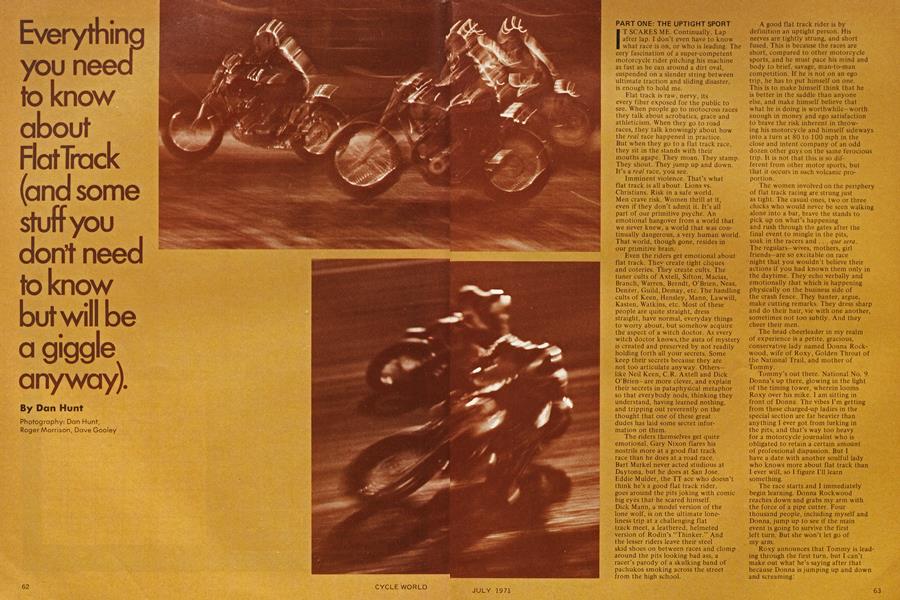

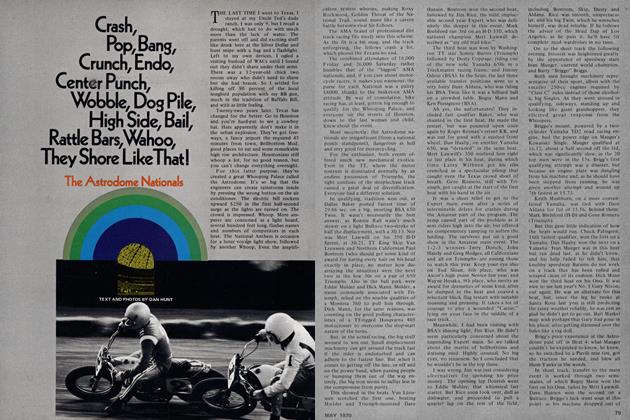

Everything You Need To Know About Flat Track (and Some Stuff You Don't Need To Know But Will Be A Giggle Anyway).

July 1 1971 Dan HuntEverything You Need To Know About Flat Track (and Some Stuff You Don't Need To Know But Will Be A Giggle Anyway). Dan Hunt July 1 1971

Everything you need to know about Flat Track (and some stuff you don't need to know but will be a giggle anyway).

Dan Hunt

PART ONE: THE UPTIGHT SPORT

IT SCARES ME. Continually. Lap after lap. I don't even have to know race is on, or who is leading. The eery fascination of a super-competent motorcycle rider pitching his machine as fast as he can around a dirt oval, suspended on a slender string between ultimate traction and sliding disaster, is enough to hold me.

Flat track is raw, nervy, its every fiber exposed for the public to see. When people go to motocross races they talk about acrobatics, grace and athleticism. When they go to road races, they talk knowingly about how the real race happened in practice.

But when they go to a flat track race, they sit in the stands with their mouths agape. They moan. They stamp. They shout. They jump up and down. It’s a real race, you see.

Imminent violence. That’s what flat track is all about. Lions vs. Christians. Risk in a safe world.

Men crave risk. Women thrill at it, even if they don’t admit it. It’s all part of our primitive psyche. An emotional hangover from a world that we never knew, a world that was continually dangerous, a very human world. That world, though gone, resides in our primitive brain.

Even the riders get emotional about flat track. They create tight cliques and coteries. They create cults. The tuner cults of Axtell, Sifton, Macias, Branch, Warren, Berndt, O’Brien, Neas, Denzer, Guild, Demay, etc. The handling cults of Keen, Hensley, Mann, Lawwill, Kasten, Watkins, etc. Most of these people are quite straight, dress straight, have normal, everyday things to worry about, but somehow acquire the aspect of a witch doctor. As every witch doctor knows, the aura of mystery is created and preserved by not readily holding forth all your secrets. Some keep their secrets because they are not too articulate anyway. Otherslike Neil Keen, C.R. Axtell and Dick O’Brien—are more clever, and explain their secrets in pataphysical metaphor so that everybody nods, thinking they understand, having learned nothing, and tripping out reverently on the thought that one of these great dudes has laid some secret information on them.

