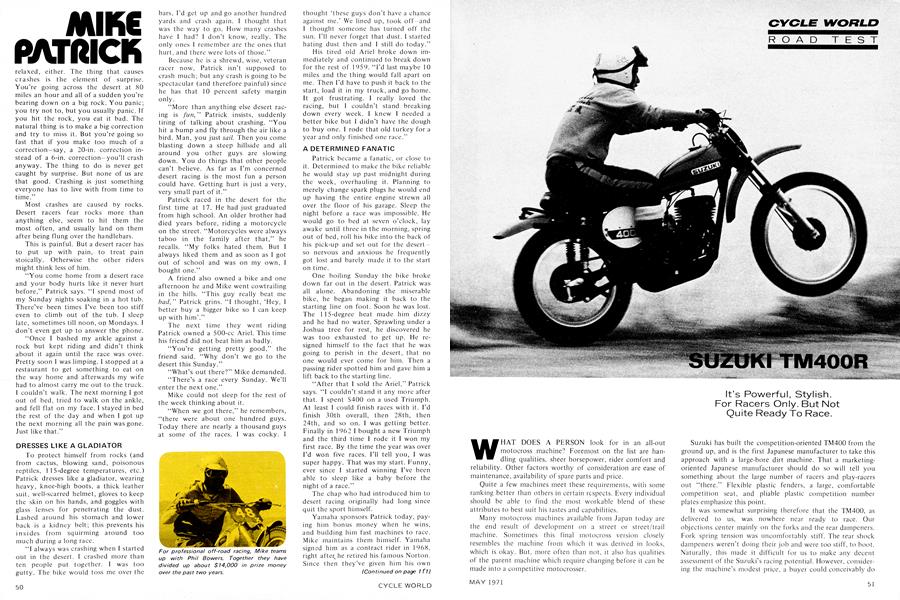

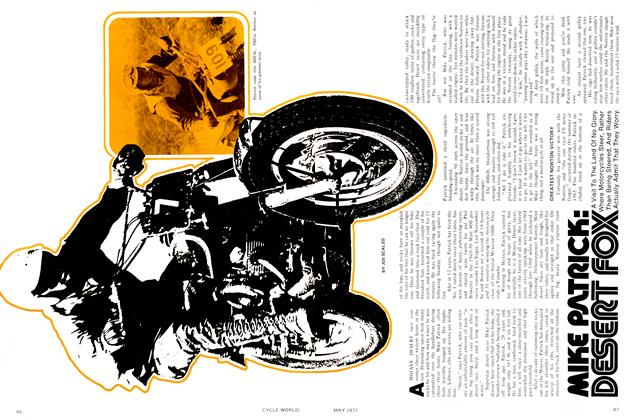

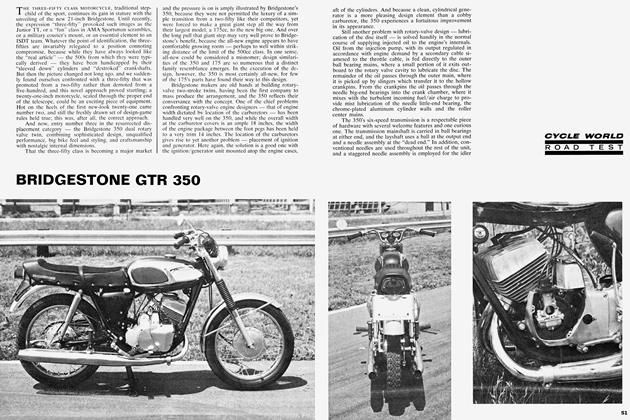

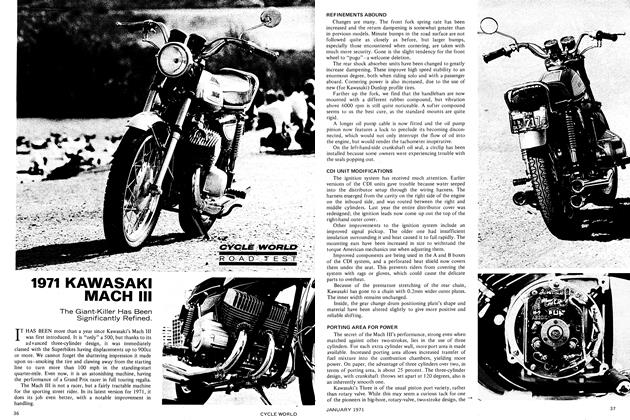

SUZUKI TM400R

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

It’s Powerful, Stylish. For Racers Only. But Not Quite Ready To Race.

