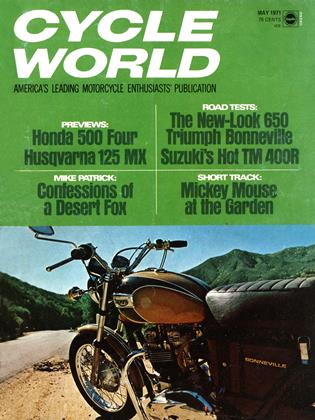

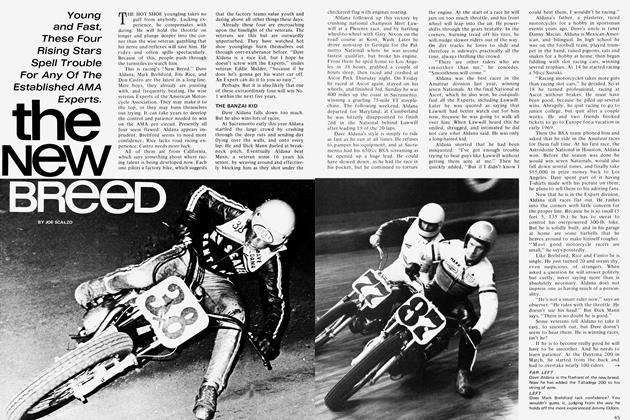

MIKE PATRICK: DESERT FOX

JOE SCALZO

A Visit To The Land Of No Glory, Where Motorcycles Steer, Rather Than Being Steered, And Riders Actually Admit That They Worry.

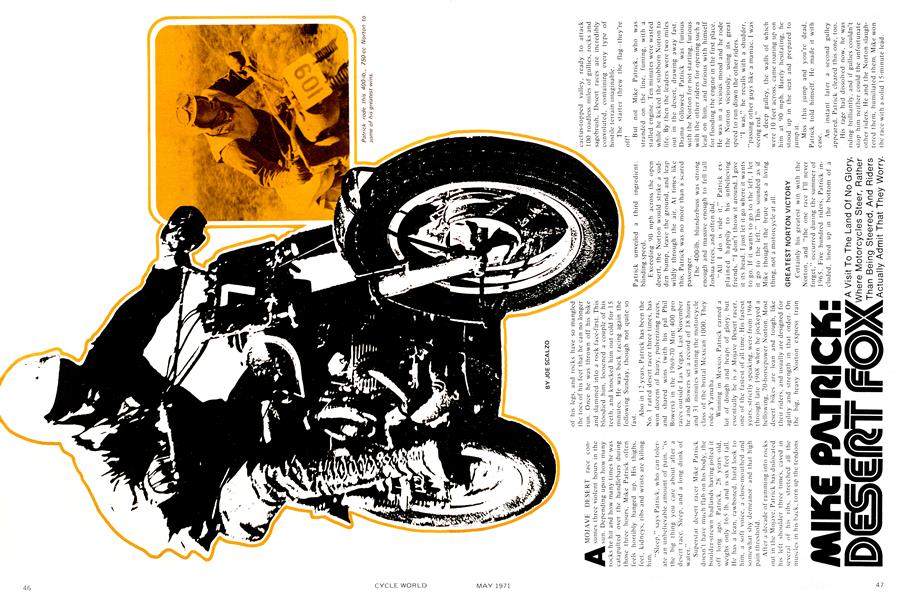

A MOJAVE DESERT race consumes three violent hours in the sun. Depending upon how many rocks he hit and how many times he was catapulted over the handlebars during those three hours, Mike Patrick often feels horribly banged up. His thighs, feet, kidneys, ribs and wrists are killing him.

S1t~~p~" says Patrick, who can toler ate an unbelievable amount of pain, ``is the big thing you care about after a desert race. Sleep, and a long drink of water."

