family and racing is of necessity a hobby only. Eighty percent of the Dutch riders are in similar positions.

Van de Goorberg’s cut-down street machine is representative of Dutch racing equipment. Though more and more pukka racers are arriving, most are home-grown, giving an atmosphere of close, if not necessarily super-fast, racing. One inventive competitor, Martin Hijwaart built a 50cc Suzuki-based “Jomathi,” which is a match for the majority of the 125cc gear.

Six tracks sprinkled across Holland make up the circuit, all of them similar in that they are ultra short and with few straights. A favorite is the North Sea venue of Rockange, which careens through city streets, a la the Isle of Man. For safety reasons, however, Rockange racing is limited to 50 and 125cc. Other tracks, excluding Assen (site of the Dutch TT, and open only to international licenses) are Tubbergen, Etten, Zandvoort, Uden and Oldebroek. A rider may expect 10 races in a season, although KNMV is moving to bulk up the schedule.

All races draw enormous and well-behaved crowds (there are no 10 percenters in Holland, only long-haired Provos who are at best a weak imitation). In fact, sometimes the crowds are large enough to question the claim that soccer is indeed the most popular sport on the Continent.

Spiraling off the opposite way are the violent motocrosses.

It isn't so much the riders, who are good and game and the best in the world at what they do, it's the behavior of the absolutely mad spectators. It is the same all over Europe, and not just in the Netherlands. But Wolfslaar, just outside Giniken, was the first motocross I saw and a veritable lid-lifter for what followed.

The Wolfslaar course was a one-kilometer, 32-turn terror running across muddy, watery pastureland. After one lap everyone was caked with an inch of the soggy Weiland, but the majority of the entrants were irate only about the tame quality of track. “This is a safe track,” lamented one rider. “Too safe. I prefer riding through the forest.”

Meanwhile, the 5,000 spectators had stationed themselves five-deep at all corners. A thin strand of cable was all that kept them from flooding onto the course itself. With motorcycles bouncing past at distances ranging from one foot to one inch, you had to be a real enthusiast to be standing in the front row. Yet these people who did get showered in dirt or occasionally had a foot run over were ecstatic. Shortly afterwards, a big Triumph plowed through a portion of the human crashwall and the only damages were a bent set of handlebars.

But it wasn’t until I crossed over into Belgium that I got a really strong dose of the motocross madness. Belgium is the capital of the sport. This is a source of pain to the Dutch, who claim they invented it and now must darkly watch its overwhelming popularity in their neighbor country. The Belgians love their motocrosses. They also love Joel Robert, as I emphatically found out.

The track was at Balem, which is not on the map, but is located in the Hieheuvel area and ringed by great, green trees. The trees are for people to sit in because there is no room on the ground.

The traffic jam started five miles out of town and continued at a crawling pace, with white-gloved constables attempting to direct the sea of cars and motorcycles. At Wolfslaar there were 5,000 rednecks, but at Balem there were 30,000 — all of them emptying into the deep valley where the track was. Thirty thousand people, paying approximately three U.S. dollars a head, balanced against the somewhat sketchy appearance money system under which the leading riders operate. 1 wondered what Neil Keen and the MRI would say to that.

Then the races started, and the howl of the 360cc CZs swelled the size of the valley. Now, you’ve no doubt read the Latins are hot-blooded; I say it's the Belgians. On this incredibly fast, rutted and dangerous course, where even the best riders always looked wobbly, the spectator mobs pushed ever closer. They encouraged riders every way, from waving them on to slapping them on the backside. It was, amazingly, just like the old Mexican road race where peons would touch the Lincolns and Lancias as they scalded past.

The riders, for their part, took the wildness calmly — maybe because they were used to it. I never got used to it. At one point, a vendor was walking the length of the track, selling autographed shots of Joel Robert and Roger Decoster. The Robert photos were ‘a nickel cheaper. An enraged and slightly stoned Robert fan leaped onto the track, hailed the vendor, and discussion went like this; “You’re selling Joel Robert a nickel less.”

“So?”

( louder ) “Y ou’re-selling-J oel-Robert-a-

nickel-less!”

“So?”

(very loud) “You’re selling Joel Robert a nickel less!”

“So what?”

His patience shattered, the angered fan swiftly had the vendor by the throat, only to be immediately joined by more people who physically protested his action.

It should have been just another beef. But it was all taking place on the race track, and, hysterically, while the race was going on! With the fastest of the bikes running flat-out in third through the sector, the biggest problem was not staying on the road, but dodging the struggling participants.

So that’s motocrossing. Missing seeing at least one meet in Belgium is comparable to not going to Disneyland in Southern California, but there are other things to do, especially if touring is your game.