WHAT DOES A PERSON look for in an all-out motocross machine? Foremost on the list are handling qualities, sheer horsepower, rider comfort and reliability. Other factors worthy of consideration are ease of maintenance, availability of spare parts and price.

Quite a few machines meet these requirements, with some ranking better than others in certain respects. Every individual should be able to find the most workable blend of these attributes to best suit his lastes and capabilities.

Many motocross machines available from Japan today are the end result of development on a street or street/trail machine. Sometimes this final motocross version closely resembles the machine from which it was derived in looks, which is okay. But, more often than not, it also has qualities of the parent machine which require changing before it can be made into a competitive motocrosser.

Suzuki has built the competition-oriented TM400 from the ground up, and is the first Japanese manufacturer to take this approach with a large-bore dirt machine. That a marketingoriented Japanese manufacturer should do so will tell you something about the large number of racers and play-racers out “there.” Flexible plastic fenders, a large, comfortable competition scat, and pliable plastic competition number plates emphasize this point.

It was somewhat surprising therefore that the TM400, as delivered to us, was nowhere near ready to race. Our objections center mainly on the forks and the rear dampeners. Fork spring tension was uncomfortably stiff. The rear shock dampeners weren’t doing their job and were too stiff, to boot. Naturally, this made it difficult for us to make any decent assessment of the Suzuki’s racing potential. However, considering the machine’s modest price, a buyer could conceivably do

some simple fork tuning, buy a set of proper rear springs and dampeners, and still come out ahead in total investment. On the positive side, the TM400 is one of the most powerful big-bore, two-stroke Singles we have tested, and its presentation for the most part is impeccable.

Typical Suzuki quality is evident from the outside of the engine/transmission unit. Smooth, alloy castings are finished in matt black to help dissipate heat. Large, widely spaced finning

on the cylinder and cylinder head helps cooling too.

Another spark plug hole is tapped adjacent to the primary hole, but most people will probably elect to fit a compression release. With the primary gear kickstarter, which makes it possible to start the engine in any gear as longas the clutch is disengaged, cranking the big two-stroke is, at best, a chore. A compression release would allow the rider to get the piston past compression and the crankshaft in motion to carry it

through to the next compression stroke.

A huge 82.5-mm diameter piston rides on needle bearings and features two Dykes-type rings with locating pins to keep them from rotating in their grooves. This is extremely important on the TM400, as there are no bridges in the enormous intake or exhaust ports. Four smaller transfer ports move the fucl/air mixture from the crankcase into the cylinder.

The beefy connecting rod assembly rides on caged roller bearings and is of the classic I-beam shape, which allows a narrow mean cross-section while retaining the strength necessary for its job.

“HALF-CIRCLE” FLYWHEELS

Most unusual is the flywheel assembly, which is ot the “half-circle” variety. Crankcase pressure is necessary in a two-stroke engine to get the fuel/air mixture from the crankcase up into the cylinder. So, “full-circle” flywheels are most often used. Suzuki has found that sufficient pressure is developed using the “half-circle” flywheel, which is heavy enough to smooth out the power impulses and help get the power to the ground. Large diameter ball bearings support the crankshaft.

A solid copper head gasket fits into a recess in the cylinder head, into which slides the cylinder’s deep spigot. Six 10-mm studs assure sealing the compression pressures inside the combustion chamber.

Many construction features and components have been borrowed from other members of Suzuki’s line. The clutch, driven from the engine by straight-cut gears for minimum power loss, is virtually identical to the T-500 Titan’s clutch. Seven neoprene driving plates and seven metal driven plates are forced together by six springs. A rather unusual worm gear disengaging mechanism reduces lever pressure considerably. Many small grooves in the inner clutch hub, which is aluminum along with the outer housing, help distribute more evenly the loading imposed by the plates. Directly to the rear of the clutch hub is the primary kickstarter gear, which also serves to drive the Teflon-like plastic oil pump gear.

POSITIVE LUBRICATION

Lubrication is identical to other models featuring the CCI-forced injection system. The variable displacement, pis-

ton-type oil pump is controlled both by engine rpm and throttle opening to provide the correct amount of lubrication under any circumstance. Oil from the pump is injected directly into the left main bearing and into the intake port to lubricate the connecting rod bearing, piston pin needle bearing and cylinder wall. Oil which first lubricated the left main bearing is discharged into the crankcase through a hole in the left transfer port, supplying additional oil to the rod bearings and cylinder wall. The right main bearing is lubricated by the transmission oil.