The riders themselves get quite emotional. Gary Nixon flares his nostrils more at a good flat track race than he does at a road race.

Bart Markel never acted studious at Daytona, but he does at San Jose.

Eddie Mulder, the TT ace who doesn’t think he’s a good flat track rider, goes around the pits joking with comic big eyes that he scared himself.

Dick Mann, a model version of the lone wolf, is on the ultimate loneliness trip at a challenging flat track meet, a leathered, helmeted version of Rodin’s “Thinker.” And the lesser riders leave their steel skid shoes on between races and clomp around the pits looking bad ass, a racer’s parody of a skulking band of pachukos smoking across the street from the high school. A good flat track rider is by definition an uptight person. His nerves are tightly strung, and short fused. This is because the races are short, compared to other motorcycle sports, and he must pace his mind and body to brief, savage, man-to-man competition. If he is not on an ego trip, he has to put himself on one.

This is to make himself think that he is better in the saddle than anyone else, and make himself believe that what he is doing is worthwhile -worth enough in money and ego satisfaction to brave the risk inherent in throwing his motorcycle and himself sideways into a turn at 80 to 100 mph in the close and intent company of an odd dozen other guys on the same ferocious trip. It is not that this is so different from other motor sports, but that it occurs in such volcanic proportion.

The women involved on the periphery of flat track racing are strung just as tight. The casual ones, two or three chicks who would never be seen walking alone into a bar, brave the stands to pick up on what’s happening and rush through the gates after the final event to mingle in the pits, soak in the racers and . . . que sera.

The regularswives, mothers, girl friends -are so excitable on race night that you wouldn’t believe their actions if you had known them only in the daytime. They echo verbally and emotionally that which is happening physically on the business side of the crash fence. They banter, argue, make cutting remarks. They dress sharp and do their hair, vie with one another, sometimes not too subtly. And they cheer their men.

The head cheerleader in my realm of experience is a petite, gracious, conservative lady named Donna Rockwood, wife of Roxy, Golden Throat of the National Trail, and mother of Tommy.

Tommy’s out there. National No. 9. Donna’s up there, glowing in the light of the timing tower, wherein looms Roxy over his mike. I am sitting in front of Donna. The vibes I’m getting from these charged-up ladies in the special section are far heavier than anything 1 ever got from lurking in the pits, and that’s way too heavy for a motorcycle journalist who is obligated to retain a certain amount of professional dispassion. But I have a date with another soulful lady who knows more about flat track than I ever will, so I figure I'll learn something.

The race starts and I immediately begin learning. Donna Rockwood reaches down and grabs my arm with the force of a pipe cutter. Four thousand people, including myself and Donna, jump up to see if the main event is going to survive the first left turn. But she won’t let go of my arm.

Roxy announces that Tommy is leading through the first turn, but I can’t make out what he’s saying after that because Donna is jumping up and down and screaming:

Flatlrack

“C’mon Tommy oh Tommy yes Tommy oh Tommy! (he extends lead on back straight) cuuuuuummmmonnnn Tommy, do it Tommy (Lacher gets a better drive off Turn 4 and threatens Tommy) keep it down Tommy that’s it Tommy, yes. Tommy, keep it down, keep it down, that’s it, that’s it Tommmmmmmmmmy oh!”

My arm hurts and there are 14 laps to go, but if Donna Rockwood wants to hold on to my arm for 1 5 laps that’s okay, because I’ve already decided that 1 love her dearly.

Tommy won that race. Or maybe Donna won it. I’m not sure, because my values have been shaken and I’m seeing flat track for the first time as a grandstand player with vested interest and I’m confused by all this emotional input.

Back to the pits . . .

PART II: DOWN TO TERMS

FLAT TRACK RACING'S detrac tors generally support their put downs with the statement that: "All they are doing is turning left.” To be kind, these detractors are probably uninitiated and haven’t seen more than a few flat track races. To be cruel, they are somewhat ignorant.

And they don’t even have enough power of observation to figure out why you hang a Sears-Roebuck catalog inside the door of an outside john, nor why it’s a good thing that Sears doesn’t print their catalog on slick paper. Furthermore, they probably don’t have any soul, and they probably haven’t ever ridden a motorcycle in the dirt.

Turning left fast in the gritty slippery stuff, sparks flying from your steel skid shoe, has its inherent problems. It is visceral to be sure, half wrestling and half roller derby.