Everything is in Holland: scenery, variety, good, friendly people, prices that are right (only Spain and Greece are cheaper) and stupendous roads that fairly boil your blood. Actually, all the major woes of traveling in a foreign country — not speaking the language, not understanding the money, and getting sabotaged by the food — are miniscule in Holland. Practically everywhere you go, English is spoken, including restaurants and cafes, where half the menu is usually in English. Dollars are almost always accepted in restaurants (and gas stations), but there are enough change depots and tourist aid stations to make this unnecessary. The food may first seem strange, but the Dutch are singularly addicted to french fries, and who isn’t? I also found coffee all over Holland to be hand-ground and so good as to be totally unlike the American version. There are likewise plentiful camping grounds and hotel accommodations are inexpensive.

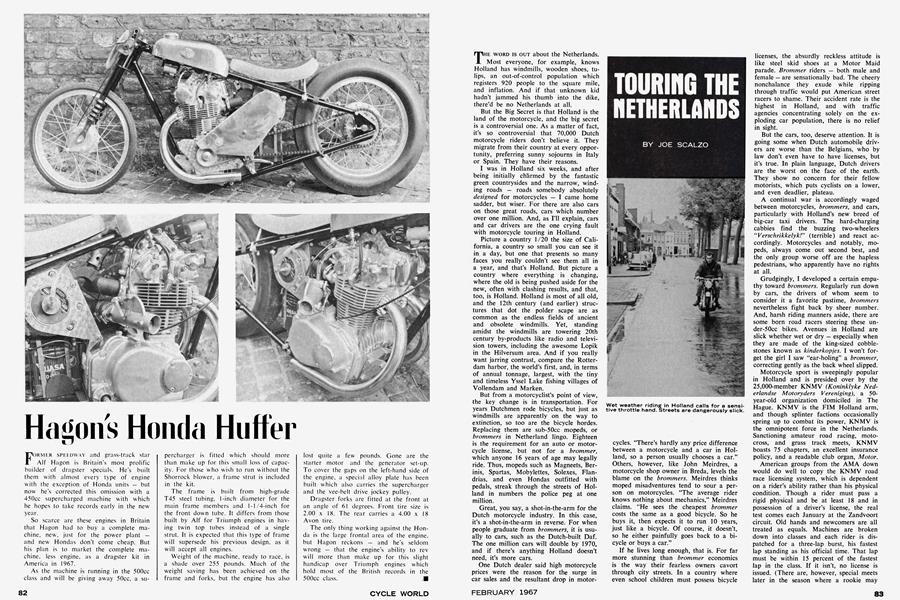

With a build-up like this, what prevents Dutch motorcycle touring from being all it should be? The car menace is the big part of it. The roads are fun and fast when you have them to yourself, but as soon as a car shows on the horizon — be prepared. Staggeringly, truck drivers operate at a level of recklessness that even exceeds car pilots. In any case, the combination of car and truck traffic is enough to make you park in frustration. On the quiet, so-called “picture roads,” the situation is acute, yet not so bad as the big snelwegs, the Dutch equivalent of turnpikes. With no speed limits posted, cars boom past at 80 to 90 mph, and always missing you by what seems inches. Should you try to imitate their speed, be reminded that while there are no speed limits per se, the major thoroughfares are still patrolled by special Zandvoort-trained police who commute in 115-mph blue-lighted Porsche Supers. An American driving license is acceptable, although an international driving license can be picked up for about $3.

As if to compound the automobile problem, Dutch authorities take a curious view, indeed, toward road signs. Signs are in severe shortage, and you particularly miss them when you get into a blind turn too hot, or as you blast across a railway crossing you didn’t know was there. As long, black trains shuttle across Holland at all hours, you invariably make their acquaintance.

The weather is also a constant joker. Rain is practically a daily occurrence and no Dutchman goes anywhere without packing a rain coat. You shouldn’t, either. When the water does come down, the pavement gets slick so fast, you can finish up in a ditch just by blinking. Avoid riding in the rain, especially at night. Truly, the only thing worse than riding in the rain at night is getting caught in the infamous early-morning ground mist. Besides being bone-numbing and impossible to see through, it burns off with infuriating slowness.

If you understand all this, you’re ready to tour the Netherlands.

It can be done casually or quickly, and the following circle-Holland tour I’ll describe can be accomplished in a day or a week, depending on your pace.

The Hague is a good place to begin. Holland's third largest, and possibly most affluent city, sits solidly against the North Sea and contains no fewer than 16 museums — one of them, Mauritshuis, holds the majority of Rembrandt's work. There is also Binnenhof, where Dutch parliament convenes, the International Court of Justice, and the tourist refuge, Madurodam. This last, an actual Dutch city reproduced at I/25th scale and set in an area the size of a football field, is well worth seeing if you have the time. It’s a two-mile walk all the way through.

A final stop before departing The Hague is the beach and pier at Scheveningen. Historically interesting because the Dutch underground used it as a code word during World War II to guard against infiltration (only a true Dutchman can pronounce it correctly), it is now Holland's over-crowded answer to the Riviera. A very classy strip of white beach, wellstocked with mini-bikinis, it boasts the most savory salt air in the Netherlands.