Also similar to other Suzuki models is the transmission and shifting arrangement. A drum-type shifter assembly is rotated by a spring-loaded pawl. Three short half-forks ride in grooves on the drum, reducing the friction generated by more conventional girdling shifting forks. The transmission’s gears are all very wide and the ones that aren’t integral with shafts ride on needle bearings. Shifting is light and crisp, aided in no small measure by careful design of the gears, their dogs and receivers.

Carburetion is handled by a 34-mm Mikuni, which features a “gas trap” around the main jet. This feature, developed by the factory for their racing machines, keeps the relative float level more constant when covering and negotiating jumps by keeping a supply of fuel in the main jet’s proximity. In fact, the engine will run for over two minutes at a fast idle while leaned over practically horizontal to the ground! Racing does improve the breed.

A shrouded, large-capacity, dry-paper air cleaner element keeps abrasive dirt and grit out of the engine.

STIFF SUSPENSION

The front suspension is very robust. A fork travel of some 7 in. wasn’t attainable because of that inordinately heavy spring rate. This fault was pointed out to the factory, and should be remedied by the time the first production batch of machines arrives.

Front end geometry is excellent, providing precise steering and good control. Despite its small diameter and width, the front brake is just right for motocross racing where high speeds aren’t the rule. Even under heavy braking, the forks didn’t deflect or twitch to one side.

The stiffness plagueing the rear suspension prevents us from making any comment about dampening. A typical symptom:

rear wheel chatter. The suspension consists of two single-rate springs of different poundage separated by a Teflon-like washer, allowing 4 in. of travel. This approach differs from the conventional one of using a single, progressively wound spring. But it must work. The same type of springing is used on the RH-70 “works” motocross machine.

Following traditional motocross practice, the single downtube cradle frame’s main tube splits into two smaller diameter tubes below the front of the engine. These tubes continue rearward, bending upward behind the engine and terminating in the rear suspension’s top mounts. Another loop is formed by a tube which joins the two tubes just mentioned and extends rearward. This loop provides a mounting place for the rear fender and supports the seat.

Thick gussets extending from the downtube to the steering head, and then to the toptube, assure rigidity in that critical area. Similar gusseting is employed to mount the engine and to support the rear wheel in the swinging arm. Large diameter tubing forms the swinging arm which rides on hefty bushings and appears immune to flexing, a quality necessary on a highly stressed motocross machine.

Rider comfort is very good indeed. The relationship between the seat, footrests and handlebars is just as it should be for motocross racing, and the extra long seat gives the rider a great variety of seating positions. Handling is very neutral, and the engine has so much power that lofting the front wheel was an easy matter.

The transmission's five closely spaced ratios made the “pipey” power characteristics easier to live with. Opening the throttle wide in almost any gear brought on a great, hairy rush of power. It takes a good rider to be able to control this power to the fullest, but once the technique is mastered, the TM400 could be a winner.

POINTLESS IGNITION

Of special note is the new pointless electronic ignition (PEI) manufactured for Suzuki by Kokusan Denki, Ltd. It consists of a conventional rotor on the left end of the crankshaft which revolves between a stator plate containing two coils. The current produced by the magnet moving past the exciter coil charges one condenser with 200-300 volts which is held by an electronic “gate.” The magnet then sweeps past the signal coil that triggers the SCR (silicon controlled rectifier) which acts as the points.

An automatic spark advance curve is provided by the increase in voltage at higher rpm. giving the machine a range of from 8 degrees advance at approximately 2000 rpm to about 28 degrees total advance at 5000 rpm. All the triggering and rectifying functions are performed within the “magic black box” under the seat. Once set, the timing will not vary until, 1 ) the engine has to be dismantled, or 2) the components within the “black box” change their operating characteristics due to age. The simplicity of the entire system makes it ideal for competition use.

We’d like to see U.S. Suzuki make a “trail kit” available as an option. Such a kit would contain another cylinder with

milder port timing, a lower compression cylinder head and possibly a muffling system to fit on the end of the exhaust pipe's stinger. Even with the kit installed, there would be more power available than most riders could use properly for motocross racing.

The TM400 scores in both beauty and utility, as exemplified by the gas tank shape, the folding footpegs that provided excellent grip while standing up. and the overall quality of the paintwork and finish in general.

The TM400R is one of the most admirable efforts of a large factory in recent years. And the suggested list price of $999, lower by a few hundred dollars than some of the machines with which it will have to contend, makes it tempting for the serious racer.

SUZUKI TM400R

$999