Superstar desert racer Mike Patrick doesnt have much flab on his body, the boulder-st rewn bad lands having jolted it ff long ago. Patrick. 28 years old. weighs only 1 65 lb. and is six feet tall. lie has a lean, rawboned, hard look to him, a sott voice, a close-mou t lied and soniewhat shy den~eanor-•and that high pain threshold. After a decade of ramming into rocks out in t he \1 ojave. Pat rick has dislocated his left shoulder three times, caved in several of his ribs, stretched all the muscles in his back, torn up the tendons

of his legs, and rocks have so mangled~ the toes of his feet that he can no longer run. Once he was thrown off his bike and slammed into a rock face-first. This bloodied him, loosened a couple of his teeth, and knocked him out cold for 15 minutes. He was back racing again the following Sunday, though not quite so fast. Also in 1 2 years, Patrick has been the No. I rated desert racer three times, has won dozens of hairy, pulverizing races, and shared wins (with his pal Phil Bowers) in the 1969-70 Mint 400 pro races outside Las Vegas. Last November he and Bowers set a record of 1 hours and 31 minutes winning the motorcycle class of the brutal Mexican 1000. They rode a Yamaha. Winning in lot of dough essentially he Mexico, Patrick earned a and heaps of glory, hut is a Mojave Desert racer, one of the fastest of all time. His fastest years. strictly speaking, were from 1 964 through late 1968 when he jockeyed a bellowing, 70-horsepower Norton. Most desert bikes are lean and tough, like their riders. and usually are designed for agility and si rength in that order. On the big. heavy Norton express train

Patrick unveiled a third ingredient: blinding speed. Exceeding 90 mph across the open desert, the Norton would strike a sud den hump, leave the ground, and leap wildly through the air. At times like this, Patrick was no more than a seared passenger. The 400-lb. blunderbuss was strong enough and massive enough to fell tall Joshua trees, and often did. "All I do is ride it," Patrick ex plained happily to his unbelieving friends. "I don't throw it around. I give it its head. I just let it go where it wants to go. If it wants to go to the left. I let it go to the left." This sounded as if Mike thought the brute was a living thing, not a motorcycle at all. GREATEST NORTON VICTORY Certainly his greatest win with the Norton, and "the one race I'll never forget." occurred during the summer of 1965. Five hundred riders, Patrick in cluded, lined up in the bottom of a

cactus-topped valley, ready to attack 1 00 roadless miles of gullies, rocks and sagebrush. Desert races are incredibly convoluted, containing every type of hostile terrain imaginable. The starter threw the flag--they're off! But not Mike Patrick, who was stranded on the line, fuming, with a stalled engine. Ten minutes were wasted while he kicked the stubborn Norton to life. By then the leaders were two miles out in the desert, drawing away fast. l)rama followed. Patrick was furious with the Norton for not starting, furious with the other riders for opening such a lead on him, and furious with himself for flooding the engine in the first place. He was in a vicious mood and he rode the Norton viciously, using its great speed to run down the other riders. "I was," he recalls with a shudder, "passing other guys like a maniac. I was seeing red." A deep gulley, the walls of which were 1 0 feet across, came roaring up on him at 90 mph. Barely hesitating, he stood up in the seat and prepared to jump it. Miss this jump and you're dead, Patrick told himself. He made it with ease. An instant later a second gulley appeared. Patrick cleared this one, too. His rage had dissolved now, he was riding brilliantly, and if gullies couldn't stop him neither could the unfortunate other riders. He and the Norton slaugh tered them, humiliated them. Mike won the race with a solid I 5-minute lead.

Phenomenal feats like Patrick's 1 0-ft. guile V j urn p5 (lout happen often in the desert, hut they happen more than you would think. Not surprisingly, Patrick was reluctant to talk al)out the gullies at terwards. No one believes a fish story. Desert racing is a highly personal sport and in many ways a lonely one: no photogra phers were crouching in t lie rocks shooting pictures of Patrick's fantast ic leaps. No spectators were around to a P p Ia u d Patrick claims he doesn't really care about applause or cheap glory, that the tremendous personal sat isfact ion lie de rives from conquering t lie desert each Sunday is enough. To (it her riders it isn't. The great FT Steeplechase cham pion Skip Van Leeuwen says one reason lie doesn't race in the \lojave is because lie loves glory. "When 1 (10 soiiiet hing spectacular on a hike,'' Van Lceuwen says, "I want people to be there to see it, to remember it. I like the sound of applause. LITTLE APPLAUSE, NO MONEY A ppla use is soniet ii ing a desert racer hears rarely.