Leaving The Hague you’ll go through the village of Delft, where, since 1653, craftsmen have been turning out the gleaming Delft's Blauw china, and just out of Delft the road shoots into Rotterdam, a good city to stay away from during the rush hour.

In-town riding calls for the greatest caution. The motorcyclist must remember the ironclad rule which gives anyone and anything coming from the right the right-of-way. This simply means if you're doing 35 mph down a main street and a car pulls from a driveway, lock everything up and stop — if you can.

Rotterdam sparkles with life. SPIDO boat shows show off the huge harbor, but if you don't like boats, there’s the view from the 392-foot Euromast tower. An elevator runs to the top, delivering a commanding look at both the harbor and all of downtown. A swank restaurant in the tower's lid serves American food and afterwards you might try a trip through the Maas tunnel which travels directly under the river of the same name. Off in the downtown area, and well worth more than a glance, is Ossip Zadkine's "Monument to a Devastated City,” a brilliant remembrance of the sacking of Rotterdam by Nazi planes in 1940.

Twenty minutes west of Rotterdam is the ambitious Deltaworks. The everlasting battle with water is a cornerstone of Netherland history and the Dutch build dikes like Rembrandt sketched a canvas. A fact not much noted (except by the Dutch themselves) is that almost all of Holland is actually below sea level, and this, the Deltaworks, is the latest attempt to claim land from the North Sea. Five new dikes are being constructed, and with 90 percent of the rivers of Holland emptying into the basin where the work is being carried out, the project is clearly a major one. Of the several daily boat tours that explore the works, the trip from Hellevosluis is perhaps the best. Another resident of the delta area is the mammoth Oosterschelde Bridge, a three-mile, $20 million structure spanning the rough Oosterschelde River.

Motoring south from Rotterdam, some of the rural farm land still bears the flood scars of the great dike-breaking disaster of 1953, which killed 2,000. Also in the vicinity is Kinderdyk, where windmills are big and a cluster of 17 line up next to an old dike.

Located 110 kilometers south of Kinderdyk is Arnhem, a green, woodland-surrounded metropolis where the Rhine, Wall, and Ijeel rivers all converge. The woods of Arnhem are scenic and still, but they were the theater for one of the most costly battles of World War II in 1944. A huge military cemetery for the Polish and British veterans now rests on the city’s outskirts.

Turning north and crossing through the province of Gelderland, the road becomes narrower and less clogged with trucks and autos. The further north you ride, the earthier the atmosphere becomes. This is the land of the old Zuider Zee (now called the Yssel Lake) and maybe where the real Holland begins. Of all the 12 provinces, I liked Friesland best. It’s rainy, and old, and thinly populated, and the natives speak in a dialect no other Hollander understands. But even though Friesland does not capture the snap and bustle of Rotterdam or Amsterdam, it has 11 cities, 350 villages, and 150 windmills. Best of all, the roads are usually blissfully free of the four-wheeled man eaters.

Much time can be spent studying the various attractions, such as the planetarium in the town of Frankeer. A craftsman named Eise Eisinga began building it in the 18th century and finished only after seven years of intricate work. However, easily the best known products of the province are those which bear its name: the hand-crafted, hand-painted Fries clocks and the brutish Friesland horses.

You leave Friesland by riding across the impressive Afslultdyk, the great 20-mile dike which finally and forever sealed off the old Zuider Zee from the North Atlantic ocean.

On the western side of the Afshdtdyk in the province of North Holland, the land retains its pleasant, factory-less atmosphere. Like Friesland, there are a number of side trips to be taken. Vollendam and Marken, the twin fishing villages where time stopped long ago, are among the last places in the Netherlands where citizens still wear the old costumes, the men in black bell-bottoms, tight jackets, and visored caps, the women in floorlength apron dresses and bonnets. And both banging about in wooden shoes. Although both towns are tourist centers, the inhabitants remain resentful to all outsiders. The sealing off of the Afshdtdyk ruined fishing, and not one resident of Vollendam or Marken has forgotten. This is particularly so on Marken, which used to be a lonely island with a slow ferry service, but now has a giant causeway connecting it to the mainland.

Swinging north from Marken into Haarlem, Holland's most beautiful and classic city (and home of the Zandvoort track) brings you within 30 kilometers of The Hague, meaning you've spun almost a complete circle. The 30 kilometers between the two cities is a fertile belt which can be a riot of mixed colors from April to mid-May, that portion of the year known as Tulip Time.

Like any brief tour, the things you miss may stand as glaring omissions — Amsterdam, the city of diamonds, for one example, the lush countrysides of central Holland for another, and certainly the chain of Wadden Islands near the Afshdtdyk.

I liked Holland, car problems notwithstanding. Of course, I never developed the baffling lightheartedness of the brommers. That segment of riders, thumbing their noses at all and sundry with their wacky riding, just might have the best attitude of all.