It is noisy, dirty and crude. But it is also tactical and requires brain as well as bravado. It is subtle, even. Mechanically, it has everything that road racing has. A well-tuned engine, suitable to the dual requirements of high peak horsepower (50 to 65) bhp and a power curve broad enough to shoot you out of the turn onto the straightaway like a rocket and have enough rpm left at midstraight to make you pucker in your seat.

Special steel alloy frames, a variety of spring/damper/fork settings to ferret out in practice, and difficult problems of tire size and tread pattern to suit the consistency of the dirt surface on a particular track on a particular day at a particular time of day.

Strategically, flat-track racing has much to offer the observant spectator, who has a chance to see the whole thing unfold from his handy perch in' the grandstand.

The most important concept is the “drive” a rider gets coming out of a

corner. Not only must a rider go through the actual corner as fast as traction and sang-froid will permit, but he must “set up” his machine (in terms of attitude, position in the turn, etc.) to provide the fastest possible exit, which boosts his acceleration up the straight.

Another useful concept is “the groove.” This is similar to “the line” in road racing, except that the line is usually a geometric constant representing the fastest path through a turn or series of turns. The groove tends to be variable, according to track condition, as well as the individual rider, his machine and its power and handling characteristics.

For some riders, the groove runs close to the inside of a turn. If the bike is extremely powerful in the mid-rpm range, a groove 10 or 20 ft. out may be more appropriate. Although the bike has farther to go through the turn, the improved bite (traction) in mid-track and the faster speed possible there may significantly overcome the extra distance to be traveled, particularly in respect to the drive onto the straight.

Track conditions may vary the groove a rider chooses. Some tracks are hard and slick and develop a “groove” or “blue groove” after the riders practice. Such tracks are called “groove tracks.” The groove, which may be marked by bluish-black deposits of rubber, tapers cautiously from the outside of the straight to a 5-to-l0-ft.-wide strip along the inside of the turn. Traction on a blue groove is marginal. Off the groove, traction is atrocious. Passing attempts may cause the rider to slip off the groove. So the race degenerates into a single-column freight train after a madcap dash to be first into Turn 1. Riders tend to “road race” a blue groove, keeping the bike fairly straight and steering it through the turns, rather than broadsliding it. Only a clever groove track specialist like Jim Rice, AMA National No. 2, can pass at will on a blue-groove half mile: he does it by careful manipulation of the variables: higher than normal gearing, careful attention to tires, “setting” the bike as he enters the turn, and oh-so-subtle application of the throttle through the turn and out.

At the other extreme is the “cushion” track, which affords traction and maneuverability at almost any distance from the apexes. A cushion track is just that—it has a cushiony coating of half-loose loam, clay or sandy base compound, into which a tire of proper tread pattern cuts beautifully and holds. A cushion track offers an infinite variety of grooves to the inventive rider, who may find that the fastest way around is a banzai, sideways charge through the very outside of the turns. This is known as riding a “high groove.”

Opportunity for passing strategy is at its greatest on a cushion track, which may have such an equalizing effect on the various power outputs of competing machines that several good riders may find themselves together

for the entire race, repeatedly swapping the lead, trying to outsmart the other rider, and often, with great frustration, waiting for the leader to make a mistake.

One tactic, applicable to a variety of tracks, but most common on the cushion track, is the act of “squaring off.” Given a leader who is adhering to a good groove, one which is hard for the man chasing him to improve, the act of squaring off may help the second man to pass the leader.

Squaring off consists of running into the turn wider than usual, turning the bike abruptly before passing the apex, and then cutting across the inside of the exit to slip underneath the leader, who is committed to a wider line at the exit.

Bart Markel is an absolute genius at squaring a turn, utilizing the brute horsepower and Gibraltar-like handling qualities of his HarleyDavidson in a fantastic display of violent acrobatics. He swoops into a turn, looking like he is going straight for the crash wall. Then, at the very last second, with the bike laid over, spewing a great rooster tail of dirt, he seems to stop dead and then spring back to the inside of the exit in a great, sputtering, roaring leap.

In effect, he has lengthened the next straightaway by 200 or 300 ft., with a corresponding gain in speed.

To the uninitiated, it looks like he passed the leader on the straight, while, in truth, he set up the pass by squaring off in turn, interrupting the other rider’s line and improving his own drive up the straight.