No prize money is offered, none asked for. The American NI otorcycie Association designates desert races as ``sportsman' aff'airs. The lack of dough is another thing keeping away profes sionais like Van Leeuwen and Dick Mann (Who nevertheless says he would enjoy this type of racing proba hly most of all). One of the few pros moonlight ing as a (lesert racer is the versatile l)usty (`oppage. Even if he raced for cash it is hard to believe that Patrick could attack the desert any harder than he l()es' air eady. Patrick treats every desert race as if it were, say, The Daytona 200. He suffers hrough each one. After all this t iine he still picks at his bacon and eggs on Sunday mornings and somet inies can't keep l)reakfast down at all. A bundle of nerves before a race, he resists conversa (ion and clia in-smokes, All the while he stares balefully out at the jagged desert floor, the enemy. Sometimes Mike mumbles a prayer before hoarding his hike at the start. The start is the most dangerous moment of any desert race: a mob of riders drop clutches and go blasting through I lie sagebrush at terrific speed. lerrihle pile-ups have occurred, involv ing dozens of riders. In thick dust, one rider unavoidahly bashes into a not her and others careen helplessly iiito the wreckage. It annoys Patrick that lie can't force himself to plunge through the (lust very

fast. I-Ic always holds his hike in reserve a little. But he knows that once the dust thins he will be able to ride down those who got the jump on him, circum venting their bravery with his skill. 1 don't mind a tough race,'' he says, `a race where you're d ueling with another guy for the lull t hree hours. But what I don't enjoy is if the guy I'm dueling with is just a little faster than I am on that particular day. ``All of us have days when we're fast, other (lays when we're not quite as fast. If the guy I'm dueling with has a slight edge on me, if he's a little faster than I am, if I really have to stick my neck out a mile to keep up with him, well, that's very unenjoyahle for me." Desert racing is phenomenally popu lar in Southern (`alifornia, even though the sport gets little publicity, and there are better than 3000 licensed riders. Those frequently making racing unen joyable to Patrick include the vet era ii [.arry Berquist , young Toni Poteet, and iN. (Jimmy Roberts), a tough little stuntman in the iiio~ies when he isn't racing. Pa trick hat ties wit Ii these guys every Sunday but doesni know any of them very well. ``We (lont talk much before the start because we're all SO nervous,' he cx plains, ``a tid after a race is over we don't talk cit lie r. We're too worn out from racing with each other.'' Probably Patrick is too shy and niodest for his own good. "I don't think

I `iii talented,'' he has said, doggedly. Few desert racers are as outspoken and sell-confident as a professional like Van Leeuwen, probably because they never get much publicity and attention lav ished upon them and therefore don't take themselves too seriously. that Pat rick doesn't think of himself as being talented is revealing -and startling. Act ually, he is a virtuoso. 1-fe had better be. To stay on two wheels while bouncing h rough gullies, broadsl idi ng over the top of deep sand, and rocket irig UP the sides of rocky foothills is an art. It also takes guts. An average race covers 100 miles. A hack rider would fall a (10/en times in the first mile. Patrick concedes: `~All the riders know the desert pretty well. From the color of the ground we can tell where rocks are coming up ahead, or we can tell from the way the bushes lay. The more you race, the more you know when to start slowing down and when to really go. But you can't explain that to anybody. It's something you learn from racing every Sunday, all year.'' Also: "We race with a 10-percent safety margin. i\ll of us could go 10 percent faster, if we had to, but not for long. Sometimes, depending on who youre racing with, you have to. That's bad news. "It's complicated. You can't ride tense. holding the handlebars in a death grip all day long. But you can't ride too

relaxed, either. I he thing that causes crashes is the element of surprise. You’re going across the desert at 80 miles an hour and all of a sudden you’re bearing down on a big rock. You panic; you try not to, but you usually panic. If you hit the rock, you eat it bad. The natural thing is to make a big correction and try to miss it. But you’re going so fast that if you make too much of a correction—say, a 20-in. correction instead of a 6-in. correction-you’ll crash anyway. The thing to do is never get caught by surprise. But none of us are that good. Crashing is just something everyone has to live with from time to time.”

Most crashes are caused by rocks. Desert racers fear rocks more than anything else, seem to hit them the most often, and usually land on them after being flung over the handlebars.

This is painful. But a desert racer has to put up with pain, to treat pain stoically. Otherwise the other riders might think less of him.

“You come home from a desert race and your body hurts like it never hurt before,” Patrick says. “I spend most of my Sunday nights soaking in a hot tub. There’ve been times I’ve been too stiff even to climb out of the tub. I sleep late, sometimes till noon, on Mondays. I don’t even get up to answer the phone.

“Once I bashed my ankle against a rock but kept riding and didn’t think about it again until the race was over. Pretty soon 1 was limping. I stopped at a restaurant to get something to eat on the way home and afterwards my wife had to almost carry me out to the truck. I couldn’t walk. The next morning I got out of bed, tried to walk on the ankle, and fell flat on my face. I stayed in bed the rest of the day and when I got up the next morning all the pain was gone. Just like that.”

DRESSES LIKE A GLADIATOR

To protect himself from rocks (and from cactus, blowing sand, poisonous reptiles, 115-degree temperatures, etc.) Patrick dresses like a gladiator, wearing heavy, knee-high boots, a thick leather suit, well-scarred helmet, gloves to keep the skin on his hands, and goggles with glass lenses for penetrating the dust. Lashed around his stomach and lower back is a kidney belt; this prevents his insides from squirming around too much during a long race.

“1 always was crashing when I started out in the desert. I crashed more than ten people put together. I was too gutty. The bike would toss me over the

bars, I’d get up and go another hundred yards and crash again. I thought that was the way to go. How many crashes have I had? I don’t know, really. The only ones 1 remember are the ones that hurt, and there were lots of those.”

Because he is a shrewd, wise, veteran racer now, Patrick isn’t supposed to crash much; but any crash is going to be spectacular (and therefore painful) since he has that 10 percent safety margin only.

“More than anything else desert racing is fun,” Patrick insists, suddenly tiring of talking about crashing. “You hit a bump and fly through the air like a bird. Man, you just sail. Then you come blasting down a steep hillside and all around you other guys are slowing down. You do things that other people can’t believe. As far as I’m concerned desert racing is the most fun a person could have. Getting hurt is just a very, very small part of it.”

Patrick raced in the desert for the first time at 17. He had just graduated from high school. An older brother had died years before, riding a motorcycle on the street. “Motorcycles were always taboo in the family after that,” he recalls. “My folks hated them. But I always liked them and as soon as I got out of school and was on my own, I bought one.”

A friend also owned a bike and one afternoon he and Mike went cowtrailing in the hills. “This guy really beat me bad,” Patrick grins. “I thought, ‘Hey, I better buy a bigger bike so I can keep up with him’.”

The next time they went riding Patrick owned a 500-cc Ariel. This time his friend did not beat him as badly.

“You’re getting pretty good,” the friend said. “Why don’t we go to the desert this Sunday.”

“What’s out there?” Mike demanded. “There’s a race every Sunday. We’ll enter the next one.”

Mike could not sleep for the rest of the week thinking about it.

“When we got there,” he remembers, “there were about one hundred guys. Today there are nearly a thousand guys at some of the races. I was cocky. I

thought ‘these guys don't have a chance against me.’ We lined up, took off—and I thought someone has turned off the sun. I’ll never forget that dust. I started hating dust then and I still do today.”

His tired old Ariel broke down immediately and continued to break down for the rest of 1959. “I’d last maybe 10 miles and the thing would fall apart on me. Then I’d have to push it back to the start, load it in my truck, and go home. It got frustrating. I really loved the racing, but I couldn’t stand breaking down every week. I knew I needed a better bike but I didn’t have the dough to buy one. I rode that old turkey for a year and only finished one race.”

A DETERMINED FANATIC

Patrick became a fanatic, or close to it. Determined to make the bike reliable he would stay up past midnight during the week, overhauling it. Planning to merely change spark plugs he would end up having the entire engine strewn all over the floor of his garage. Sleep the night before a race was impossible. He would go to bed at seven o’clock, lay awake until three in the morning, spring out of bed, roll his bike into the back of his pick-up and set out for the desert — so nervous and anxious he frequently got lost and barely made it to the start on time.

One boiling Sunday the bike broke down far out in the desert. Patrick was all alone. Abandoning the miserable bike, he began making it back to the starting line on foot. Soon he was lost. The 115-degree heat made him dizzy and he had no water. Sprawling under a Joshua tree for rest, he discovered he was too exhausted to get up. He resigned himself to the fact that he was going to perish in the desert, that no one would ever come for him. Then a passing rider spotted him and gave him a lift back to the starting line.

“After that I sold the Ariel,” Patrick says. “I couldn’t stand it any more after that. I spent $400 on a used Triumph. At least I could finish races with it. I’d finish 30th overall, then 28th, then 24th, and so on. I was getting better. Finally in 1962 I bought a new Triumph and the third time I rode it I won my first race. By the time the year was over I’d won five races. I’ll tell you, I was super happy. That was my start. Funny, ever since I started winning I’ve been able to sleep like a baby before the night of a race.”