PART III: McCLUHANISM AND FLAT TRACK

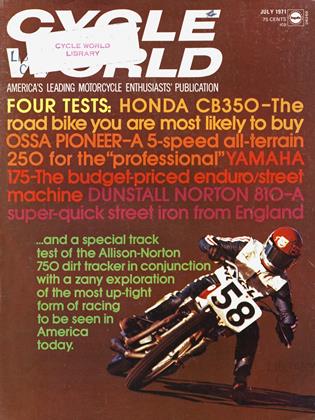

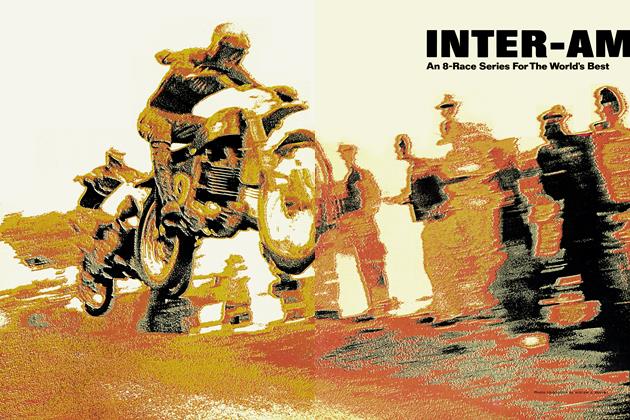

WHETI-IER THE SETTING be on the ubiquitous half-mile dirt tracks or the superfast mile tracks like Nazareth and Sacramento, where speeds approach 120 mph, flat track is inherently a good show because of its presentation.

Flat track is typically American, a stadium show laid out in front of you, no part of which escapes the eye. While it has lost the limelight somewhat as the world of American motorcycling has broadened and the factories throw money into bigtime road racing, there is a good case for arguing that flat track has greater potential in America than any of the motorcycle sports against which it is now competing.

One reason has to do with its psychological appeal to the post-war generation, the young people who are now turning on to motorcycling and are just beginning to fill the stands.

This is the TV generation, educated and accustomed to spectacles which offer lots of different action all at once. This is opposed to the Baseball Generation, accustomed to things happening one at a time.

The idea is not mine, it’s Marshall McCluhan’s. He’s the “Media Is The Message” man, the one who formulated Duke Ellington’s statement, “It ain’t what you do, it’s how you do it,” into a scientific scheme for looking at

people and how they interact, and react, in an increasingly technological age.

McCluhan feels that the one-thingat-a-time sports, like baseball, will give way in time to sports ottering a simultaneity of actionlike football or basketball. To the TV Generation, baseball is easy to watch. But it is also a dead bore to some because it plods along, one pitch at a time.

Football or basketball, by comparison, is an absolute mess to watch. Players run heiter skelter everywhere. The old generation, the Baseball people with their scorecards and r.b.i. sheets, can’t dig it. Helter-skelter sports are too confusing; they aren’t linear and ordered in time. But the non-linear young people, used to multi-media freak shows, Cubism and television’s disjointed, bouncing, scene-to-scene logic, can handle football and basketball quite well.

Comparing motorcycle sports in the light of McCluhanism, several parallels begin to occur. Both motocross and road racing emerge as relatively linear sports. The reason that they are linear has to do with their presentation. They are usually on large courses. You can’t see all the action at once. After a zingy few opening laps, the field thins out, and becomes a one-by-one parade. Only the statisticians, with their lap charts and stop watches, are having a hey day.

The Young Non-Linears, on the other hand, are getting bored. They retreat to their ice chests and flake out on the hill. What the hell, the day is nice and the beer is good. If they are lucky, they’ll find out what happened in a Non-Linear magazine or newspaper devoted to the sport.

Contrast this to flat track. The crowd is jumping all the way from qualifying to the last lap of the main event.

In between they see six heat races, a semi and two main events -if it is a National—or even more, if it is a local race.

One race right after another, one crisis following another, multiple, direct and simultaneous conflict.

And in spite of the moldy, often corny way in which it is presented (flat track could streamline itself beautifully by borrowing from the brisker speedway format),flat track suits the TV baby in almost every way. If his mind wanders, there will always be another race in a few minutes, and he can get straight with what’s happening.

It doesn’t matter when he tunes in.

Flat track is one of the finest motor sports available to the American today, and, indeed, it is one of the few that cannot be improved by editing through the media of television coverage.

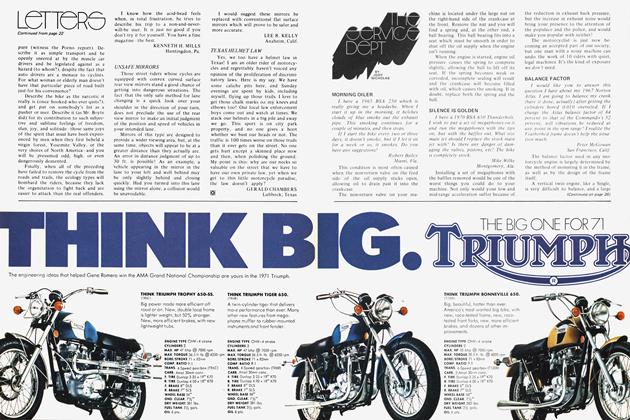

Perhaps one day it will receive the high-powered promotion that it deserves.