The chap who had introduced him to desert racing originally had long since quit the sport himself.

Yamaha sponsors Patrick today, paying him bonus money when he wins, and building him fast machines to race. Mike maintains them himself. Yamaha signed him as a contract rider in 1968, right after; he retired his famous Norton. Since then they’ve given him his own

(Continued on page 111)

Continued from page 50

dealership in Corona, a 90-minute drive from Los Angeles, where he lives with his high school sweetheart Annett, two children (Don, 10, and Windy, 9), a female Belgian Shepherd, two black cats, and a pet turkey that ran away recently. Before getting his own place Mike worked as a mechanic in various area bike shops. His son Don can ride a full-sized motorcycle already. The boy plans to race in the desert someday, just like his old man.

But for all his racing in Southern California Patrick has seen a lot of the world. He has been to the Isle of Man and East Germany to compete in the International Six Day Trials. Last summer Spain hosted the Trials and Patrick went over on sort of a vacation, taking Annett with him. Both of them became sick from eating the unfamiliar Spanish food, and the vacation cost Mike about $1600, but he figures it was worth it. (Annett puts up with her husband’s racing, often has to bandage him up when hè gets home, and during the week manages the books and works

behind the service counter at the shop. She doesn’t seem to mind that she and Mike have little time left over for an active social life. )

Patrick also has raced several times in the annual Jack Pine Enduro, gouging his way through the densely wooded hills of Michigan. The first year he equipped his bike with the long, wide handlebars he prefers for desert racing and succeeded in smashing his knuckles flat against trees. Trees are things a desert racer like Patrick sees seldom.

PRO OFF-ROAD DOMINATION

More recently Patrick and Phil Bowers, a racing school teacher, have been dominating professional off-road racing. In little more than two years they’ve split up about $14.000 in prizes between them. Patrick rode against the orders of his doctor in the recent Mexican 1000 (he’d spilled at a Mojave race the week before and sprained his back), then his bike ran out of gas a couple of miles from the finish on the outskirts of La Paz. Borrowing a gallon from some spectators by the side of the road, he still roared into La Paz with a 9-min. lead. Bowers rode the first 500 miles from Ensenada to El Arco, where Patrick relieved him. Waiting for Bowers to arrive. Mike’s sore back was bothering him so much he didn’t know if lie could ride or not. He proceeded toward

(Continued on page 116)

Continued from page 111

La Paz. with great caution and restraint. Every bump in the road sent tremors of pain through his entire body.

This one race got Patrick more publicity than all his Mojave racing put together, and loosened his tongue to the extent where he gave some talks about desert racing recently, mostly at high schools, for his Yamaha sponsors. Still modest, he worries that he is getting too much credit for winning and his partner Bowers not enough. Bowers also is unusually shy and close-mouthed. “Phil Bowers is just as fast a rider as 1 am," Mike says, and means it.

Patrick carried part of his Mexican winnings to Las Vegas. Gambling is one of the few luxuries he allows himself, and he proceeded to take $500 from the dice tables at the Mint Hotel in a single hour. He travels to Vegas a dozen or so times a year, but doesn’t always win, Patrick jokes about this often. He has a sense of humor, but you have to dig for it. Much of his humor takes the form of stories about desert races he has been in. Clearly, desert racing rules his life and is practically the only thing he is interested in. When Patrick isn't racing he is thinking about racing—an awesome single mindedness that all winners possess. He doesn’t have the hots to attempt any other type of racing, only the desert, although probably he has the talent (despite what he says) to excel at any kind of motorcycle racing he chooses. Recent moves to fence off the desert and restrict its usage trouble him because he doesn’t know how to fight the moves. Though he doesn’t talk about it much, he is quietly protective about his tough, winning reputation on the desert. “I don’t like to finish 2nd or 3rd,” he has said privately, “because that blows my image.”

Racing even creeps into his dreams at night. Mike once watched himself plummet off the wall of a sheer cliff. The next day in the desert the horrifying dream came true.

“I wasn’t hurt,” he says, smiling slightly, “but going off that cliff shook me up so much 1 wasn’t worth a damn for the rest of the race. It was exactly like 1 saw it in the dream. 1 was just pure lucky that the bike landed in soft sand.

“I had another dream once,” he continues, “and 1 hope it never comes true. 1 dreamed l rode a whole desert race with no front wheel-just doing a big wheclie from start to finish. That* I can do without.” [Ö]